<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Richard Courant, 1888

- Poet Francisco González Bocanegra, 1824

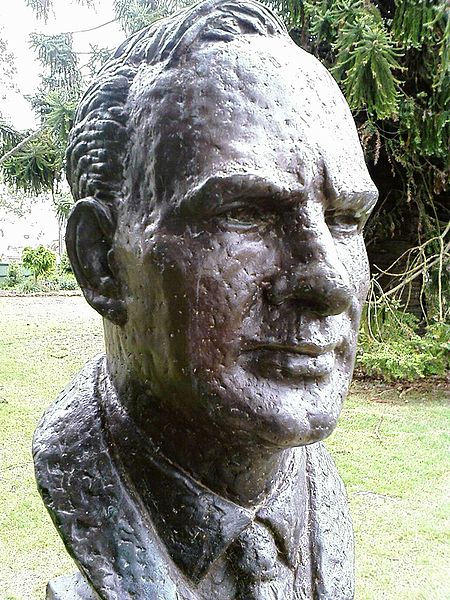

- 14th Prime Minister of Australia John Joseph Curtin, 1885

PAGE SPONSOR

John Joseph Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945), Australian politician and the 14th Prime Minister of Australia, led Australia when the Australian mainland came under direct military threat during the Japanese advance in World War II. He is widely regarded as one of the country's greatest Prime Ministers. General Douglas MacArthur said that Curtin was "one of the greatest of the wartime statesmen". His Prime Ministerial predecessor, Arthur Fadden of the Country Party wrote: "I do not care who knows it but in my opinion there was no greater figure in Australian public life in my lifetime than Curtin."

Curtin was born in Creswick in central Victoria. His name is sometimes shown as "John Joseph Ambrose Curtin". He chose the name "Ambrose" as a Catholic confirmation name at around age 14; this was never part of his legal name. He left the Catholic faith as a young man, and also dropped the "Ambrose" from his name. His father was a police officer of Irish descent; Curtin attended school until the age of 14 when he started working for a newspaper in Creswick. He soon became active in both the Australian Labor Party and the Victorian Socialist Party, a Marxist group. He wrote for radical and socialist newspapers as "Jack Curtin".

It is believed that Curtin's first bid for a public office was when he stood for the position of secretary of the Brunswick Australian rules football club, and was defeated. He had earlier played for Brunswick between 1903 and 1907.

From 1911 until 1915 Curtin was employed as secretary of the Timberworkers' Union, and during World War I he was a militant anti-conscriptionist. He was the Labor candidate for Balaclava in 1914. He was briefly imprisoned for refusing to attend a compulsory medical examination, even though he knew he would fail the exam due to his very poor eyesight. The strain of this period led him to drink heavily, a vice which blighted his career for many years. In 1917 he married Elsie Needham, the sister of Labor Senator Ted Needham.

Curtin moved to Cottesloe near Perth in 1917 to become an editor for the Westralian Worker, the official trade union newspaper. He enjoyed the less pressured life of Western Australia and his political views gradually moderated. He joined the Australian Journalists' Association in 1917 and was elected Western Australian President in 1920. He wore his AJA badge (WA membership #56) every day he was Prime Minister.

In

addition to his stance on labour rights, Curtin was also a strong

advocate for the rights of women and children. In 1927, the Federal Government convened a Royal Commission on Child Endowment Curtin was appointed as member of that commission. He stood for Parliament several times before winning the federal seat of Fremantle in 1928. He was expected to be chosen as a minister in James Scullin's Labor cabinet when it was formed after the 1929 election, but disapproval of his drinking kept him on the back bench. He lost his seat in 1931, but won it back in 1934. After the loss Curtin became the advocate for the Western Australian Government with the Commonwealth Grants Commission. When

Scullin resigned as Labor leader in 1935, Curtin was unexpectedly

elected (by just one vote) to succeed him. The left wing and trade

union group in the Caucus backed him because his better known rival, Frank Forde,

had supported the economic policies of the Scullin administration. This

group also made him promise to give up drinking, which he did. He made

little progress against Joseph Lyons' government (which was returned to office at the 1937 election by

a comfortable margin); but after Lyons' death in 1939, Labor's position

improved. Curtin fell only a few seats short of winning the 1940 election.

In that election, Curtin's own seat of Fremantle was in doubt; F.R Lee

appeared to have won the seat, and it was not until final counting of

preferential votes that Curtin knew he had won the seat. In

September 1939 the world plunged into war when Germany invaded Poland.

The Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies declared the country's

allegiance and support of the UK war effort. In 1941 Menzies travelled

to the UK to discuss Australia's role in the war strategy, and to

express concern at the reliability of Singapore's defences. While he

was in the UK, Menzies lost the support of his own party. Curtin had refused Robert Menzies'

offer to form a wartime "national government," partly because he feared

it would split the Labor Party, though he did agree to join the Advisory War Council. In October 1941, Arthur Coles and Alexander Wilson, the two independent MPs who had been keeping the conservatives (led first by Menzies, then by Arthur Fadden) in power since 1940, switched their support to Labor, and Curtin became Prime Minister. On 7 December 1941, the Pacific War broke

out. Curtin addressed the nation on the radio; "Men and women of

Australia. We are at war with Japan. This is the gravest hour of our

history. We Australians have imperishable traditions. We shall maintain

them. We shall vindicate them. We shall hold this country and keep it

as a citadel for the British speaking race and as a place where

civilisation will persist." On 10 December HMS Prince of Wales and HMS

Repulse were both sunk by Japanese bombers off the Malayan coast. These

had been the last major battleships standing between Japan and the rest

of Asia, Australia and the Pacific, except for a few survivors of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Curtin cabled Roosevelt and Churchill on December 23: "The fall of

Singapore would mean the isolation of the Philippines, the fall of the

Netherlands East Indies and attempts to smother all other bases. It is

in your power to meet the situation... we would gladly accept United

States commander in Pacific area. Please consider this as a matter of

urgency." Curtin took several crucial decisions. On 26 December, the Melbourne Herald published a New Year's

message from Curtin, who wrote: "We look for a solid and impregnable

barrier of the Democracies against the three Axis powers, and we refuse

to accept the dictum that the Pacific struggle must be treated as a

subordinate segment of the general conflict. By that it is not meant

that any one of the other theatres of war is of less importance than

the Pacific, but that Australia asks for a concerted plan evoking the

greatest strength at the Democracies' disposal, determined upon hurling

Japan back. The Australian Government, therefore regards the Pacific

struggle as primarily one in which the United States and Australia must

have the fullest say in the direction of the Democracies' fighting

plan. Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it clear that

Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional

links or kinship with the United Kingdom. We know the problems that the

United Kingdom faces. We know the dangers of dispersal of strength, but

we know too, that Australia can go and Britain can still hold on. We

are, therefore, determined that Australia shall not go, and we shall

exert all our energies towards the shaping of a plan, with the United

States as its keystone, which will give to our country some confidence

of being able to hold out until the tide of battle swings against the

enemy." This historic speech is one of the most important in

Australia's short history. It marks the turning point in Australia's

relationship with its founding country, the United Kingdom. Many felt

that Prime Minister Curtin was abandoning the ties with Great Britain

without any solid partnership with the United States. This speech also

received criticism at high levels of government in Australia, the UK

and the US; it angered Winston Churchill, and President Roosevelt said it "smacked of panic". The article nevertheless achieved the effect of drawing attention to the possibility that Australia would be invaded by Japan.

Before this speech the Australian response to the war effort was

troubled by attitudes swinging from "she'll be right" to gossip driven

panic. Curtin formed a close working relationship with the Allied Supreme Commander in the South West Pacific Area, General Douglas MacArthur. Curtin realised that Australia would be ignored unless it had a strong

voice in Washington, and he wanted that voice to be MacArthur's. He

gave control of Australian forces to MacArthur, directing Australian

commanders to treat MacArthur's orders as coming from the Australian

government. The Australian government had agreed that the Australian Army's I Corps – centred on the 6th and 7th Infantry Divisions – would be transferred from North Africa to the American - British - Dutch - Australian Command, in the Netherlands East Indies.

Singapore fell on 15 February 1942. It was Australia's worst military

disaster since Gallipolli. The 8th Division was taken into captivity, a

total of about 15,384 men, although Major-General Bennett managed to

escape. In February, following the fall of Singapore and the loss of the 8th Division, Churchill attempted to divert I Corps to reinforce British troops in Burma,

without Australian approval. Curtin insisted that it return to

Australia, although he agreed that the main body of the 6th Division

could garrison Ceylon. The Japanese threat was underlined on 19 February, when Japan bombed Darwin, the first of many air raids on northern Australia. By the end of 1942, the results of the battles of the Coral Sea, Milne Bay and on the Kokoda Track had averted the perceived threat of invasion. Curtin also expanded the terms of the Defence Act, so that conscripted Militia soldiers

could be deployed outside Australia to "such other territories in the

South-west Pacific Area as the Governor General proclaims as being

territories associated with the defence of Australia". This met opposition from most of Curtin's old friends on the left, and from many of his colleagues, led by Arthur Calwell. This was despite Curtin furiously opposing conscription during World War I, and again in 1939 when it was introduced by the Menzies government.

The stress of this bitter battle inside his own party took a great toll

on Curtin's health, never robust even at the best of times. He suffered

all his life from stress related illnesses, and he also smoked heavily.

It became common practice during these years for Curtin and many others

in government to work sixteen hours a day. At the 1943 election,

Curtin led Labor to its greatest election victory, with two-thirds of

seats and a two party preferred vote of 58.2 percent in the House of Representatives. Labor also won the primary vote in all states and thus all 19 seats in the Senate, to hold a total of 22 of 36 seats. Bouyed by the success of the 1943 election,

Curtin tried to centralise power by holding a referendum which would

give the government control of the economy and resources for five

years after the war was won. The 1944 Australian Referendum was held on 19 August 1944. It contained one referendum question. Do

you approve of the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution

entitled 'Constitution Alteration (Post-War Reconstruction and

Democratic Rights) 1944'? Constitution

Alteration (Post-War Reconstruction and Democratic Rights) 1944 was

known as the 14 powers, or 14 points referendum. It sought to give the

government power over a period of five years, to legislate on a wide

variety of matters. The referendum was defeated. In

1944, when he travelled to Washington and London for meetings with

Roosevelt, Churchill and other Allied leaders, he already had heart

disease, and in early 1945 his health deteriorated still more

obviously. On 5 July 1945, at the age of 60, Curtin died, the only

Prime Minister to die at The Lodge. He was the second Australian Prime Minister to die in office within six years. His body was returned to Perth on a RAAF Dakota escorted by a flight of nine fighter aircraft. He was buried at Karrakatta Cemetery in Perth; the service was attended by over 30,000 at the cemetery with many more lining the streets. MacArthur said of Curtin that "the preservation of Australia from invasion will be his immemorial monument". He was briefly succeeded as Prime Minister by Frank Forde, then a week later, after a party ballot, by Ben Chifley. Curtin is credited with leading the Australian Labor Party to

its best federal election success in history, with a record 55.1

percent of the primary half-senate vote, winning all seats, and a two party preferred lower house estimate of 58.2 percent at the 1943 election, winning two-thirds of seats. One

important legacy of Curtin's was the significant expansion of social

services under his leadership. In 1942, uniform taxation was imposed on

the various states, which enabled the Curtin Government to set up a far-reaching, federally administered range of social services. These included a widows’ pension (1942), maternity benefits for Aborigines (1942), funeral benefits (1943),

a wife’s allowance (1943), additional allowances for the children of

pensioners (1943), unemployment, sickness and Special Benefits (1945), and pharmaceutical benefits (1945).

Substantial improvements to pensions were made, with invalidity and

old-age pensions increased, the qualifying period of residence for age

pensions halved, and the means test liberalised.

Other social security benefits were significantly increased, while

child endowment was liberalised, a scheme of vocational training for

invalid pensioners was set up, and pensions extended to cover aborigines. The expansion of social security under John Curtin was of such significance that, as summed up one historian, “Australia

entered World War II with only a fragmentary welfare provision: by the

end of the war it had constructed a ‘welfare state’”. His

early death and the sentiments it aroused have given Curtin a unique

place in Australian political history. Successive Labor leaders, particularly Bob Hawke and Kim Beazley,

have sought to build on the Curtin tradition of "patriotic Laborism".

Even some political conservatives pay at least formal homage to the

Curtin legend. Immediately after his death the parliament agreed to pay

John Curtin's wife Elsie A£1,000 per annum until legislation was

passed and enacted to pay a pension to past Prime Minister or their spouse after their death. Curtin is commemorated by Curtin University of Technology in Perth, John Curtin College of the Arts in Fremantle, the John Curtin School of Medical Research in Canberra, the John

Curtin Prime Ministerial Library and the John Curtin Hotel on Lygon St,

Carlton, Melbourne. On 14 August 2005, the 60th anniversary of V-P Day, a bronze statue of Curtin was unveiled by Premier Geoff Gallop in front of Fremantle Town Hall. Curtin House in Swanston St, Melbourne is named after him. In 1975 he was honoured on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post.