<Back to Index>

- Orientalist, Geologist and Physician Athanasius Kircher, 1602

- Decorator and Architect Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni, 1695

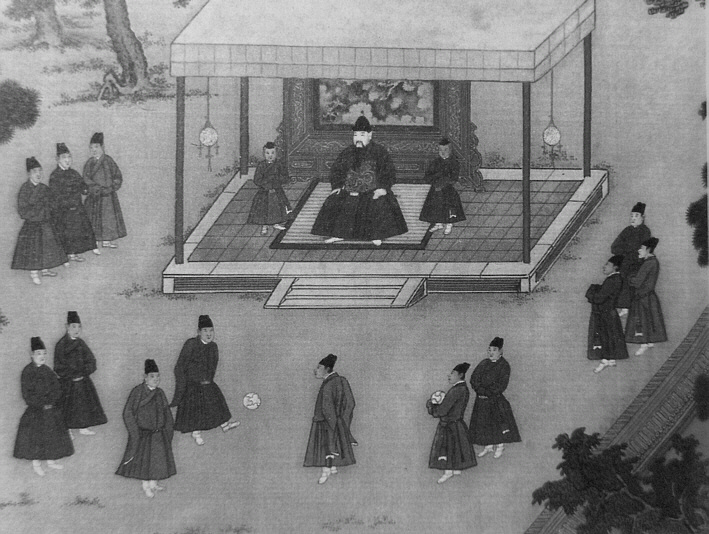

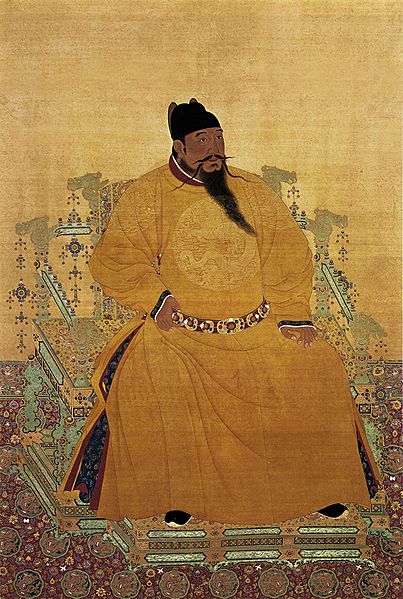

- Emperor of China Yongle, 1360

PAGE SPONSOR

The Yongle Emperor (Traditional Chinese: 永樂; Simplified Chinese: 永乐; pinyin: Yǒnglè) (May 2, 1360 – August 12, 1424), born Zhu Di (Chu Ti), was the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty of China from 1402 to 1424. His Chinese era name Yongle means "Perpetual Happiness".

He was the Prince of Yan (燕王), possessing a heavy military base in Beiping. He became known as Chengzu of Ming Dynasty (明成祖 also written Cheng Zu, or Ch'eng Tsu (Cheng Tsu) in Wade-Giles) after becoming emperor (self title). He became emperor by conspiring to usurp the throne which was against Hongwu Emperor's wishes. He moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing where it was located in the following generations, and constructed the Forbidden City there. After its dilapidation and disuse during the Yuan Dynasty and Hongwu's reign, the Yongle Emperor had the Grand Canal of China repaired

and reopened in order to supply the new capital of Beijing in the north

with a steady flow of goods and southern foodstuffs. He commissioned

most of the exploratory sea voyages of Zheng He. During his reign the monumental Yongle Encyclopedia was completed. Although his father Zhu Yuanzhang was reluctant to do so when he was emperor, Yongle upheld the civil service examinations for drafting educated government officials instead of using simple recommendation and appointment. The Yongle Emperor is buried in the Changling (長陵, "Long Mausoleum") tomb, the central and largest mausoleum of the Ming Dynasty Tombs. The Yongle Emperor was born Zhu Di on May 2, 1360, the fourth son of the new leader of the central Red Turbans, Zhu Yuanzhang, who would later rise to become the Hongwu Emperor,

the first emperor of the Ming Dynasty. Although Zhu Di would always

claim that his mother was the Empress Ma (Zhu Yuanzhang's primary

wife), his real birth mother is speculated by some to have been a

secondary queen consort of either Korean or Mongolian origin. Zhu

Di grew up as a prince in a loving, caring environment. His father

supplied nothing but the best education for his sons and eventually

gave them their own princedoms. Zhu Di was entitled as the Prince of

Yan, the area around Beijing. When Zhu Di moved to Beijing,

the city had been devastated by famine and disease and was under threat

of invasion from Mongolians from the north. The Mongolians had ruled

over Beijing, or Dadu, as it was then called, under the Yuan

Dynasty from 1271 to 1368, and had been expelled from the city by Zhu

Di's father, Zhu Yuangzhang, with the help of General Xu Da. Xu Da also helped Zhu Di, who was his son-in law, to secure the northern borders. Zhu

Di had been very successful against the Mongols and impressed his

father with his energy, risk taking ability and leadership. Even Zhu

Di's troops praised his effectiveness, especially when Emperor Hongwu

rewarded them for their service. But Zhu Di was not the oldest brother,

forcing his father to name Zhu Biao, the Prince of Jin, as the crown prince. When the Prince of Jin died of illness in 1392, worries of imperial succession ensued. The Hongwu Emperor died on June 24, 1398. His grandson Zhu Yunwen, the son of the late Zhu Biao, was crowned as the Jianwen Emperor. Zhu Di and Jianwen began a deadly feud. When Zhu Di traveled with his

guards to pay tribute to his father, Jianwen took his actions as a

threat and sent troops to repel him. Zhu Di was forced to leave in

humiliation. Jianwen persisted in refusing to let Zhu Di see his

father's tomb; Zhu Di challenged the emperor's judgment. Zhu Di quickly

became the biggest threat to the imperial court. Jianwen tried to avoid

direct contact with Zhu Di as much as possible. To achieve this, he

abolished the lesser princedoms to undermine Zhu Di's power and create

room in which to plant his own loyal generals. Zhu Di was soon

surrounded by Jianwen's generals, and cautiously reacted to the

political gridlock in which he found himself. His rebellion slowly began to take shape. Zhu

Di's leading rebellion slogan was self defense. This was enough to earn

him strong support from the populace and many supporting generals. He

was a great military commander and studied Sun Tzu's Art of War extensively.

He used surprise, deception, and caution and even questionable tactics

such as enlisting several Mongolian regiments to aid him in fighting

Jianwen. He defeated Li Jinglong,

a loyalist general, several times, deceiving him and overwhelming him

in many decisive battles. On January 15, 1402 Zhu Di made the bold

decision to march his army straight to Nanjing,

encountering stiff resistance. But his decision proved successful,

forcing an imperial retreat to protect the defenseless residence of

Jianwen. When Zhu Di reached the capital city, the frustrated and

disgraced General Li Jinglong opened the doors and permitted Zhu Di's

army to freely enter. In the wide spread panic caused by the sudden

entry, the emperor's palace caught fire. Jianwen and his wife

disappeared, most likely falling victim to the fire. Having

ended Jianwen's reign, Zhu Di and his administration spent the latter

part of 1402 brutally purging China of Jianwen's supporters. Such an

action was believed to be required to pacify China and maintain his

rule. He ordered all records of the four-year reign of Jianwen Emperor

to be dated as year 32 through year 35 of the Hongwu Emperor, in order to establish himself as the legitimate successor of the Hongwu Emperor. On

July 17, 1402, after a brief visit to his father's tomb, Zhu Di was

crowned Emperor Yongle at the age of 42. He would spend most of his

early years suppressing rumors, stopping bandits, and healing the

wounds of the land scarred by rebellion. Zhu

Di has been credited with ordering perhaps the only case of

"extermination of the ten agnates" (誅十族) in the history of China. For nearly 1500 years of feudal China, the Nine exterminations (誅九族) is considered one of the most severe punishments found in traditional Chinese law enforced until the end of Qing. The practice of exterminating the kin had been established since the Qin when Emperor Qin Shi Huang (reigned 247 BC – 221 BC) declared "Those who criticize the present with that of the past: Zu" (以古非今者族). Zu (族)

referred to the "extermination of three agnates" (三族): father, son and

grandson. The extermination was to ensure the elimination of challenges

to the throne and political enemies. Emperor Yang (reigned

604 – 617) extended it to the nine agnates. The nine agnates are the four

senior generations to the great-great-grandfather and four junior

generations to the great-great-grandson. The definition also included

siblings and cousins related to each of the nine agnates. Just before the accession of Emperor Yongle, prominent historian Fang Xiaoru (方孝孺) elicited the offense worthy of the "extermination of nine agnates" for refusing to write the inaugural address and

for insulting the Emperor. He was recorded as saying in defiance to the

would-be Emperor: "莫說九族,十族何妨!" ("Nevermind nine agnates, go ahead with

ten!"). Thus he was granted his wish with perhaps the only and infamous

case of "extermination of ten agnates" in the history of China. In

addition to the blood relations from his nine-agnates family hierarchy,

his students and peers were added to be the 10th group. Yongle

followed traditional rituals closely and remained superstitious. He did

not overindulge in the luxuries of palace life, but still used Buddhism and

Buddhist festivals to overcome some of the backwardness of the Chinese

frontier and to help calm civil unrest. He stopped the warring between

the various Chinese tribes and reorganized the provinces to best

provide peace within China. Due

to the stress and overwhelming amount of thinking involved in running a

post rebellion empire, Yongle searched for scholars to join his staff.

He had many of the best scholars chosen as candidates and took great

care in choosing them, even creating terms by which he hired people. He

was also concerned about the degeneration of Buddhism in China. In 1403, Yongle sent message, gifts, and envoys to Tibet inviting Deshin Shekpa, the fifth Gyalwa Karmapa of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, to visit China — apparently after having a vision of Avalokitesvara. After a long journey, Deshin Shekpa arrived in Nanjing on April 10, 1407 riding on an elephant towards the imperial palace, where tens of thousands of monks greeted him. He

convinced the emperor that there were different religions for different

people and that does not mean that one is better than the other. The

Karmapa was very well received in China and a number of miraculous

occurrences were reported. He also performed ceremonies for the

emperor's family. The emperor presented him with 700 measures of silver

objects and bestowed the title of 'Precious Religious King, Great

Loving One of the West, Mighty Buddha of Peace'. Aside

from the religious matters, the Emperor wished to establish an alliance

with the Karmapa similar to the one the Yuan (1277 – 1367) rulers had

established with the Sakyapa. He apparently offered to send armies to unify Tibet under the Karmapa but Deshin Shekpa refused this offer. Deshin left Nanjing on 17 May 1408. In 1410 he returned to Tsurphu where he had his monastery rebuilt which had been severely damaged by an earthquake. When it was time for him to choose an heir, Yongle very much wanted to choose his second son, Gaoxu.

Gaoxu was an athletic warrior type that contrasted sharply with his

older brother's intellectual and humanitarian nature. Despite much

counsel from his advisors, Yongle chose his older son, Gaochi (the

future Hongxi Emperor),

as his heir apparent mainly due to advice from Xie Jin. As a result,

Gaoxu became infuriated and refused to give up jockeying for his

father's favor and refusing to move to Yunnan province (of which he was prince). He even went so far as to undermine Xie Jin's council and eventually killed him. After Yongle's overthrow of Jianwen,

China's countryside was devastated. The fragile new economy had to deal

with low production and depopulation. Yongle laid out a long and

extensive plan to strengthen and stabilize the new economy, but first

he had to silence dissension. He created an elaborate system of censors

to remove corrupt officials from office that spread such rumors. Yongle

dispatched some of his most trusted officers to reveal or destroy

secret societies, Jianwen loyalists, and even bandits. To strengthen

the economy, he was forced to fight population decline by reclaiming

land, utilizing the most he could from the Chinese people, and

maximizing textile and agricultural production. Yongle also worked to reclaim production rich regions such as the Lower Yangtze Delta and called for a massive reconstruction of the Grand Canal of China.

During his reign, the Grand Canal was almost completely rebuilt and was

eventually moving imported goods from all over the world. Yongle's

short term goal was to revitalize northern urban centers, especially

his new capital at Beijing. Before the Grand Canal was rebuilt, grain

was transferred to Beijing in two ways; one route was simply via the East China Sea; the other was a far more laborious process of transferring the grain from large to small shallow barges (after passing the Huai River and having to cross southwestern Shandong), then transferred back to large river barges on the Yellow River before finally reaching Beijing. With the necessary tribute grain shipments of 4 million shi (one shi equal to 107 liters) to the north each year, both processes became incredibly inefficient. It was a magistrate of Jining, Shandong who sent a memorandum to Yongle protesting the current method of grain shipment, a wise request that Yongle ultimately granted. Yongle ambitiously planned to move China's capital to Beijing.

According to a popular legend, the capital was moved when the emperor's

advisers brought the emperor to the hills surrounding Nanjing and

pointed out the emperor's palace showing the vulnerability of the

palace to artillery attack. He

planned to build a massive network of structures in Beijing in which

government offices, officials, and the imperial family itself resided. After a painfully long construction time, the Forbidden City was finally completed and became the political capital of China for the next 500 years. Yongle sponsored and created many cultural traditions in China. He promoted Confucianism and

kept traditional ritual ceremonies with a rich cultural theme. His

respect for Chinese culture was apparent. He commissioned his Grand Secretary,

Xie Jin, to write a compilation of every subject and every known book

of the Chinese. The massive project's goal was to preserve Chinese

culture and literature in writing. The initial copy took 17 months to

transcribe and another copy was transcribed in 1557. The book, named the Yongle Encyclopedia, is still considered one of the most marvelous human achievements in history, despite it being gradually lost by time. Yongle's tolerance of Chinese ideas that did not agree with his own philosophies was well known. He treated Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism equally

(though he favored Confucianism). Strict Confucianists considered him

hypocritical, but his even handed approach helped him win the support

of the people and unify China. His love for Chinese culture sparked a sincere hatred for Mongolian culture. He considered it rotten and forbade the use of popular Mongolian names, habits, language, and clothing. Great lengths were taken by Yongle to eradicate Mongolian culture from China. Yongle called for the construction and repair of Islamic mosques during his reign. Two mosques were built by him, one in Nanjing and the other in Xi'an and they still stand today. Repairs were encouraged and the mosques were not allowed to be converted to any other use. Mongol invaders were still causing many problems for the Ming Dynasty. Yongle prepared to change this tradition. He mounted five military expeditions into Mongolia and crushed the remnants of the Yuan Dynasty that

had fled north after being defeated by Emperor Hongwu. He repaired the

northern defenses and forged buffer alliances to keep the Mongols at

bay in order to build an army. His strategy was to force the Mongols

into economic dependence on the Chinese and to launch periodic

initiatives into Mongolia to cripple their offensive power. He

attempted to compel Mongolia to

become a Chinese tributary, with all the tribes submitting and

proclaiming themselves vassals of the Ming, and wanted to contain and

isolate the Mongols. Through fighting, Yongle learned to appreciate the

importance of cavalry in battle and eventually began spending much of

his resources to keep horses in good supply. Yongle spent his entire

life fighting the Mongols. Failures and successes came and went, but it

should be noted that after Yongle's second personal campaign against

the Mongols, the Ming Dynasty was at peace for over seven years. Vietnam was

a significant source of difficulties during Yongle's reign. In 1406,

The Yongle Emperor responded to several formal petitions from members

of the (now deposed) Trần Dynasty,

however on arrival to Vietnam, both the Tran prince and the

accompanying Chinese ambassador were ambushed and killed. In response

to this insult the Yongle Emperor sent a huge army of 500,000 south to

conquer Vietnam. As the royal family were all executed by the Ho

monarchs Vietnam was integrated as a province of China, just as it had

been up until 939. With the Ho monarch defeated in 1407 the Chinese

began a serious and sustained effort to Sinicize the population. Unfortunately for the Chinese, their efforts to make Vietnam into a normal province

met with a significant resistance from the local population. Several

revolts started against the Chinese rulers. In early 1418 a major

revolt was begun by Lê Lợi, the future founder of the Lê Dynasty.

By the time the Yongle Emperor died in 1424 the Vietnamese rebels under

Lê Lợi's leadership had captured nearly the entire province. By

1427 the Xuande Emperor gave up the effort started by his grandfather and formally acknowledged Vietnam`s independence. As part of his desire to expand Chinese influence throughout the known world, Emperor Yongle sponsored the massive and long term Zheng He expeditions. While Chinese boats continued traveling to Japan, Ryukyu,

and many location in South-East Asia both before and after the Yongle

era, Zheng He's expeditions were China's only major sea-going

explorations of the world (although the Chinese may have been sailing to Arabia, East Africa, and Egypt since the Tang Dynasty, from AD 618 - 907). The first expedition was launched in 1405 (18 years before Henry the Navigator began Portugal's voyages of discovery). The expeditions were under the command of eunuch Zheng He and his associates (Wang Jinghong, Hong Bao, etc.). Seven expeditions were launched between 1405 and 1433, reaching major trade centers of Asia (as far as Tenavarai (Dondra Head), Hormuz and Aden) and north-eastern Africa (Malindi). Some of the boats used were apparently the largest sail-powered wooden boats in human history (National Geographic, May 2004). The Chinese expeditions were a remarkable technical and logistical achievement. Zhu Di's successors, the Hongxi Emperor and the Xuande Emperor,

felt that the costly expeditions were harmful to the Chinese state. The

Hongxi Emperor ended further expeditions and the descendants of the

Xuande Emperor suppressed much of the information about the Zheng He

voyages. In 1411, a smaller fleet, built in Jilin and commanded by another eunuch Yishiha, sailed down the Sungari and Amur Rivers. The expedition established a "Nurgal Regional Military Commission" (奴儿干都司, Nu'ergan Dusi) in the region, headquartered at the place the Chinese called Telin (特林) (now the village of Tyr, Russia). The local Nivkh or

Tungusic chiefs were granted ranks in the imperial administration.

Yishiha's expeditions returned to the lower Amur several more times

during the reigns of Yongle and Xuande, the last one visiting the region in the 1430s. After the death of Timur, who intended to invade China, the relations between the Yongle Emperor's China and Shakhrukh's

state in Persia and Transoxania state considerably improved, and the

countries exchanged large official delegations on a number of

occasions. Both the Chinese envoy to Samarkand and Herat, Chen Cheng, and his opposite party, Ghiyasu'd-Din Naqqah left detailed accounts of their visits to each other's country. One

of his wives was a Tungusic Jurchen (Nu chen) princess, which resulted

in many of the eunuchs serving him being of Jurchen origin.

On April 1, 1424, Yongle launched a large campaign into the Gobi Desert to chase a nuisance army of fleeting Tatars. Yongle became frustrated at his inability to catch up with his swift opponents and fell into a deep depression and then into illness (suffered

a series of minor strokes) . On August 12, 1424, the Yongle Emperor

died. He was entombed in Chang-Ling (長陵), a location northwest of

Beijing. Many have seen Yongle as in a life-long pursuit of power, prestige, and glory. He respected and worked hard to preserve Chinese culture by designing monuments such as the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing,

while undermining and cleansing Chinese society of foreign cultures. He

deeply admired and wished to save his father's accomplishments and

spent a lot of time proving his claim to the throne. His military

accomplishments and leadership are rivaled by only a handful of people

in world history. His reign was a mixed blessing for the Chinese

populace. Yongle's economic, educational, and military reforms provided

unprecedented benefits for the people, but his despotic style of government set

up spy agency. Despite these negatives, he is considered an architect

and keeper of Chinese culture, history, and statecraft and an

influential ruler in Chinese history. He may have suffered from undisclosed impotence in

his later life. He is remembered very much for his cruelty, just like

his father. He killed most of the Jian Wen palace servants, tortured

many Jianwen Emperor loyalists to death, killed or by other means badly

treated their relatives. His successor emperor freed most of them alive. In 1420, he ordered 2,800 ladies-in-waiting to a slow slicing death, and watched, because he thought one of his favourite Joseon concubine had been poisoned. However, unlike his father, he did not kill most of his generals, and he entrusted power to eunuchs like Zheng He,

with serious consequences for subsequent Ming emperors. He showed some

regrets over his cruelty, built the Yongle bell, but still had about

thirty beautiful women hanged to be buried with him after he died.