<Back to Index>

- Father of Jet Propulsion Frank Whittle, 1907

- Dramatist Ferdinand Jakob Raimann (Raimund), 1790

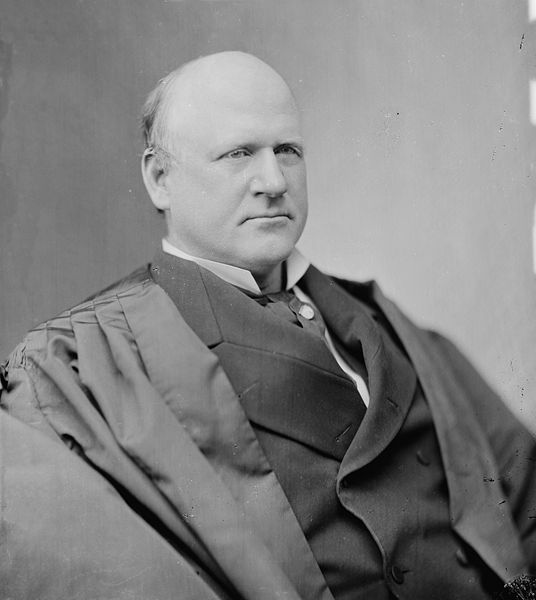

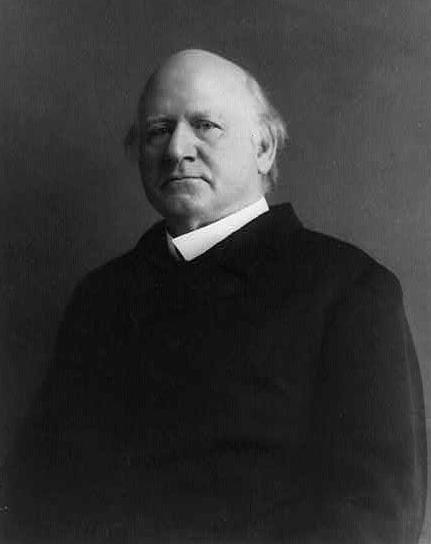

- Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court John Marshall Harlan, 1833

PAGE SPONSOR

John Marshall Harlan (June 1, 1833 – October 14, 1911) was a Kentucky lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court. He is most notable as the lone dissenter in the infamous Civil Rights Cases (1883), and Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which, respectively, struck down as unconstitutional federal anti-discrimination legislation and upheld Southern segregation statutes.

Harlan was born into a prominent Kentucky slaveholding family whose presence in the region dated back to 1779. Harlan's father was James Harlan, a lawyer and politician; his mother, Elizabeth, née Davenport, was the daughter of a pioneer from Virginia. After attending school in Frankfort, Harlan enrolled at Centre College, where he was a member of Beta Theta Pi and graduated with honors. Though his mother wanted Harlan to become a merchant, James insisted that his son follow him into the legal profession, and Harlan joined his father's law practice in 1852. Yet while James Harlan could have trained his son in the office as was the norm in that era, he sent John to attend law school at Transylvania University in 1853, where George Robertson and Thomas Alexander Marshall were among his instructors.

A member of the Whig Party like his father, Harlan got an early start in politics when, in 1851, he was offered the post of adjutant general of the state by the governor at that time, John L. Helm. He served in the post for the next eight years, which gave him a statewide presence and familiarized him with many of Kentucky's leading political figures. With the Whig Party's dissolution in the early 1850s, he shifted his affiliation to the Know Nothings, despite his discomfort with their opposition to Catholicism. Harlan's personal popularity within the state was such that he was able to survive the decline of the Know Nothing movement in the late 1850s, winning election as the county judge for Franklin County, Kentucky, in 1858. The following year, he renounced his allegiance to the Know Nothings and joined the state's Opposition Party, serving as their candidate in an unsuccessful attempt to defeat William E. Simms for the seat in Kentucky's 8th congressional district.

During the 1860 presidential election, Harlan supported the Constitutional Union candidate, John Bell. In the secession crisis that followed Abraham Lincoln's victory, Harlan sought to prevent Kentucky from seceding. When the state legislature voted to create a new militia Harlan organized and led a company of zouaves before recruiting a company that was mustered into the service as the 10th Kentucky Infantry. Harlan served in the Western theater until the death of his father James in February 1863, whereupon Harlan resigned his commission as colonel and returned to Frankfort in order to support his family.

Three weeks after leaving the army, Harlan was nominated by the Union Party as their nominee to become the Attorney General of Kentucky. Campaigning on a platform of vigorous prosecution of the war, he won the election by a considerable margin. As attorney general for the state, Harlan issued legal opinions and advocated for the state in a number of court cases. Party politics, however, occupied much of his time; Harlan campaigned for Democrat George McClellan in the 1864 presidential election and worked as a junior partner to the state Democratic party in the aftermath of the Civil War. After losing a bid for reelection as attorney general, Harlan joined the Republican Party in 1868.

Moving to Louisville, Harlan formed a partnership with John E. Newman, a former circuit court judge and, like Harlan, a Unionist turned Republican. There their firm prospered, and they took in a new partner, Benjamin Bristow, in 1870. In addition to his legal practice, Harlan worked to build up the Republican Party organization in the state, and ran unsuccessfully as the party's nominee for governor of Kentucky in both 1871 and 1875. Despite his defeats, he earned a reputation as a campaign speaker and Republican activist. In the 1876 presidential election, Harlan worked to nominate Bristow as the Republican party's nominee, though when Rutherford B. Hayes emerged as the compromise candidate, Harlan switched his delegation's votes and subsequently campaigned on Hayes's behalf.

Though considered for a number of positions in the new administration, most notably for Attorney General,

initially the only job Harlan was offered was as a member of a

commission sent to Louisiana to resolve disputed statewide elections

there. Justice David Davis, however, had resigned from the Supreme Court in January 1877 after being selected as a United States Senator by the Illinois General Assembly.

Seeking a replacement, Hayes settled on Harlan, and formally submitted

his name to the Senate on October 16. Though Harlan's nomination

prompted some criticism from Republican stalwarts, he was confirmed unanimously on November 29, 1877. Harlan

greatly enjoyed his time as a justice, which would last for the

remainder of his life. From the start he established good relationships

with his fellow justices, and was close friends with a number of them.

Yet money problems continually plagued him, particularly as he began to

put his three sons through college. Debt was a constant concern, and in

the early 1880s he considered resigning from the Court and returning to

private practice. Though he ultimately elected to remain on the Court,

Harlan supplemented his income by teaching constitutional law at the

Columbian Law School, which later became the law school of George Washington University. When Harlan began his service the Supreme Court faced a heavy workload that consisted primarily of diversity and removal cases, with constitutional issues rare. Justices also rode circuit in the various federal judicial circuits; though these usually corresponded to the region from which the justice was appointed, Harlan was assigned the Seventh Circuit due to his junior status. Harlan rode the Seventh Circuit until 1896, when he switched to his home circuit, the Sixth, upon the death of its previous holder, Justice Howell Edmunds Jackson. As

the Court moved away from interpreting the Reconstruction Amendments to

protect Black Americans, Harlan wrote several eloquent dissents in

support of equal rights for Black Americans and racial equality. In the Civil Rights Cases (1883),

the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, holding

that the act exceeded Congressional powers. Harlan alone dissented,

vigorously, charging that the majority had subverted the Reconstruction

Amendments: "The substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the

constitution have been sacrificed by a subtle and ingenious verbal

criticism." Harlan also dissented in Giles v. Harris (1903), a case challenging the use of grandfather clauses to restrict voting rolls and de facto exclude blacks. Harlan did not embrace the idea of full social racial equality. In his Plessy dissent, Harlan wrote that [T]he

white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so

it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in

power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it

remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of

constitutional liberty. Harlan also exhibited antipathy toward other races, such as Chinese. In 1898 Harlan joined Chief Justice Fuller's dissent in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, dissenting

from the Court's holding that persons of Chinese descent born in the

United States were citizens by birth. Fuller and Harlan denounced the

presence within our territory of large numbers of Chinese laborers, of

a distinct race and religion, remaining strangers in the land, residing

apart by themselves, tenaciously adhering to the customs and usage of

their own country, unfamiliar with our institutions and religion, and

apparently incapable of assimilating with our people. Harlan was the first justice to argue that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated the Bill of Rights (making rights guarantees applicable to the individual states), in Hurtado v. California (1884). His argument was later adopted by Hugo Black.

Today, most of the protections of the Bill of Rights and Civil War

amendments incorporated, though not by the theory advanced by Harlan. Harlan was also the most stridently anti-imperialist justice on the Supreme Court, arguing consistently in the Insular Cases that

the Constitution did not permit the demarcation of different rights

between citizens of the states and the residents of newly acquired territories in the Philippines, Hawaii, Guam and Puerto Rico, a view that was consistently in the minority. In Hawaii v. Mankichi (1903)

his opinion stated: "If the principles now announced should become

firmly established, the time may not be far distant when, under the

exactions of trade and commerce, and to gratify an ambition to become

the dominant power in all the earth, the United States will acquire

territories in every direction... whose inhabitants will be regarded as

'subjects' or 'dependent peoples,' to be controlled as Congress may see

fit... which will engraft on our republican institutions a colonial system

entirely foreign to the genius of our Government and abhorrent to the

principles that underlie and pervade our Constitution." Harlan's

partial dissent in the 1911 Standard Oil anti-trust decision (Standard

Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, 221 U.S. 1) penetratingly

addressed issues of statutory construction reaching beyond the Sherman

Anti-Trust Act itself. Harlan dissented in Lochner v. New York,

though he agreed with the majority "that there is a liberty of contract

which cannot be violated even under the sanction of direct legislative

enactment." In 1896, the Supreme Court handed down one of the most infamous decisions in U.S. history, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which established the doctrine of "separate but equal" as it legitimized both Southern and Northern segregation practices. The Court, speaking through Justice Henry B. Brown,

held that separation of the races was not inherently unequal, and any

inferiority felt by blacks at having to use separate facilities was an

illusion: "We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's

argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of

the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If

this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but

solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon

it." (While

the Court held that separate facilities had to be equal, in practice

the facilities designated for blacks were invariably inferior.) Alone

in dissent, and ironic in that his family had owned slaves, Harlan

argued that the Louisiana law at issue, which forced separation of

white and black passengers on railway cars, was a "badge of servitude" that degraded African - Americans, and correctly predicted that the Court's ruling would become as infamous as its ruling in the Dred Scott case. He wrote: If

evils will result from the commingling of the two races upon public

highways established for the benefit of all, they will be infinitely

less than those that will surely come from state legislation regulating

the enjoyment of civil rights upon the basis of race. We boast of the

freedom enjoyed by our people above all other peoples. But it is

difficult to reconcile that boast with a state of the law which,

practically, puts the brand of servitude and degradation upon a large

class of our fellow citizens, our equals before the law. The thin

disguise of 'equal' accommodations for passengers in railroad coaches

will not mislead any one, nor atone for the wrong this day done. In

1856, Harlan married Malvina French Shanklin, the daughter of an

Indiana businessman. Theirs was a happy marriage, which lasted until

Harlan's death. Together they had six children, three sons and three

daughters. Their eldest son, Richard, became a Presbyterian minister

and educator who served as president of Lake Forest College from 1901 until 1906. Their second son, James S. Harlan, practiced in Chicago and served as attorney general of Puerto Rico before being appointed to the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1906 and becoming that body's chairman in 1914. Their youngest son, John Maynard, also practiced in Chicago and served as an alderman before running unsuccessfully for mayor in both 1897 and 1905; John Maynard's son, John Marshall Harlan II, served as a Supreme Court Associate Justice from 1955 until 1971. It is also said that Harlan's attitudes towards civil rights were influenced by the social principles of the Presbyterian Church. During his tenure as a Justice, he taught a Sunday school class at a Presbyterian church in Washington, DC. Harlan died on October 14, 1911, after 33 years with the Supreme Court, the third longest tenure on the court up to that time (and the sixth longest ever). He was buried in Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C. where his body resides along with those of three other justices. There are collections of Harlan's papers at the University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky, and at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.. Both are open for research. Other papers are collected at many other libraries. Named for Justice Harlan, the "Harlan Scholars" of the University of Louisville / Louis D. Brandeis School of Law, is an undergraduate organization for students interested in attending law school. Centre

College, Harlan's alma mater, instituted the John Marshall Harlan

Professorship in Government in 1994 in honor of Harlan's reputation as

one of the Supreme Court's greatest justices. In

2009, with the 200th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's birth coinciding

with the election of the first black American president, Harlan's views

on civil rights - far ahead of his time - were celebrated and

remembered by many.

“ The

white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so

it is in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in

power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time if it

remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of

constitutional liberty. But in view of the constitution, in the eye of

the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class

of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind,

and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of

civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is

the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no

account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as

guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved... ”