<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Gerrit Mannoury, 1867

- Actor Jean Gabin (Jean Alexis Moncorgé), 1904

- Welsh Pirate Bartholomew Roberts (Black Bart), 1682

PAGE SPONSOR

Bartholomew Roberts (17 May 1682 – 10 February 1722), born John Roberts, was a Welsh pirate who raided ships off America and West Africa between 1719 and 1722. He was the most successful pirate of the Golden Age of Piracy, capturing far more ships than some of the best known pirates of this era such as Blackbeardor Captain Kidd. He is estimated to have captured over 470 vessels. He is also known as Black Bart (Welsh: Barti Ddu), but this name was never used in his lifetime, and also risks confusion with Black Bart of the American West.

Bartholomew Roberts was born in 1682 in Casnewydd-Bach, or Little Newcastle, between Fishguard and Haverfordwest in Pembrokeshire, Wales. His name was originally John Roberts, and his father was most likely George Roberts. It's not clear why Roberts changed his name from John to Bartholomew, but pirates often adopted aliases, and he may have chosen that name after the well known buccaneer Bartholomew Sharp. He is thought to have gone to sea when he was 13 in 1695 but there is no further record of him until 1718, when he was mate of a Barbados sloop. In 1719 he was third mate on the slave ship Princess of London, under Captain Abraham Plumb. In early June that year the Princess was anchored at Anomabu, then spelled Annamaboa, which is situated along the Gold Coast of West Africa (present day Ghana), when she was captured by pirates. The pirates were in two vessels, the Royal Rover and the Royal James, and were led by captain Howell Davis. Davis, like Roberts, was a Welshman, originally from Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire. Several of the crew of the Princess of London were forced to join the pirates, including Roberts. Davis quickly discovered Roberts' abilities as a navigator and took to consulting him. He was also able to confide to Roberts information in Welsh, thereby keeping it hidden from the rest of the crew. Roberts is said to have been reluctant to become a pirate at first, but soon came to see the advantages of this new lifestyle. Captain Charles Johnson reports him as saying:

“ In an honest service there is thin commons, low wages, and hard labour. In this, plenty and satiety, pleasure and ease, liberty and power; and who would not balance creditor on this side, when all the hazard that is run for it, at worst is only a sour look or two at choking? No, a merry life and a short one shall be my motto. ”

It is easy to understand the lure of piracy; in the merchant navy, Roberts' wage was less than £3 per month and he had no chance of promotion to captaincy.

A few weeks later the Royal James had to be abandoned because of worm damage. The Royal Rover headed for the Isle of Princes, now Príncipe. Davis hoisted the flags of a British man-of-war, and was allowed to enter the harbour. After a few days Davis invited the governor to lunch on board his ship, intending to hold him hostage for a ransom. As Davis had to send boats to collect the governor, he was invited to call at the fort for a glass of wine first. The Portuguese had by now discovered that their visitors were pirates, and on the way to the fort Davis' party was ambushed and Davis himself shot dead.

A new captain now had to be elected. Davis' crew was divided into "Lords" and "Commons", and it was the "Lords" who had the right to propose a name to the remainder of the crew. Within six weeks of his capture, Roberts was elected captain. This was an unusual move since he was openly against his even being on board the vessel, and was probably due to his navigational abilities and his demeanor, which history reflects was outspoken and opinionated. According to Johnson:

“ He accepted of the Honour, saying, that since he had dipp'd his Hands in Muddy Water, and must be a Pyrate, it was better being a Commander than a common Man. ”

His first act as captain was to lead the crew back to Príncipe to avenge the death of Captain Davis. Roberts and his crew sprang onto the island in the darkness of night, killed a large portion of the male population, and stole all items of value that they could carry away. Soon afterwards he captured a Dutch Guineaman, then two days later an English ship called the Experiment. While the ship took on water and provisions at Anamboe, a vote was taken on whether the next voyage should be to the East Indies or to Brazil. The vote was for Brazil.

The

combination of bravery and success that marked this adventure cemented

most of the crew's loyalty to Roberts. They concluded that he was

"pistol proof" and that they had much to gain by staying with him. Roberts and his crew crossed the Atlantic and watered and boot topped their

ship on the uninhabited island of Ferdinando. They then spent about

nine weeks off the Brazilian coast, but saw no ships. They were about

to leave for the West Indies when they encountered a fleet of 42 Portuguese ships in the Todos os Santos' Bay, waiting for two men-of-war of 70 guns each to escort them to Lisbon.

Roberts took one of the vessels, and ordered her master to point out

the richest ship in the fleet. He pointed out a ship of 40 guns and a

crew of 170, which Roberts and his men boarded and captured. The ship

proved to contain 40,000 gold moidores and jewelry including a cross

set with diamonds, designed for the King of Portugal. The Rover now headed for Devil's Island off

the coast of Guiana to spend the booty. A few weeks later they headed

for the River Surinam, where they captured a sloop. When a brigantine was sighted, Roberts took forty men to pursue it in the sloop, leaving Walter Kennedy in command of the Rover.

The sloop became wind-bound for eight days, and when Roberts and his

men were finally able to return, they discovered that Kennedy had

sailed off with the Rover and what remained of the loot. Roberts and his crew renamed their sloop the Fortune and agreed on new articles, which they swore on a Bible to uphold. The Fortune now headed northwards towards Newfoundland. After raiding Canso, Nova Scotia and capturing a number of ships around Cape Breton and

the Newfoundland banks, Roberts raided the harbour of Ferryland,

capturing a dozen vessels. On 21 June he attacked the larger harbour of Trepassey,

sailing in with black flags flying. All the ships in the harbour were

abandoned by their panic stricken captains and crews, and the pirates

were masters of Trepassey without any resistance being offered. Roberts

had captured 22 ships, but was angered by the cowardice of the captains

who had fled their ships. Every morning when a gun was fired, the

captains were forced to attend Roberts on board his ship; they were

told that anyone who was absent would have his ship burnt. One brig from Bristol was taken over by the pirates to replace the sloop Fortune and

fitted out with 16 guns. When the pirates left in late June, all the

other vessels in the harbour were set on fire. During July, Roberts

captured nine or ten French ships and commandeered one of them, fitting

her with 26 cannons and changing her name to the Good Fortune.

With this more powerful ship, the pirates captured many more vessels

before heading south for the West Indies, accompanied by Montigny la

Palisse's sloop, which had rejoined them. In September 1720 the Good Fortune was careened and repaired at the island of Carriacou before being renamed the Royal Fortune, the first of several ships to be given this name by Roberts. In late September the Royal Fortune and the Fortune headed

for the island of St. Christopher's, and entered Basse Terra Road

flying black flags and with their drummers and trumpeters playing. They

sailed in among the ships in the Road, all of which promptly struck

their flags. The

next landfall was at the island of St. Bartholomew, where the French

governor allowed the pirates to remain for several weeks to carouse. By

25 October they were at sea again, off St. Lucia, where they captured up to 15 French and English ships in the next three days. Among the captured ships was the Greyhound, whose chief mate, James Skyrme, joined the pirates. He would later become captain of Roberts' consort, the Ranger. During

this time Roberts caught the Governor of Martinique promptly hanging

him on the yardarm of his flagship, The Royal Fortune. By the spring of 1721, Roberts' depredations had almost brought seaborne trade in the West Indies to a standstill. The Royal Fortune and the Good Fortune therefore set sail for West Africa. On 20 April Thomas Anstis, the commander of the Good Fortune, left Roberts in the night and continued to raid shipping in the Caribbean. The Royal Fortune continued towards Africa. By late April, Roberts was at the Cape Verde islands. The Royal Fortune was found to be leaky, and was abandoned here. The pirates transferred to the Sea King, which was renamed the Royal Fortune. The new Royal Fortune made

landfall off the Guinea coast in early June, near the mouth of the

Senegal River. Two French ships, one of 10 guns and one of 16 guns,

gave chase, but were captured by Roberts. Both these ships were

commandeered. One, the Comte de Toulouse, was renamed the Ranger, while the other was named the Little Ranger and used as a storeship. Thomas Sutton was made captain of the Ranger and James Skyrme captain of the Little Ranger. Roberts now headed for Sierra Leone, arriving on 12 June. Here he was told that two Royal Navy ships, HMS Swallow and HMS Weymouth, had left at the end of April, planning to return before Christmas. On 8 August he captured two large ships at Point Cestos, now River Cess in Liberia. One of these was the frigate Onslow, transporting soldiers bound for Cape Coast (Cabo

Corso) Castle. A number of the soldiers wished to join the pirates and

were eventually accepted, but as landlubbers were given only a quarter share. The Onslow was converted to become the fourth Royal Fortune. In November and December the pirates careened their ships and relaxed at Cape Lopez and the island of Annobon. Sutton was replaced by Skyrme as captain of the Ranger. They captured several vessels in January 1722, then sailed into Ouidah harbour with black flags flying. All the eleven ships at anchor there immediately struck their colours. On 5 February HMS Swallow, commanded by Captain Chaloner Ogle, came upon the three pirate ships, the Royal Fortune, the Ranger and the Little Ranger careening at Cape Lopez. The Swallow veered away to avoid a shoal, making the pirates think that she was a fleeing merchant ship. The Ranger, commanded by James Skyrme, departed in pursuit. Once out of earshot of the other pirates, the Swallow opened her gun ports and an engagement began.

Ten of the pirates were killed and Skyrme had his leg taken off by a

cannon ball, but refused to leave the deck. Eventually, the Ranger was forced to strike her colours and the surviving crew were captured. On 10 February, the Swallow returned to Cape Lopez and found the Royal Fortune still there. On the previous day, Roberts had captured the Neptune, and many of his crew were drunk and unfit for duty just when he needed them most. At first, the pirates thought that the approaching ship was the Ranger returning, but a deserter from the Swallow recognized her and informed Roberts while he was breakfasting with Captain Hill, the master of the Neptune. As he usually did before action, he dressed himself in his finest clothes: The pirates' plan was to sail past the Swallow,

which meant exposing themselves to one broadside. Once past, they would

have a good chance of escaping. However, the helmsman failed to keep the Royal Fortune on the right course, and the Swallow was able to approach to deliver a second broadside. Captain Roberts was killed by grapeshot,

which struck him in the throat while he stood on the deck. Before his

body could be captured by Ogle, Roberts' wish to be buried at sea was

fulfilled by his crew, who weighed his body down and threw it overboard

after wrapping it in his ship's sail. It was never found. Roberts'

death shocked the pirate world, as well as the British Navy. The local

merchants and civilians had thought him invincible, and some considered

him a hero. Roberts' death was seen by many historians as the end of

the Golden Age of Piracy. His death is now commemorated by a celebration known as The Blackest Day, marking the day in which the Golden Age of Piracy came to an end. The battle continued for another two hours, until the Royal Fortune's

mainmast fell and the pirates signalled for quarter. One member of the

crew, John Philips, tried to reach the magazine with a lighted match to

blow up the ship, but was prevented by two forced men. Only three

pirates, including Roberts, had been killed in the battle. A total of

272 men had been captured by the Royal Navy. Of these, 75 were black,

and these were sold into slavery. The remainder, apart from those who

died on the voyage back, were taken to Cape Coast Castle. 54 were

condemned to death, of whom 52 were hanged and two reprieved. Another

twenty were allowed to sign indentures with the Royal African Company; Burl comments that they "exchanged an immediate death for a lingering one". Seventeen

men were sent to the Marshalsea prison in London for trial, while over

a third of the total were acquitted and released. Of the captured pirates who gave their place of birth, 42% were from Cornwall, Devon and Somerset and

another 19% from London. There were smaller numbers from northern

England and from Wales, and another quarter from a variety of countries

including Ireland, Scotland, the West Indies, the Netherlands and

Greece. After

problems with mutinous Irishmen early in his pirate career, Roberts was

known to generally avoid recruiting Irishmen, to the extent that

captured merchant sailors would sometimes affect an Irish accent to

discourage Roberts from forcing them into his pirate crew. Captain Chaloner Ogle was rewarded with a knighthood, the only British naval officer to be honoured specifically for his actions against pirates. He also profited financially, taking gold dust from Roberts' cabin, and eventually became an Admiral. According to Cordingly, this battle was to prove a turning point in the war against the pirates. Cawthorne considers the death of Roberts to mark the end of the 'golden age of piracy', while Rediker comments: Most of the information on Roberts comes from the book A General History of the Pyrates, published a few years after Roberts' death. The original 1724 title page credits one Captain Charles Johnson as the author. (The book is often printed under the byline of Daniel Defoe, on the assumption that "Charles Johnson" is a pseudonym,

but there is no proof Defoe is the author, and the matter remains in

dispute.) Johnson devotes more space to Roberts than to any of the

other pirates in his book, describing him as: After his exploits in Newfoundland the Governor of New England commented that "one cannot with-hold admiration for his bravery and courage". He

hated cowardice, and when the crews of 22 ships in Trepassey harbour

fled without firing a shot he was angry at their failure to defend

their ships. Roberts

was the archetypal pirate captain in his love of fine clothing and

jewelry, but had some traits unusual in a pirate, notably a preference

for drinking tea rather than rum. He is often described as a teetotaler and a Sabbatarian,

but there is no proof of this. He certainly disliked drunkenness while

at sea, but Johnson does not state that he was a teetotaller and

implies that he drank beer. The claim that he was a Sabbatarian is based on the article stating that

the musicians were not obliged to play on Sundays, but this may merely

have been intended to ensure the musicians a day's rest, as they were

obliged to play music whenever the crew demanded it of them on other

days. Ironically, Roberts' final defeat was facilitated by the

drunkenness of his crew. Black Bart was not as cruel to prisoners as some pirates, such as Edward Low, but did not treat them as well as did Howell Davis or Edward England. Johnson says that he would sometimes ill-use prisoners if he felt that the crew demanded it, but: Roberts

sometimes gave cooperative captains and crew of captured ships gifts,

such as pieces of jewelry or items of captured cargo. In 1997, the claim was put forward in Women Pirates and the Politics of the Jolly Roger,

edited by Gabriel Kuhn and Tyler Austin, that Bartholomew Roberts was a

female transvestite. It was argued that Roberts' corpse was thrown

overboard to conceal this fact. The book did not explain why, if

Roberts were a woman, "she" would draw up articles that provided the

death penalty for bringing a woman aboard in disguise, which would have

led to "her" own death had "she" been discovered. Other than the

disposal of Roberts' body, no evidence was produced to support the

thesis, and it has not been accepted by the majority of nautical

historians. Whatever the truth of Roberts' gender, he could not

possibly have been Anne Bonny in disguise, as some supporters of the thesis have claimed. Bonny was aboard Calico Jack Rackham's sloop, cruising off Jamaica in October 1720, at the same time that Roberts, on the Royal Fortune, was in the mid-Atlantic trying to reach the Cape Verde islands.

In late February 1720 they were joined by the French pirate Montigny la Palisse in another sloop, the Sea King. The inhabitants of Barbados equipped two well armed ships, the Summerset and the Philipa, to try to put an end to the pirate menace. On 26 February they encountered the two pirate sloops. The Sea King quickly fled, and after sustaining considerable damage the Fortune broke off the engagement and was able to escape. Roberts headed for Dominica to repair the sloop, with twenty of his crew dying of their wounds on the voyage. There were also two sloops from Martinique out

searching for the pirates, and Roberts swore vengeance against the

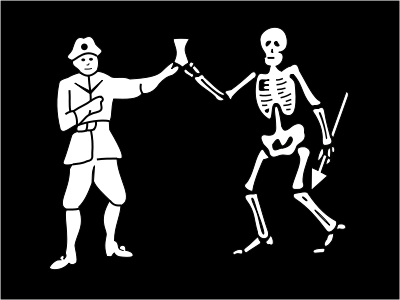

inhabitants of Barbados and Martinique. He had a new flag made with a

drawing of himself standing upon 2 skulls, one labelled ABH (A

Barbadian's Head) and the other AMH (A Martiniquian's Head).

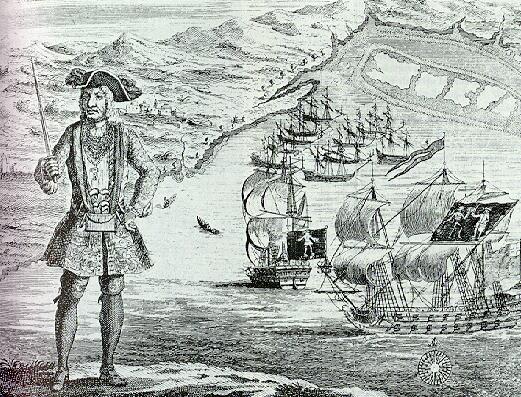

“ Roberts himself made a gallant figure, at the time of the engagement,

being dressed in a rich crimson damask waistcoat and breeches, a red

feather in his hat, a gold chain round his neck, with a diamond cross

hanging to it, a sword in his hand, and two pairs of pistols slung over

his shoulders ... ”

Captain Chaloner Ogle claimed to have missed out on the treasure which the pirates had left on the Little Ranger when they sailed to their last engagement with the Swallow. Ogle did admit having taken possession of the lesser loot from the Ranger and Royal Fortune; the crew did not receive their share until Ogle was reluctantly forced

to give it to them by the legal system three years later. By the time

Ogle and his men arrived to take the treasure in the Little Ranger, it had gone - with Captain Hill of the Neptune. Several weeks after the defeat of Bartholemew Roberts, however, Captain Ogle and Captain Hill had both sailed across the Atlantic and were in Port Royal at

the same time. Even if this is assumed to be a coincidence, it seems

nearly inconceivable that Captain Ogle, who was already swindling his

own crew, would not have then confronted Captain Hill, who Ogle could

easily have had hanged for trading with pirates, at least

theoretically. It therefore seems likely that the larger part of

Bartholemew Roberts's treasure ended up in the hands of Captain Ogle,

and some part of it in the hands of Captain Hill.“ The defeat of Roberts and the subsequent eradication of piracy off the coast of Africa represented a turning point in the slave trade and even in the larger historys of capitalism. ”

“ ...

a tall black [i.e. dark complexioned] Man, near forty Years of Age ...

of good natural Parts, and personal Bravery, tho' he apply'd them to

such wicked Purposes, as made them of no Commendation, frequently

drinking 'Damn to him who ever lived to wear a Halter'. ” “ When

he found that rigour was not expected from his people (for he often

practised it to appease them), then he would give strangers to

understand that it was pure inclination that induced him to a good

treatment of them, and not any love or partiality to their persons;

"For", says he, "there is none of you but will hang me, I know,

whenever you can clinch me within your power." ”