<Back to Index>

- Biologist Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov, 1845

- Composer Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi, 1567

- Mayor of Chicago Richard Joseph Daley, 1902

PAGE SPONSOR

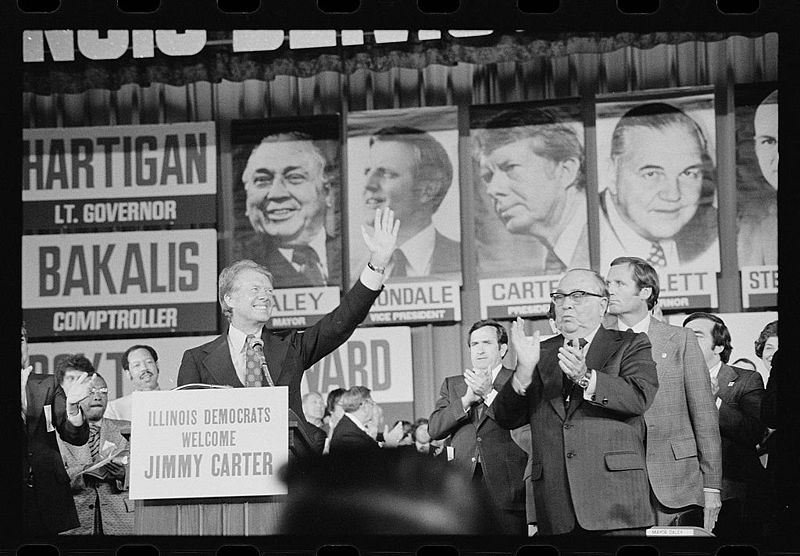

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) served for 21 years as the mayor and undisputed Democratic boss of Chicago and is considered by historians to be the "last of the big city bosses." He played a major role in the history of the Democratic Party, especially with his support of John F. Kennedy in 1960 and of Hubert Humphrey in 1968.

Daley was Chicago's third mayor in a row from the working class, heavily Irish American Bridgeport neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, and he lived there his entire life. Daley had two bases of power, serving as a Committeeman and Chairman of the Cook County Democratic

Central Committee from 1953, and as mayor of Chicago from 1955. He used

both positions until his death in 1976 to dominate party and civic

affairs. Daley's well-organized Democratic political machine was often accused of political corruption and

though many of Daley's subordinates were jailed, Daley was never

personally formally accused of corruption. He is remembered for doing

much to avoid the declines that some other "rust belt" cities like Cleveland, Buffalo and Detroit experienced during the same period. He had a strong base of support in Chicago's Irish Catholic community, and he was treated by national politicians such as Lyndon B. Johnson as a preeminent Irish American, with special connections to the Kennedy family. He is the second longest serving Chicago mayor in history. Richard M. Daley, his son, is the longest serving mayor of Chicago.

Richard J. Daley was born in Bridgeport,

a working class neighborhood of Chicago. He was the only child of

Michael and Lillian Daley, whose families had both arrived from the Old Parish area, near Dungarvan Co Waterford, Ireland during the Famine. Daley

would later state that his wellsprings were his religion, his family,

his neighborhood, the Democratic Party, and his love of the city. His father was a sheet metal worker with a reserved demeanor. Michael's

father, James E. Daley, was a butcher born in New York, while his

mother, Delia Gallagher Daley, was an Irish immigrant. Richard's mother

was outgoing and outspoken. Before women obtained the right to vote in

1920, Lillian Daley was an active Suffragette,

participating in marches. Mrs. Daley often brought her son to them. She

hoped her son's life would be more professionally successful than that

of his parents. Prior to his mother's death, Daley had won the

Democratic nomination for Cook County sheriff. Lillian Daley wanted

more than this for her son, telling a friend, "I didn't raise my son to

be a policeman."

Daley attended the elementary school of his parish, Nativity of Our Lord, and De La Salle Institute (where he learned clerical skills) and took night classes at DePaul University College of Law to earn a Juris Doctor in

1933. As a young man, his jobs included selling newspapers and making

deliveries for a door to door peddler; Daley worked at the stockyards

to pay his law school expenses. He spent the free time he had at the

Hamburg Athletic Club, a sports, social, and political organization

near his home. Hamburg and similar clubs were funded, at least in part,

by the Democratic machine politicians of the day. Daley made his mark

there, not in sports, but in organization as the club manager. At age

22 he was elected president of the club and served in that office until

1939. Daley,

though he practiced law with partner William J. Lynch, spent the

majority of his time dedicated to his career in politics.

Daley's career in politics began when he became a Democratic precinct captain; although he was a lifelong Democrat, Daley was first elected to the Illinois House of Representatives as a Republican in 1936. This was a matter of political opportunism and the peculiar setup for legislative elections in Illinois at the time, which allowed Daley to take the place on the ballot of the recently deceased Republican candidate David Shanahan. After his election, Daley quickly moved back to the Democratic side of the aisle in 1938, when he was elected to the Illinois State Senate. He was appointed by Governor Adlai Stevenson as head of the Illinois Department of Finance. Daley suffered his only political defeat in 1946, when he lost a bid to become Cook County sheriff. Daley then made a successful run for Cook County Clerk and held that position prior to being elected Chicago's mayor. In the late 1940s Daley became Democratic Ward Committeeman of the 11th Ward, a post he retained until his death.

First elected mayor in 1955 with a modest victory margin of 125,179 votes, Daley was re-elected to that office six times and had been mayor for 21 years at the time of his death. Through all those 21 years, the Illinois license plate on his car remained "125 179". During his administration, Daley ruled the city with an iron hand and dominated the political arena of the city and, to a lesser extent, that of the entire state.

Daley met Eleanor "Sis" Guilfoyle at a local ball game. He courted "Sis" for six years, during which time he finished law school and was established in his legal profession. They were married on June 17, 1936, and lived in a modest brick bungalow at 3536 South Lowe Avenue in the heavily Irish - American Bridgeport neighborhood, just blocks from his birthplace. They had three daughters and four sons, in that order. Their eldest son, Richard M. Daley, was elected mayor of Chicago in 1989. The youngest son, William M. Daley, was President Obama's White House Chief of Staff and formal US Secretary of Commerce under President Bill Clinton. Another son, John P. Daley, was a member of the Cook County Board of Commissioners. The other siblings have stayed out of public life. Michael Daley was a partner in the law firm Daley & George, and Patricia (Daley) Martino and Mary Carol (Daley) Vanecko were teachers, as was Eleanor, who died in 1998.

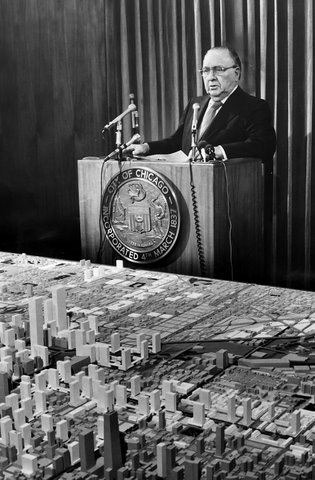

Major construction during his terms in office resulted in O'Hare International Airport, the Sears Tower, McCormick Place, the University of Illinois at Chicago campus, numerous expressways and subway construction projects, and other major Chicago landmarks. O'Hare was a particular point of pride for Daley, with him and his staff regularly devising occasions to celebrate it.

In 1966, Martin Luther King, Jr. confronted the Daley machine when King attempted to take the Civil Rights Movement north and encourage racial integration of Chicago's neighborhoods, such as Marquette Park.

Daley called for a "summit conference" and signed an agreement with

King and other community leaders to foster open housing. The agreement

was without legal standing and ignored. King's

efforts in Chicago were largely unsuccessful, and his failure in

Chicago was a serious setback for the Civil Rights Movement.

The year 1968 was a momentous year for Daley. In April, Daley was castigated by many for his sharp rhetoric in the aftermath of rioting that took place after Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination. Displeased with what he saw as an overly cautious police response to the rioting, Daley chastised police superintendent James B. Conlisk and subsequently related that conversation at a City Hall press conference as follows:

- "I said to him very emphatically and very definitely that an order be issued by him immediately to shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail in his hand, because they're potential murderers, and to shoot to maim or cripple anyone looting."

This statement generated significant controversy. Daley's supporters deluged his office with grateful letters and telegrams (nearly 4,500 according to Time Magazine), and it has been credited for Chicago's being one of the cities least affected by the riots. But others were appalled. Rev. Jesse Jackson, for example, called it "a fascist's response." The Mayor later backed away from his words in an address to the City Council, saying:

- "It is the established policy of the police department – fully supported by this administration – that only the minimum force necessary be used by policemen in carrying out their duties."

Later that month, Daley asserted "There wasn't any shoot-to-kill order. That was a fabrication."

In August, the 1968 Democratic National Convention was held in Chicago. Intended to showcase Daley's achievements to national Democrats and the news media, the proceedings during the convention instead garnered notoriety for the mayor and city.

With the nation divided by the Vietnam War and with the assassinations of King and Robert F. Kennedy earlier that year serving as backdrop, the city became a battleground for anti-war protesters who vowed to shut down the convention. In some cases, confrontations between protesters and police turned violent, with images of this violence broadcast on national television. Later, radical activists Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and three other members of the "Chicago Seven" were convicted of crossing state lines with the intent of inciting a riot as a result of these confrontations, though the convictions were overturned on appeal.

At the convention itself, Sen. Abraham A. Ribicoff (D-Conn.), went off-script during his speech nominating George McGovern, saying, "And with George McGovern as President of the United States, we wouldn’t have to have Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago." Ribicoff also tried to introduce a motion to shut down the convention and move it to another city. Many conventioneers applauded Ribicoff's remarks but an indignant Mayor Daley tried to shout down the speaker. As television cameras focused on Daley, lip-readers throughout America claimed to have observed him shouting, "Fuck you, you Jew son of a bitch." Defenders of the mayor would later claim that he was calling Ribicoff a faker., a charge denied by Daley and refuted by Mike Royko's reporting. A federal commission, led by local attorney and party activist Daniel Walker, later investigated the events surrounding the convention and described them as a "police riot." Daley's supporters challenged Walker's credibility because of his well-known opposition to Daley and Chicago machine politics.

During the 1969 Chicago Columbus Day Parade, Eco James Coli made headlines by walking the parade route next to Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley and Illinois Governor Richard Ogilvie. Both Daley and Ogilvie claimed ignorance of Coli's criminal background.

Despite a decline in popularity following 1968, Daley was historically re-elected for the fifth time in 1971. However, many have argued this was due to a lack of formidable opposition rather than Daley's own popularity.

In 1972, Democratic nominee George McGovern threw Daley out of the Democratic National Convention (replacing his delegation with one led by Jesse Jackson). This event arguably marked a downturn in Daley's power and influence within the Democratic Party but, given his public standing, McGovern later made amends by putting Daley loyalist (and Kennedy in-law) Sargent Shriver on his ticket.

On December 20, 1976, Daley suffered a massive heart attack while visiting his doctor's office and died at the age of 74. His services and funeral Mass took place in the church he attended from his childhood, Nativity of Our Lord. He is buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Worth Township, southwest of Chicago.

Daley

was known by many Chicagoans as "Da Mare" ("The Mayor"), "Hizzoner"

("His Honor"), and "The Man on Five" (his office was on the fifth floor

of City Hall). Since Daley's death and the subsequent election of son Richard as

mayor in 1989, the first Mayor Daley has become known as "Boss Daley,"

"Old Man Daley," or "Daley Senior" to residents of Chicago.

In 1939, Illinois State Senator William "Botchy" Connors remarked

"you couldn't give that guy a nickel, that's how honest he is."

However, in January 1973, former Illinois Racing Board Chairman William S. Miller testified that Daley had "induced" him to bribe Illinois Governor Otto Kerner. This scandal marked the start of two years of controversy where the integrity of the Mayor and his office was strongly questioned.

Daley,

who never lost his blue-collar Chicago accent (better known as a

southside Chicago accent), was known for often mangling his syntax and

other verbal gaffes. Daley made one of his most memorable verbal

missteps in 1968, while defending what the news media reported as

police misconduct during that year's violent Democratic Convention. "Gentlemen, get the thing straight once and for all – the policeman isn't there to create disorder, the policeman is there to preserve disorder."

Known for shrewd party politics, Daley was a stereotypical machine politician, and his Chicago Democratic Machine, based on control of thousands of patronage positions, was instrumental in bringing a narrow 8,000 vote victory in Illinois for John F. Kennedy in 1960. A PBS documentary entitled "Daley" explained that Mayor Daley, JFK, and LBJ potentially stole the 1960 election by stuffing ballot boxes in Texas and rigging the vote in Chicago. In addition, it reveals, Daley withheld many votes from certain wards when the race seemed close.

Daley was usually open with the news media, meeting with them for frequent news conferences, and taking all questions — if not answering all of them. According to columnist and biographer Mike Royko, Daley got along better with editors and publishers than with reporters.

Daley had limited opposition among the 50 aldermen of the Chicago City Council. For the most part, the aldermen supported Daley and the official party position consistently, except for a small number of Republicans from the German wards on the northwest side of the city and a small number of independents (a group that grew during Daley's mayoralty to represent groups that felt disenfranchised by Daley's policies).

Daley's

chief means of attaining electoral success was his reliance on local

precinct captains, who marshaled and delivered votes on a neighborhood by neighborhood basis. Many of these precinct captains

held patronage jobs with the city, mostly minor posts at low pay. Each

ward had a ward leader in charge of the precinct captains, some of whom

were corrupt. The notorious First Ward (encompassing downtown, which

had many businesses but few residents) was tied to the local mafia or crime syndicate, but Daley's own ward was supposedly clean and his personal honesty was never questioned successfully.

A poll of 160 historians, political scientists and urban experts ranked Daley as the sixth best mayor in American history. Daley's ways may not have been democratic, but his defenders have argued that he got positive things done for Chicago which a non-boss would have been unable to do. While detractors point out that he did nothing to integrate what had then become known as the most segregated city in the nation, others argue that he was acting on behalf of his constituency, who did not want an integrated Chicago.

On the 50th anniversary of Daley's first 1955 swearing-in, several dozen Daley biographers and associates met at the Chicago Historical Society. Historian Michael Beschloss called Daley "the pre-eminent mayor of the 20th century." Chicago journalist Elizabeth Taylor said, "Because of Mayor Daley, Chicago did not become a Detroit or a Cleveland." Many feel that by revitalizing the downtown area and firmly fixing the middle class in place in the city limits, Daley probably did save Chicago from declining to the extent of the average Rust Belt city. Robert Remini pointed out that while other cities were in fiscal crisis in the 1960s and 1970s, "Chicago always had a double-A bond rating."

According to Chicago folksinger Steve Goodman, "no man could inspire more love, more hate."

Aside from the obvious legacy of having an effect on the city of Chicago for twenty-one years as its mayor, Daley is memorialized specifically in the following:

- A week after his death, one of the City Colleges of Chicago was renamed as the Richard J. Daley College in his honor.

- The Richard J. Daley Center is a 32-floor office building completed in 1965 and renamed for the mayor after his death.

- The Richard J. Daley Library at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

- Richard J. Daley Park immediately east of Millennium Park and north of Grant Park

- There is a critically acclaimed play about Daley, "Hizzoner: Daley the First" now playing at the Beverly Arts Center.

- The Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young song "Chicago" (written by Graham Nash) was about the 1968 Democratic convention. In their Four Way Street live album, Nash ironically dedicates the song to "Mayor Daley."

- In a scene set at the Chez Paul restaurant in the 1980 film The Blues Brothers, the Maître d' (Alan Rubin) is seen talking on the phone: "No, sir, Mayor Daley no longer dines here, sir. He's dead, sir." Later in the film, when the brothers are driving rapidly through Chicago, Elwood (Dan Aykroyd) comments "If my estimations are correct, we are approximately ten minutes from the Honorable Richard J. Daley Center." "That's where they got that Picasso!" Jake enthuses. The classic "use of excessive force in the apprehension of the Blues Brothers has been approved" line delivered by a police dispatcher is an obvious homage to Daley's 1968 order during the riots following Martin Luther King's assassination.