<Back to Index>

- Botanist and Zoologist Georg Wilhelm Steller, 1709

- Librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte, 1749

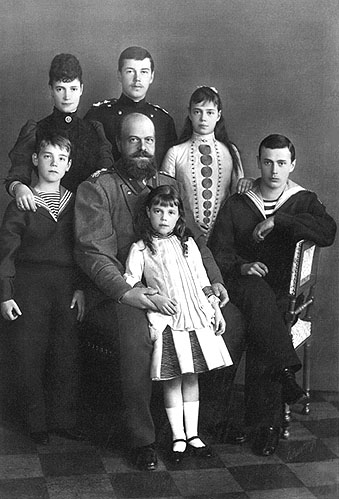

- Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias Alexander III Alexandrovich, 1845

PAGE SPONSOR

Alexander III Alexandrovich (10 March [O.S. 26 February] 1845 – 1 November [O.S. 20 October] 1894) (Russian: Александр III Александрович) reigned as Emperor of Russia from 13 March 1881 until his death in 1894. Unlike his assassinated father, liberal leaning Alexander II, Alexander III is considered by historians to have been a repressive and reactionary tsar.

Alexander III was born in Saint Petersburg, the second son of Czar Alexander II by his wife Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine. In disposition, he bore little resemblance to his soft hearted, liberal father, and still less to his refined, philosophic, sentimental, chivalrous, yet cunning grand uncle Alexander I, who coveted the title of "the first gentleman of Europe". Although an enthusiastic amateur musician and patron of the ballet, he was seen as lacking refinement and elegance. Indeed, he rather relished the idea of being of the same rough texture as the great majority of his subjects. His straightforward, abrupt manner savoured sometimes of gruffness, while his direct, unadorned method of expressing himself harmonized well with his rough hewn, immobile features and somewhat sluggish movements. His education was not such as to soften these peculiarities. He was also noted for his immense physical strength, though the large boil on the left side of his nose caused him to be severely mocked by his contemporaries, hence why he always sat for photographs and portraits with the right side of his face most prominent. Perhaps an account from the memoirs of the artist Alexander Benois best describes an impression of Alexander III:

After a performance of the ballet 'Tsar Kandavl' at the Mariinsky Theatre, I first caught sight of the Emperor. I was struck by the size of the man, and although cumbersome and heavy, he was still a mighty figure. There was indeed something of the muzhik [Russian peasant] about him. The look of his bright eyes made quite an impression on me. As he passed where I was standing, he raised his head for a second, and to this day I can remember what I felt as our eyes met. It was a look as cold as steel, in which there was something threatening, even frightening, and it struck me like a blow. The Tsar's gaze! The look of a man who stood above all others, but who carried a monstrous burden and who every minute had to fear for his life and the lives of those closest to him. In later years I came into contact with the Emperor on several occasions, and I felt not the slightest bit timid. In more ordinary cases Tsar Alexander III could be at once kind, simple, and even almost... homely.

Though

he was destined to be one of the great counter reforming Tsars, during

the first twenty years of his life, Alexander had little prospect of

succeeding to the throne, because he had an elder brother, Nicholas, who seemed of robust constitution. Even

when this elder brother first showed symptoms of delicate health, the

notion that he might die young was never seriously taken; Nicholas was

betrothed to the Princess Dagmar of Denmark. Under

these circumstances, the greatest solicitude was devoted to the

education of Nicholas as Tsarevich, whereas Alexander received only the

perfunctory and inadequate training of an ordinary Grand Duke of that

period, which did not go much beyond secondary instruction, with

practical acquaintance in French, English and German, and a certain amount of military drill. Alexander became heir apparent with

the sudden death of his elder brother in 1865. It was then that he

began to study the principles of law and administration under Konstantin Pobedonostsev, then a professor of civil law at Moscow State University and later (from 1880) chief procurator of the Holy Synod. Pobedonostsev

awakened in his pupil very little love of abstract studies or prolonged

intellectual exertion, but he did influence the character of

Alexander's reign by instilling into the young man's mind the belief

that zeal for Russian Orthodox thought was an essential factor of Russian patriotism and that this was to be specially cultivated by every right-minded Tsar.

On

his deathbed, Alexander's elder brother Nicholas is said to have

expressed the wish that his affianced bride, Princess Dagmar of

Denmark, should marry his successor. This wish was swiftly realized, when on 9 November [O.S. 28 October] 1866 in the Imperial Chapel of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Alexander wed the Princess of Denmark. The

union proved a most happy one and remained unclouded to the end. Unlike

that of his parents, there was no adultery in the marriage. During

those years when he was heir-apparent — 1865 to 1881 — Alexander did not

play a prominent part in public affairs, but he allowed it to become

known that he had certain ideas of his own which did not coincide with

the principles of the existing government.

Alexander

deprecated what he considered undue foreign influence in general, and

German influence in particular, so the adoption of genuine national

principles was off in all spheres of official activity, with a view to

realizing his ideal of a homogeneous Russia — homogeneous in language,

administration and religion. With such ideas and aspirations he could

hardly remain permanently in cordial agreement with his father, who,

though a good patriot according to his lights, had strong German

sympathies, often used the German language in his private relations,

occasionally ridiculed the exaggerations and eccentricities of the Slavophiles and based his foreign policy on the Prussian alliance. The antagonism first appeared publicly during the Franco - Prussian War, when the Tsar supported the cabinet of Berlin and

the Tsarevich did not conceal his sympathies for the French. It

reappeared in an intermittent fashion during the years 1875 – 1879, when the Eastern question produced

so much excitement in all ranks of Russian Society. At first the

Tsarevich was more Slavophile than the government, but his phlegmatic nature

preserved him from many of the exaggerations indulged in by others, and

any of the prevalent popular illusions he may have imbibed were soon

dispelled by personal observation in Bulgaria, where he commanded the left wing of the invading army. Never

consulted on political questions, he confined himself to his military

duties and fulfilled them in a conscientious and unobtrusive manner.

After many mistakes and disappointments, the army reached Constantinople and the Treaty of San Stefano was signed, but much that had been obtained by that important document had to be sacrificed at the Congress of Berlin. Bismarck failed to do what was confidently expected of him by the Russian Tsar.

In return for the Russian support, which had enabled him to create the German Empire, it

was thought that he would help Russia to solve the Eastern question in

accordance with her own interests, but to the surprise and indignation

of the cabinet of Saint Petersburg he confined himself to acting the

part of "honest broker" at the Congress, and shortly afterwards he

ostentatiously contracted an alliance with Austria for the express purpose of counteracting Russian designs in Eastern Europe.

The Tsarevich could point to these results as confirming the views he

had expressed during the Franco - Prussian War, and he drew from them the

practical conclusion that for Russia the best thing to do was to

recover as quickly as possible from her temporary exhaustion and to

prepare for future contingencies by a radical scheme of military and

naval reorganization. In accordance with this conviction, he suggested

that certain reforms should be introduced.

Alexander III engaged in antisemitic policies such as tightening restrictions on where Jews could live in the Pale of Settlement and restricting the occupations that Jews could attain. The pogroms of 1881 occurred at the beginning of Alexander III's reign. Antisemitic policies under both Alexander III and his successor, Nicholas II, encouraged the Jewish emigration to the United States from 1880 on. The administration of Alexander III enacted the May Laws in 1882 that imposed harsh conditions on the Jews as a people for the alleged role of some Jews in the assassination of Alexander II. During

the campaign in Bulgaria he had found by painful experience that grave

disorders and gross corruption existed in the military administration,

and after his return to Saint Petersburg he had discovered that similar

abuses existed in the naval department. For these abuses, several

high-placed personages — among others two of the grand-dukes — were

believed to be responsible, and he called his father's attention to the

subject. His representations were not favourably received. Alexander II

had lost much of the reforming zeal that distinguished the first decade

of his reign, and had no longer the energy required to undertake the

task suggested to him. The consequence was that the relations between

father and son became more strained. The latter must have felt that

there would be no important reforms until he himself succeeded to the

direction of affairs. That change was much nearer at hand than was

commonly supposed. On 13 March 1881 Alexander II was assassinated by a

band of Nihilists, Narodnaya Volya (People's Will), and the autocratic power passed to the hands of his son. In

the last years of his reign, Alexander II had been very concerned by

the spread of Nihilist doctrines and the increasing number of anarchist

conspiracies, and for some time he had hesitated between strengthening

the hand of the executive and making concessions to the widespread

political aspirations of the educated classes. Finally he decided in

favour of the latter course, and on the very day of his death he signed

an ukaz creating a number of consultative commissions that might easily

have been transformed into an assembly of notables. Following the advice of his political mentor Konstantin Pobedonostsev,

Alexander III determined to adopt the opposite policy. He at once

canceled the ukaz before it was published, and in the manifesto

announcing his accession to the throne he let it be very clearly

understood that he had no intention of limiting or weakening the

autocratic power that he had inherited from his ancestors. Nor did he

afterwards show any inclination to change his mind. All

the internal reforms that he initiated were intended to correct what he

considered as the too liberal tendencies of the previous reign, so that

he left behind him the reputation of a sovereign of the retrograde

type. In his opinion Russia was to be saved from anarchical disorders

and revolutionary agitation, not by the parliamentary institutions and

so-called liberalism of western Europe, but by the three principles that the elder generation of the Slavophils systematically recommended — nationality, Eastern Orthodoxy and autocracy.

His political ideal was a nation containing only one nationality, one

language, one religion and one form of administration; and he did his

utmost to prepare for the realization of this ideal by imposing the

Russian language and Russian schools on his German, Polish and other

non-Russian subjects (with the exception of the Finns), by fostering

Eastern Orthodoxy at the expense of other confessions, by persecuting

the Jews and

by destroying the remnants of German, Polish and Swedish institutions

in the outlying provinces. These policies were implemented by "May Laws" that banned Jews from rural areas and shtetls even within the Pale of Settlement. In

the other provinces he sought to counteract what he considered the

excessive liberalism of his father's reign. For this purpose he removed

what little power was wielded by the zemstvo, an elective local administration resembling the county and parish councils in England,

and placed the autonomous administration of the peasant communes under

the supervision of landed proprietors appointed by the government.

These came to be known as land captains,

who were much feared and resented amongst the peasant communities

throughout Russia. At the same time he sought to strengthen and

centralize the Imperial administration and to bring it more under his

personal control. In

foreign affairs he was emphatically a man of peace, but not at all a

partisan of the doctrine of peace at any price, and he followed the

principle that the best means of averting war is to be well prepared

for it. Though indignant at the conduct of Prince Bismarck towards

Russia, he avoided an open rupture with Germany, and even revived for a

time the Three Emperors' Alliance. It was only in the last years of his reign, when Mikhail Katkov had acquired a certain influence over him, that he adopted a more hostile attitude towards the cabinet of Berlin,

and even then he confined himself to keeping a large number of troops

near the German frontier, and establishing cordial relations with

France. With regard to Bulgaria he exercised similar self-control. The

efforts of Prince Alexander and afterwards of Stambolov to

destroy Russian influence in the principality excited his indignation,

but he persistently vetoed all proposals to intervene by force of arms. With encouragement from the successful assassination of his father, Alexander II, in 1881, the Peoples Will planned the murder of Tsar Alexander III. The plot was unsuccessful, one of the conspirators captured, Aleksandr Ulyanov,

was sentenced to death and hanged on 5 May 1887. Alexander Ulyanov was

the brother of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, who would later take the

pseudonym V.I. Lenin. The Emperor also survived the Borki train disaster of

1888. At the moment of the crash the royal family was in the dining

car. Its roof collapsed in the crash, and Alexander held the remains of

the roof on his shoulders as the children fled outdoors. The onset of

Alexander's kidney failure was later linked to the blunt trauma suffered at Borki. In Central Asian affairs he followed the traditional policy of gradually extending Russian domination without provoking a conflict with the United Kingdom (Panjdeh Incident),

and he never allowed the bellicose partisans of a forward policy to get

out of hand. As a whole his reign cannot be regarded as one of the

eventful periods of Russian history;

but it must be admitted that under his hard, unsympathetic rule the

country made considerable progress. Emperor Alexander and his

Danish-born wife regularly spent their summers in their Langinkoski manor near Kotka on the Finnish coast, where their children were immersed in a Scandinavian lifestyle of relative modesty. Alexander III became ill with nephritis in 1894, and died of this disease at the Livadia Palace on 1 November 1894. His remains were interred at the Peter and Paul Fortress in Saint Petersburg. He was succeeded by his eldest son Nicholas II of Russia. An equestrian statue of Tsar Alexander sculpted by Paolo Troubetzkoy once graced Znamenskaya Square in front of the Moscow Rail Terminal in St. Petersburg. It was later moved to the inner courtyard of the Marble Palace. Another memorial is located in the city of Irkutsk at the Angara embankment.