<Back to Index>

- Physicist Mihajlo Idvorski Pupin, 1858

- Etcher Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1720

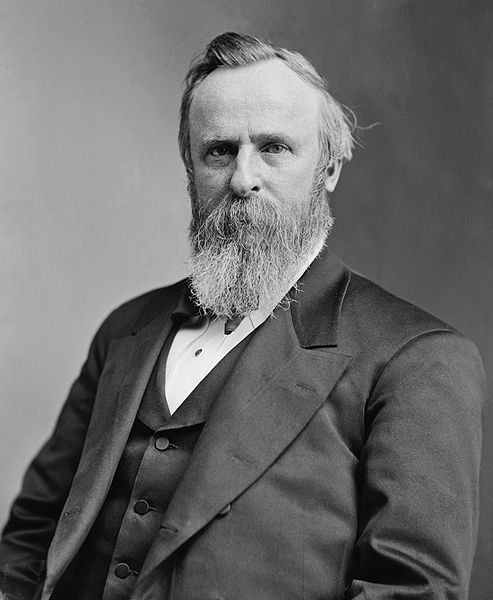

- 19th President of the United States Rutherford Birchard Hayes, 1822

PAGE SPONSOR

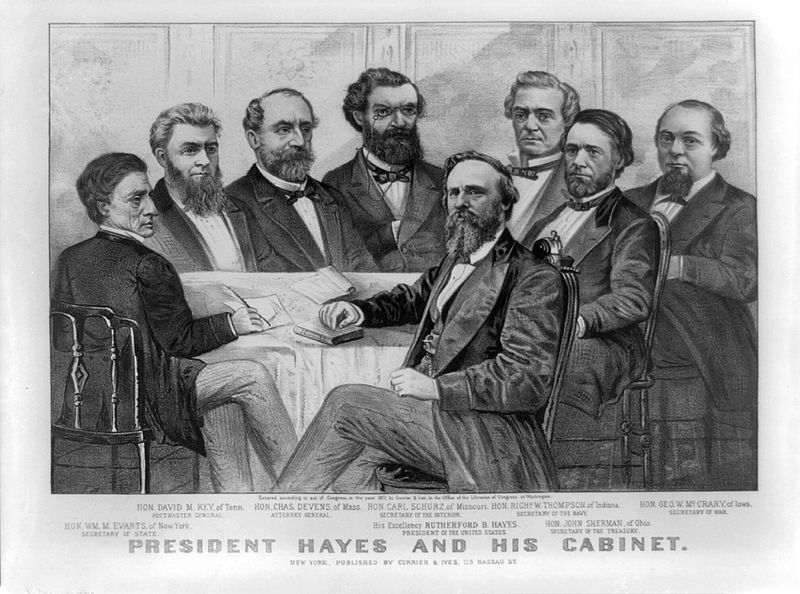

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th President of the United States, serving one term from 1877 to 1881. As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution. Hayes was a reformer who began the efforts that would lead to civil service reform and attempted, unsuccessfully, to reconcile the divisions that had led to the American Civil War fifteen years earlier.

Born in Delaware, Ohio, Hayes practiced law in Lower Sandusky (now Fremont) and was city solicitor of Cincinnati from 1858 to 1861. When the Civil War began, Hayes left a successful political career to join the Union Army. Wounded five times, most seriously at the Battle of South Mountain, he earned a reputation for bravery in combat and was promoted to the rank of major general. After the war, he served in the U.S. Congress from 1865 to 1867 as a Republican. Hayes left Congress to run for Governor of Ohio and was elected to two terms, serving from 1867 to 1871. After his second term had ended, he resumed the practice of law for a time, but returned to politics in 1875 to serve a third term as governor. In 1876, Hayes was elected president in one of the most contentious and hotly disputed elections in American history. Although he lost the popular vote to Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, Hayes won the presidency by the narrowest of margins after a Congressional commission awarded him twenty disputed electoral votes. The result was the Compromise of 1877, in which the Democrats acquiesced to Hayes's election and Hayes accepted the end of military occupation of the South. Hayes believed in meritocratic government, equal treatment without regard to race, and improvement through education. He ordered federal troops to quell the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and ordered them out of Southern capitals as Reconstruction ended. He implemented modest civil service reforms that laid the groundwork for further reform in the 1880s and 1890s. Hayes kept his pledge not to run for re-election. He retired to his home in Ohio and became an advocate of social and education reform.

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was born in Delaware, Ohio, on October 4, 1822, the son of Rutherford Hayes and Sophia Birchard. Hayes's father, a Vermont storekeeper, took the family to Ohio in 1817 but died ten weeks before his son's birth. Sophia

took charge of the family, bringing up Hayes and his sister, Fanny, the

only two of her four children to survive to adulthood. She never remarried. Sophia's younger brother, Sardis Birchard, lived with the family for a time. Always close to Hayes, Sardis Birchard became a father figure to him, contributing to his early education. Through both his father and mother, Hayes was of New England colonial ancestry. His earliest American ancestor emigrated to Connecticut from Scotland in 1625. Hayes's great-grandfather, Ezekiel Hayes, was a militia captain in Connecticut in the American Revolutionary War, but Ezekiel's son (Hayes's grandfather, also named Rutherford) left his New Haven home during the war for the relative peace of Vermont. His

mother's ancestors arrived in Vermont at a similar time, and most of

his close relatives outside Ohio would continue to live there. John Noyes, an uncle by marriage, had been his father's business partner in Vermont and was later elected to Congress. His first cousin, Mary Jane Noyes Mead, was the mother of sculptor Larkin Goldsmith Mead and architect William Rutherford Mead. John Humphrey Noyes, the founder of the Oneida Community, was also a first cousin. Hayes attended the common schools in Delaware, Ohio, and enrolled in 1836 at the Methodist Norwalk Seminary in Norwalk, Ohio. He did well at Norwalk, and the following year transferred to a preparatory school in Middletown, Connecticut, where he studied Latin and Ancient Greek. Returning to Ohio, Hayes entered Kenyon College in Gambier in 1838. He enjoyed his time at Kenyon, and was successful scholastically; while there, he joined several student societies and became interested in Whig politics. He graduated with highest honors in 1842 and addressed the class as its valedictorian. After briefly reading law in Columbus, Ohio, Hayes moved east once more to attend Harvard Law School in 1843. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1845 and opened his own law office in Lower Sandusky (now Fremont). Business

was slow at first, but he gradually attracted a few clients and also

represented his uncle Sardis in real estate litigation. In 1847, Hayes became ill with what his doctor thought to be tuberculosis. Thinking a change in climate would help, he considered enlisting in the Mexican – American War, but on his doctor's advice he instead visited family in New England. Returning from there, Hayes and his uncle Sardis made another long journey to Texas, where Hayes visited with Guy M. Bryan, a Kenyon classmate and distant relative. Business remained meager on his return to Lower Sandusky, and Hayes decided to move to Cincinnati. Hayes moved to Cincinnati in 1850, and opened a law office with John W. Herron, a lawyer from Chillicothe. Later, Herron joined a more established firm and Hayes formed a new partnership with William K. Rogers and Richard M. Corwine. Hayes found business better in Cincinnati, and enjoyed the social attractions of the larger city, joining the Cincinnati Literary Society and the Odd Fellows Club. He also attended the Episcopal Church in Cincinnati but did not become a member. Hayes courted his future wife, Lucy Webb, during his time there. His

mother had encouraged him to get to know Lucy years earlier, but Hayes

had believed she was too young and focused his attention on other women. Four

years later, Hayes began to spend more time with Lucy. They became

engaged in 1851 and married on December 30, 1852, at the house of

Lucy's mother. Over the next five years, Lucy gave birth to three sons: Birchard Austin (1853), Webb Cook (1856), and Rutherford Platt (1858). Lucy, a Methodist, teetotaler, and abolitionist, influenced her husband's views on those issues, although he never formally joined her church. Hayes

had begun his law practice dealing primarily with commercial cases but

won greater prominence in Cincinnati as a criminal defense attorney, defending several people accused of murder. In one, he used a form of the insanity defense that saved the accused from the gallows, confining her instead to a mental institution. Hayes found his services requested to defend escaped slaves accused under the recently passed Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. As Cincinnati was just across the Ohio River from Kentucky,

a slave state, many such cases were tried in its courts. A staunch

abolitionist, Hayes found his work on behalf of fugitive slaves

personally gratifying as well as politically useful, as it raised his

profile in the newly formed Republican party. His political reputation rose with his professional plaudits. Hayes declined the Republican nomination for a judgeship in 1856. Two

years later, some Republicans proposed Hayes to fill a vacancy on the

bench and he considered accepting the appointment until the office of city solicitor also became vacant. The

city council elected Hayes to fill the vacancy, and he won a full

two-year term from the voters in April 1859 with a larger majority than

other Republicans on the ticket. As the Southern states began to secede after Lincoln's election to the Presidency in 1860, Hayes was lukewarm on the idea of a civil war to restore the Union. Considering that the two sides might be irreconcilable, he suggested that the Union "[l]et them go." Although

Ohio had voted for Lincoln in 1860, the Cincinnati voters turned

against the Republican party after secession, and the Democrats and Know - Nothings combined to sweep the city elections in April 1861, ejecting Hayes from the city solicitor's office. Hayes formed a new law partnership with Leopold Markbreit and returned to private practice. After the Confederates had fired on Fort Sumter, Hayes resolved his doubts and joined a volunteer company composed of his Literary Society friends. That June, Governor William Dennison appointed several of the officers of the volunteer company to positions in the 23rd Regiment of Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Hayes was promoted to major, and his friend and college classmate Stanley Matthews was appointed lieutenant colonel; also joining the regiment as a private was another future president, William McKinley. After a month of training, Hayes and the 23rd Ohio set out for western Virginia in July 1861 as a part of the Kanawha Division. They passed the next few months out of contact with the enemy until September, when the regiment encountered Confederates at Carnifex Ferry in present day West Virginia and drove them back. In

November, Hayes was promoted to lieutenant colonel (Matthews having

been promoted to colonel of another regiment) and led his troops deeper

into western Virginia, where they entered winter quarters. The

division resumed its advance the following spring, and Hayes led

several raids against the rebel forces, on one of which he sustained a

minor injury to his knee. That September, Hayes's regiment was called east to reinforce General John Pope's Army of Virginia at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Although Hayes and his troops did not arrive in time for the battle, they joined the Army of the Potomac as it hurried north to cut off Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, which was advancing into Maryland. Marching north, the 23rd was the lead regiment encountering the Confederates at the Battle of South Mountain on September 14. Hayes led a charge against an entrenched position and was shot through his left arm, fracturing the bone. The regiment continued on to Antietam, but Hayes was out of action for the rest of the campaign. In October, he was promoted to colonel and assigned to command of the first brigade of the Kanawha Division as a brevet brigadier general. The division spent the following winter and spring near Charleston, Virginia (present day West Virginia), out of contact with the enemy. Hayes saw little action until July 1863, when the division skirmished with John Hunt Morgan's cavalry at the Battle of Buffington Island. Returning

to Charleston for the rest of the summer, Hayes spent the fall

encouraging the men of the 23rd Ohio to re-enlist, and many did so. In 1864, the Army command structure in West Virginia was reorganized, and Hayes's division was assigned to George Crook's Army of West Virginia. Advancing into southwestern Virginia, they destroyed Confederate salt and lead mines there. On May 9, they engaged Confederate troops at Cloyd's Mountain, where Hayes and his men charged the enemy entrenchments and drove the rebels from the field. Following the rout, the Union forces destroyed Confederate supplies and skirmished with the enemy again successfully. Hayes and his brigade moved to the Shenandoah Valley for the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Crook's corps was attached to Major General David Hunter's Army of the Shenandoah and soon back in contact with Confederate forces, capturing Lexington, Virginia on June 11. They continued south toward Lynchburg, tearing up railroad track as they advanced. Hunter believed the troops at Lynchburg were too powerful, however, and Hayes and his brigade returned to West Virginia. Hayes thought that Hunter lacked aggression, writing in a letter home that "General Crook would have taken Lynchburg." Before the army could make another attempt, Confederate General Jubal Early's raid into Maryland forced their recall to the north. Early's army surprised them at Kernstown on July 24, where Hayes was slightly wounded from a bullet to the shoulder. Hayes also had a horse shot out from under him, and the army was defeated. Retreating into Maryland, the army was reorganized again, with Major General Philip Sheridan replacing Hunter. By August, Early was retreating down the valley, with Sheridan in pursuit. Hayes's troops fended off a Confederate assault at Berryville and advanced to Opequon Creek, where they broke the enemy lines and pursued them farther south. They followed up the victory with another at Fisher's Hill on September 22, and one more at Cedar Creek on October 19. At

Cedar Creek, Hayes sprained his ankle after being thrown from a horse

and was struck in the head by a spent round, which did not cause

serious damage. Hayes's conduct drew the attention of his superiors, with Ulysses S. Grant later

writing of Hayes that "[h]is conduct on the field was marked by

conspicuous gallantry as well as the display of qualities of a higher

order than that of mere personal daring." Cedar Creek marked the end of the campaign. Hayes was promoted to brigadier general in October 1864 and brevetted major general. Around this time, Hayes learned of the birth of another son, George Crook

Hayes. The army went into winter quarters once more, and in spring 1865

the war quickly came to a close with Lee's surrender to Grant at

Appomattox. Hayes visited Washington, D.C. that May and observed the Grand Review of the Armies, after which he and the 23rd Ohio returned to their home state to be mustered out of the service.

While serving in the Army of the Shenandoah in 1864, Hayes received the Republican nomination to the House of Representatives from Ohio's 2nd congressional district. Asked

by friends in Cincinnati to leave the army to campaign, Hayes refused,

saying that an "officer fit for duty who at this crisis would abandon

his post to electioneer for a seat in Congress ought to be scalped." Instead,

Hayes wrote several letters to the voters explaining his political

positions and was elected by a 2,400-vote majority over the incumbent

Democrat, Alexander Long. When the 39th Congress assembled

in December 1865, Hayes was sworn in as a part of a large Republican

majority. Hayes identified with the moderate wing of the party, but was

willing to vote with the radicals for the sake of party unity. The major legislative effort of the Congress was the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, for which Hayes voted and which passed both houses of Congress in June 1866. Hayes's beliefs were in line with his fellow Republicans on Reconstruction issues: that the South should be restored to the Union, but not without adequate protections for black southerners. President Andrew Johnson,

to the contrary, wanted to readmit the seceded states quickly without

first ensuring that they adopted laws protecting the newly freed

slaves' civil rights and granted pardons to many of the leading former

Confederates. Hayes, along with congressional Republicans, disagreed. They worked to reject Johnson's vision of Reconstruction and to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Re-elected in 1866, Hayes returned to the lame duck session to vote for the Tenure of Office Act, which ensured that Johnson could not remove administration officials without the Senate's consent. He also voted for a civil service reform bill that attracted the votes of many reform minded Republicans, but did not pass. Hayes continued to vote with the majority in the 40th Congress on the Reconstruction Acts, but resigned in July 1867 to campaign for governor. A

popular Congressman and former soldier, Hayes was considered by Ohio

Republicans to be an excellent standard bearer for the 1867 election

campaign. Hayes's

political views were more moderate than the Republican party's

platform, although he agreed with the proposed amendment to the Ohio

state constitution that would guarantee suffrage to black Ohioans. Hayes's opponent, Allen G. Thurman, made the proposed amendment the centerpiece of the campaign, and both

men campaigned vigorously, making speeches across the state, mostly

focusing on the suffrage question. The election was mostly a disappointment to Republicans, as the amendment failed to pass and Democrats gained a majority in the state legislature. Hayes

thought at first that he, too, had lost, but the final tally showed

that he had won the election by 2,983 votes of 484,603 votes cast. As a Republican governor with a Democratic legislature, Hayes had a limited role in governing, especially since Ohio's governor had no veto power.

Despite the restrictions of the office, Hayes used his office to

oversee the establishment of a school for deaf-mutes and a reform

school for girls. He also endorsed the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson and urged his conviction, which failed by one vote in the United States Senate. Nominated

for a second term in 1869, Hayes campaigned once more for equal rights

for black Ohioans and sought to associate his Democratic opponent, George H. Pendleton with disunion and racism. Hayes was re-elected with an increased majority, and the Republicans took the legislature, ensuring Ohio's ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guaranteed black suffrage. With

a Republican legislature, Hayes's second term was more enjoyable, and

he was gratified to see suffrage expanded and a state Agricultural and

Mechanical College (later to become Ohio State University) established. He also proposed a reduction in state taxes and reform of the state prison system. Choosing not to seek re-election, Hayes looked forward to retiring from politics in 1872.

As

Hayes prepared to leave office, several delegations of reform minded

Republicans urged him to run against the incumbent Republican, John Sherman, for United States Senate. Hayes declined the offers, preferring to preserve party unity and retire to private life. Hayes

especially looked forward to spending time with his children, two of

whom (daughter Fanny and son Scott) had been born in the past five

years. Initially,

Hayes tried to promote railway extensions to his hometown, Fremont, and

spent the rest of his time managing some real estate he had acquired in Duluth, Minnesota. Not entirely removed from politics, Hayes held out some hope of a cabinet appointment,

but was disappointed to receive only an appointment as assistant U.S.

treasurer at Cincinnati, which he turned down. He also allowed himself to be nominated for his old House seat in 1872 but was not disappointed when he lost the election to Henry B. Banning, a fellow Kenyon College alumnus. Lucy gave birth to another son, Manning Force Hayes, in 1873. That same year, the Panic of 1873 hurt business prospects across the nation, including Hayes's. Sardis Birchard died that year and the Hayes family moved into Spiegel Grove, the grand house Birchard had built with them in mind. Hayes

hoped to remain out of politics in order to pay off the debts he had

incurred during the Panic, but when the Republican state convention

nominated him for governor in 1875, he accepted. The campaign against Democratic nominee William Allen focused primarily on Protestant fears of the possibility of state aid to Catholic schools. Hayes was against such funding and, while he was not known to be personally anti-Catholic, he allowed anti - Catholic fervor to contribute to the enthusiasm for his candidacy. The campaign was a success, and Hayes was returned to the governorship by a 5,544 vote majority. Hayes's

success in Ohio immediately elevated him to the top ranks of Republican

politicians under consideration for the presidency in 1876. The Ohio delegation to the 1876 Republican National Convention was united behind him, and Senator John Sherman did all in his power to bring Hayes the nomination. In June 1876, the convention assembled with James G. Blaine of Maine as the favorite. Blaine

started with a significant lead in the delegate count but could not

muster a majority. As he failed to gain votes, the delegates looked

elsewhere for a nominee and settled on Hayes on the seventh ballot. The convention then selected Representative William A. Wheeler of New York for Vice President, a man about whom Hayes had recently asked "I am ashamed to say: who is Wheeler?" The Democratic nominee was Samuel J. Tilden, the Governor of New York. Tilden was considered a formidable adversary who, like Hayes, had a reputation for honesty. Also like Hayes, Tilden was a hard money man and supported civil service reform. The

campaign, in accordance with the custom of the time, was conducted by

surrogates, with Hayes and Tilden remaining in their respective home

towns. The poor economic conditions made the party in power unpopular and made Hayes suspect that he might lose the election. Both candidates focused their attention on the swing states of New York and Indiana, as well as the three southern states — Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida — where Reconstruction governments still ruled. The

Republicans emphasized the danger of letting Democrats run the nation

so soon after southern Democrats provoked the Civil War and, to a

lesser extent, the danger a Democratic administration would pose to the

recently won civil rights of southern blacks. Democrats, for their part, trumpeted Tilden's record of reform and contrasted it with the corruption of the incumbent Grant administration. As

the returns were tallied on election day, it was clear that the race

was close: Democrats had carried most of the South, as well as New York, Indiana, Connecticut, and New Jersey. The popular vote also favored Tilden, but Republicans realized that if they held the three unredeemed southern states together with some of the western states, they would emerge with an electoral college majority. On November 10, three days after election day, Tilden appeared to have won 184 electoral votes: one short of a majority. Hayes appeared to have 165 votes, with the 19 votes of Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina still in doubt. Because

of fraud by both parties in the three disputed states, the results were

uncertain, and Republicans and Democrats both claimed victories there. To further complicate matters, one of the three electors from Oregon (a state Hayes had won) was disqualified, reducing Hayes's total to 164. If either candidate could claim the 20 disputed votes, he would be elected president. There

was considerable debate about which person or house of Congress was

authorized to decide between the competing slates of electors, with the

Republican Senate and the Democratic House each claiming priority. By January 1877, with the question still unresolved, Congress agreed to submit the matter to a bipartisan Electoral Commission, which would be authorized to determine the fate of the disputed electoral votes. The Commission was to be made up of five representatives, five senators, and five Supreme Court justices. To ensure partisan balance, there would be seven Democrats and seven Republicans, with Justice David Davis, an independent respected by both parties, being the fifteenth member. The balance was upset when Democrats in the Illinois legislature elected

Davis to the Senate, hoping to sway his vote. Davis disappointed

Democrats, however, by refusing to serve on the Commission on account

of his election to the Senate. As all of the remaining Justices were Republicans, Justice Joseph P. Bradley, believed to be the most independent minded of them, was selected to take Davis's place on the Commission. The

Commission met in February and the eight Republicans voted to award all

20 electoral votes to Hayes. Democrats were outraged by the result and

attempted a filibuster to prevent Congress from accepting the Commission's findings. As the March 4 inauguration day neared, Republican and Democratic Congressional leaders met at Wormley's Hotel in Washington to negotiate a compromise.

Republicans promised that, in exchange for Democratic acquiescence in

the Committee's decision, Hayes would withdraw federal troops from the

South and accept the election of Democratic governments in the last of

the unredeemed South. The Democrats agreed, and the filibuster was ended. Hayes was elected, but Reconstruction was finished.

Because March 4, 1877 fell on a Sunday, Hayes took the oath of office privately on Saturday, March 3, in the Red Room of the White House. He took the oath publicly on the following Monday on the East Portico of the United States Capitol. In

his inaugural address, Hayes attempted to soothe the passions of the

past few months, saying that "he serves his party best who serves his

country best". He pledged to support "wise, honest, and peaceful local self-government" in the South, as well as reform of the civil service and a full return to the gold standard. Despite

his message of conciliation, many Democrats never considered Hayes's

election legitimate and referred to him as "Rutherfraud" or "His

Fraudulency" for the next four years. Hayes had been a firm supporter of Republican Reconstruction policies

throughout his political career, but the first major act of his

presidency was an end to Reconstruction and the return of the South to

home rule. Even

without the conditions of the Wormley's Hotel agreement, Hayes would

have been hard-pressed to continue the policies of his predecessors.

The House of Representatives in the 45th Congress was controlled by a Democratic majority that refused to appropriate enough funds for the army to continue to garrison the South. Even among Republicans, devotion to continued military Reconstruction was fading. Only

two states were still under Reconstruction's sway when Hayes assumed

the Presidency and, without troops to enforce the voting rights laws,

these too soon fell. Hayes's

later attempts to protect the rights of southern blacks were

ineffective, as were his attempts to rebuild Republican strength in the South. He did, however, defeat Congress's efforts to curtail federal power to monitor federal elections. Democrats in Congress passed an army appropriation bill in 1879 with a rider that repealed the Force Acts. Those

Acts, passed during Reconstruction, made it a crime to prevent someone

from voting because of his race. Hayes was determined to preserve the

law protecting black voters, and he vetoed the appropriation. The

Democrats did not have enough votes to override the veto, but they

passed a new bill with the same rider. Hayes vetoed this as well, and

the process was repeated three times more. Finally,

Hayes signed an appropriation without the offensive rider, but Congress

refused to pass another bill to fund federal marshals, who were vital

to the enforcement of the Force Acts. The election laws remained in effect, but the funds to enforce them were curtailed for the time being. Hayes next attempted to reconcile the social mores of

the South with the recently passed civil rights laws by distributing

patronage among southern Democrats. "My task was to wipe out the color

line, to abolish sectionalism, to end the war and bring peace," he

wrote in his diary. "To do this, I was ready to resort to unusual

measures and to risk my own standing and reputation within my party and the country." All

of his efforts were in vain; Hayes failed to convince the South to

accept the idea of racial equality and failed to convince Congress to

appropriate funds to enforce the civil rights laws. Hayes took office determined to reform the system of civil service appointments, which had been based on the spoils system since Andrew Jackson was president. Instead of giving federal jobs to political supporters, Hayes wished to award them by merit according to an examination that all applicants would take. Immediately, Hayes's call for reform brought him into conflict with the Stalwart,

or pro-spoils, branch of the Republican party. Senators of both parties

were accustomed to being consulted about political appointments and

turned against Hayes. Foremost among his enemies was New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, who fought Hayes's reform efforts at every turn. To show his commitment to reform, Hayes appointed one of the best known advocates of reform, Carl Schurz, to be Secretary of the Interior and asked Schurz and William M. Evarts, his Secretary of State, to lead a special cabinet committee charged with drawing up new rules for federal appointments. John Sherman, the Treasury Secretary, ordered John Jay to investigate the New York Custom House, which was stacked with Conkling's spoilsmen. Jay's

report suggested that the New York Custom House was so overstaffed with

political appointments that 20% of the employees were expendible. Although he could not convince Congress to outlaw the spoils system, Hayes issued an executive order that

forbade federal office holders from being required to make campaign

contributions or otherwise taking part in party politics. Chester A. Arthur, the Collector of the Port of New York, and his subordinates Alonzo B. Cornell and George H. Sharpe, all Conkling supporters, refused to obey the president's order. In

September 1877, Hayes demanded the three men's resignations, which they

refused to give. Nonetheless, he submitted appointments of Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., L. Bradford Prince, and Edwin Merritt — all supporters of Evarts, Conkling's New York rival — to the Senate for confirmation as their replacements. The

Senate's Commerce Committee, which Conkling chaired, voted unanimously

to reject the nominees, and the full Senate rejected Roosevelt and

Prince by a vote of 31 – 25, confirming Merritt only because Sharpe's

term had expired. Hayes was forced to wait until July 1878 when, during a Congressional recess, he sacked Arthur and Cornell and replaced them by recess appointments of Merritt and Silas W. Burt, respectively. Conkling

opposed the appointees' confirmation when the Senate reconvened in

February 1879, but Merritt was approved by a vote of 31 – 25, as was Burt

by 31 – 19, giving Hayes his most significant civil service reform

victory. For the remainder of his term, Hayes pressed Congress to enact permanent reform legislation, even using his last annual message to

Congress on December 6, 1880 to appeal for reform. While reform legislation did not pass during Hayes's presidency, his advocacy

provided "a significant precedent as well as the political impetus for

the Pendleton Act of 1883," which was signed into law by President Chester Arthur.

In his first year in office, Hayes was faced with the United States' largest labor disturbance to date: the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. In

order to make up for financial losses suffered since the panic of 1873,

the major railroads cut their employees' wages several times in 1877. In July of that year, workers from the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad walked off the job in Martinsburg, West Virginia to protest their reduction in pay. The strike quickly spread to workers of the New York Central, Erie, and Pennsylvania railroads, with the strikers soon numbering in the thousands. Fearing a riot, Governor Henry M. Mathews asked

Hayes to send federal troops to Martinsburg, and Hayes did so, but when

the troops arrived there was no riot, only a peaceful protest. In Baltimore, however, a riot did erupt on July 20 and Hayes ordered the troops at Fort McHenry to assist the governor in its suppression; by the time they arrived, the riot had dispersed. Pittsburgh next exploded into riots, but Hayes was reluctant to send in troops without the governor first requesting them. Other discontented citizens joined the railroad workers in rioting. After

a few days, he resolved to send in troops to protect federal property

wherever it appeared to be threatened and gave Major General Winfield Scott Hancock overall command of the situation, marking the first use of federal troops to break a strike against a private company. The riot spread further, to Chicago and St. Louis, where strikers shut down railroad facilities. By July 29, the riots had ended and federal troops returned to their barracks. Although

no federal troops had killed any of the strikers, or been killed

themselves, clashes between state militia troops and strikers resulted

in deaths on both sides. The

railroads were victorious in the short term, as the workers returned to

their jobs and some wage cuts remained in effect, but the public blamed

the railroads for the strikes and violence, and they were compelled to

improve working conditions and attempted no further cuts. Business

leaders praised Hayes, but his own opinion was more equivocal; as he

recorded in his diary: "The strikes have been put down by force; but now for the real remedy.

Can't something [be] done by education of strikers, by judicious

control of capitalists, by wise general policy to end or diminish the

evil? The railroad strikers, as a rule, are good men, sober, intelligent, and industrious." Hayes confronted two issues regarding the currency. The first was the coinage of silver, and its relation to gold. In 1873, the Coinage Act of 1873 stopped

the coinage of silver for all coins worth a dollar or more, effectively

tying the dollar to the value of gold. As a result, the money supply contracted and

the effects of the Panic of 1873 grew worse, making it more expensive

for debtors to pay debts they had contracted when currency was less

valuable. Farmers

and laborers, especially, clamored for the return of coinage in both

metals, believing the increased money supply would restore wages and

property values. Democratic Representative Richard P. Bland of Missouri proposed

a bill that would require the United States to coin as much silver as

miners could sell the government, thus increasing the money supply and

aiding debtors. William B. Allison, a Republican from Iowa offered an amendment in the Senate limiting the coinage to two to four million dollars per month, and the resulting Bland – Allison Act passed both houses of Congress in 1878. Hayes feared that the Act would cause inflation that

would be ruinous to business, effectively impairing contracts that were

based on the gold dollar, as the silver dollar proposed in the bill

would have an intrinsic value of 90 to 92 percent of the existing gold

dollar. Further,

Hayes believed that inflating the currency was an act of dishonesty,

saying "[e]xpediency and justice both demand an honest currency." He vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode his veto, the only time it did so during his presidency. The second issue concerned United States Notes (commonly called greenbacks), a form of fiat currency first

issued during the Civil War. The government accepted these notes as

valid for payment of taxes and tariffs, but unlike ordinary dollars,

they were not redeemable in gold. The Specie Payment Resumption Act of

1875 required the treasury to redeem any outstanding greenbacks in

gold, thus retiring them from circulation and restoring a single,

gold-backed currency. Sherman

agreed with Hayes's favorable opinion of the Act, and stockpiled gold

in preparation for the exchange of greenbacks for gold. Once

the public was confident that they could redeem greenbacks for specie

(gold), however, few did so; when the Act took effect in 1879, only

$130,000 out of the $346,000,000 outstanding dollars in greenbacks were

actually redeemed. Together with the Bland – Allison Act, the successful specie resumption effected a workable compromise between inflationists and hard money men

and, as the world economy began to improve, agitation for more

greenbacks and silver coinage quieted down for the rest of Hayes's term

in office. Most of Hayes's foreign policy concerns involved Latin America. In 1878, following the War of the Triple Alliance, he arbitrated a territorial dispute between Argentina and Paraguay. Hayes awarded the disputed land in the Gran Chaco region to Paraguay, and the Paraguayans honored him by renaming a city (Villa Hayes) and a department (Presidente Hayes) in his honor. Hayes was also perturbed over the plans of Ferdinand de Lesseps, the builder of the Suez Canal, to construct a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, which was then owned by Colombia. Concerned about a repetition of French adventurism in Mexico, Hayes interpreted the Monroe Doctrine firmly. In

a message to Congress, Hayes explained his opinion on the canal: "The

policy of this country is a canal under American control ... The

United States cannot consent to the surrender of this control to any

European power or any combination of European powers." The Mexican border also drew Hayes's attention. Throughout the 1870s, "lawless bands" often crossed the border on raids into Texas. Three months after taking office, Hayes granted the Army the power to pursue bandits, even if it required crossing into Mexican territory. Porfirio Díaz, the Mexican president, protested the order and sent troops to the border. The

situation calmed as Díaz and Hayes agreed to jointly pursue

bandits and Hayes agreed not to allow Mexican revolutionaries to raise

armies in the United States. The violence along the border decreased, and in 1880 Hayes revoked the order allowing pursuit into Mexico. Outside of the Western hemisphere, Hayes's biggest foreign policy concern dealt with China. In 1868, the Senate had ratified the Burlingame Treaty with China, allowing an unrestricted flow of Chinese immigrants into the country. As the economy soured after the Panic of 1873, Chinese immigrants were blamed for depressing workmen's wages. During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, anti - Chinese riots broke out in San Francisco, and a third party, the Workingman's Party, was formed with an emphasis on stopping Chinese immigration. In response, Congress passed a Chinese Exclusion Act in 1879, abrogating the 1868 treaty. Hayes vetoed the bill, believing that the United States should not abrogate treaties without negotiation. The veto drew praise among eastern liberals, but Hayes was bitterly denounced in the West. In the subsequent furor, Democrats in the House of Representatives attempted to impeach him, but narrowly failed when Republicans prevented a quorum by refusing to vote. After the veto, Assistant Secretary of State Frederick W. Seward suggested that both countries work together to reduce immigration, and he and James Burrill Angell negotiated with the Chinese to do so. Congress passed a new law to that effect, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, after Hayes left office.

Hayes and his wife, Lucy, were known for their policy of keeping an alcohol free White House, giving rise to her nickname "Lemonade Lucy." The first reception at the Hayes White House included wine. However,

Hayes was dismayed at drunken behavior at receptions hosted by

ambassadors around Washington, leading him to follow his wife's

temperance leanings. Alcohol

was not served again in the Hayes White House. Critics charged Hayes

with parsimony, but Hayes spent more money (which came out of his

personal budget) after the ban, ordering that any savings from

eliminating alcohol be used on more lavish entertainment. His temperance policy also paid political dividends, strengthening his support among Protestant ministers. Although

Secretary Evarts quipped that at the White House dinners, "water flowed

like wine," the policy was a success in convincing prohibitionists to vote Republican. Hayes appointed two Associate Justices to the Supreme Court.

The first vacancy occurred when David Davis resigned after he resigned

to enter the Senate during the election controversy of 1876. On taking

office, Hayes appointed John Marshall Harlan to the seat. A former candidate for governor of Kentucky, Harlan had been Benjamin Bristow's campaign manager at the 1876 Republican convention, and Hayes had earlier considered him for Attorney General. Hayes

submitted the nomination in October 1877, but it aroused some dissent

in the Senate because of Harlan's limited experience in public office. Harlan

was nonetheless confirmed and served on the court for thirty-four

years, in which he voted (usually in the minority) for an aggressive

enforcement of the civil rights laws. In 1880, a second seat became vacant on the resignation of Justice William Strong. Hayes nominated William Burnham Woods, a carpet bagger Republican circuit court judge from Alabama. Woods

served six years on the Court, ultimately proving a disappointment to

Hayes as he interpreted the Constitution in a manner more similar to

that of Southern Democrats than to Hayes's own preferences. Hayes attempted, unsuccessfully, to fill a third vacancy in 1881. Justice Noah Haynes Swayne resigned with the expectation that Hayes would fill his seat by appointing Stanley Matthews, who was a friend of both men. Many

Senators objected to the appointment, believing that Mathews was too

close to corporate and railroad interests, especially those of Jay Gould. The Senate adjourned without voting on the nomination. The following year, when James A. Garfield entered

the White House, he re-submitted Mathews's nomination. This time, the

Senate did vote, confirming Mathews by one vote, 24 to 23. Mathews served for eight years until his death in 1889. His opinion in Yick Wo v. Hopkins in 1886 advanced his and Hayes's views on the protection of minority rights. Hayes decided not to seek re-election in 1880,

keeping his pledge that he would not run for a second term. He was

gratified with the election of James A. Garfield to succeed him, and

consulted with him on appointments for the next administration. After Garfield's inauguration, Hayes and his family returned to Spiegel Grove. Although he remained a loyal Republican, Hayes was not too disappointed in Grover Cleveland's election to the Presidency in 1884, approving of the New York Democrat's views on civil service reform. He was also pleased at the progress of the political career of William McKinley, his army comrade and political protégé. Hayes became an active advocate for educational charities, advocating federal education subsidies for all children. He believed that education was the best way to heal the rifts in American society and allow individuals to improve themselves. Hayes was appointed to the Board of Trustees of The Ohio State University, the school he helped found during his time as governor of Ohio, in 1887. He emphasized the need for vocational, as well as academic, education: "I preach the gospel of work," he wrote, "I believe in skilled labor as a part of education." He urged Congress, unsuccessfully, to pass a bill written by Senator Henry W. Blair that would have allowed federal aid for education for the first time. Hayes gave a speech in 1889 encouraging black students to apply for scholarships from the Slater Fund, one of the charities with which he was affiliated. One such student, W.E.B. Du Bois, received a scholarship in 1892. Hayes also advocated better prison conditions. In

retirement, Hayes was troubled by the disparity between the rich and

the poor, saying in an 1886 speech that "free government cannot long

endure if property is largely in a few hands and large masses of people

are unable to earn homes, education, and a support in old age." The following year, Hayes recorded his thoughts on that subject in his diary: "In

church it occurred to me that it is time for the public to hear that

the giant evil and danger in this country, the danger which transcends

all others, is the vast wealth owned or controlled by a few persons.

Money is power. In Congress, in state legislatures, in city councils,

in the courts, in the political conventions, in the press, in the

pulpit, in the circles of the educated and the talented, its influence

is growing greater and greater. Excessive wealth in the hands of the

few means extreme poverty, ignorance, vice, and wretchedness as the lot

of the many. It is not yet time to debate about the remedy. The

previous question is as to the danger — the evil. Let the people be fully

informed and convinced as to the evil. Let them earnestly seek the

remedy and it will be found. Fully to know the evil is the first step

towards reaching its eradication. Henry George is

strong when he portrays the rottenness of the present system. We are,

to say the least, not yet ready for his remedy. We may reach and remove

the difficulty by changes in the laws regulating corporations, descents

of property, wills, trusts, taxation, and a host of other important

interests, not omitting lands and other property." Hayes was greatly saddened by his wife's death in 1889. He wrote that "the soul had left [Spiegel Grove]" when she died. After Lucy's death, Hayes's daughter, Fanny, became his traveling companion and he enjoyed visits from his grandchildren. In 1890, he chaired the Lake Mohonk Conference on the Negro Question, a gathering of reformers that discussed racial issues. Hayes died of complications of a heart attack at his home on January 17, 1893. His last words were "I know that I'm going where Lucy is." President-elect

Grover Cleveland and Ohio Governor William McKinley led the funeral

procession that followed Hayes's body until he was interred in Oakwood Cemetery. Following the donation of his home to the state of Ohio for the Spiegel Grove State Park, he was re-interred there in 1915. The following year the Hayes Commemorative Library and Museum,

the first presidential library in the United States, was opened on the

site, funded by contributions from the state of Ohio and Hayes's family.