<Back to Index>

- Geologist John William Dawson, 1820

- Composer Anselm Hüttenbrenner, 1794

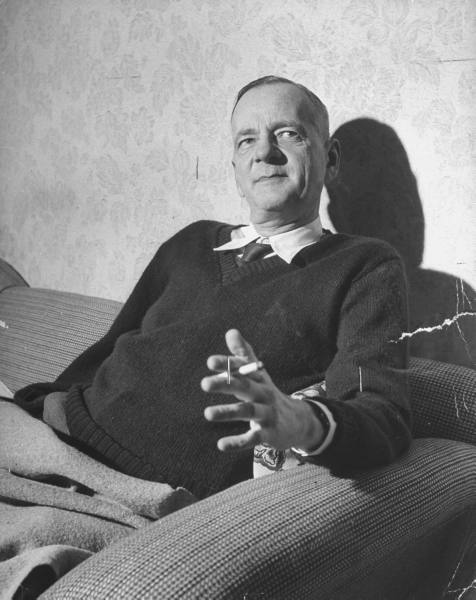

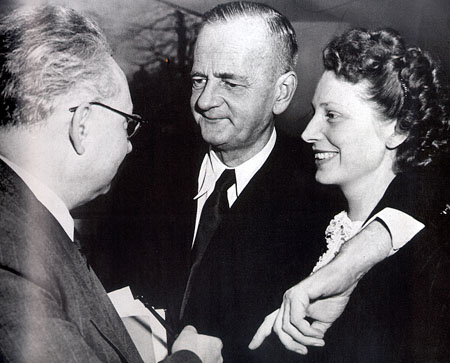

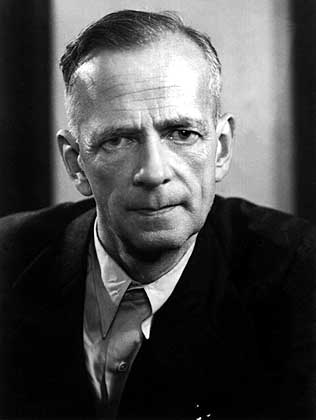

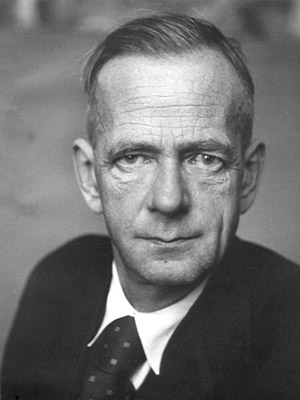

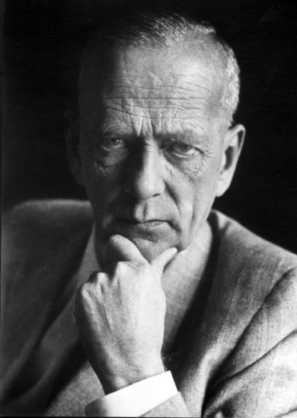

- Leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany Kurt Schumacher, 1895

PAGE SPONSOR

Dr. Kurt Schumacher (13 October 1895 - 20 August 1952), was the leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany from 1945 to 1952.

Kurt Schumacher was born in Kulm in West Prussia (now Chełmno in Poland), the son of a small businessman. He was a brilliant student, but when the First World War broke out in 1914 he immediately abandoned his studies and joined the German Army. In December, west of Łowicz in Poland, he was so badly wounded that his right arm had to be amputated. He returned to his studies in Berlin, graduating in law and politics, and became a dedicated socialist.

In 1918 Schumacher joined the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and led ex-servicemen in forming Workers and Soldiers Councils in Berlin during the revolutionary days following the fall of the German monarchy. He opposed various attempts by Communist groups to seize power. In 1920 the SPD sent him to Stuttgart to edit the party newspaper there, the Schwäbische Tagwacht.

Schumacher was elected to the Württemberg Landtag (state legislature) in 1924 and in 1928 became the SPD leader in the state. When the Nazi Party rose

to prominence, Schumacher helped organize socialist militias to oppose

them. In 1930 he was elected to the national legislature, the Reichstag. In August 1932 he was elected to the SPD leadership group; at age 38 he was the youngest SPD member of the legislature. The inability of the SPD and the German Communist Party to

form a united front meant that they could not prevent the Nazis coming

to power in January 1933. Schumacher was arrested in July and was

severely beaten in prison. He spent the next ten years in concentration camps at Heuberg, Kuhberg, Flossenbürg and Dachau.

The camp at Dachau was intended for people whom the Nazis wanted to

keep alive, and the fact that he was a disabled ex-service man gained

Schumacher some leniency, but he risked his life through repeated

defiance and hunger strikes. In

1943, when Schumacher was near death, his brother-in-law succeeded in

persuading a Nazi official to have him released into his custody. He

was arrested again in late 1944, and he was in Neuengamme concentration camp when the British arrived in April 1945. Schumacher wanted to lead the SPD and bring Germany to socialism. By May he was already reorganising the SPD in Hanover, without the permission of the occupation authorities. He soon found himself in a battle with Otto Grotewohl,

the leader of the SPD in the Soviet Zone of Occupation, who was arguing

that the SPD should merge with the Communists to form a united

socialist party. Schumacher rejected Grotewohl's plan. In August he

called an SPD convention in Hanover, which elected him as "western

leader" of the party. In

January 1946 the British and Americans allowed the SPD to reform itself

as a national party, with Schumacher as leader. As the only SPD leader

who had spent the whole Nazi period in Germany, without collaborating,

he had enormous prestige. He was certain that his right to lead Germany

would be recognised both by the Allies and by the German electorate. But Schumacher met his match in Konrad Adenauer, the former mayor of Cologne, whom the Americans, not

wanting to see socialism of any kind in Germany, were grooming for

leadership. Adenauer united most of the prewar German conservatives into a new party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). Schumacher campaigned through 1948 and 1949 for a united socialist Germany, and particularly for the nationalisation of heavy industry, whose owners he blamed for funding the Nazis' rise to power. When the occupying powers opposed

his ideas, he denounced them. Adenauer opposed socialism on principle,

and also argued that the quickest way to get the Allies to restore

self-government to Germany was to co-operate with them. Schumacher

wanted a new constitution with a strong national presidency, confident

that he would occupy that post. But the first draft of the 1949 Grundgesetz provided

for a federal system with a weak national government, as favoured both

by the Allies and the CDU. Schumacher refused to give way on this, and

eventually the Allies, keen to get the new German state functioning in

the face of the Soviet challenge, conceded some of what Schumacher

wanted. The new federal government would be dominant over the states,

although the president would be weak. The

Federal Republic's first national elections were held in August 1949.

Schumacher was convinced he would win, and most observers agreed with

him. But Adenauder's new CDU had several advantages over the SPD. Some

of the SPD's strongest areas in pre-war Germany were now in the Soviet

Zone, while the most conservative parts of the country - Bavaria and the Rhineland -

were in the new Federal Republic of Germany. In addition both the

American and French occupying powers favoured Adenauer and did all they

could to assist his campaign; the British remained neutral. Further, the onset of the Cold War,

and particularly the behavior of the Soviets and the German Communists

in the Soviet Zone, produced an anti-socialist reaction in Germany as

elsewhere. The SPD would probably have won an election in 1945; by 1949

the tide had turned. The German economy was also reviving, thanks

mainly to the currency reform of the CDU's Ludwig Erhard.

Matters were complicated by Schumacher's ill-health: in September 1948

he had one of his legs amputated. Germans admired Schumacher's courage,

but they doubted that he could carry out the duties of federal

Chancellor. Although Schumacher's SPD won the most seats in the election, the CDU was able to form a coalition government with the Free Democratic Party, the Christian Social Union, and the German Party,

and Adenauer was voted Chancellor. This was a shock to Schumacher. He

refused to co-operate in parliamentary matters and denounced the CDU as

agents of the capitalists and foreign powers. Although he also

denounced the Communists, and in fact organised an underground SPD

resistance network in eastern Germany, his anti-capitalist and

anti-Western rhetoric sounded sufficiently similar to Communist propaganda to undermine his support. Schumacher further damaged his standing by opposing the emerging new organisations of European co-operation, the Council of Europe, the European Coal and Steel Community and the European Defence Community,

which he saw as devices for strengthening capitalism (which in a way

they were), and for extending Allied control over Germany (which they

were not). This

stand aroused the opposition of the other west European socialist

parties, and eventually the SPD overruled him and sent delegates to the

Council of Europe. During

the rest of Adenauer's first term of office, Schumacher continued to

oppose his government, but the rapid rise in German prosperity, the

intensification of the Cold War and Adenauer's increasing success in

getting Germany accepted in the international community all worked to

undermine Schumacher's position. The SPD began to have serious doubts

about going into another election with Schumacher as leader,

particularly when he had a stroke in December 1951. They were spared

having to deal with this dilemma when Schumacher died suddenly in

August 1952. Adenauer admired Schumacher's integrity, will power and courage, even while opposing his policies, and was shocked at his death. "Despite

our differences", he said, "we were united in a common goal, to do

everything possible for the benefit and well being of our people."