<Back to Index>

- Chemist Robert Sanderson Mulliken, 1896

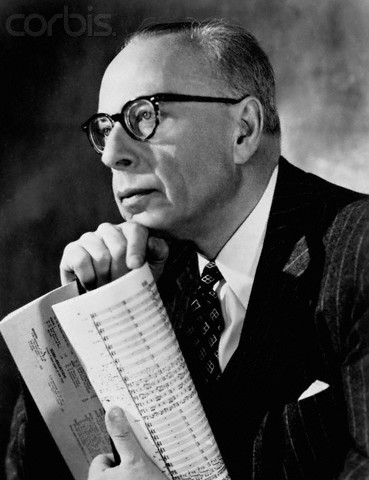

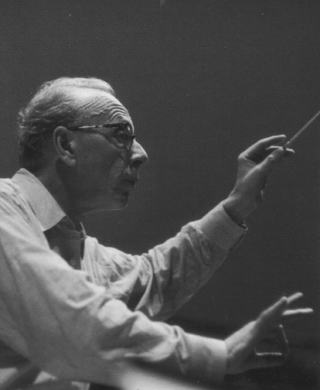

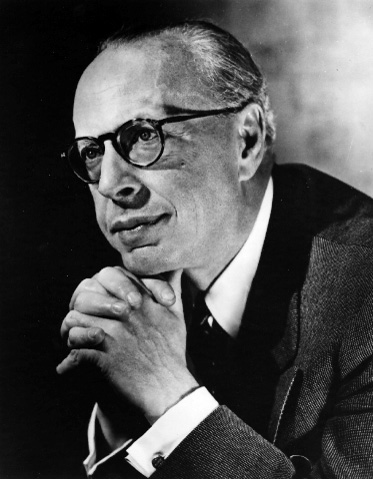

- Conductor György Széll, 1897

- King of Portugal and the Algarves João III, 1502

PAGE SPONSOR

George Szell (June 7, 1897 – July 30, 1970), originally György Széll or Georg Szell, was a Hungarian born American conductor and composer. He is remembered today for his long and successful tenure as music director of the Cleveland Orchestra, and for the recordings of the standard classical repertoire he made in Cleveland and with other orchestras.

Szell

came to Cleveland in 1946 to take over a respected if undersized

orchestra, which was struggling to recover from the disruptions of World War II.

By the time of his death he was credited, to quote the critic Donal

Henahan, with having built it into "what many critics regarded as the

world's keenest symphonic instrument." Through

his recordings, Szell has remained a presence in the classical music

world long after his death, and his name remains synonymous with that

of the Cleveland Orchestra. While on tour with the Orchestra in the

late 1980s, then-Music Director Christoph von Dohnányi remarked, "We give a great concert, and George Szell gets a great review." Szell was born in Budapest but grew up in Vienna. He began his formal music training as a pianist, studying with Richard Robert. One of Robert's other students was Rudolf Serkin; Szell and Serkin became lifelong friends and musical collaborators. In addition to the piano, Szell studied composition with Eusebius Mandyczewski (a personal friend of Brahms), and with Max Reger for

a brief period. Although his work as a composer is virtually unknown

today, when he was fourteen Szell signed a ten year exclusive

publishing contract with Universal Edition in Vienna. In addition to

writing original pieces, he arranged Bedřich Smetana's String Quartet No. 1, From My Life, for orchestra. At age eleven, Szell began touring Europe as a pianist and composer, making his London debut at that age. Newspapers declared him "the next Mozart."

Throughout his teenage years he performed with orchestras in this dual

role, eventually making appearances as composer, pianist and conductor,

as he did with the Berlin Philharmonic at age seventeen. Szell

quickly realized that he was never going to make a career out of being

a composer or pianist, and that he much preferred the artistic control

he could achieve as a conductor. He made an unplanned public conducting

debut when he was seventeen, while vacationing with his family at a

summer resort. The Vienna Symphony's conductor had injured his arm, and

Szell was asked to substitute. Szell quickly turned to conducting

full time. Though he abandoned composing, throughout the rest of his

life he occasionally played the piano with chamber ensembles and as an

accompanist. Despite his rare appearances as a pianist after his teens, he remained in good form. During his Cleveland years he occasionally would demonstrate to guest pianists how he thought they should play a certain passage. In 1915, at the age of 18, Szell won an appointment with Berlin's Royal Court Opera (now known as the Staatsoper). There, he was befriended by its Music Director, Richard Strauss.

Strauss instantly recognized Szell's talent and was particularly

impressed with how well the teenager conducted his own music –- Strauss

once said that he could die a happy man knowing that there was someone

who performed his music so perfectly. In fact, Szell ended up

conducting part of the world premiere recording of Don Juan for Strauss. The composer had arranged for Szell to rehearse the orchestra

for him, but having overslept, showed up an hour late to the recording

session. Since the recording session was already paid for, and only

Szell was there, Szell conducted the first half of the recording (since

no more than four minutes of music could fit onto one side of a 78, the

music was broken up into four sections). Strauss arrived as Szell was

finishing conducting the second part; he exclaimed that what he heard

was so good that it could go out under his own name. Strauss went on to

record the last two parts, leaving the Szell conducted half as part of

the full world premiere recording of Don Juan. Szell

credited Strauss as being a major influence on his conducting style.

Much of his baton technique, the Cleveland Orchestra’s lean,

transparent sound, and Szell's willingness to be an orchestra builder

all came from Strauss. The two remained friends after Szell left the

Royal Court Opera in 1919; even after World War II, when Szell had

settled in the United States, Strauss kept track of how his protégé was doing. In the fifteen years during and after World War I Szell worked with opera houses and orchestras in Europe: in Berlin, Strasbourg — where he succeeded Otto Klemperer at the Municipal Theatre — Prague, Darmstadt, Düsseldorf, and Glasgow, before becoming principal conductor, in 1924, of the Berlin Staatsoper, which had replaced the Royal Opera. In 1930, Szell made his United States debut with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. At this time he was better known as an opera conductor than an orchestral one. At

the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, Szell was returning via the U.S.

from an Australian tour; he ended up settling with his family in New York City. After

spending a year teaching, Szell began to receive frequent guest

conducting invitations. Important among these invitations was a series

of four concerts with Arturo Toscanini’s NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1941. In 1942 he made his Metropolitan Opera debut; he conducted the company regularly for the next four years. In 1943 he made his New York Philharmonic debut. In 1946 he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. In 1946, Szell was asked to become the Music Director of the Cleveland Orchestra. At the time the Cleveland Orchestra was a highly regarded regional American orchestra (the top tier American orchestras were Philadelphia Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic and NBC Symphony Orchestra).

For Szell, working in Cleveland would represent an opportunity to

create his own personal ideal orchestra, one which would combine the

virtuosity of the best American ensembles, with the homogeneity of tone

of the best European orchestras. Szell made it clear to the trustees of

the Orchestra that if they wanted him to be their next conductor, they

would have to agree to give him total artistic control of the

Orchestra; they agreed. He held this post until his death. The

next decade was spent firing musicians, carefully hiring replacements,

increasing the orchestra's roster to over one hundred players, and

relentlessly drilling the orchestra. Szell's rehearsals were legendary

for their intensity. Absolute perfection was demanded from every

player. Musicians would be dismissed on the spot for making too many

mistakes or simply questioning Szell's authority. Although Szell was

not alone in this practice — Toscanini was nothing if not dictatorial —

such firings would not happen today: musicians' unions are much

stronger now than they were then. If Szell heard a player practicing

backstage before a concert and did not like what he heard, he would not

hesitate to berate the musician and give detailed notes on how the

music should be played, despite the concert being minutes away. Szell’s

autocratic style extended to giving suggestions to the Severance Hall janitorial staff on mopping technique and what brand of toilet paper to use in the restrooms. Szell

proudly boasted: "the Cleveland Orchestra gives seven concerts a week

and the public is invited to two." Some critics found the Orchestra to

sound over-rehearsed in concert, lacking spontaneity. Szell conceded

this critique, saying that the orchestra did much of its best work

during rehearsals. But Szell's high standards paid off. According to

music critic Ted Libbey, "Szell's formidable musicianship and paternal

authority commanded equal measures of respect from the Cleveland

players, who under his baton achieved what was probably the highest

executant standard of any orchestra in the world." By

the end of the 1950s it became clear to the world that the Cleveland

Orchestra, noted for its flawless precision and chamber like sound, had

taken its place alongside the greatest orchestras in America and

Europe. In addition to taking the Orchestra on annual tours to Carnegie Hall and the East Coast, Szell led the orchestra on its first international tours to Europe, the Soviet Union, Australia, and Japan. Szell's manner in rehearsal was that of an autocratic taskmaster. He meticulously prepared for rehearsals and could play the entire score on the piano from memory. Preoccupied with phrasing, transparency, balance and architecture, Szell also insisted upon hitherto unheard of rhythmic discipline from his players. The result was often a level of precision and ensemble playing normally found only in the best string quartets. For all Szell's absolutist methods, many of the orchestra's players were proud of the musical integrity to which he aspired. Video

footage also shows that Szell took care to explain what he wanted and

why, expressed delight when the orchestra produced what he was aiming

for, and avoided over-rehearsing parts that were in good shape. His left hand, which he used to shape each sound, was often called the most graceful in music. As a result of Szell's exactitude and very thorough rehearsals, some musicians and critics have

criticized Szell's music making as lacking emotion. In response to such

criticism, Szell expressed this credo: "The borderline is very thin

between clarity and coolness, self-discipline and severity. There exist

different nuances of warmth — from the chaste warmth of Mozart to the

sensuous warmth of Tchaikovsky, from the noble passion of Fidelio to the lascivious passion of Salome. I cannot pour chocolate sauce over asparagus." He further stated: "It is perfectly legitimate to prefer the hectic, the

arhythmic, the untidy. But to my mind, great artistry is not

disorderliness." He

has been described as a "literalist", playing only what is in the

score. However, Szell was quite prepared to play music in

unconventional ways if he thought the music needed these; and, like

most other conductors before and since, he made many small

modifications to orchestrations and even notes in the works of

Beethoven, Schubert and others. His recordings of the four Schumann symphonies contain alterations to the composer's orchestration.

Szell

primarily conducted works from the core Austro - German classical and

romantic repertoire, from Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, through

Mendelssohn, Schumann and Brahms, and on to Bruckner, Mahler and

Strauss. He said once that as he got older he consciously narrowed his

repertoire, feeling it was "actually my task to do those works which I

thought I'm best qualified to do, and for which a certain tradition is

disappearing with the disappearance of the great conductors who were my

contemporaries and my idols and my unpaid teachers." He

did however program contemporary music; he gave numerous world

premieres in Cleveland, and he was particularly associated with such

composers as Dutilleux, Walton, Prokofiev, Hindemith and Bartók. Szell also helped initiate the Cleveland Orchestra's long association with composer conductor and avant-garde icon Pierre Boulez. At the same time, Szell championed the music of Haydn and Mozart in a period when those composers were little represented in concert programs.

After World War II Szell became closely associated with the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam, where he was a frequent guest conductor and made a number of recordings. He also regularly appeared with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic, and at the Salzburg Festival. From 1942 to 1955, he was an annual guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic and served as Musical Advisor and senior guest conductor of that orchestra in the last year of his life.

Szell

married twice. The first, in 1920 to Olga Band, ended in divorce in

1926. His second marriage, in 1938 to Helene Schultz Teltsch,

originally from Prague, was much happier, and lasted until his death. When

not making music, he was a gourmet cook and an automobile enthusiast.

He regularly refused the services of the orchestra's chauffeur and

drove his own Cadillac to rehearsal until almost the end of his life. He died in Cleveland, Ohio in 1970.

Most of Szell's recordings were made with the Cleveland Orchestra for Epic/Columbia Masterworks/CBS Masterworks (now Sony Classical). He also made recordings with the New York Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. Few of his mono recordings have been reissued. Many live stereo

recordings of repertoire Szell never conducted in the studio exist,

both with the Cleveland Orchestra and other orchestras.