<Back to Index>

- Geologist Louis Constant Prévost, 1787

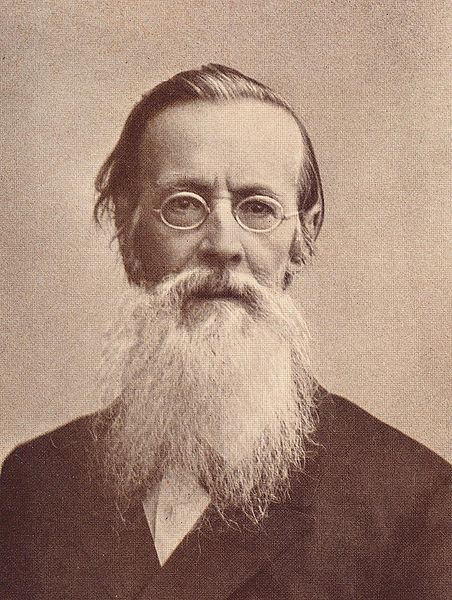

- Poet Apollon Nikolayevich Maykov, 1821

- 1st President of Mali Modibo Keïta, 1915

PAGE SPONSOR

Apollon Nikolayevich Maykov (or Maikov) (Russian: Аполло́н Никола́евич Ма́йков, June 4 [O.S. May 23] 1821, Moscow – March 20 [O.S. March 8] 1897, Saint Petersburg) was a Russian poet.

He was born into the artistic family of Nikolay Apollonovich Maykov, a painter and an academic. In 1834 the family moved to Petersburg. In 1837 - 1841 Maykov studied law at Saint Petersburg University. At first he was attracted to painting, but he soon dedicated his life to poetry. His first publications appeared in 1840 in the Odessa Almanac.

After Nicholas I gave Maykov a stipend for his first book in 1842, he traveled abroad, to Italy, France, Saxony, and Austria. Maykov returned to Petersburg in 1844 and began to work as a librarian's assistant in the Rumyantsev Museum. He frequently met with other famous literati of the day, such as Belinsky, Nekrasov, and Turgenev.

His lyric poetry often showcases images of Russian villages, nature, and Russian history. His love for ancient Greece and Rome, which he studied for much of his life, is also reflected in his works. He spent four years translating the epic The Tale of Igor's Campaign into modern Russian poetry (finished in 1870). He translated the folklore of Belarus, Greece, Serbia, Spain, and other countries, as well as the works of Heine, Adam Mickiewicz, Goethe, etc. Many of Maykov's poems were put to music by N. Rimsky - Korsakov and Tchaikovsky.

D.S. Mirsky called Maykov "the most representative poet of the age," but added:

Máykov was mildly "poetical" and mildly realistic; mildly tendentious, and never emotional. Images are always the principal thing in his poems. Some of them (always subject to the restriction that he had no style and no diction) are happy discoveries, like the short and very well-known poems on spring and rain. But his more realistic poems are spoiled by sentimentality, and his more "poetic" poems hopelessly inadequate — their beauty is mere mid Victorian tinsel. Few of his more ambitious attempts are successful.

He also wrote some prose, which has not gained any significant recognition. After 1880, Maykov wrote almost nothing new, spending his time correcting his prior creations in preparation for the publication of his collected works. In the last years of his life, he was the chairman of the committee for censorship, where he served since 1852.