<Back to Index>

- Astronomer David Fabricius, 1564

- Painter Thomas William Roberts, 1856

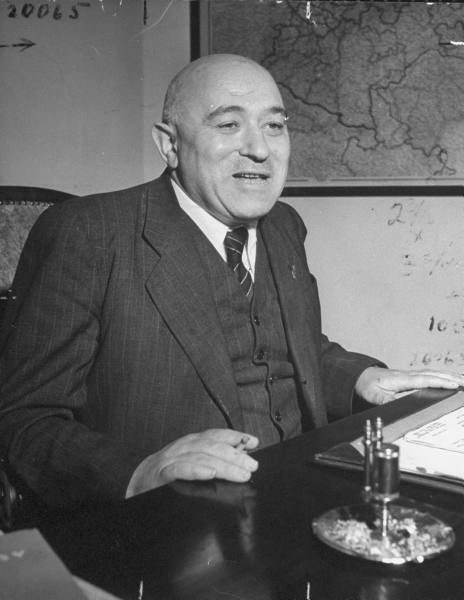

- General Secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party Mátyás Rákosi, 1892

PAGE SPONSOR

Mátyás Rákosi (March 9, 1892 – February 5, 1971) was a Hungarian communist politician. He was born as Mátyás Rosenfeld, in present day Serbia. He was the ruler de facto of the communist Hungary between 1945 and 1956 — first in his capacity as General Secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party (1945 – 1948) and later as General Secretary of the Hungarian Working People's Party (1948 – 1956). His rule was characterised as a Stalinist type dictatorship.

Rákosi was born in Ada, a village in Bács County in what was then the Austro - Hungarian Empire (now in Vojvodina, Serbia). Born into a Jewish family, the fourth son of a grocer (his mother would give birth to seven more children) he later repudiated religion and totally repudiated Judaism, consistent with Communist doctrine, which was atheistic.

He served in the Austro - Hungarian Army during the First World War and was captured on the Eastern Front. After returning to Hungary, he participated in the communist government of Béla Kun; after its fall he fled, eventually to the Soviet Union. After returning to Hungary in

1924 he was imprisoned, and was released to the Soviet Union in 1940,

in exchange for the Hungarian revolutionary banners captured by the

Russian troops at Világos in 1849. In the Soviet Union, he became leader of the Comintern. He returned to Debrecen, Hungary, on January 30, 1945, sent by Soviet leadership, to organize the Communist Party. When the communist government was installed in Hungary, Rákosi was appointed General Secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party (MKP). He was a member of the High National Council from September 27 to December 7, 1945. Rákosi was acting Prime Minister from February 1 to February 4, 1946 and on May 31, 1947. In 1948, the Communists forced the Social Democrats to merge with them to form the Hungarian Working People's Party (MDP).

A year later, elections were held with a single list of candidates;

although non-Communists nominally still figured, they were actually fellow travelers. This marked the onset of undisguised Communist rule in Hungary. Rákosi described himself as "Stalin's best Hungarian disciple" and "Stalin's best pupil." He also invented the term "salami tactics",

which related to his method of eliminating the non-Communist

opposition. By portraying his rivals as either fascists or fascist

sympathizers, he was able to get the non-Communist parties to push out

their more courageous members, leaving only those willing to do the

Communists' bidding. He later said that he destroyed the non-Communist

forces in the country by "cutting them off like slices of salami." At

the height of his rule, he developed a strong cult of personality around himself. Under

Rákosi, an imitator of Stalinist political and economic

programs, and dubbed the “bald murderer,” Hungary experienced one of

the harshest dictatorships in Europe. Approximately 350,000 officials

and intellectuals were purged from 1948 to 1956. Rákosi imposed totalitarian rule on Hungary — arresting, jailing and killing

both real and imagined foes in various waves of Stalin inspired political purges – as the country went into decline. In August 1952 he also became Chairman of the Council of Ministers, but on June 13, 1953, to appease the Soviet Politburo, he was forced to give up the office to Imre Nagy,

yet retained the office of General Secretary. Rákosi led the

attacks on Nagy. On 9 March 1955, the Central Committee of the Hungarian Working People's Party condemned

Nagy for "rightist deviation". Hungarian newspapers joined the attacks

and Nagy was accused of being responsible for the country's economic

problems and on 18 April he was dismissed from his post by a unanimous

vote of the National Assembly. Although Rákosi did not resume

the premiership, he quickly put the country back on its previous course. The

postwar Hungarian economy suffered from multiple challenges. The most

important was the destruction of assets in the war (40% of national

wealth, including all bridges, railways, raw materials, machinery, etc.) Hungary agreed to pay war reparations approximating US$ 300 million, to the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, and to support Soviet garrisons. The Hungarian National Bank in

1946 estimated the cost of reparations as "between 19 and 22 per cent

of the annual national income." In spite of this, after the highest

historical rate of inflation in world history, the new, stable currency

was successfully launched in August 1946 on the basis of the plans of

the

Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party. While consumer goods

production was still low, industrial production exceeded the level of

1938 by 40% in 1949 and tripled by 1953. However,

the backwardness of light industries resulted in frequent shortages,

especially in the provinces, leading to discontent. In addition, the

huge investments in military sectors after the outbreak of the Korean War further

reduced the supply of consumer goods. Because of the shortages, forced

savings (state bond sales to the population) and below inflation wage

increases were introduced. In

spite of the significant and historic achievements in the

industrialisation of the country, because of the discontent and

economic imbalances corrective, though ad-hoc, measures were introduced

1953 that favoured light industries and agriculture. Rákosi was then removed as General Secretary of the Party under pressure from the Soviet Politburo in June 1956 (shortly after Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech), and was replaced by Ernő Gerő.

To remove him from the Hungarian political scene, the Soviet Politburo

forced Rákosi to move to the Soviet Union in 1956, with the

official story being that he was "seeking medical attention." He spent

the rest of his life in the Kirgiz Soviet Socialist Republic.

Shortly before his death, in 1970, Rákosi was finally granted

permission to return to Hungary if he promised not to engage in any

political activities. He refused the deal, and remained in the USSR

where he died in Gorky in 1971. After his death, his ashes were secretly returned to Hungary for burial in the Farkasrét Cemetery in Budapest.