<Back to Index>

- Historian Mikhailo Mikhailovich Shcherbatov, 1733

- Sculptor Alexander Calder, 1898

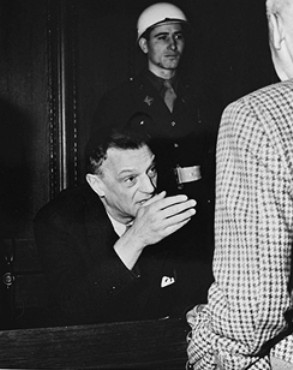

- Federal Chancellor of Austria Arthur Seyss Inquart, 1892

PAGE SPONSOR

Arthur Seyss-Inquart (in German: Seyß-Inquart) (July 22, 1892 – October 16, 1946) was a lawyer and later Nazi official in pre-Anschluss Austria, the Third Reich and for wartime Germany in Poland and the Netherlands. At the Nuremberg Trials, he was found guilty of crimes against humanity and later executed.

Seyss-Inquart was born Arthur Zajtich in 1892 in Stonařov (German: Stannern), Moravia, then part of the Austro - Hungarian Empire, to the ethnic Czech school principal Emil Zajtich and his German speaking wife Auguste Hýrenbach. The family moved to Vienna in 1907 where it changed the Czech Slavic name of "Zajtich" to the invented German "Seyß-Inquart". Seyss-Inquart later went to study law at the University of Vienna. At the beginning of World War I in August 1914 Seyss-Inquart enlisted with the Austrian Army and was given a commission with the Tyrolean Kaiserjäger, subsequently serving in Russia, Romania and also Italy. He was decorated for bravery on a number of occasions and while recovering from wounds in 1917 he completed his final examinations for his degree. Seyss-Inquart had five older siblings: Hedwig (born 1881), Richard (born 3 April 1883, became a Catholic priest, but left the Church and ministry, married in civil ceremony and became Oberregierungsrat and prison superior by 1940 in the Ostmark), Irene (born 1885), Henriette (born 1887) and Robert (born 1891).

In 1911, Seyss-Inquart met Gertrud Maschka. The couple married in 1916 and had three children: Ingeborg Caroline Auguste Seyss-Inquart (born 18 September 1917), Richard Seyss-Inquart (born 22 August 1921) and Dorothea Seyss-Inquart (born 7 May 1928, still alive as of 2008, living in Mattsee, Salzburg.

He went into law after the war and in 1921 set up his own practice. During the early years of the Austrian First Republic, he was close to the Vaterländische Front. A successful lawyer, he was invited to join the cabinet of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss in 1933. Following Dollfuss' murder in 1934, he became a State Councillor from 1937 under Kurt von Schuschnigg. He was not initially a member of the Austrian National Socialist party, although he was sympathetic to many of their views and actions. By 1938, however, Seyss-Inquart knew which way the wind was blowing and became a respectable frontman for the Austrian National Socialists.

In February 1938, Seyss-Inquart was appointed Minister of the Interior by Schuschnigg, after Adolf Hitler had

threatened Schuschnigg with military actions against Austria in the

event of non-compliance. On 11 March 1938, faced with a German invasion aimed at preventing a plebiscite of

independence, Schuschnigg resigned as Austrian Chancellor and

Seyss-Inquart was reluctantly appointed to the position by Austrian

President Wilhelm Miklas. On the next day German troops crossed the border of Austria, at the telegraphed invitation

of Seyss-Inquart, the latter communique having been arranged after the

troops had begun to march, so as to justify the action in the eyes of

the international community. Before his triumphal entry into Vienna,

Hitler had planned to leave Austria as a suppliant state, with an

independent but loyal government. He was carried away, however, by the

wild reception given to the German army by the majority of the Austrian

population, and shortly decreed that Austria would be incorporated into

the Third Reich as the province of Ostmark (Anschluss). Only then, on 13 March 1938, did Seyss-Inquart join the National Socialist party. Seyss-Inquart

drafted the legislative act reducing Austria to a province of Germany

and signed it into law on 13 March. With Hitler's approval he remained

head (Reichsstatthalter) of the newly named Ostmark, with Ernst Kaltenbrunner his chief minister and Josef Burckel as Commissioner for the Reunion of Austria (concerned with the "Jewish Question"). Seyss-Inquart also received an honorary SS rank of Gruppenführer and in May 1939 he was made a Minister without portfolio in Hitler's cabinet. Following the invasion of Poland, Seyss-Inquart became administrative chief for Southern Poland, but did not take up that post before the General Government was created, in which he became a deputy to the Governor General Hans Frank. It is claimed that he was involved in the movement of Polish Jews into ghettos, in the seizure of strategic supplies and in the "extraordinary pacification" of the resistance movement. Following the capitulation of the Low Countries Seyss-Inquart was appointed Reichskommissar for the Occupied Netherlands in

May 1940, charged with directing the civil administration, with

creating close economic collaboration with Germany and with defending the interests of the Reich. He supported the Dutch NSB and allowed them to create a paramilitary Landwacht, which acted as an auxiliary police force. Other political parties were banned in late 1941 and many former government officials were imprisoned at Sint-Michielsgestel.

The administration of the country was largely controlled by

Seyss-Inquart himself. He oversaw the politicization of cultural groups

"right down to the chessplayers' club" through the Nederlandsche Kultuurkamer and set up a number of other politicised associations. He introduced measures to combat resistance and when a widespread strike took place in Amsterdam, Arnhem and Hilversum in May 1943 special summary court martial procedures were brought in and a collective fine of 18 million guilders was

imposed. Up until the liberation Seyss-Inquart condoned the execution

of around 800 people, although some reports put this total at over

1,500, including the execution of people under the so-called "Hostage

Law", the death of political prisoners who were close to being

liberated, the Putten incident, and the reprisal execution of 117 Dutchmen for the attack on SS and Police Leader Hanns Albin Rauter. From July 1944 the majority of Seyss-Inquart's powers were transferred to the military commander in the Netherlands and the Gestapo, though he remained a figure to be reckoned with. There were two small concentration camps in the Netherlands – KZ Herzogenbusch near Vught, Kamp Amersfoort near Amersfoort, and a "Jewish assembly camp" at (camp) Westerbork;

there were a number of other camps variously controlled by the

military, the police, the SS or Seyss-lnquart's administration. These

included a "voluntary labour recruitment" camp at Ommen (Camp Erika).

In total around 530,000 Dutch civilians forcibly worked for the

Germans, of whom 250,000 were sent to factories in Germany. There was

an unsuccessful attempt by Seyss-Inquart to send only workers aged 21

to 23 to Germany, and he refused demands in 1944 for a further 250,000

Dutch workers and in that year sent only 12,000 people. Seyss-Inquart was an unwavering anti-Semite: within a few months of his arrival in the Netherlands,

he took measures to remove Jews from government, the press and leading

positions in industry. Anti-Jewish measures intensified from 1941:

approximately 140,000 Jews were registered, a 'ghetto' was created in Amsterdam and a transit camp was set up at Westerbork. Subsequently, in February 1941, 600 Jews were sent to Buchenwald and Mauthausen concentration camps. Later, the Dutch Jews were sent to Auschwitz. As Allied forces approached in September 1944, the remaining Jews at Westerbork were removed to Theresienstadt. Of 140,000 registered, only 30,000 Dutch Jews survived the war. When Hitler committed suicide in April 1945, Seyss-Inquart declared the setting-up of a new German government under Admiral Karl Dönitz, in which he was to act as the new Foreign Minister, replacing Joachim von Ribbentrop,

who had long since lost Hitler's favour. It was a tribute to the high

regard Hitler felt for his Austrian comrade, at a time when he was

rapidly disowning or being abandoned by so many of the other key

lieutenants of his Third Reich. Unsurprisingly, at such a late stage in

the war, Seyss-Inquart failed to achieve anything in his new office,

and was captured shortly before the end of hostilities. The Dönitz

'government' lasted no more than 20 days. When the Allies advanced into the Netherlands in late 1944, the Nazi regime had attempted to enact a scorched earth policy, and some docks and harbours were destroyed. Seyss-Inquart, however, was in agreement with Armaments Minister Albert Speer over

the futility of such actions, and with the open connivance of many

military commanders, they greatly limited the implementation of the scorched earth orders. At the very end of the so-called "hunger winter", in April 1945, Seyss-Inquart was with difficulty persuaded by the Allies to allow airplanes to drop food for the hungry people of the occupied northwest of the country. Although he knew the war was lost Seyss-Inquart did not want to surrender. This led general Walter Bedell Smith to snap: "Well, in any case, you are going to be shot". "That leaves me cold", Seyss-Inquart replied. To which Bedell Smith then retorted: "It will". He

remained Reichskommissar until 8 May 1945, when, after a meeting with

Karl Dönitz to confirm his blocking of the scorched earth orders,

he was captured aboard a German U-boat by Canadian sailors. At the Nuremberg Trials,

Seyss-Inquart faced charges of conspiracy to commit crimes against

peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes;

and crimes against humanity. During the trial, Gustave Gilbert,

an American Army psychologist, was allowed to examine the Nazi leaders

who were tried at Nuremberg for war crimes. Among other tests, a German

version of the Wechsler - Bellevue IQ test was administered. Arthur Seyss-Inquart scored 141, the second highest among the Nazi leaders tested, behind Hjalmar Schacht. Defended by Gustav Steinbauer, he was nonetheless found guilty of all charges except conspiracy (Controversy remains over the extent of his role as a planner, initiator and wager of wars of aggression.) Upon hearing of his death sentence,

Seyss-Inquart was fatalistic: "Death by hanging... well, in view of the

whole situation, I never expected anything different. It's all right". He

was hanged on 16 October 1946, at the age of 54, together with ten

other Nuremberg defendants. He was the last to mount the scaffold, and

his last words were "I hope that this execution is the last act of the

tragedy of the Second World War and that the lesson taken from this

world war will be that peace and understanding should exist between

peoples. I believe in Germany." Before his execution Seyss-Inquart had returned to Catholicism, received absolution in the sacrament of Confession from prison chaplain Father Bruno Spitzl.