<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Jules Antoine Lissajous, 1822

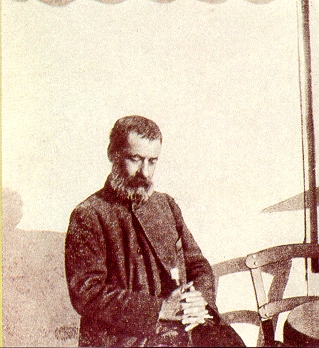

- Writer Alexandros Papadiamantis, 1851

- Italian Revolutionary Francesco Bentivegna, 1820

PAGE SPONSOR

Alexandros Papadiamantis (Greek: Ἀλέξανδρος Παπαδιαμάντης) (March 4, 1851 - 3 January 1911) was a famous and influential Greek writer of the 19th century.

Papadiamantis was born on the island of Skiathos, in the western part of the Aegean Sea. The island would figure prominently in his work. His father was a priest. He moved to Athens as a young man to complete his high school studies, and enrolled in the philosophy faculty of Athens University, but never completed his studies. He returned to his native island in later life, and died there. He supported himself (very meagerly) by writing throughout his adult life, anything from journalism and short stories to several serialized novels. He never married, and was known as a recluse: he was referred to as "kosmokalogeros" (worldly monk). He died of pneumonia.

Papadiamantis' longest works were the serialized novels "The Gypsy Girl," "The Emigrant," and "Merchants of Nations." These were adventures set around the Mediterranean, with rich plots involving captivity, war, pirates, the plague, etc. However, the author is best remembered for his scores of short stories. Written in his own version of the then official language of Greece, "katharevousa" (a "purist" written language heavily influenced by ancient Greek), Papadiamantis' stories are little gems. They provide lucid and lyrical portraits of country life in Skiathos, or urban life in the poorer neighborhoods of Athens, with frequent flashes of deep psychological insight. The nostalgia for a lost island childhood is palpable in most of them; the stories with an urban setting often deal with alienation. Characters are sketched with a deft hand, and they speak in the authentic "demotic" spoken language of the people; island characters lapse into dialect. Papadiamantis' deep Christian faith, complete with the mystical feeling associated with Byzantine liturgy, suffuses many stories. Most of his work is tinged with melancholy, and resonates with empathy with people's suffering, regardless of whether they are saints or sinners, innocent or conflicted. His only saint, in fact, is a poor shepherd who, having warned the islanders, is slaughtered by Saracen pirates after he refuses to abandon his flock for the safety of the fortified town. This particular story, "The Poor Saint," is the closest he comes to a truly religious theme.

An example of Papadiamantis' deep and even-handed feeling for humanity is his acknowledged masterpiece, the novella "The Murderess." It is the story of a Skiathos country midwife, who pities families with many daughters: given their low socioeconomic status, girls can only marry if they provide a dowry, and are therefore a burden to poor families. The midwife crosses the line from pity to what she believes is useful and appropriate action, the "mercy killing" of female newborn babies. When she is discovered she is confronted with a stark fact: her assumption that she was helping was monstrously wrong, and she has betrayed her calling of bringing life, not death, into the world. Pursued, she drowns in the sea while trying to escape. The character of the murderess is depicted with deep empathy and without condemnation. Decades after it was written, it was made into a film by Kostas Ferris.