<Back to Index>

- Psychiatrist Aloysius "Alois" Alzheimer, 1864

- Photographer Margaret Bourke White, 1904

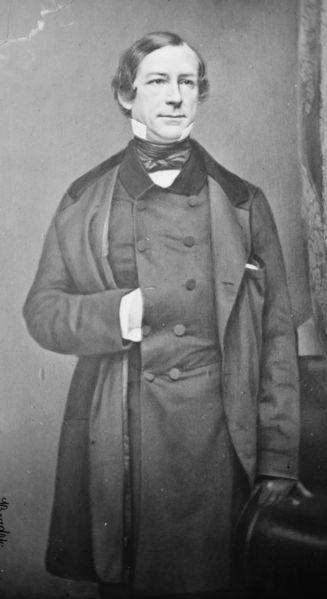

- Mayor of New York City Fernando Wood, 1812

PAGE SPONSOR

Fernando Wood (June 14, 1812 - February 14, 1881) was an American politician of the Democratic Party who is known for being one of the most colorful mayors in the history of New York City; he also served as a United States Representative (1841 – 1843, 1863 – 1865, and 1867 – 1881) and as Chairman of the Committee on Ways and Means in both the 45th and 46th Congress (1877 – 1881).

A successful shipping merchant who became Grand Sachem of the political machine known as Tammany Hall, Wood first served in Congress in 1841. In 1854 he was elected Mayor of New York City. Reelected in 1860 after an electoral loss in 1857 by a narrow majority of 3,000 votes, Wood evinced support for the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War, suggesting to the New York City Council that New York City secede from the Union and declare itself a free city in order to continue its profitable cotton trade with the Confederacy. Wood's Democratic machine was concerned to maintain the revenues (which depended on Southern cotton) that maintained the patronage. Following his service as mayor, Wood returned to the United States Congress.

Wood was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His Spanish sounding forename was chosen by his mother, who found it in an English gothic novel written by George Walker, The Three Spaniards (London,

1800). He moved to New York, where he became a successful shipping

merchant. He was chairman of the chief young men's political

organization in 1839 and was a member of the Tammany Society,

which he used as a vehicle for his political rise. As a member of the

Democratic party, he was elected to Congress in 1841 and served until

1843. In late 1854 Wood was elected Mayor of New York City. The state legislature created the New York Municipal Police in 1845, and Wood continued the efforts of his predecessor Mayor Jacob A. Westervelt to

fight the massive corruption of the force, during his first term as

Mayor (1855 – 1857). He was defeated for re-election in 1858 by a narrow

majority of 3,000 votes, even though the New York gang the Dead Rabbits combed the city's cemeteries for names to add to the voter rolls. In the 1856 - 57 session, Republicans in control of the New York State Legislature at Albany shortened Wood's second term of office from two years to one, and created a Metropolitan Police Force, with Frederick Talmadge as

superintendent, to replace Wood's corrupt Municipal Police. Talmadge

demanded that Wood disband the Municipal Police, but Wood refused, even

in the face of a May 1857 decision by the Supreme Court. Superintendent George W. Matsell, 15 captains and 800 patrolmen of the Municipal Police backed Mayor Wood. Captain

George W. Walling pledged his loyalty to the new Metropolitan Police

and was ordered to arrest Mayor Wood. Wood refused to submit and when

Captain Walling attempted force, New York City Hall was

occupied by 300 Municipal policemen, who promptly tossed Captain

Walling into the street. Fifty Metropolitans in frock coats and plug

hats then marched on City Hall with night sticks in hand. The

Municipals swarmed out and routed the Metropolitans. Fifty-two

policemen were injured in the police riot. The Metropolitan Police Board called out the National Guard, and the Seventh Regiment surrounded

City Hall. A platoon of infantry with fixed bayonets marched into City

Hall and surrounded Mayor Wood who then submitted to arrest. Mayor Wood

was charged with inciting to riot, released on nominal bail and

returned to his office. The

feud continued on through the summer of 1857, with constant

confrontations between the rival police forces. When a Municipal

arrested a criminal, a Metropolitan would come along and release him.

At the police station, an arresting officer would find an alderman and

a magistrate from the opposing side waiting. A hearing would be held on

the spot and the prisoner released on his own recognizance. The

gangs of New York had a field day. Pedestrians were mugged in broad

daylight on Broadway while rival policemen clubbed each other to

determine who had the right to interfere. Soon the gangs were looting

and plundering without interference, but turned on one another in turf

wars, which culminated in the Fourth of July gang battle. The Dead

Rabbits and several other Five Points gangs marched into the Bowery to

do battle with the Bowery Boys and to loot stores. They attacked a

Bowery Boys headquarters with pistols, knives, clubs, iron bars and

huge paving blocks, routing the defenders. The Bowery Boys and their

allies the Atlantic Guards poured into Bayard Street to engage in the

most desperate and largest free-for-all in the city's history. The

Metropolitans attempted to stop the fighting but were severely beaten

and retreated. The Municipals said the battle looked like a

Metropolitan problem and was none of their business. Fernando

Wood served a second mayoral term in 1860 - 1862. Wood was one of many

New York Democrats sympathetic to the Confederacy, called 'Copperheads'

by the staunch Unionists. During his second mayoral term in January

1861, Wood suggested to the City Council that New York secede and

declare itself a free city, to continue its profitable cotton trade

with the Confederacy. Wood's Democratic machine was concerned to

maintain the revenues (which depended on Southern cotton) that

maintained the patronage. (Wood's suggestion was greeted with derision

by the Common Council. Tammany Hall was highly factionalized until

after the Civil War. Wood headed his own organization named Mozart

Hall, not Tammy Hall. New York City commercial interests wanted to

retain their relations with the South, but within the framework of the

Constitution.) Wood's brother Benjamin Wood purchased the New York Daily News in 1860, supporting Stephen A. Douglas, and was elected to Congress, where he made a name as an opponent of pursuing the American Civil War. Subsequent

to serving his second mayoral term, Wood served again in the House of

Representatives from 1863 to 1865, then again from 1867 until his death

in Hot Springs, Arkansas. On

January 15, 1868, Wood was censured for the use of unparliamentary

language. During debate on the floor the House of Representatives, Wood

called a piece of legislation "A monstrosity, a measure the most

infamous of the many infamous acts of this infamous Congress." An

uproar immediately followed this utterance, and Wood was not permitted

to continue. This was followed by a motion by Henry L. Dawes to censure Wood, which passed by a vote of 114-39. Notwithstanding his censure, Wood still managed to defeat Dr. Francis Thomas, the Republican candidate, by a narrow margin in the election of that year. Wood served as Chairman for the Committee on Ways and Means in both the 45th and 46th Congress (1877 – 1881).