<Back to Index>

- Physician Ole Worm, 1588

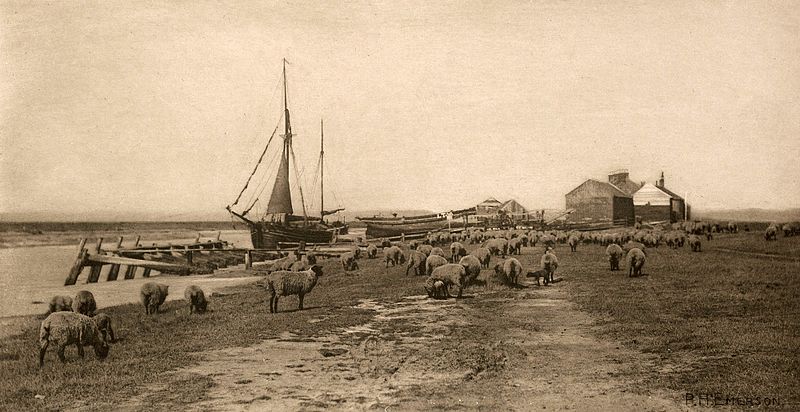

- Photographer Peter Henry Emerson, 1856

- Empress Consort of the Holy Roman Empire Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina, 1717

PAGE SPONSOR

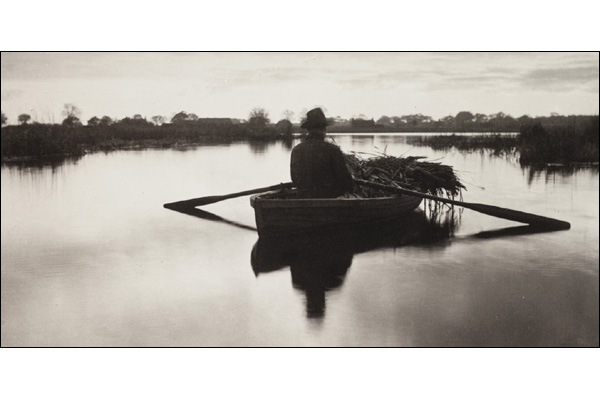

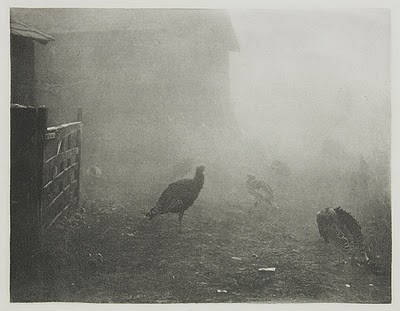

Peter Henry Emerson (May 1856 – 12 May 1936) was a British writer and photographer. His photographs are early examples of promoting photography as an art form. He is known for taking photographs that displayed natural settings and for his disputes with the photographic establishment about the purpose and meaning of photography.

Emerson was born in La Palma, Cuba, to an American father, Henry Ezekiel Emerson and a British mother, Jane, née Harris Billing. He was a distant relative of Samuel Morse and Ralph Waldo Emerson. His father was a sugar plantation owner in Cuba and Emerson spent his early years there. During the American Civil War he spent some time at Wilmington, Delaware, but moved to England in 1869, possibly after the death of his father. He was schooled at Cranleigh School where he was a noted scholar and athlete. He subsequently attended King's College London, before switching to Clare College, Cambridge, in 1879 where he earned his medical degree in 1885.

Emerson

was intelligent, well-educated and wealthy with a facility for clearly

articulating his many strongly held opinions. In 1881 he married Miss

Edith Amy Ainsworth and wrote his first book while on his honeymoon. The couple eventually had five children. Initially

influenced by naturalistic French painting, he argued for similarly

"naturalistic" photography and took photographs in sharp focus to

record country life as clearly as possible. His first album of

photographs, published in 1886, was entitled Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads,

and it consisted of 40 platinum prints that were informed by these

ideas. Before long, however, he became dissatisfied with rendering

everything in sharp focus, considering that the undiscriminating

emphasis it gave to all objects was unlike the way the human eye saw

the world. He

then experimented with soft focus, but was unhappy with the results

that this gave too, experiencing difficulty with accurately recreating

the depth and atmosphere which he saw as necessary to capture nature

with precision. Despite his misgivings, he took many photographs of landscapes and rural life in the East Anglian fenlands and published seven further books of his photography through the next ten years. In the last two of these volumes, On English Lagoons (1893) and Marsh Leaves (1895), Emerson printed the photographs himself using photogravure, after having bad experiences with commercial printers. After the publication of Marsh Leaves in

1895, generally considered to be his best work, Emerson published no

further photographs, though he continued writing and publishing books,

both works of fiction and on such varied subjects as genealogy and billiards. In 1924, he started writing a history of artistic

photography and completed the manuscript just before his death in Falmouth, Cornwall, on 12 May 1936. In 1979 he was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame. During

his life Emerson fought against the British photographic establishment

on a number of issues. In 1889 he published a controversial and

influential book Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art,

in which he explained his philosophy of art and straightforward

photography. The book was described by one writer as "the bombshell

dropped at the tea party" because of the case it made that truthful and

realistic photographs would replace contrived photography. This was a direct attack on the popular tradition of combining many photographs to produce one image that had been pioneered by O.G. Reijlander and Henry Peach Robinson in

the 1850s. Some of Robinson's photographs were of twenty or more

separate photographs combined to produce one image. This allowed the

production of images that, especially in early days, could not have

been produced indoors in low light, and it also made possible the

creation of highly dramatic images, often in imitation of allegorical

paintings. Emerson denounced this technique as false and claimed that

photography should be seen as a genre of its own, not one that seeks to

imitate other art forms. All Emerson's own pictures were taken in a single shot and without retouching,

which was another form of manipulation that he strongly disagreed with,

calling it "the process by which a good, bad, or indifferent photograph

is converted into a bad drawing or painting". Emerson

also believed that the photograph should be a true representation of

that which the eye saw. Following contemporary optical theories, he

produced photographs with one area of sharp focus while the remainder

was unsharp. He vehemently pursued this argument about the nature of

seeing and its representation in photography, to the discomfort of the

photographic establishment. Another

of Emerson's passionate beliefs was that photography was an art and not

a mechanical reproduction. An argument with the establishment ensued on

this point as well, but Emerson found that his defence of photography

as art failed, and he had to allow that photography was probably a form

of mechanical reproduction. The pictures the Robinson school produced

may have been "mechanical", but Emerson's may still be considered

artistic, since they were not faithful reproductions of a scene but

rather having depth as a result of his one-plane-sharp theory. When

he lost the argument over the artistic nature of photography, Emerson

did not publicise his photographic work but still continued to take

photographs.

He bought his first camera in 1881 or 1882 to be used as a tool on

bird watching trips with his friend, the ornithologist A.T. Evans. In 1885 he was involved in the formation of the Camera Club of London, and the following year he was elected to the Council of the Photographic Society and abandoned his career as a surgeon to become a photographer and writer. As well as his particular attraction to nature he was also interested in billiards, rowing and meteorology.