<Back to Index>

- Chemist Irving Langmuir, 1881

- Novelist Pearl Zane Grey, 1872

- 1st Edo Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, 1543

PAGE SPONSOR

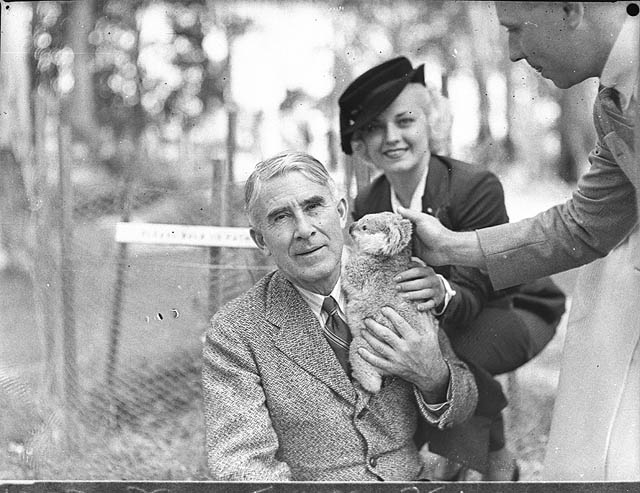

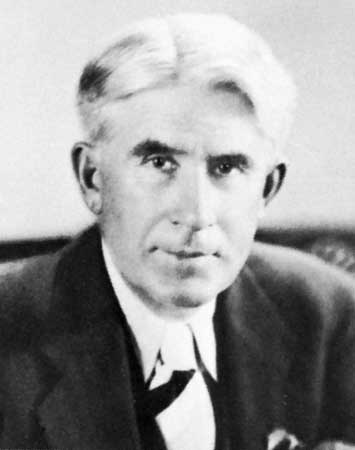

Zane Grey (January 31, 1872 – October 23, 1939) was an American author best known for his popular adventure novels and stories that presented an idealized image of the rugged Old West. As of June 2007, the Internet Movie Database credits Grey with 110 films, one TV episode, and a series, Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theater based loosely on his novels and short stories.

Pearl Zane Gray was born January 31, 1872, in Zanesville, Ohio. He was the fourth of five children born to Lewis M. Gray, a dentist, and his wife, Alice "Allie" Josephine Zane, whose Quaker ancestor Robert Zane came to America in 1673 from England. His family changed the spelling of their last name to Grey after his birth. Later Grey used Zane as his first name. Grey grew up in Zanesville, a city founded by his maternal ancestor Ebenezer Zane, a Revolutionary War patriot, so he felt surrounded by history. Grey developed interests in fishing, baseball, and writing, all which contributed to his writing success. His first three novels memorialized the heroism of his Revolutionary relatives. As a child, Grey frequently engaged in violent brawls. His father punished him with severe beatings. Though irascible and antisocial like his father, Grey was supported by a loving mother and had a father substitute. Muddy Miser was an old man who approved of Grey's love of fishing and writing, and who talked about the advantages of an unconventional life. Despite warnings by Grey’s father to steer clear of Muddy, Grey spent five formative years in the company of the old man.

Grey was an avid reader who stoked his imagination with adventure stories (Robinson Crusoe and Leatherstocking Tales) and dime novels (featuring Buffalo Bill and "Deadwood Dick"). He was enthralled by and crudely copied the great illustrators Howard Pyle and Frederic Remington. He was particularly impressed with Our Western Border, a history of the Ohio frontier which likely inspired his earliest novels. Zane wrote his first story, Jim of the Cave, when he was fifteen. His father tore it to shreds and beat him. Both Grey and his brother Romer were active, athletic boys who were enthusiastic baseball players and fishermen.

A severe financial setback in 1889 caused by a poor investment forced Grey's father, out of embarrassment, to move his family out of Zanesville to start anew in Columbus, Ohio. His father struggled to re-establish his dental practice. Grey helped by making rural house calls and performing basic extractions, which he had learned from his father. He practiced until the state board intervened. Romer helped out by driving a delivery wagon. Grey also worked as a part-time usher in a movie theater and played summer baseball for the Columbus Capitols, with aspirations of becoming a major leaguer. Eventually, Grey was spotted by a baseball scout and received offers to many colleges. Romer also attracted attention and went on to have a pro-baseball career.

Grey chose the University of Pennsylvania on a baseball scholarship, where he studied dentistry and joined Sigma Nu fraternity;

he graduated in 1896. When he arrived at Penn, he had to prove himself

worthy of a scholarship before receiving it. He rose to the occasion by

coming in to pitch against the Riverton club, pitching five scoreless

innings and producing a double in the tenth which contributed to the

win. The Ivy League was

highly competitive and an excellent training ground for future pro

baseball players. Grey was a solid hitter and an excellent pitcher who

relied on a sharply dropping curve ball. When the distance from the

pitcher's mound to the plate was lengthened by ten feet in 1894

(primarily to reduce the dominance of Cy Young’s

pitching), the effectiveness of Grey’s pitching suffered. He was

re-positioned to the outfield. The short, wiry baseball player remained

a campus hero on the strength of his timely hitting. He

was an indifferent scholar, barely achieving a minimum average. Outside

class he spent his time on baseball, pool, and creative writing,

especially poetry. His

shy nature and his teetotaling set him apart and he socialized little.

Grey struggled with the idea of becoming a writer or baseball player

for his career, but unhappily concluded that dentistry was the

practical choice. During a summer break, while playing 'summer nines' in Delphos, Ohio, Grey was charged with, and quietly settled, a paternity suit.

His father paid the $133.40 cost and Grey resumed playing summer

baseball in Delphos. He managed to conceal the episode when he returned

to Penn. Grey went on to play minor league baseball with a team in Newark, New Jersey, and also with the Orange Athletic Club for several years. His brother, Romer Carl "Reddy" Grey (known

as "R.C." to his family) did better and played professionally in the

minor leagues. He played a single major league game in 1903 for the Pittsburgh Pirates. After

graduating, Grey established his practice in New York City under the

name of Dr. Zane Grey in 1896. It was a competitive area but he wanted

to be close to publishers. He began to write in the evening to offset

the tedium of his dental practice. He

struggled financially and emotionally. Grey was a natural writer but

his early efforts were stiff and grammatically weak. Whenever possible,

he played baseball with the Orange Athletic Club in New Jersey, a team

of former collegiate players that was one of the best amateur teams in

the country. Grey often went camping with his brother R.C. in Lackawaxen, Pennsylvania, where they fished in the upper Delaware River.

When canoeing in 1900, Grey met seventeen year old Lina Roth, better

known as "Dolly". They married five years later. Dolly came from a

family of physicians and was studying to be a schoolteacher. They

had a passionate and intense courtship, but quarreled frequently. Grey

suffered bouts of depression, anger, and mood swings, which affected

him most of his life. As he described it, “A hyena lying in ambush —

that

is my black spell! I conquered one mood only to fall prey to the next…

I

wandered about like a lost soul or a man who was conscious of imminent

death." During

his courtship with Dolly, Grey was still in contact with previous

girlfriends and warned her frankly, "But I love to be free. I cannot

change my spots. The ordinary man is satisfied with a moderate income,

a home, wife, children, and all that…. But I am a million miles from

being that kind of man and no amount of trying will ever do any good".

He added, "I shall never lose the spirit of my interest in women." When

they married in 1905, Dolly gave up her teaching career. They moved to

a farmhouse at the convergence of the Delaware and Lackawaxen rivers,

in Lackawaxen, where Grey's mother and sister joined them. (This

historic house is preserved as the Zane Grey Museum.) Grey finally ceased his dental practice to devote full-time to his

nascent literary pursuits. Dolly’s inheritance provided an initial financial cushion. While his wife managed his career and raised their three children, including son Romer Zane Grey,

over the next two decades Grey often spent months away from them. He

fished, wrote and spent time with his many mistresses. While Dolly knew

of his behavior, she seemed to view it as his handicap rather than a

choice. Throughout their life together, he highly valued her management

of his career and their family, and her solid emotional support. In

addition to her considerable editorial skills, she had good business

sense and handled all his contract negotiations with publishers,

agents, and movie studios. All his income was split fifty-fifty with

her; from her "share", she covered all family expenses. Their

considerable correspondence shows evidence of his lasting love for her

despite his indiscretions and personal emotional turmoil. The Greys moved to California in 1918. In 1920 they located in Altadena, California, where Grey bought a prominent mansion on East Mariposa Street, known locally as "Millionaire's Row". Designed by architects Myron Hunt and Elmer Grey (no

relation to the author), the 1907 Mediterranean style house is

acclaimed as the first fireproof home in Altadena, built entirely of

reinforced concrete as

prescribed by the first owner's wife. Grey summed up his feelings for

Altadena with this quote: "In Altadena, I have found those qualities

that make life worth living." (The city uses it in promotions.) It is

in Altadena that he spent time with his beloved mistress Brenda

Montenegro. The two met while hiking Eaton Canyon. Of her he wrote "I

saw her flowing raven mane against the rocks of the canyon. I have seen

the red skin of the Navajo, and the olive of the Spaniards, but

her... her skin looked as if her Creator had in that instant molded her

just for me. I thought it was an apparition. She seemed to be the

embodiment of the West I portray in my books, open and wild." With the help of Dolly’s proofreading and stylistic corrections, Grey gradually improved his style. His first magazine article, A Day on the Delaware, a human interest story about a Grey brothers’ fishing expedition, was published in the May 1902 issue of Recreation magazine. He was elated by selling the article, and he offered reprints to patients in his waiting room. In

writing, Grey found temporary escape from the harshness of his life and

his demons. “Realism is death to me. I cannot stand life as it is.” By this time, he had given up baseball. Grey read Owen Wister’s great Western novel The Virginian. After studying its style and structure in detail, he decided to write a full length story. Grey's first novel, Betty Zane (1903), was a torment to write. When it was rejected by Harper & Brothers, he lapsed into despair. The

novel dramatized the heroism of his ancestor who had saved Fort Henry.

He self-published it, perhaps with funds provided by R.C.'s wealthy

girlfriend Reba Smith or his wife Dolly. From the beginning, vivid description was the strongest aspect of his writing. After attending a lecture in New York in 1907 by Charles Jesse "Buffalo" Jones, western hunter and guide who had co-founded Garden City, Kansas, Grey arranged for a mountain lion hunting trip to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. He

brought along a ‘portable’ camera to document his trips and prove his

adventures. He also began the habit of taking copious notes, not only

of scenery and activities but of dialogue as well. His

first two trips were arduous, but Grey learned much from his rough

compatriot adventurers. He gained the confidence to write convincingly

about the American West, its characters, and its landscape. Treacherous

river crossings, unpredictable beasts, bone chilling cold, searing

heat, parching thirst, bad water, irascible tempers, and heroic

cooperation all became real to him. He wrote, “Surely, of all the gifts

that have come to me from contact with the West, this one of sheer love

of wildness, beauty, color, grandeur, has been the greatest, the most

significant for my work.” Upon returning home in 1909, Grey converted his experiences into a new book, The Last of the Plainsmen, recording the true life adventures of Buffalo Jones. Harper’s editor Ripley Hitchcock rejected

it, the fourth work in a row. He told Grey, “I do not see anything in

this to convince me you can write either narrative or fiction.” Grey

was beside himself and wrote dejectedly, "I don’t know which way to

turn. I cannot decide what to write next. That which I desire to write

does not seem to be what the editors want... I am full of stories and

zeal and fire... yet I am inhibited by doubt, by fear that my feeling

for life is false". The

book was later published by Outing, providing some satisfaction. Grey

next wrote a series of magazine articles and juvenile novels. With the birth of his first child pending, Grey felt a sense of urgency to produce his next novel and his first Western, The Heritage of the Desert.

He completed it in four months in 1910. It quickly became a bestseller.

Grey took his next work to Hitchcock again; this time Harper published

his work, an historical romance in which Mormon characters were of central importance. He continued to write popular novels about Manifest Destiny, the conquest of the Old West, and the behavior of men in elemental conditions. Two years later Grey produced his best known book, Riders of the Purple Sage (1912), his all time best seller, and one of the most successful Western novels of all. Hitchcock

rejected it, but Grey took his manuscript directly to the vice

president of Harper, who accepted it. As Zane Grey had become a

household name, after that, Harper eagerly received all his

manuscripts. Other publishers caught on to the commercial potential of

the Western novel. Max Brand and Ernest Haycox were among the most

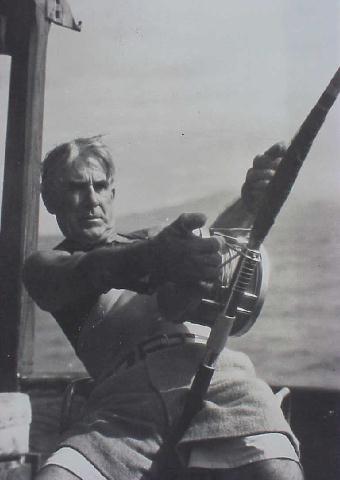

notable of other authors of Westerns. His publishers paired Grey's novels with some of the best illustrators of his time, including N.C. Wyeth, Frank Schoonover, Douglas Duer, Herbert W. Dunton, W.H.D. Koerner, and Charles Russell. Grey

had the time and money to engage in his first and greatest passion —

fishing. From 1918 until 1932 he was a regular contributor to Outdoor Life magazine. He was one of its first celebrity writers. He began to popularize big game fishing. Several times he went deep sea fishing in Florida to relax and to write in solitude. Although

he commented that, “the sea, from which all life springs, has been

equally with the desert my teacher and religion,” Grey was unable to

summon a great sea novel from his imagination. The sea, however, did soothe his moods, reduce his depressions, and gain him the opportunity to harvest deeper thoughts: “The

lure of the sea is some strange magic that makes men love what they

fear. The solitude of the desert is more intimate than that of the sea.

Death on the shifting barren sands seems less insupportable to the

imagination than death out on the boundless ocean, in the awful, windy

emptiness. Man’s bones yearn for dust.” Over

the years, Grey spent part of the year traveling and the rest of the

year using his adventures as the basis for writing stories. Unlike some

writers who could write every day, Grey would have dry spells and then

sudden bursts of energy, where he could wrote as much as 100,000 words

in a month. He encountered fans in most places. He kept a cabin on the Rogue River in Oregon. Other excursions took him to Washington state and Wyoming. He also had a cabin on the Mogollon Rim, in Central Arizona.

He spent a few weeks a year at the cabin from 1923 to 1930. After years

of abandonment of decay, the cabin was restored in 1966 by Bill Goettl, a Phoenix air conditioning magnate, and was opened to the public as a free-of-charge museum. The Dude Fire destroyed the cabin in 1990, and was later rebuilt 25 miles away in the town of Payson. During

the 1930s, Grey continued to write, but the Depression hurt the

publishing industry. His sales fell off. He found it more difficult to

sell serializations. Luckily he had avoided the stock market crash and

continued to secure royalty income. Nearly half of adaptations for film

were made in the 1930s. From

1925 to his death in 1939, Grey traveled more and further from his

family. He became interested in exploring unspoiled lands, particularly

the islands of South Pacific, and New Zealand and Australia. He thought

his beloved Arizona was beginning to be overrun by tourists and speculators. Near the end of his life, Grey looked into the future and wrote: “The

so-called civilization of man and his works shall perish from the

earth, while the shifting sands, the red looming walls, the purple

sage, and the towering monuments, the cast brooding range show no

perceptible change.” The more books Grey sold, the more the established critics, such as Heywood Broun and

Burton Rascoe, would attack him. They claimed his depictions of the

West were too fanciful, too violent, and not faithful to the moral

realities of the frontier. They thought his characters unrealistic and

much larger than life. Broun stated that “the substance of any two Zane

Grey books could be written upon the back of a postage stamp.” T.K. Whipple praised a typical Grey novel as a modern version of the ancient Beowulf saga,

“a battle of passions with one another and with the will, a struggle of

love and hate, or remorse and revenge, of blood, lust, honor,

friendship, anger, grief — all of a grand scale and all incalculable and

mysterious.” But he goes on to criticize Grey’s writing, “His style,

for example, has the stiffness which comes from an imperfect mastery of

the medium. It lacks fluency and facility.” In

truth, as far as veracity was concerned, Grey relied on first hand

experience, careful note taking, and considerable research. Despite

his great popular success and fortune, Grey read the reviews and

sometimes became paralyzed by negative emotions after critical ones. In

1923 a reviewer called Grey’s “moral ideas… decidedly askew”. Grey

reacted with a 20 page treatise “My Answer to the Critics”. He defended

his intentions to produce great literature in the setting of the Old

West. He suggested that critics should ask his readers what they think of his books, and noted actor and fan John Barrymore as an example. Dolly warned him against publishing the treatise, and he retreated from a public confrontation. His novel The Vanishing American (1925), first serialized in The Ladies’ Home Journal in 1922, started a heated debate. People recognized its Navajo hero as patterned after the great athlete Jim Thorpe. Grey portrayed the struggle of the Navajo to

preserve their identity and culture against corrupting influences of

the white government and of missionaries. This viewpoint enraged

religious groups. Grey contended, “I have studied the Navaho Indians

for twelve years. I know their wrongs. The missionaries sent out there

are almost everyone mean, vicious, weak, immoral, useless men.” To

have the book published, Grey agreed to some structural changes. With

this book, Grey completed the most productive period of his writing

career, having laid out most major themes, character types, and

settings. As

with many writers, Grey produced his best work early in his career.

Later he repeated himself. His fans were perfectly happy with the

results, however, and each new book was eagerly anticipated, even after

his death. His Wanderer of the Wasteland is his thinly disguised autobiography. One of his books, “Tales of the Angler’s El Dorado, New Zealand”, helped establish the Bay of Islands in New Zealand as a premier game fishing area. Several of his later writings were based in Australia. Grey

became one of the first millionaire authors. With veracity and

emotional intensity, he connected with his millions of readers

worldwide, during peacetime and war, and inspired many Western writers

who followed him. Zane Grey was a major force in shaping the myths of

the Old West and he helped transition the written Western into other

media. He was the author of over 90 books, some published posthumously

and/or based on serials originally published in magazines. His total book sales exceed 40 million.

He

not only wrote Westerns, but he also authored two hunting books, six

children’s books, two baseball books, and eight fishing books. Many of

them became bestsellers. It is estimated that he wrote over nine

million words in his career. From 1917 – 1926, Grey was in the top ten best seller list nine times, which required sales of over 100,000 copies each time. Even after his death, Harper had a stockpile of manuscripts and continued to publish a new title each year until 1963. During the 1940s and afterwards, paperback sales of Grey’s books exploded. Erle Stanley Gardner, prolific author of mystery novels and the Perry Mason series, said of Grey, he: “had

the knack of tying his characters into the land, and the land into the

story. There were other Western writers who had fast and furious

action, but Zane Grey was the one who could make the action not only

convincing but inevitable, and somehow you got the impression that the

bigness of the country generated a bigness of character.” Grey started his association with Hollywood when William Fox bought the rights to Riders of the Purple Sage for $2,500 in 1916. The ascending arc of Grey’s career matched that of the motion picture industry. It eagerly adapted Western stories to the screen practically from its inception, with Bronco Billy Anderson becoming the first major western star. Legendary director John Ford was then a young stage hand and William S. Hart, who had been a real cowhand, was defining the persona of the film cowboy. The Grey family moved to California to be closer to the film industry and to enable Grey to fish in the Pacific. After his first two books were adapted to the screen, Grey formed his own motion picture company. This allowed him to control production values and faithfulness to his books. After seven films he sold his company to Jesse Lasky, who was a partner of the founder of Paramount Pictures. Paramount made a number of movies based on Grey's writings and hired him as advisor. Many of his films were shot at locations described in his books. Grey

became disenchanted by the commercial exploitation and pirating of his

works. He felt his stories and characters were diluted by being adapted

to film. Nearly fifty of his novels were converted into over one hundred Western movies, the most by any Western author. Shortly after Grey's death, the success of Fritz Lang's Western Union (1941), a film based on one of his books, helped bring about a resurgence in Hollywood westerns. Its costars were Randolph Scott and Robert Young. The period of the 1940s and 1950s included the great works of John Ford, who successfully used the settings of Grey’s novels in Arizona and Utah. The success of Grey's The Lone Star Ranger (a novel later turned into a 1930 film) and King of the Royal Mounted (popular as a series of Big Little Books and comics, later turned into a 1936 film), inspired two radio series by George Trendle (WXYZ, Detroit). Later these were adapted again for television, forming the series The Lone Ranger and Challenge of the Yukon (Sgt. Preston of the Yukon on TV). More of Grey's work was featured in adapted form on the Zane Grey Show, which ran on the Mutual Broadcasting System for five months in the 1940s, and the “Zane Grey Western Theatre”, which had a five-year run of 145 episodes. Many famous actors got their start in films based on Zane Grey books. They included Gary Cooper, Randolph Scott, William Powell, Wallace Beery, Richard Arlen, Buster Crabbe, Shirley Temple, and Fay Wray. Victor Fleming, later director of Gone with the Wind, and Henry Hathaway, who later directed True Grit, both learned their craft on Grey films. Grey's son Loren claims in the introduction to Tales of Tahitian Waters that Zane Grey fished on average 300 days a year through his adult life. Grey and his brother R.C. were frequent visitors to Long Key, Florida, where they helped to establish the Long Key Fishing Club, built by Henry Morrison Flager and was their President from 1917 to 1920. He pioneered the fishing of Boohoo fish (sailfish), and there is a Zane Grey Creek there. Grey

indulged his interest in fishing with visits to Australia and New

Zealand. He first visited New Zealand in 1926 and caught several large fish of great variety, including a mako shark, a ferocious fighter which presented a new challenge. Grey established a base at Otehei Bay Lodge on Urupukapuka Island which

became a magnet for the rich and famous and wrote many articles in

international sporting magazines highlighting the uniqueness of New

Zealand fishing which has produced heavy tackle world records for the

major billfish, striped marlin, black marlin, blue marlin and broadbill. He held numerous world records during this time and invented the teaser, a hookless bait that is still used today to attract fish. Grey fished out of Wedgeport, Nova Scotia, for

many summers and set a world record for the largest blue fin tuna on

August 24, 1924 when he caught one weighing 758 pounds. Grey also

helped establish deep sea sport fishing in New South Wales, Australia, particularly in Bermagui, New South Wales,

which is famous for Marlin fishing. Patron of the Bermagui Sport

Fishing Association for 1936 and 1937, Grey set a number of world

records, and wrote of his experiences in his book "An American Angler

in Australia".

From

1928 on, Grey was a frequent visitor to Tahiti. He fished the

surrounding waters several months at a time and maintained a permanent

fishing camp at Vairao. He claimed that these were the most difficult

waters he had ever fished, but from these waters he also took some of

his most important records, such as the first marlin over 1000 pounds. Grey had built a getaway home in Santa Catalina Island, California,

which now serves as the Zane Grey Pueblo Hotel. Avid fisherman as he

was, he served as president of the Catalina's exclusive fishing club,

the Tuna Club.

Zane Grey died of heart failure on October 23, 1939 at his home in Altadena, California. He was interred at the Union Cemetery in Lackawaxen, Pennsylvania.