<Back to Index>

- Physicist Wolfgang Gentner, 1906

- Novelist Raymond Thornton Chandler, 1888

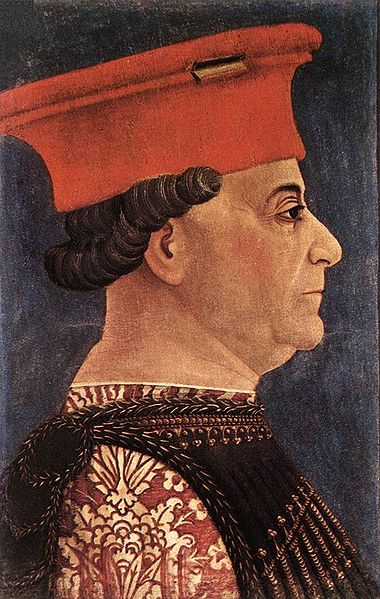

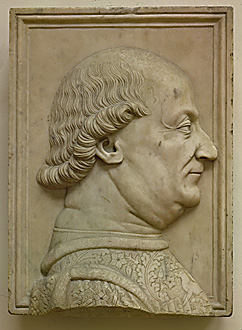

- Duke of Milan Francesco I Sforza, 1401

PAGE SPONSOR

Francesco I Sforza (July 23, 1401 – March 8, 1466) was an Italian condottiero, the founder of the Sforza dynasty in Milan, Italy. He was the brother of Alessandro, with whom he often fought.

Francesco Sforza was born in San Miniato, Tuscany, one of the seven illegitimate sons of the condottiero Muzio Sforza and Lucia da Torsano. He spent his childhood in Tricarico (in the modern Basilicata), the marquisate of which he was granted in 1412 by King Ladislas of Naples. In 1418, he married Polissena Ruffo, a Calabrese noblewoman.

From 1419, he fought alongside his father, soon gaining fame for being able to bend metal bars with his bare hands. He later proved himself to be an expert tactician and very skilled field commander. After the death of his father, he fought initially for the Neapolitan army and then for Pope Martin V and the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti. After some successes, he fell in disgrace and was sent to the castle of Mortara as a prisoner de facto. He regained his status after a successful expedition against Lucca.

In 1431, after a period during which he fought again for the Papal States, he led the Milanese army against Venice; the following year the duke's daughter, Bianca Maria, was betrothed to him. Despite these moves, the wary Filippo Maria never ceased to be distrustful of Sforza. The allegiance of mercenary leaders was dependent, of course, on pay; in 1433 - 1435, Sforza led the Milanese attack on the Papal States, but when he conquered Ancona, in the Marche, he changed sides, obtaining the title of vicar of the city directly from Pope Eugene IV. In 1436 - 39, he served variously both Florence and Venice.

In 1440, his fiefs in the Kingdom of Naples were occupied by King Alfonso I, and, to recover the situation, Sforza reconciled himself with Filippo Visconti. On October 25, 1441, in Cremona, he could finally marry Bianca Maria. The following year, he allied with René of Anjou, pretender to the throne of Naples, and marched against southern Italy. After some initial drawbacks, he defeated the Neapolitan commander Niccolò Piccinino, who had invaded his possessions in Romagna and Marche, through the help of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta (who had married his daughter Polissena) and the Venetians, and could return to Milan.

Sforza later found himself warring against his son Francesco (whom he defeated at the Battle of Montolmo in

1444) and, later, the alliance of Visconti, Eugene IV, and Sigismondo

Malatesta, who had allegedly murdered Polissena. With the help of

Venice, Sforza was again victorious and, in exchange for abandoning the

Venetians, received the title of capitano generale (commander-in-chief) of the Duchy of Milan's armies. After the duke died without a male heir in 1447, fighting broke out to restore the so-called Ambrosian Republic. The name Ambrosian Republic takes its name from St. Ambrose, a popular patron saint of Milan. Sforza received the seigniory of several cities of the duchy, including Pavia and Lodi, and started to carefully plan the conquest of the ephemeral republic, allying with William VIII of Montferrat and

(again) Venice. In 1450, after years of famine, riots raged in the

streets of Milan and the city's senate decided to entrust to him the

dukedom. It was the first time that such a title was handed over by a

lay institution. While the other Italian states gradually recognized

Sforza as the legitimate Duke of Milan, he was never able to obtain

official investiture from the Holy Roman Emperor. That did not come to the Sforza Dukes until 1494, when Emperor

Maximilian formally invested Francesco's son, Lodovico (also known as Ludovico Sforza), as Duke of Milan. Under

his rule (which was moderate and skillful), Sforza modernised the city

and duchy. He created an efficient system of taxation that generated

enormous revenues for the government, his court became a center of Renaissance learning and culture, and the people of Milan grew to love him. In Milan, he founded the Ospedale Maggiore, restored the Palazzo dell' Arengo, and had the Naviglio d' Adda, a channel connecting with the Adda River, built. During Sforza's reign, Florence was under the command of Cosimo de' Medici and the two rulers became close friends. This friendship eventually manifested in first the Peace of Lodi and then the Italian League,

a multi-polar defensive alliance of Italian states that succeeded in

stabilising almost all of Italy for its duration. After the peace,

Sforza renounced part of the conquests in eastern Lombardy obtained by

his condottieri Bartolomeo Colleoni, Ludovico Gonzaga, and Roberto Sanseverino after 1451. As King Alfonso of Naples was among the signatories of the treaty, Sforza also abandoned his long support of the Angevin pretenders to Naples. He also aimed to conquer Genoa, then an Angevin possession; when a revolt broke out there in 1461, he had Spinetta Campofregoso elected as Doge, as his puppet. Sforza occupied Genoa and Savona until 1464. Sforza was the first European ruler to follow a foreign policy based on the concept of the balance of power,

and the first native Italian ruler to conduct extensive diplomacy

outside the peninsula to counter the power of threatening states such

as France. Sforza's policies succeeded in keeping foreign powers from

dominating Italian politics for the rest of the century. Sforza suffered from hydropsy and gout.

In 1462, rumours spread that he was dead and a riot exploded in Milan.

He however survived for four more years, finally dying in March 1466.

He was succeeded as duke by his son, Galeazzo Maria Sforza.

A clay model of the horse for equestrian statue to Francesco I Sforza

was completed by Leonardo Da Vinci in Milan 1492 — but the statue was

never built; it was cast as a equine statue and placed in Milan outside

the racetrack of Ippodromo del Galoppo in 1992. Francesco Sforza is mentioned several times in Niccolò Machiavelli's book The Prince; he is generally praised in that work for his ability to hold his country and as a warning to a prince not to use mercenary troops. He was a moderate patron of the arts. The main humanist of his court was the writer Francesco Filelfo.