<Back to Index>

- Economist Victor de Riqueti, Marquis de Mirabeau, 1715

- Novelist Teresa de la Parra, 1889

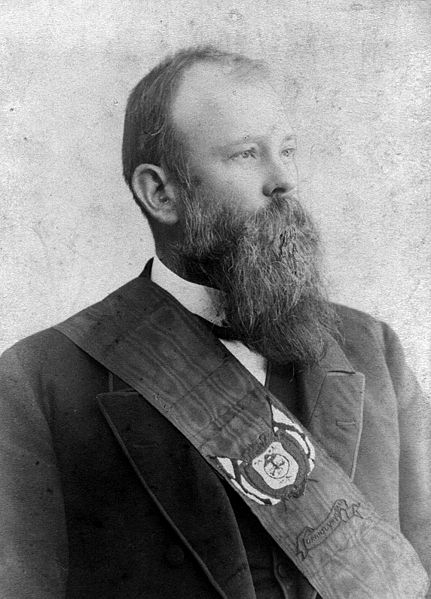

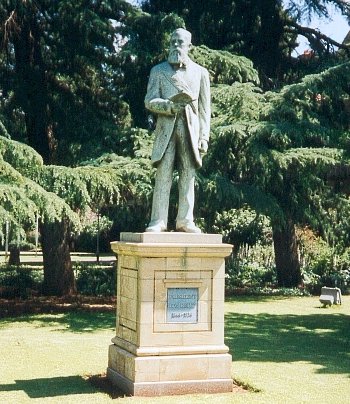

- 5th State President of the Orange Free State Francis William Reitz, Jr., 1844

PAGE SPONSOR

Francis William Reitz, Jr. (Swellendam, 5 October 1844 – Cape Town, 27 March 1934) was a South African lawyer, politician, statesman, publicist and poet, member of parliament of the Cape Colony, Chief Justice and fifth State President of the Orange Free State, State Secretary of the South African Republic at the time of the Second Boer War, and the first president of the Senate of the Union of South Africa.

Reitz

had an extremely varied political and judicial career that lasted for

over forty-five years and spanned four separate political entities: the Cape Colony, the Orange Free State, the South African Republic, and the Union of South Africa.

Trained as a lawyer in Cape Town and London, Reitz started off in law

practice and diamond prospecting before being appointed Chief Justice

of the Orange Free State. In

the Orange Free State Reitz played an important role in the

modernisation of the legal system and the state's administrative

organisation. At the same time he was also prominent in public life,

getting involved in the Afrikaner language and culture movement, and

cultural life in general. Reitz was a popular personality, both for his politics and his openness. When State President Brand suddenly

died in 1888, Reitz won the presidential elections unopposed. After

being re-elected in 1895, subsequently making a trip to Europe, Reitz

fell seriously ill, and had to retire. In

1898, now recovered, he was appointed State Secretary of the South

African Republic, and became a leading Afrikaner political figure

during the Second Boer War. Reluctant to shift allegiance to the British, Reitz went into voluntary exile after the war ended. Several years later he returned to South Africa and set up a law practice again, in Pretoria. In the late 1900s he became involved in politics once more, and upon the declaration of the Union of South Africa in 1910, Reitz was chosen the first president of the Senate. Reitz

was an important figure in Afrikaner cultural life during most of his

life, especially through his poems and other publications. Francis William Reitz, Jr., was born was born in Swellendam on 5 October 1844, as the son of Francis William Reitz, Sr., model farmer, agriculturalist and

politician, and Cornelia Magdalena Deneys. He was the seventh child in

a family of twelve. He grew up at Rhenosterfontein, the model farm (Afrikaans: plaas) of his father, situated on the borders of the Breederivier (Broad River) in the Cape Colony. Reitz married twice. His first marriage (Cape Town 24 June 1874) was to Blanka Thesen (Stavanger, Norway, 15 October 1854 – Bloemfontein, 5 October 1887). She was the sister of Charles Wilhelm Thesen, and the daughter of Arnt Leonard Thesen, tradesman, and Anne Cathrine Margarethe Brandt. The Thesen family had settled in Knysna, Cape Colony,

from Norway in 1869. The couple had seven sons and one daughter. After

the death of his first wife Reitz remarried (Bloemfontein, 11 December

1889) with Cornelia Maria Theresia Mulder (Delft, Netherlands, 25 December 1863 – Cape Town 2 January 1935), daughter of Johannes Adrianus Mulder, typesetter, and Engelina Johanna van Hamme. At the time of her marriage Mulder was acting director of the Eunice Ladies' Institute at Bloemfontein. With his second wife he had six sons and one daughter. Deneys, his son, fought against the British in the Second Boer War, commanded the First Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers during World War I and served as a Member of the Union Parliament, Cabinet Minister, Deputy Prime Minister (1939 – 1943), and South African High Commissioner (1944) to the Court of St. James's. His book, Commando: A Boer Journal Of The Boer War, has for many years been regarded as one of the best narratives of war and adventure in the English language. Reitz

received his earliest schooling at home, from a governess, and at a

neighbouring farm. When he was nine years old, he went to the Rouwkoop

Boarding School in Rondebosch (Cape Town). Here he stood out for his academic achievements and was subsequently elected Queen's Scholar by the Senate of the South African College in

Cape Town. In the six years he spent at the College, after arriving in

1857, he received a broad education in arts and sciences, and developed

himself into a well balanced young man with obvious leadership

qualities. He graduated from South African College in September 1863

with the equivalent of a modern bachelor's degree in arts and sciences. By

then, Reitz had developed a keen interest in law, and he continued his

studies at South African College, reading law with professor F.S.

Watermeyer. The latter's death only months after Reitz started working

with him, made Reitz decide to continue his studies in London, at the Inner Temple.

It was a decision that needed deliberation, as his father was hoping

for his son to return to the farm in due time, and the financial

situation of the family was not strong. However, Reitz did go to

London, and finished his studies successfully. He was called to the bar at Westminster on 11 June 1867. During his time in England Reitz became interested in politics, and regularly attended sessions of the House of Commons. Before returning to South Africa he made a tour of Europe. Back in South Africa, Reitz established himself as a barrister in Cape Town, where he was called to the bar on 23 January 1868. In the beginning Reitz found it hard to make a living, as competition among lawyers in Cape Town was

quite severe at this time. Nevertheless he succeeded in making a name

for himself, due to his sharp legal mind and his social intelligence.

Being part of the western Circuit Court of

the Cape Colony gave him a lot of experience in a very short time. At

the same time, Reitz nurtured his political interests by writing lead

articles for the Cape Argus newspaper,

for which he also reported on the proceedings of the Cape Parliament

and acted as deputy editor. In 1870 Reitz moved his legal practice to Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State. The discovery of diamonds on the banks of the Vaal River,

Reitz thought, would lead to a growth of legal work and enable him to

set up a thriving practice. This was not to be, however, and after a

few months Reitz left Bloemfontein to set up as a diamond prospector in Griqualand West, where he bought a small claim near Pniel from the Berlin Missionary Society.

This enterprise also proved unsuccessful, and again after only a few

months Reitz returned to Cape Town. This time, his Cape Town law

practice was successful, ironically because of the British annexation

of the Orange Free State diamondfields (1871) and the economic

prosperity this emanated for the Cape Colony. In 1873 Reitz was asked to represent the district of Beaufort West in

the Cape Parliament. The day he took his seat, 30 May, his father, who

was the representative for Swellendam, announced his retirement from

the Assembly. As so many of Reitz's activities up to that point, his

parliamentary career was short lived. Only two months later, President Johannes Brand of the Orange Free State offered Reitz the position of chairman of the newly formed Appellate Court of the Orange Free State, despite the fact that Reitz was not fully qualified (inter alia too

young). Reitz refused the offer for this reason, but when another

candidate also refused, Brand insisted on the nomination of Reitz, and

convinced the Volksraad to appoint him. With his appointment to the judiciary of

the Orange Free State, Reitz came into his own. His arrival – now

almost thirty years old and just married – in Bloemfontein in August

1874 was the start of a residency of twenty-one years, as well as the

start of a glowing career, to be crowned with his election as State President. Before

the mid 1870s, the judicial system of the Orange Free State was rather

amateurish and haphazard in character, particularly because most of the

judges were legally unqualified. Most of the judicial procedures were

in the hands of district magistrates, the so-called Landdrosts,

whose main task was administrative. Reitz's first task was to

ameliorate this situation, which he did with much vigour. Well within

his first year of tenure the Volksraad passed an Ordinance, in which

both a professional Circuit Court and a Supreme Court were called into being. Reitz became the first president of the Supreme Court and

consequently also the first Chief Justice of the Orange Free State.

Right from the beginning Reitz showed himself to be a fighter, opposing

the Volksraad on more than one occasion, tackling deeply ingrained

political traditions that stood in the way of the modernisation of the

judicial system, but also fighting hard to get the salaries and

pensions of state officials improved. As a colonial –

he was born in the Cape Colony after all – he had to win the confidence

of the Boer population to have his ideas accepted. This he did by

traveling with the Circuit Court through the country for over ten years, acquiring insight into and empathy for

their way of life and their often conservative and always God fearing

beliefs. It helped that Reitz himself was a religious person and that

he had started out in life in the Afrikaans speaking countryside of the

Cape Colony. Eventually he became the symbol of Afrikanerdom for many Orange Free Staters. Institutionally,

Reitz did much for the codification and review of the laws of the

Orange Free State. With his colleagues C.J. Vels, O.J. Truter, and J.G. Fraser Reitz published the first Ordonnantie boek van den Oranje Vrijstaat (Ordinance

Book of the Orange Free State) in 1877, making the acts and ordinances

of the republic available to the larger public. He also played a role

in the revision of the constitution of the Orange Free State, with

regard to articles on citizenship and the right to vote, was chairman

of the examination committee for aspirant practitioners, and

contributed to the improvement of the prison system and the district

administration. Already

in 1878, voices sounded for Reitz to run for the presidency, but

President Brand's position was still very strong and Reitz openly

praised his qualities and refused to stand against him. In the late

1870s and early 1880s the political temperature ran high in the Orange

Free State. The annexation of the South African Republic (Transvaal) by the British in 1877 and the First Anglo - Boer War of

1880 - 1881 in which that republic regained its autonomy impacted deeply

on political sentiments in the Orange Free State. On the one hand there

were those who propagated caution in the relationship with the British,

on the other there developed a political movement that strongly

propagated a (reawakened) Afrikaner national consciousness. Reitz was part of the latter, and together with C.L.F. Borckenhagen, editor of the Bloemfontein Express newspaper, he wrote a constitution for the Afrikaner Bond (Afrikaner Union), a political party originally set up by leading Afrikaner politicians in the Cape Colony, like Rev S.J. du Toit and his Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners ('Society of True Afrikaners') and Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr and the Zuidafrikaansche Boeren Beschermings Vereeniging ('South

African Boer Protection Association'). Among the supporters of this new

Afrikaner nationalism in the Orange Free State was also Reitz's

successor, M.T. Steyn,

then still a young lawyer. The constitution was presented in April

1881, and several months later Reitz became the chairman of the Bond. His

overt political activities earned Reitz criticism from those who feared

a breakdown of relations with the British. It is obvious, however, that

a wind of change was blowing through the Boer republics and among the Afrikaners in the Cape Colony, which was to change Anglo - Boer relations drastically. In

the Orange Free State President Brand was one of the politicians who

held on to a more cautious and consolidating policy towards the British

government at the Cape, maintaining strict neutrality. In this position

Brand followed the habit of a lifetime, and it earned him a British knighthood.

Despite the changing political climate and the polarisation of

political positions, Brand remained hugely popular with the burghers of

the Orange Free State. The presidential elections of 1883 could on

content have become a political battle between the pan-Dutch Afrikaner Bond supporters

and followers of the Brand line. However, Reitz, as the ideal pan-Dutch

candidate, again refused to stand against Brand. Only when Brand died

in office five years later, the time was ripe for change. Reitz stood

candidate and won a landslide victory on the ticket of Afrikaner nationalism. He was inaugurated as state president in the Tweetoringkerk (Two-Towers Church) in Bloemfontein on 10 January 1889. As president Reitz was one of the first Afrikaners to actively develop a so-called Bantu policy,

in philosophy and terminology going beyond contemporary ideas on

segregation between white and black. Under his government Indian

immigrants were by law forbidden to settle in the Orange Free State

(1890). This led to a confrontation with the British government and an

extensive correspondence between Reitz and the British high commissioner in Cape Town, in which internal sovereignty was claimed and established. In

economic terms, the late 1880s were a period of growth in the Orange

Free State. Agriculture picked up, and the railway system became an

important source of income as well. Reitz was instrumental in the

modernisation of farming, propagating new techniques and a scientific

approach to the prevention of plagues. Here Reitz showed himself the

agriculturalist and model farmer his father had been before him. Under Reitz's presidency the new meeting hall for the Volksraad, the so-called Vierde Raadszaal (Fourth

Council Hall) was opened (1893), and the new Government Building

received a second floor (1895). Outside Bloemfontein the road network

received attention. As could be expected, immediately after he was inaugurated, Reitz contacted the government of the South African Republic with

the objective to establish new and closer political ties. Already on 4

March 1889 the Orange Free State and the South African Republic

concluded a treaty of common defence at Potchefstroom.

Treaties about trade and the railways were to follow. Even earlier, in

January 1889, the Volksraad charged Reitz to negotiate a customs treaty

with both the British South African colonies and the South African Republic. On 20 March 1889 a Customs Conference was held in

Bloemfontein which led to an agreement between the Orange Free State

and the Cape Colony which was hugely beneficial for the former. The

economic benefits grew further when new railway lines were opened

between the Cape Colony and Bloemfontein (1890) and between

Bloemfontein and Johannesburg (1892),

directly connecting Cape Town with Johannesburg and turning the Orange

Free State into a transit economy. For Reitz the development of a

unified South African railway system was also a political goal: the

railways as a means to diminish mutual distrust and create unity and

mutual understanding between the white population of South Africa. Reitz's policies were appreciated by the Volksraad,

reflecting the change in the mood of the Afrikaner electorate towards

Afrikaner nationalism. Months before the presidential election of 1893

the Volksraad endorsed Reitz's candidature with a vote of forty-three

against eighteen. Reitz accepted the endorsement on the condition that

he be allowed three months leave to Europe. On 22 November 1893 he was

re-elected, again with a landslide majority. The trip to Europe was far from just a family holiday. In Britain Reitz

made some strong public statements, defending the republican system of

government in South Africa and opposing British intervention in 'Bantu

affairs'. On the continent Reitz was received by several heads of state

and political leaders. In October 1894 he returned in Bloemfontein.

Soon after Reitz was diagnosed with hepatitis, which moreover affected his already strained nerves and led to sleeplessness.

The situation was so serious that he eventually had to resign the

presidency. The Volksraad accepted his resignation on 11 December 1895. In

June 1896 Reitz travelled to Europe once more on a five-month trip to

recover from his debilitating illness. On his return to South Africa he

established himself in Pretoria in the South African Republic in July 1897, where he set up a new law practice. Reitz did not stay a private person for long. A conflict between the South African Republic legislature and judiciary resulted in the dismissal of the Chief Justice. Reitz then took up an appointment as judge in early 1898 and quickly became part of the inner circle of the Transvaal administration.

At the time the relationship with the British was already rapidly

deteriorating and the government of the South African Republic was

taking action to reinforce its national and international position. One

of the measures taken was to replace State Secretary W.J. Leyds, who had the Dutch nationality, with a South African. Leyds was appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary in Europe to represent the Republic abroad. Reitz took his place as State Secretary in June 1898, after Abraham Fischer had declined. As

State Secretary Reitz had a complicated and hefty job. After the State

President he was the most important member of the Executive Council (Uitvoerende Raad).

As the most senior civil servant he was responsible for the oversight

over the implementation of the laws and regulations, as well as for all

the correspondence of the President, official government reports, etc.

He was also an intermediary between the Executive Council and

parliament, the First and Second Volksraad, and a key figure in the

foreign affairs of the State. Experienced and well organised as he

himself was Reitz managed to quickly modernise the structure of the

state apparatus, by implementing regulations for the running of the

government departments, appointing an archivist for his own, and by

prescribing that all correspondence with the government should be in Dutch. The State President of the South African Republic, Paul Kruger,

was not an easy man to work with, and in some circles it was predicted

that Reitz would quickly find himself subordinated to Kruger. This was

not the case, however. On occasion the two men clashed on matters of

policy, but Reitz remained true to his own convictions, gaining some

influence over Kruger in the process. Originally praised by the British

for his diplomatic courtesy, their attitude quickly changed when they

understood that Reitz was a protagonist of Transvaal independence.

Reitz was sometimes rather brazen in his political statements, so when

he – incorrectly – claimed the South African Republic to be a fully

sovereign state, the British jumped on him. In view of rapidly mounting British pressure and an ensuing armed conflict over the position of the Uitlanders and economic control over the Witwatersrand gold

fields, foreign policy in the South African Republic was eventually

determined by a triumvirate: State President Kruger, State Secretary

Reitz, and State Attorney General J.C. Smuts.

During 1899 they decided that an offensive attitude towards British

demands was the only way forward, despite the risks this entailed.

Reitz sought and received the support of the Orange Free State for this

approach. On 9 October 1899 the South African Republic and the Orange

Free State issued a joint ultimatum to the British government to

retract their demands. The British government did not give in to the ultimatum, and two days later, on 11 October 1899, the Second Anglo - Boer War (South African War) broke out. When the British army marched on Pretoria in

May 1900, the government was forced to flee the capital. From that

moment on, Reitz was responsible for the continuous relocation of its

seat throughout the Transvaal, which occurred sixty-two times until

March 1902. In May of that year, Reitz took an active part in the peace

negotiations with the British, and he was one of the signatories of the Treaty of Vereeniging, signed in Pretoria on 31 May 1902. Although instrumental in drafting the Treaty of Vereeniging,

Reitz personally did not want to swear allegiance to the British

government, and he chose to go into exile. On 4 July 1902 he left South

Africa and joined his wife and children in the Netherlands. To alleviate his financial troubles, Reitz set out on a lecture tour in the United States. Due

to a waning interest in the Boer cause now that the war was over, the

tour failed, forcing Reitz to return to the Netherlands. Here his

health failed him again, leading to hospitalisation and an extensive

period of convalescing. During this time he was supported by his friends W.J. Leyds and H.P.N. Muller and the Nederlandsch Zuid-Afrikaansche Vereeniging (Dutch South-African Society). In 1907, after the old Boer republics received self-government, and in the run-up to the formation of the Union of South Africa, leading Afrikaner politicians J.C. Smuts and L. Botha asked Reitz to return to South Africa and play a role in politics again. Together with his wife, he established himself in Sea Point, Cape Town. In 1910, already seventy-six years old, he was appointed president of the Senate of the newly formed Union of South Africa. These

were no easy years, again, as former Afrikaner compatriots found each

other on two sides of the political fence, in a rapidly changing world.

As in his earlier life, Reitz remained a man of outspoken convictions,

which he aired freely. As such, he came into conflict with the Smuts

government, and in 1920 he was not re-appointed as president of the

Senate. He did remain a member of that House until 1929, however. As an important public figure, Reitz was honoured and remembered in different ways. In 1923 Reitz the University of Stellenbosch bestowed on him an honorary doctorate in law for his public services. Already in 1889, a village was named after him in the Orange Free State. In 1894 one also named a village after his second wife, Cornelia. A ship named after him, the President Reitz, sank off Port Elizabeth in 1947. The Jubilee Diamond, found in the Free State village of Jagersfontein in 1895 was originally named the Reitz Diamond, but renamed in honour of the sixtieth anniversary of the coronation of Queen Victoria in 1897. When he finally retired from public life, Reitz moved to Gordon's Bay, but returned to Cape Town several years later, where he had a house in Tamboerskloof and was taken care of by his daughter Bessie, a medical doctor. He remained active to the end with writing and translating. Reitz died at his house Botuin on 27 March 1934, and received a state funeral three days later, with a funeral service at the Grote Kerk. He was buried at the Woltemade cemetery at Maitland. Reitz

was an important figure in Afrikaner cultural life. He was a poet, and

published many poems in Afrikaans, making him a progenitor of the

development of Afrikaans as a cultural language. As such he sympathised with the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners (Society of Real Afrikaners),

established in the Cape Colony in 1875. Although he never became a

member himself, he was an active contributor to the society's journal, Die Suid-Afrikaansche Patriot. With

his literary work, Reitz was solidly anchored in the so-called First

Afrikaans Language Movement, although he was less interested in the

didactic drive of that movement than in writing in Afrikaans as a

purely cultural activity. Much of his work was based on English texts,

which he translated, edited, and adapted. In the process he produced

completely new works of art. For

Reitz, Afrikaans was predominantly a language of culture, not of

government, where he propagated the use of the official language of the

Boer republics, Dutch.

During his presidency of the Orange Free State, where the use of

English was significant among the burghers, he strongly promoted the

use of Dutch, against politicians like John G. Fraser and others who were in favour of English. Institutionally, Reitz promoted the foundation of the Letterkundige en Wetenschappelijke Vereeniging (Literary

and Scientific Society) of the Orange Free State, of which he was

chairman for a while, the library at Bloemfontein, and the National

Museum of the Orange Free State. At

the advent of the South African War (Second Anglo - Boer War), F.W.

Reitz, in his capacity of State Secretary of the South African Republic, published an overview of Anglo - Boer relations in the

nineteenth century in Dutch, under the title Eene eeuw van onrecht. The book was an important propaganda document in the war. The

actual authorship of the book is unclear. The second Dutch edition of

the book carried the text 'Op last van den staatssekretaris der Z.A.R.,

F.W. Reitz' ('By order of the State Secretary of the S.A.R., F.W.

Reitz'). J.C. Smuts is

indicated as author, but probably only edited the introduction and the

end of the book, in co-operation with E.J.P. Jorissen. The rest of the

text was probably prepared by J. de Villiers Roos. In

1900, translations appeared in German and English. The English

translation only carried the name of Reitz, and has a preface by W.T. Stead. The English edition contained more material than the original Dutch edition.