<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Étienne Bézout, 1730

- Painter John La Farge, 1835

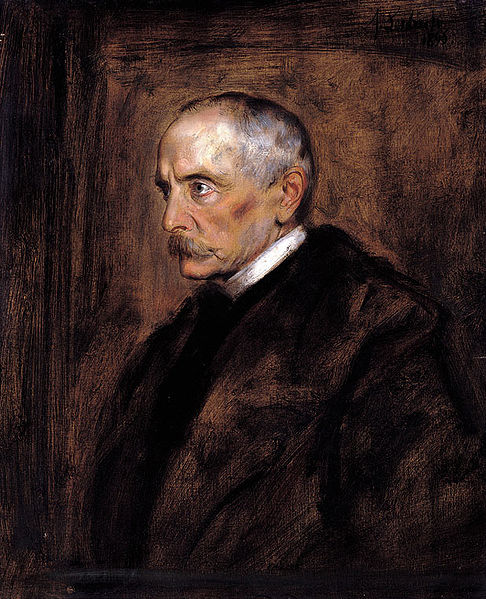

- Chancellor of Germany Chlodwig, Prince of Hohenlohe - Schillingsfürst, 1819

PAGE SPONSOR

Chlodwig Carl Viktor, Prince of Hohenlohe - Schillingsfürst, Prince of Ratibor and Corvey (German: Fürst zu Hohenlohe - Schillingsfürst, Fürst von Ratibor und Corvey) (31 March 1819 – 6 July 1901), usually referred to as the Prince of Hohenlohe, was a German statesman, who served as Chancellor of Germany and Prime Minister of Prussia from 1894 to 1900. Prior to his appointment as Chancellor, he had served in a number of other positions, including as Prime Minister of Bavaria (1866 – 1870), German Ambassador to Paris (1873 – 1880), Foreign Secretary (1880) and Imperial Lieutenant of Alsace - Lorraine (1885 – 1894). He was regarded as one of the most prominent liberal politicians of his time in Germany.

Chlodwig was born at Rotenburg an der Fulda, in Hesse, a member of the princely House of Hohenlohe. His father, Prince Franz Joseph (1787 – 1841), was a Catholic; his mother, Princess Konstanze of Hohenlohe - Langenburg, a Lutheran. In accordance with the compromise customary at the time, Chlodwig and his brothers were brought up in the religion of their father, while his sisters followed that of their mother.

As the younger son of a cadet line of his house it was necessary for Chlodwig to follow a profession. For a while he thought of obtaining a commission in the British army through the influence of his aunt, Princess Feodora of Hohenlohe - Langenburg, half-sister to Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. Instead, however, he decided to enter the Prussian diplomatic service. Chlodwig's application to be excused the preliminary steps, which involved several years' work in subordinate positions in the Prussian civil service, was refused by King Frederick William IV. As auscultator in the courts at Koblenz he acquired a taste for jurisprudence. He became a Referendar in September 1843, and after some months of travel in France, Switzerland and Italy he went to Potsdam as a civil servant 13 May 1844.

These

early years were invaluable, not only as giving him experience of

practical affairs but as affording him an insight into the strength and

weakness of the Prussian system. The immediate result was to confirm

his Liberalism. The Prussian principle of propagating enlightenment

with a stick did not appeal to him; he recognized the confusion and

want of clear ideas in the highest circles, the tendency to make

agreement with the views of the government the test of loyalty to the

state; and he noted in his journal (25 June 1844) four years before the

revolution of 1848, "a slight cause and we shall have a rising." "The

free press," he notes on another occasion, "is a necessity, progress

the condition of the existence of a state." If he was an ardent

advocate of German unity, and saw in Prussia the instrument for its

attainment, he was throughout opposed to the "Prussification" of

Germany. Chlodwig was the second of six sons. In 1834 his mother's brother-in-law Landgrave Viktor Amadeus of Hesse - Rotenburg died, leaving his estates to his nephews. It was not until 1840 that it was

determined how to divide these estates. On 15 October 1840 Chlodwig's

older brother, Viktor Moritz Karl zu Hohenlohe - Schillingsfürst,

1st Fürst von Corvey, (10 February 1818 - 30 January 1893),

renounced his rights as first-born son to the Principality of

Hohenlohe - Schillingsfürst, and was made Duke of Ratibor and Prince

of Corvey by King Frederick William IV of Prussia; at the same time Chlodwig received the additional title of Prince of Ratibor and Corvey. He also received the lordship of Treffurt in the Prussian governmental district of Erfurt. On

14 January 1841 Chlodwig's father, Fürst Franz Joseph (1787 – 1841),

died. As second son he ought to have succeeded as Prince (Fürst)

of Hohenlohe - Schillingsfürst, but instead he renounced his

rights

to his third brother Philipp Ernst, (24 May 1820 - 3 May 1845), with

the stipulation that they would revert to him in case of his brother's

death. On 3 May 1845 Philipp Ernst died, and Chlodwig succeeded as 7th

Prince of Hohenlohe - Schillingsfürst. As such he was an

hereditary member of the Upper House of the Bavarian Reichsrat. Such a

position

was incompatible with his political career in Prussia. On 18 April 1846

he took his seat as a member of the Bavarian Reichsrat, and the

following 26 June he received his formal discharge from the Prussian

service. Chlodwig's political life for the next eighteen years was generally uneventful. During the Revolution of 1848 his sympathies were with the Liberal idea of a united Germany, and he compromised his chances of favor from King Maximilian II of Bavaria by accepting the task of announcing to the courts of Rome, Florence and Athens the accession to office of the Archduke Johann of Austria as regent of Germany. In

general this period of Chlodwig's life was occupied in the management

of his estates, in the sessions of the Bavarian Reichsrat and in

travels. In 1856 he visited Rome, during which he noted the influence

of the Jesuits.

In 1859 he was studying the political situation at Berlin, and in the

same year he paid a visit to England. The marriage of his cadet brother, Konstantin Viktor Prinz zu Hohenlohe - Waldenburg - Schillingsfürst von Ratibor und Corvey, (8 September 1828 - Vienna, Austria, 14 February 1896), to Marie Antoinette Prinzessin zu Sayn - Wittgenstein - Berleburg, (18 February 1837 - 21 January 1920), on 15 October 1859 at Weimar, Germany led also to frequent visits to Vienna. Thus Chlodwig was brought into close touch with all the most notable people in Europe, including Catholic leaders of the Austrian Empire . At

the same time, during this period (1850 – 1866) he was endeavouring to

get into relations with the Bavarian government, with a view to taking

a more active part in affairs. Towards the German question his attitude

at this time was tentative. He had little hope of a practical

realization of a united Germany, and inclined towards the tripartite

divisions under Austria, Prussia and Bavaria the so-called Trias. He attended the Fürstentag at Frankfurt in 1863, and in the Schleswig - Holstein question was a supporter of the prince of Augustenburg. It was at this time that, at the request of Queen Victoria, he began to send her regular reports on the political condition of Germany. His portrait was painted by Philip de Laszlo. After the Austro - Prussian War of 1866 Chlodwig argued in the Bavarian Reichsrat for a closer union with mainly Protestant Prussia. King Ludwig II of Bavaria was opposed to any dilution of his power, but was eventually brought around, after Bismarck secretely bequeathed him a large sum from the Welfen - Funds (a large part of the fortune of the royal House of Hanover used after the annexation of Hannover by Prussia to fight Hannoverian loyalists) to pay off his large debts. On

31 December 1866 Chlodwig was appointed minister of the royal house and

of foreign affairs and president of the council of ministers. According

to Chlodwig's son Alexander (Denkwurdigkeiten, i. 178, 211) Chlodwig's appointment as Minister - President occurred at the instigation of the composer Richard Wagner. As

head of the Bavarian government Chlodwig's principal task was to

discover some basis for an effective union of the South German states

with the North German Confederation.

During the three critical years of his tenure of office he was, next to

Bismarck, the most important statesman in Germany. He carried out the

reorganization of the Bavarian army on the Prussian model, brought

about the military union of the southern states, and took a leading

share in the creation of the customs parliament (Zollparlament), of

which on the 28th of April 1868 he was elected a vice-president. During the agitation that arose in connection with the summoning of the First Vatican Council Chlodwig took up an attitude of strong opposition to the ultramontane position. In common with his brothers, the Duke of Ratibor and Cardinal Gustav Adolf zu Hohenlohe, he believed that the policy of Pope Pius IX of setting the Church in opposition to the modern state would prove ruinous to both, and that the definition of the dogma of papal infallibility would irrevocably commit the Church to the pronouncements of the Syllabus of Errors (1864). This view he embodied into a circular note to the Roman Catholic powers (9 April 1869), drawn up by Johann Joseph Ignaz von Döllinger,

inviting them to exercise the right of sending ambassadors to the

council and to combine to prevent the definition of the dogma. The

greater powers, however, were for one reason or another unwilling to

intervene, and the only practical outcome of Chlodwig's action was that

in Bavaria the powerful ultramontane party combined against him with

the Bavarian patriots who accused him of bartering away Bavarian

independence to Prussia. The combination was too strong for him; a bill

which he brought in for curbing the influence of the Church over

education was defeated, the elections of 1869 went against him, and in

spite of the continued support of the king he was forced to resign (7

March 1870). Though out of office, his personal influence continued to be very great both at Munich and Berlin,

in no small part due to the favorable terms of the treaty of the North

German Confederation with Bavaria, which embodied his views, and with

its acceptance by the Bavarian parliament. Elected a member of the

German Reichstag,

he was on 23 March 1871 chosen as one of its vice-presidents. He was

instrumental in founding the new groups which took the name of the

Liberal Imperial party (Liberale Reichspartei), the objects of which

were to support the new empire, to secure its internal development on

Liberal lines, and to oppose the Catholic Centre. Like his brother the Duke of Ratibor, Chlodwig was from the first a strenuous supporter of Bismarck's anti-papal policy (the Kulturkampf), the main lines of which (prohibition of the Society of Jesus, etc.) he himself suggested. Although he sympathized with the motives of the Old Catholics,

he did not join them, believing that the only hope for a reform of the

Church lay with those who desired it remaining in her communion. In

1872 Bismarck proposed appointing Chlodwig's younger brother Cardinal Gustav Adolf Prinz zu Hohenlohe - Schillingsfürst, (Rotenburg, Germany, 26 March 1823 - Rome, Italy, 30 October 1896), as Prussian envoy to the Holy See, but Pope Pius IX refused to receive him in this capacity. In

1873 Bismarck chose Chlodwig to succeed Count Harry Arnim as German

ambassador in Paris, where he remained for seven years. In 1878 he

attended the Congress of Berlin as third German representative. In 1880, after the death of the German Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Bernhard Ernst von Bülow (20 October 1879), Chlodwig was called to Berlin as temporary head of the Foreign Office and representative of Bismarck during his absence through illness. In 1885 Chlodwig was chosen to succeed Edwin Freiherr von Manteuffel as governor of Alsace - Lorraine,

incorporated after the 1870 war against France. In this capacity he had

to carry out the coercive measures introduced by Bismarck in 1887 and

1888, though he largely disapproved of them; his conciliatory

disposition, however, did much to reconcile the Alsace - Lorrainers to

German rule.

Chlodwig remained at Strasbourg till October 1894, when, at the urgent request of the Emperor William II, he consented, in spite of his advanced years, to accept the chancellorship as Caprivi's

successor. The events of his chancellorship belong to the general

history of Germany; as regards the inner history of this time the

editor of his memoirs has very properly suppressed the greater part of

the detailed comments which the prince left behind him. In general,

during his term of office, the personality of the chancellor was less

conspicuous in public affairs than in the case of either of his

predecessors. His appearances in the Prussian and German parliaments

were rare, and great independence was left to the secretaries of state. On 16 February 1847 at Rödelheim Chlodwig married Princess Marie of Sayn - Wittgenstein - Sayn, daughter of Ludwig Adolf Friedrich, 2nd Prince of Sayn - Wittgenstein - Sayn and his first wife Princess Caroline (Stephanie) Radziwill. Marie was the heiress to vast estates in Imperial Russia. This led to two prolonged visits to Verkiai, Lithuania, from 1851 to 1853 and again in 1860 in connection with the management of these properties. Chlodwig and Marie had six children.

Chlodwig resigned the chancellorship on 17 October 1900. He died at Bad Ragaz, Switzerland on 6 July 1901.