<Back to Index>

- Philologist Justus Lipsius (Joose Lips), 1547

- Painter Luca Giordano, 1634

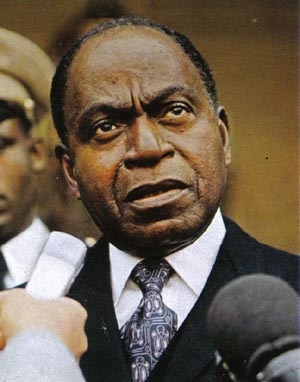

- 1st President of Côte d'Ivoire Félix Houphouët Boigny, 1905

PAGE SPONSOR

Félix Houphouët-Boigny (18 October 1905 – 7 December 1993), affectionately called Papa Houphouët or Le Vieux, was the first President of Côte d'Ivoire. Originally a village chief, he worked as a doctor, an administrator of a plantation, and a union leader, before being elected to the French Parliament and serving in a number of ministerial positions in the French government. From the 1940s until his death, he played a leading role in the decolonization of Africa and in his country's politics.

Under Houphouët-Boigny's politically moderate leadership,

Côte d'Ivoire prospered economically. This success, uncommon in

poverty ridden West Africa, became known as the "Ivorian miracle" and

was due to a combination of sound planning, the maintenance of strong

ties with the West (particularly France), and development of the

country's significant coffee and cocoa industries. However, the

exploitation of the agricultural sector caused difficulties in 1980,

after a sharp drop in the prices of coffee and cocoa. Throughout his

presidency, Houphouët-Boigny maintained a close relationship with

France, a policy known as Françafrique, and he built a close friendship with Jacques Foccart, the chief adviser on African policy in the de Gaulle and Pompidou governments. He aided the conspirators who ousted Kwame Nkrumah from power in 1966, took part in the coup against Mathieu Kérékou in 1977, and was suspected of involvement in the 1987 coup that removed Thomas Sankara from power in Burkina Faso. Houphouët - Boigny maintained an ardently anticommunist foreign policy, which resulted in, among other things, severing diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1969 (after first establishing relations in 1967) and restablishing them in February 1986, refusing to recognise the People's Republic of China until 1983, and providing assistance to UNITA, a United States supported, anti-communist rebel movement in Angola. In

the West, Houphouët - Boigny was commonly known as the "Sage of

Africa" or the "Grand Old Man of Africa". Houphouët - Boigny moved

the country's capital from Abidjan to his hometown of Yamoussoukro and built the world's largest church there, the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro, at a cost of US$300

million. At the time of his death, he was the longest serving leader in

Africa's history and the third longest serving leader in the world,

after Fidel Castro of Cuba and Kim Il-sung of North Korea. In 1989, UNESCO created the Félix Houphouët - Boigny Peace Prize for

the "safeguarding, maintaining and seeking of peace". After his death,

conditions in Côte d'Ivoire quickly deteriorated. From 1994 until

2002, there were a number of coups d'etat, a currency devaluation, an economic recession, and, beginning in 2002, a civil war. According to his official biography, Houphouët - Boigny was probably born on 18 October 1905, in Yamoussoukro, Côte d'Ivoire, to a family of chiefs of the Baoulé people. Unofficial accounts, however, place his birth date up to seven years earlier. Born into the animist Akouès tribe, he was given the name Dia Houphouët: his first name Dia means

"prophet" or "magician" and his surname came from his father, N'Doli

Houphouët. Dia Houphouët was the great - nephew of Queen

Yamousso and the village chief, Kouassi N'Go. When N'Go was murdered in

1910, Dia was called on to succeed him as chief. Due to his young age, his stepfather Gbro Diby ruled as regent, Dia's father having already died. Houphouët - Boigny

descended from tribal chiefs through his mother, Kimou N'Drive (also

known as N’Dri Kan), who died in 1936. Doubts remain as to the identity of his father, N'Doli. Officially a native of the N’Zipri of Didiévi tribe, N’Doli Houphouët died shortly after the birth of his son Augustin, although

no reliable information regarding his death exists. This uncertainty

has given rise to rumors, including a widespread one that his father

was a Sudanese born Muslim named Cissé. Houphouët - Boigny had two elder sisters, Faitai (1898? - 1998) and Adjoua (d. 1987), as well as a younger brother Augustin (d. 1939). Recognising

his place in the hierarchy, the colonial administration sent

Houphouët to school at the military post in Bonzi, not far from

his village, despite strenuous objections from relatives, especially

his grandaunt Yamousso. In 1915, he was transferred to the école primaire supérieure (secondary school) at Bingerville in spite of his family's reluctance. The same year, at Bingerville, he converted to Christianity; he considered it a modern religion and an obstacle to the spread of Islam. He chose to be christened Félix. First in his class, he was accepted into the École William Ponty in 1919, and earned a teaching degree. In 1921, he attended the École de médecine de l'AOF (French West Africa School of Medicine) in Senegal, where he came first in his class in 1925 and qualified as a medical assistant. However, he never completed his studies in medicine and could only aspire to a career as a médecin africain, a poorly paid doctor. On 26 October 1925, Houphouët began his career as a doctor's aide at a hospital in Abidjan, where he founded an association of indigenous medical personnel. This undertaking proved short lived as the colonial administration viewed it unsympathetically, considering it a trade union. As a consequence, they decided to move Houphouët to a particularly insanitary hospital in Guiglo on 27 April 1927. After he proved his considerable talents, however, he was promoted on 17 September 1929 to a post in Abengourou, which until then had been reserved for Europeans. At Abengourou, Houphouët witnessed the mistreatment of indigenous cocoa farmers by the colonists. In 1932, he decided to act, leading a movement of farmers against the

influential white landowners and for the economic policies of the

colonial government, who favoured the farmers. On 22 December, he published an article under a pseudonym titled On nous a trop volés (They have stolen too much from us), which appeared in the Trait d'union, an Ivorian socialist newspaper. The following year, Houphouët was summoned by his tribe to assume the responsibilities of village chief, but preferring to pursue his medical career, he deferred in favour of his younger brother Augustin. However, wishing to live closer to his village, he obtained a transfer to Dimbokro on 3 February 1934 and then to Toumodi on 28 June 1936. While

Houphouët had displayed professional qualities, his attitude had

chafed those around him. As a result, in September 1938, his clinical

director demanded that he choose between his job as a doctor and his

involvement in local politics. The choice was quickly made for him: his

brother died in 1939, and Houphouët became chef de canton (an office created by the colonial administration so to collect the demanded tax quota). Due to this, he ended his medical career the next year. By becoming chef de canton, Houphouët assumed responsibility for the administration of Akouè,

a canton which comprised 36 villages. He also took charge of the family

plantation — at the time one of the most important in the country — and

worked to diversify its rubber, cocoa and coffee crops. He soon became one of Africa's richest farmers. On 3 September 1944, he established, in cooperation with the colonial administration, the African Agricultural Union (Syndicat agricole africain,

SAA). Under his presidency, the SAA brought together African farmers

who were dissatisfied with their working conditions and worked to

protect their interests against those of European planters. Anti - colonialist and anti - racist, the organisation demanded better working conditions, higher wages, and the abolition of unfree labor. The union quickly received the support of nearly 20,000 plantation workers, together with that of the left wing French administrators placed in office by the Provisional Government.

Its success irritated colonists to the extent that they took legal

action against Houphouët, accusing him of being anti-French for

never seeking French citizenship. However, Houphouët befriended

the Inspector Minister of the Colonies, who ordered the charges dropped. They were more successful in obtaining the replacement of the sympathetic Governor André Latrille with the hostile Governor Henry de Mauduit. Houphouët

entered electoral politics in August 1945, when elections for the

Abidjan city council were held for the first time. The French electoral

rules established a common roll: half of the elected would have to be

French citizens (who were mostly Europeans) and the other half

non-citizens. Houphouët reacted by creating a multi - ethnic

all - African roll with both non-citizens and citizens (mostly

Senegalese with French citizenship). As a result, most of the African

contenders

withdrew and a large number of the French protested by abstaining, thus

assuring a decisive victory for his African Bloc. In

October 1945, Houphouët moved onto the national political scene;

the French government decided to represent its colonies in the assemblée constituante (English: Constituent Assembly) and gave Côte d'Ivoire and Upper Volta two

representatives in Parliament combined. One of these would represent

the French citizens and another would represent the indigenous

population, but the suffrage was limited to less than 1% of the population. In

an attempt to block Houphouët, the governor de Mauduit supported a

rival candidature, and provided him the full backing of the

administration. Despite that and thanks to the SAA's strong

organization, Houphouët, running for the indigenous seat, easily

came first with a 1,000-vote majority. He failed, however, to obtain an absolute majority, due to the large number of candidates running. Houphouët

emerged victorious again in the second round of elections held on 4

November 1945, in which he narrowly defeated an Upper Voltan candidate

with 12,980 votes out of a total of 31,081. At this point, he decided to add "Boigny" to his surname, meaning "irresistible force" in Baoulé and symbolizing his role as a leader. In taking his seat at the National Assembly in Palais Bourbon, Houphouët - Boigny had first thing to decide with which group to side, and he opted for the Mouvement Unifié de la Résistance (MUR), a small party composed of Communist sympathizers but not formal members of the Communist Party. He was appointed a member of the Commission des territoires d'outre-mer (Commission of Overseas Territories). During

this time, he worked to implement the wishes of the SAA, in particular

proposing a bill to abolish forced labor — the single most unpopular

feature of French rule. The Assembly adopted this bill, known as Loi Houphouët - Boigny, on 11 April 1946, greatly enhancing the author's prestige not only in his country. On

3 April 1946, Houphouët - Boigny proposed to unify labour

regulations in the territories of Africa; this would eventually be

completed in 1952. Finally, on 27 September 1946, he filed a report on

the public health system

of overseas territories, calling for its reformation.

Houphouët - Boigny in his parliamentary tenure supported the idea of

a union of French territories. Such a union would, in his view, create a policy that was "métropolitaine et démocratique" (metropolitan and democratic), the other "coloniale et réactionnaire" (colonial and reactionary). As the first constitution proposed by the Constituent Assembly was rejected by the voters, new elections were held in 1946 for a second constituent assembly. For these elections Houphouët - Boigny organized on 9 April 1946, with the help of the Groupes d'études communistes (English: Communist Study Groups), the Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire (PDCI),

whose structure closely followed that of the SAA. It immediately became

the first successful independent African party when the new party

Houphouët - Boigny easily swept the elections with 21,099 out of

37,888 votes, his opponents obtaining only a few hundred votes each. In this he was helped by the recall of Governor Latrille, whose predecessor had been fired by the Overseas Minister Marius Moutet for his opposition to the abolition of the indigénat. With his return to the assembly he was appointed to the Commission du règlement et du suffrage universel (Commission

for Regulation of Universal Suffrage); as secretary of the commission

from 1947 to 1948, he proposed on 18 February 1947 to reform French West Africa (AOF), French Equatorial Africa (AEF),

and the French territories' federal council to better represent the

African peoples. He also called for the creation of local assemblies in

Africa so that Africans could learn how to be autonomous. During

the holding of the second Constituent Assembly the African

representatives witnessed a strong reaction against the colonial

liberalism that had been embedded in the rejected constitution drafted

by the previous assembly. The new text, approved by the voters on

October 13, 1946, reduced the African representatives from 30 to 24,

and reduced the number of those entitled to vote; also, a large number

of colonial topics were left in which the executive could govern by

decree, and supervision over the colonial administration remained weak. Reacting to what they felt was a betrayal of the MRP's and the Socialists'

promises, the African deputies concluded they needed to build a

permanent coalition independent from the French parties.

Houphouët - Boigny was the first to propose this to his African

colleagues, and obtained their full support for a founding congress to

be held in October at Bamako in French Sudan. The

French government did all it could to sabotage the congress, and in

particular the Socialist Overseas Minister was successful in persuading

the African Socialists, who were originally among the promoters, from

attending. This ultimately backfired, radicalizing those convened; when they founded the African Democratic Rally (RDA) as an inter - territorial political movement, it was the pro-Communist Gabriel d'Arboussier who dominated the congress. The

new movement's goal was to free "Africa from the colonial yoke by the

affirmation of her personality and by the association, freely agreed

to, of a union of nations". Its first president, confirmed several

times subsequently, was Houphouët - Boigny, while secretary general became d'Arboussier. As part of the bringing of the territorial parties in the organization, the PDCI became the Ivoirian branch of the RDA. Too small to form their own parliamentary group, the African deputies were compelled to join one of the larger parties in order to sit together in the Palais Bourbon. Thus, the RDA soon joined the French Communist Party (PCF) as the only openly anti - colonialist political faction and soon organised strikes and boycotts of European imports. Houphouët - Boigny

justified the alliance because it seemed, at the time, to be the only

way for his voice to be heard: "Even before the creation of RDA, the

alliance had served our cause: in March 1946, the abolition of

compulsory labour was adopted unanimously, without a vote, thanks to

our tactical alliance." As the Cold War set

in, the alliance with the Communists became increasingly damaging for

the RDA. The French colonial administration showed itself increasingly

hostile toward the RDA and its president, whom the administration

called a "Stalinist". Tensions reached their height at the beginning of 1950, when, following an outbreak of anti - colonial violence, almost the entire PDCI leadership was arrested; Houphouët - Boigny managed to slip away shortly before police arrived at his house. Although Houphouët - Boigny would have been saved by his parliamentary immunity, his missed arrest was popularly attributed to his influence and his prestige. In the ensuing chaos, riots broke out in Côte d'Ivoire; the

most significant of which was a clash with the police at Dimbokro in

which 13 Africans were killed and 50 wounded. According to official

figures, by 1951 a total of 52 Africans had been killed, several

hundred wounded and around 3,000 arrested (numbers which, according to

an opinion reported by journalist Ronald Segal in African Profiles, are certainly underestimated). In order to defuse the crisis, Prime Minister René Pleven entrusted the France's Minister for Overseas Territories,François Mitterrand, with the task of detaching the RDA from the PCF, and

in fact an official alliance between the RDA and Mitterrand's party,

the UDSR, was established in 1952. Knowing he was at an impasse, in

October 1950, Houphouët - Boigny agreed to break the Communist

alliance. Asked

in an undated interview why he worked with the communists,

Houphouët - Boigny replied: "I, a bourgeois landowner, I would

preach the class struggle? That is why we aligned ourselves with the

Communist Party, without joining it." In the 1951 elections, the number of seats was reduced from three to two; while Houphouët - Boigny still won a seat, the other RDA candidate, Ouezzin Coulibaly,

did not. All in all, the RDA only garnered 67,200 of 109,759 votes in

that election, and the party in direct opposition to it captured a

seat. On 8 August 1951, Boigny, speaking at René Pleven's

inauguration as president of the board, denied being the leader of a

communist group; he was not believed until the RDA's 1952 affiliation

with UDSR. On the 24th of that same month, Boigny delivered a statement

in the Assembly contesting the result of the elections, which he

declared tainted by fraud. He also denounced what he saw as the

exploitation of overseas deputies as "voting machines", who, as

political pawns, supported the colonial government's every action. Thereafter, Houphouët - Boigny and the RDA were briefly unsuccessful before their success was renewed in 1956; at that year's elections,

the party received 502,711 of 579,550 votes cast. From then on, his

relationship with Communism was forgotten, and he was embraced as a

moderate. Named as a member of the Committees on Universal Suffrage

(distinct from the aforementioned committee regulating said

suffrage), Constitutional Laws, Rules and Petitions. On 1 February

1956, he was appointed Minister Discharging the Duties of the

Presidency of the Council in the government of Guy Mollet,

a post he held until 13 June 1957. This marked the first time an

African was elected to a leading position in the French colonies'

governments. His principal achievement in this role was the creation of

an organisation of Saharan regions that would help ensure

sustainability for the French Union and counter Moroccan territorial claims in the Sahara. On 6 November 1957, Houphouët - Boigny became Minister of Public Health and Population in the Gaillard administration and attempted to reform the public health code. He had previously served as Minister of State under Maurice Bourgès - Maunoury (13 June – 6 November 1957). Following his Gaillard ministry, he was again appointed Minister of State from 14 May 1958 – 20 May 1959. In

this capacity, he participated in the development of France's African

policy, notably in the cultural domain. At his behest, the Bureau of

French Overseas Students and the University of Dakar were created. On 4 October 1958, Houphouët - Boigny was one of the signatories, along with de Gaulle, of the Constitution of the Fifth Republic. The

last post he held in France was Minister - Counsellor in the Michel

Debré government, from 23 July 1959 to 19 May 1961. Until the mid 1950s, French colonies in west and central Africa were grouped within two federations: French Equatorial Africa (AEF) and French West Africa (AOF). Côte d'Ivoire was part of the AOF, financing roughly two thirds of its budget. Wishing to liberate the country from the guardianship of the AOF, Houphouët - Boigny

advocated an Africa made up of nations that would generate wealth

rather than share poverty and misery. He participated actively in the

drafting and adoption of the framework of the Defferre Loi Cadre,

a French legal reform which, in addition to granting autonomy to

African colonies, would break the ties that bound the different

territories together, giving them more autonomy by means of local

assemblies. The Deffere Loi Cadre was far from unanimously accepted by Houphouët - Boigny's compatriots in Africa: Léopold Sédar Senghor, leader of Senegal, was the first to speak out against this attempted "Balkanization"

of Africa, arguing that the colonial territories "do not correspond to

any reality: be it geographical, economic, ethnic, or linguistic".

Senghor argued that maintaining the AOF would give the territories

stronger political credibility and would allow them to develop

harmoniously as well as emerge as a genuine people. This view was shared by most members of the African Democratic Rally, who backed Ahmed Sékou Touré and Modibo Keïta, placing Houphouët - Boigny in the minority at the 1957 congress in Bamako. Following

the adoption of the Loi Cadre reform on 23 June 1956, a territorial

election was held in Côte d'Ivoire on 3 March 1957, in which the

PDCI — transformed under Houphouët - Boigny's firm control into a

political machine — won many seats. Houphouët - Boigny, who was already serving as a minister in France, as President of the Territorial Assembly and as mayor of Abidjan, chose Auguste Denise to serve as Vice President of the Government Council of Côte d'Ivoire, even though Houphouët - Boigny remained, the only interlocutor in the colony for France. Houphouët - Boigny's

popularity and influence in France's African colonies had become so

pervasive that one French magazine claimed that by 1956, the

politician's photograph "was in all the huts, on the lapels of coats,

on the corsages of African women and even on the handlebars of

bicycles". On 7 April 1957, the Prime Minister of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, on a visit to Côte d'Ivoire, called on all colonies in Africa to declare their independence; Houphouët - Boigny retorted to Nkrumah: Unlike

many African leaders who immediately demanded independence,

Houphouët - Boigny wished for a careful transition within the "ensemble français" because, according to him, political independence without economic independence was worthless. He

also invited Nkrumah to meet up with him in 10 years to see which one

of the two had chosen the best approach toward independence. On 28 September 1958 Charles de Gaulle proposed a constitutional referendum to the Franco - African community:

the territories were given the choice of either supporting the

constitution or proclaiming their independence and being cut off from

France. For

Houphouët - Boigny, the choice was simple: "Whatever happens,

Côte d'Ivoire will enter directly to the Franco - African

community. The other territories are free to group between themselves

before joining." Only Guinea chose

independence; its leader, Ahmed Sékou Touré, opposed

Houphouët - Boigny, stating that his preference was "freedom in

poverty over wealth in slavery". The referendum produced the French Community,

an institution meant to be an association of free republics which had

jurisdiction over foreign policy, defense, currency, common ethnic and

financial policy, and strategic raw materials. Houphouët - Boigny was determined to stop the hegemony of

Senegal in West Africa and a political confrontation ensued between

Ivorian and Senegalese leaders. Houphouët - Boigny refused to

participate in the Inter-African conference in Dakar on 31 December 1958, which was intended to lay the foundation for the Federation of Francophone African States. Although that federation was never realised, Senegal and Mali (known at the time as French Sudan) formed their own political union, the Mali Federation.

After de Gaulle allowed the Mali Federation independence in 1959,

Houphouët - Boigny tried to sabotage the federation's efforts to

wield political control; in cooperation with France, he managed to convince Upper Volta, Dahomey, and Niger to withdraw from the Mali Federation, before it collapsed in August 1960. Two

months after the 1958 referendum, seven member states of French West

Africa, including Côte d'Ivoire, became autonomous republics

within the French Community. Houphouët - Boigny had won his first

victory against those supporting federalism.

This victory established the conditions that made the future "Ivorian

miracle" possible, since between 1957 and 1959, budget revenues grew by

158%, reaching 21,723,000,000 CFA francs.

Houphouët - Boigny

officially became the head of the government of Côte d'Ivoire on

1 May 1959. Although he faced no opposition from rival parties and the

PDCI became the de facto party of the state in 1957, he was confronted by opposition from his own government. Radical nationalists, led by Jean - Baptiste Mockey, openly opposed the government's Francophile policies. In

an attempt to solve this problem, Houphouët - Boigny decided to

exile Mockey in September 1959, claiming that Mockey had attempted to

assassinate him using voodoo in what Houphouët - Boigny called the "complot du chat noir" (black cat conspiracy). Houphouët - Boigny

began drafting a new constitution for Côte d'Ivoire after the

country's independence from France on 7 August 1960. It drew heavily from the United States Constitution in establishing a powerful executive branch, and from the Constitution of France, which limited the capacities of the legislature. He

transformed the National Assembly into a mere recording house for bills

and budget proposals; the representatives were to be appointed by the

head of government, and the PDCI was to act like an intermediary

between the people and the government. On 27 November 1960, Houphouët - Boigny was elected unopposed to the Presidency of the Republic, while the list of candidates of the PDCI — the only participating party — was approved for the National Assembly. 1963

was marked by a series of alleged plots that played a decisive role in

ultimately consolidating power in the hands of Houphouët - Boigny.

There is no clear consensus on the unfolding of the 1963 events; in

fact, there may have been no plot at all and the entire series of

events may have been part of a plan by Houphouët - Boigny to

consolidate his hold on power. Between 120 and 200 secret trials were

held in Yamoussoukro, in which key political figures — including Mockey

and the president of the Supreme Court Ernest Boka — were implicated. There was discontent in the army, as the generals grew restive following the arrest of Defense Minister Jean Konan Banny, and the president had to intervene personally to pacify them. From then on, Houphouët - Boigny governed Côte d'Ivoire as a dictator. Nevertheless, once he had consolidated his power, he freed political prisoners in 1967. Under

his "unique brand of paternalistic authoritarianism", Houphouët - Boigny subdued dissent by offering government positions

instead of incarceration to his critics. According to Robert Mundt, author of Côte d'Ivoire: Continuity and Change in a Semi-Democracy, his power was never seriously challenged from 1963 until his death. In order to foil any plans for a coup d'etat, the president took control of the military and police, reducing their numbers from 5,300 to 3,500. Defence

was entrusted to the French armed forces that, pursuant to the treaty

on defence cooperation of 24 April 1961, were stationed at Port - Bouët and could intervene at Houphouët - Boigny's request or when they considered French interests to be threatened. They subsequently intervened during attempts by the Sanwi monarchists to secede in 1959 and 1969, and

again in 1970, when an unauthorised political group, the Eburnian

Movement, was formed and Houphouët - Boigny accused its leader

Kragbé Gnagbé of wishing to secede.

Houphouët - Boigny married the much younger Marie - Thérèse Houphouët - Boigny in 1962, having divorced his first wife in 1952. The couple had no children of their own, but they adopted two: five year old Hélène in

1960, the granddaughter of King Baoulé Anoungbré, and

Olivier Antoine in 1981. The marriage was not without scandal: in 1958,

Marie - Thérèse went on a romantic escapade in Italy, while in 1961, Houphouët - Boigny fathered a child (Florence, d. 2007) out of wedlock by his mistress Henriette Duvignac. Following

the example of de Gaulle, who refused proposals for an integrated

Europe, Houphouët - Boigny opposed Nkrumah's proposed United States of Africa,

which called into question Côte d'Ivoire's recently acquired

national sovereignty. However, Houphouët - Boigny was not against

African unity which developed on a case by case basis. On 29 May 1959, in cooperation with Hamani Diori (Niger), Maurice Yaméogo (Upper Volta) and Hubert Maga (Dahomey), Houphouët - Boigny created the Conseil de l'Entente (English: Council of Accord or Council of Understanding). This

regional organisation, founded in order to hamper the Mali Federation,

was designed with three major functions: to allow shared management of

certain public services, such as the port of Abidjan or the

Abidjan – Niger railway line; to provide a solidarity fund accessible to

member countries, 90% of which was provided by Côte d'Ivoire; and

to provide funding for various development projects through

low-interest loans to member states (70% of the loans were supplied by

Côte d'Ivoire). In 1966, Houphouët - Boigny even offered to grant dual citizenship to

nationals from member countries of the Conseil de l'Entente, but the

proposition was quickly abandoned following popular protests. The

ambitious Ivorian leader had even greater plans for French speaking

Africa: he intended to rally the different nations behind a large

organisation whose objective was the mutual assistance of its member

states. The project became a reality on 7 September 1961 with the signing of a charter giving birth to the l’Union africaine et malgache (UAM; English: African and Malagasy Union), comprising 12 French speaking countries including Léopold Sédar Senghor's

Senegal. Agreements were signed in various sectors, such as economic,

military and telecommunications, which strengthened solidarity among

Francophone states. However, the creation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in May 1963 affected his plans: the supporters of Pan-Africanism demanded

the dissolution of all regional groupings, such as the UAM.

Houphouët - Boigny reluctantly ceded, and transformed the UAM into

the Organisation africaine et malgache de coopération économique et culturelle (English: African and Malagasy Organization of economic and cultural cooperation). Considering the OAU a dead end organisation, particularly since Paris was opposed to the group, Houphouët - Boigny decided to create in 1965 l’Organisation commune africaine et malgache (OCAM; English: African and Malagasy Organization),

a French organization in competition with the OAU. The organisation

included among its members 16 countries, whose aim was to break

revolutionary ambitions in Africa. However, over the years, the organisation became too subservient to France, resulting in the departure of half of the countries. In

the mid 1970s, during times of economic prosperity,

Houphouët - Boigny and Senghor put aside their differences and

joined forces to thwart Nigeria, which, in an attempt to established

itself in West Africa, had created the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The two countered the ECOWAS by creating the Economic Community of West

Africa (ECWA), which superseded the old trade partnerships in the

French speaking regions. However,

after assurances from Nigeria that ECOWAS would function in the same

manner as the earlier Francophone organisations, Houphouët - Boigny

and Senghor decided to merge their organization into ECOWAS in May 1975.

Throughout

his presidency, Houphouët - Boigny surrounded himself with French

advisers, such as Guy Nairay, Chief of Staff from 1960 to 1993, and

Alain Belkiri, Secretary - General of the Ivorian government, whose

influence extended to all areas. This type of diplomacy, which he labelled "Françafrique",

allowed him to maintain very close ties with the former colonial power,

making Côte d'Ivoire France's primary African ally. Whenever one

country would enter an agreement with an African nation, the other

would unconditionally give its support. Through this arrangement,

Houphouët - Boigny built a close friendship with Jacques Foccart, the chief adviser on African policy in the de Gaulle and Pompidou governments. By claiming independence for Guinea through the 28 September 1958 French constitutional referendum, Ahmed Sékou Touré had not only defied de Gaulle, but also his fellow African, Houphouët - Boigny. He distanced himself from Guinean officials in Conakry and the Guinean Democratic Party was excluded from the RDA. Tensions

between Houphouët - Boigny and Touré also began to rise due

to the conspiracies of the French intelligence agency SDECE against the Sékou Touré regime. In January 1960, Houphouët - Boigny delivered small arms to former rebels in Man, Côte d'Ivoire and incited his council in 1965 to agree to taking part in an attempt to overthrow Sékou Touré. In 1967, he promoted the creation of the Front national de libération de la Guinée (FNLG; English: National Front for the Liberation of Guinea), a reserve of men ready to plot the downfall of Sékou Touré. Houphouët - Boigny's relationship with Kwame Nkrumah, the leader of neighboring Ghana,

degraded considerably following Guinea's independence, due to Nkrumah's

financial and political support for Sékou Touré. After

Sékou Touré convinced Nkrumah to support the secessionist

Sanwi in Côte d’Ivoire, Houphouët - Boigny began a campaign

to

discredit the Ghanaian regime. He accused Nkrumah of trying to destabilise Côte d'Ivoire in 1963, and called for the Francophone states to boycott the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) conference scheduled to take place in Accra. Nkrumah was ousted from power in 1966 in a military coup;

Houphouët - Boigny allowed the conspirators to use Côte

d'Ivoire as a base to coordinate the arrival and departure of their

missions. Also

in collaboration with Foccart, Houphouët - Boigny took part in the

attempted coup of 16 January 1977 led by famed French mercenary Bob Denard against the revolutionary regime of Mathieu Kérékou in Dahomey. Houphouët - Boigny, in order to fight against the Marxistsin power in Angola, also lent his support to Jonas Savimbi's UNITA party, whose feud with the MPLA party led to the Angolan Civil War. Despite his reputation as a destabaliser of regimes, Houphouët - Boigny granted refuge to Jean - Bedel Bokassa, after the exiled Central African Republic dictator had been overthrown by French paratroopers in

September 1979. This move was met with international criticism, and

thus, having become a political and financial burden to

Houphouët - Boigny, Bokassa was expelled from Côte d'Ivoire in

1983. Houphouët-Boigny was a participant in the November 1960 Congo Crisis, during which the United Nations tried to remove Congo - Kinshasa from the influence of the revolutionary Marxist Patrice Lumumba. The Ivorian leader supported President Joseph Kasa - Vubu, an opponent of Lumumba, and followed France in supporting the controversial Congolese Prime Minister Moise Tshombe. Tshombe,

disliked by much of Africa, was passionately defended by

Houphouët - Boigny and was even invited into OCAM in May 1965. After the overthrow of Kasa - Vubu by General Mobutu in November 1965, the Ivorian president supported, in 1967, a plan proposed by the French secret service which

aimed to bring the deposed Congolese leader back into power. The

operation was a failure. In response, Houphouët - Boigny decided to

boycott the fourth annual summit of the OAU held in September 1967 in Kinshasa. Houphouët - Boigny was also a major contributor to the political tensions in Biafra.

Considering Nigeria a potential danger to French influenced African

states, Foccart sent Houphouët - Boigny and Lieutenant Colonel

Raymond Bichelot on a mission in 1963 to monitor political developments

in the country. The opportunity to weaken the former British colony presented itself in May 1967, when Biafra, led by Lieutenant Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, undertook to secede from

Nigeria. French aligned African countries supported the secessionists

who, provided with mercenaries and weapons by Jean

Mauricheau - Beaupré, began a civil war. By

the end of the 1960s, French supported nations suddenly and openly

distanced themselves from France and Côte d'Ivoire's position on

the civil war. Isolated on the international scene, both countries decided to suspend their

assistance to Ojukwu, who eventually went into exile in Côte

d'Ivoire. At the request of Paris, Houphouet - Boigny began forging relations with South Africa in

October 1970, justifying his attitude by stating that "[t]he problems

of racial discrimination, so painful, so distressing, so revolting to

our dignity of Negros, must not be resolved, we believe, by force." He

even proposed to the OAU in June 1971 that they follow his lead. In

spite of receiving some support, his proposal was rejected. This

refusal did not, however, prevent him from continuing his attempts to

approach the Pretoria regime.

His attempts bore fruit in October of that year, when a semi-official

meeting between a delegation of high level Ivorian officials and South

African Prime Minister B.J. Vorster was held in the capital of South Africa. Moreover, mindful of the Communist influence in Africa, he met Vorster in Geneva in 1977, after the Soviet Union and Cuba tried to collectively spread their influence in Angola and Ethiopia. Relations with South Africa continued on an official basis until the end of his presidency. Houphouët - Boigny and Thomas Sankara, the leader of Burkina Faso,

had a highly turbulent relationship. Tensions reached their climax in

1985 when Côte d'Ivoire Burkinabés accused authorities of

being involved in a conspiracy to forcibly recruit young students to

training camps in Libya. Houphouët - Boigny

responded by inviting the dissident Jean - Claude Kamboulé to take

refuge in Côte d'Ivoire so that he could organise opposition to

the Sankara regime. In 1987, Sankara was overthrown and assassinated in

a coup. The coup may have had French involvement, since the Sankara regime had fallen into disfavour in France. Houphouët - Boigny

was also suspected of involvement in the coup and in November, the PDCI

asked the government to ban the sale of Jeune Afrique following its allegations that Houphouët - Boigny had participated in the coup. The Ivorian president would have greatly benefited from the divisions in the Burkina Faso government, so he contacted Blaise Compaoré, the second most powerful man in the regime. It is believed that they worked in conjunction with the President of France François Mitterrand, Laurent Dona Fologo, Robert Guéï and Pierre Ouédraogo to overthrow the Sankara regime. Besides

supporting policies pursued by France, Houphouët - Boigny also

influenced their actions in Africa. He pushed France to support and provide arms to warlord Charles Taylor's rebels during the First Liberian Civil War in hopes of receiving some of the country's assets and resources after the war. From the time of Côte d'Ivoire's independence, Houphouët - Boigny considered the Soviet Union and China "malevolent" influences on developing countries. He did not establish diplomatic relations with Moscow until 1967 and then severed them in 1969 following allegations of direct Soviet support to a 1968 student protest at the National University of Côte d'Ivoire. The two countries did not restore ties until February 1986, by

which time Houphouët - Boigny had embraced a more active foreign

policy reflecting his quest for greater international recognition. Houphouët - Boigny

was even more outspoken in his criticism of the People's Republic of

China (PRC). He voiced fears of an "invasion" by the Chinese and a

subsequent colonisation of Africa. He was especially concerned that

Africans would see the problems of development in China as analogous to

those of Africa, and see China's solutions as appropriate to sub-Saharan Africa. Accordingly, Côte d'Ivoire was one of the last countries to normalise relations with China, doing so on 3 March 1983. Under the principle demanded by Beijing for "one China", the recognition by Côte d'Ivoire of the PRC effectively disestablished diplomatic relations between Abidjan and Taiwan. Houphouët - Boigny adopted a system of economic liberalism in

Côte d'Ivoire in order to obtain the trust and confidence of

foreign investors, most notably the French. The advantages granted by

the investment laws he established in 1959 allowed foreign business to

repatriate up to 90% of their profits in their country of origin (the

remaining 10% was reinvested in Côte d'Ivoire). He

also developed an agenda for modernising the country's infrastructure,

for example, building an American style business district in Abidjan

where five-star hotels and resorts welcomed tourists and businessmen.

Côte d'Ivoire experienced economic growth of 11 – 12% from 1960 to

1965. The country's gross domestic product (GDP) grew twelvefold between 1960 and 1978, from 145 to 1,750 billion CFA francs, while the trade balance continued to record a surplus. The origin of this economic success stemmed from the president's decision to focus on the primary sector of the economy, rather than the secondary sector. As

a result, the agricultural sector experienced significant development:

between 1960 and 1970, cocoa cultivators tripled their production to

312,000 tonnes and coffee production rose by nearly 50%, from 185,500 to 275,000 tonnes. As

a result of this economic prosperity, Côte d'Ivoire saw an influx

of immigrants from other West African countries; the foreign

workforce — mostly Burkinabés — who maintained indigenous

plantations, represented over a quarter of the Ivorian population by

1980. Both

Ivorians and foreigners began referring to Houphouët - Boigny as the

"Sage of Africa" for performing what became known as "Ivorian miracle".

He was also respectfully nicknamed "The Old One" (Le Vieux). However,

the economic system developed in cooperation with France was far from

perfect. As Houphouët - Boigny described it, the economy of

Côte d'Ivoire experienced "growth without development". The

growth of the economy depended on capital, initiatives and a financial

framework from investors abroad; it had not become independent or

self-sustaining. Beginning

in 1978, the economy of Côte d'Ivoire experienced a serious

decline due to the sharp downturn in international market prices of coffee and cocoa. The

decline was perceived as fleeting, since its impact on planters was

buffered by the Caistab, the agricultural marketing board, which ensured them a livable income. The

next year, in order to contain a sudden drop in the prices of exported

goods, Houphouët - Boigny raised prices to resist international tariffs on

raw materials. However, by applying only this solution, Côte

d'Ivoire lost more than 700 billion CFA francs between 1980 and 1982.

From 1983 to 1984, Côte d’Ivoire fell victim to a drought that

ravaged nearly 400,000 hectares of forest and 250,000 hectares of coffee and cocoa plants. To

address this problem, Houphouët - Boigny travelled to London to

negotiate an agreement on coffee and cocoa prices with traders and

industrialists; by 1984, the agreement had fallen apart and Côte

d'Ivoire was engulfed in a major financial crisis. Even the production of the offshore oil drilling and petrochemical industries,

developed to supply the Caistab, was affected by the 1986 worldwide

economic recession. Côte d'Ivoire, which had bought planters'

harvests for double the market price, fell into heavy debt. By May 1987, the foreign debt had reached US$10 billion, prompting

Houphouët - Boigny to suspend payments of the debt. Refusing to sell

off its supply of cocoa, the country shut down its exports in July and

forced world rates to increase. However, this "embargo" failed. In

November 1989, Houphouët - Boigny liquidated his enormous stock of

cocoa to big businesses to jumpstart the economy. Gravely ill at this

time, he named a Prime Minister (the post was unoccupied since 1960), Alassane Ouattara, who established a series of belt tightening economic measures to bring the country out of debt. The

general atmosphere of enrichment and satisfaction during the period of

economic growth in Côte d'Ivoire made it possible for

Houphouët - Boigny to maintain and control internal political

tensions; his

easygoing dictatorship, where political prisoners were almost

nonexistent, was well accepted by the population. However, the economic

crisis that began in the 1980s caused a sharp decline in living

conditions for the middle class and underprivileged urban populations. According to the World Bank, the population living below the poverty threshold went

from 11% in 1985 to 31% by 1993. Despite the implementation of certain

measures, such as the reduction of the number of young French workers

(who worked abroad while serving in the military) from 3,000 to 2,000

in 1986, allowing many jobs to go to young Ivorian graduates, the

government failed to control the rising rates of unemployment and

bankruptcy in many companies. Strong social agitations shook the country, creating insecurity. The army mutinied in

1990 and 1992, and on 2 March 1990, protesters organized mass

demonstrations in the streets of Abidjan with slogans such as "thief

Houphouët" and "corrupt Houphouët". These popular demonstrations prompted the president to launch a system of democratization on 31 May, in which he authorised political pluralism and trade unions. Laurent Gbagbo gained

recognition as one of the principal instigators of the student

demonstrations during the protests against Houphouët - Boigny's

government on 9 February 1982, which led to the closing of the

universities and other educational institutions. Shortly thereafter,

his wife and he formed what would become the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI).

Gbagbo went into exile in France later that year, where he promoted the

FPI and its political platforms. Although the FPI was ideologically

similar to the Unified Socialist Party,

the French socialist government tried to ignore Gbagbo's party to

please Houphouët - Boigny. After a lengthy appeal process, Gbagbo

obtained status as a political refugee in France in 1985. However,

the French government attempted to pressure him into returning to

Côte d'Ivoire, as Houphouët - Boigny had begun to worry about

Gbagbo's developing a network of contacts, and believed "his stirring

opponent would be less of a threat in Abidjan than in Paris". In

1988, Gbagbo returned from exile to Côte d'Ivoire after

Houphouët - Boigny implicitly granted him forgiveness by declaring

that "the tree did not get angry at the bird". On

28 October 1990, a presidential election was held, which for the first

time featured a candidate other than Houphouët - Boigny: Gbagbo. He

highlighted the President's age, suggesting that he was too old for a

seventh five-year term. Houphouët - Boigny

countered by broadcasting television footage of his youth, and he was

re-elected to a seventh term with 2,445,365 votes to 548,441. During

his presidency, Houphouët-Boigny benefited greatly from the wealth

of Côte-d’Ivoire; by the time of his death in 1993, his personal

wealth was estimated to be between US$7 and $11 billion. With

regards to his large fortune, Houphouët - Boigny said in 1983,

"People are surprised that I like gold. It's just that I was born in

it." The Ivorian leader acquired a dozen properties in the metropolitan area of Paris (including Hotel Masseran on Masseran Street in the 7th arrondissement of Paris), a property in Castel Gandolfo in Italy, and a house in Chêne-Bourg, Switzerland.

He owned real estate companies, such as Grand Air SI, SI Picallpoc and

Interfalco, and had many shares in prestigious jewelry and watchmaking

companies, such as Piaget SA and Harry Winston.

He placed his fortune in Switzerland, once asking if "there is any

serious man on Earth not stocking parts of his fortune in Switzerland". In 1983, Houphouët - Boigny moved the capital from Abidjan to Yamoussoukro. There,

at the expense of the state, he built many buildings such as the

Institute Polytechnique and an international airport. The most

luxurious project was the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace, which is currently the largest church in the world, with an area of

30,000 square metres (320,000 sq ft) and a height of

158 metres (518 ft). Personally financed by Houphouët - Boigny, construction for the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace was carried out by the Lebanese architect Pierre Fakhoury at a total cost of about US$150 – 200 million. Houphouët - Boigny offered it to Pope John Paul II as a "personal gift"; the latter, after having unsuccessfully requested it being shorter than St. Peter's in Rome, consecrated it all the same on 10 September 1990. Due

to a collapse of the national economy coupled with lavish amounts spent

on its construction, the Basilica was criticized: it was called "the

basilica in the bush" by several western news agencies. The

political, social, and economic crises also touched the issue of who

would succeed Houphouët - Boigny as head of state. After severing ties with his former political heir Philippe Yacé in

1980, who, as president of the National Assembly, was entitled to

exercise the full functions of President of the Republic if the Head of

State was incapacitated or absent, Houphouët - Boigny

delayed as much as he could in officially designating a successor. The

president's health became increasingly fragile, with Prime Minister Alassane Ouattara administering the country from 1990 onwards, while the president was hospitalised in France. There was a struggle for power, which ended when Houphouët - Boigny rejected Ouattara in favour of Henri Konan Bédié, the President of the National Assembly. In December 1993, Houphouët - Boigny, terminally ill with prostate cancer, was urgently flown back to Côte d'Ivoire so he could die there. He was kept on life support to

ensure that the last dispositions concerning his succession were

defined. After his family consented, Houphouët - Boigny was

disconnected from life support at 6:35 A.M. GMT on 7 December. At the time of his death, Houphouët - Boigny was the longest serving leader in Africa and the third in the world, after Fidel Castro of Cuba and Kim Il Sung of North Korea. Houphouët - Boigny

left no written will or legacy report for Côte d’Ivoire upon his

death in 1993. His recognised heirs, especially Helena, led a battle

against the government to recover part of the vast fortune

Houphouët - Boigny had left, which she claimed was "private" and did not belong to the State. Following

Houpouët-Boigny's death, the country's stability was maintained,

as seen by his impressive funeral on 7 February 1994. The funeral for this "doyen of francophone Africa" was

held in the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace, with 7,000 guests inside the

building and tens of thousands outside. The two month delay before

Houpouët - Boigny's funeral, common among members of the Baoule

ethnic group, allowed for many ceremonies preceding his burial. The

president's funeral featured many traditional African funerary customs,

including a large chorus dressed in bright batik dresses singing

"laagoh budji gnia" (Baoulé: "Lord, it is you who has made all things") and village chiefs displaying strips of kente and

korhogo cloth. Baoulés are traditionally buried with objects

they enjoyed while alive; Houpouët - Boigny's family, however, did

not state what, if anything, they would bury with him. Over 140 countries and international organisations sent delegates to the funeral. However, according to The New York Times,

many Ivorians were disappointed by the poor attendance of several key

allies, most notably the United States. The small United States

delegation was led by Secretary of Energy Hazel R. O'Leary and Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs George Moose. In contrast, Houphouët - Boigny's close personal ties with France were reflected in the large French delegation, which included President François Mitterrand; Prime Minister Édouard Balladur; the presidents of the National Assembly and of the Senate, Philippe Séguin and René Monory; former President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing; Jacques Chirac; his friend Jacques Foccart; and six former Prime Ministers. According to The New York Times,

"Houphouët - Boigny's death is not only the end of a political era

here, but perhaps as well the end of the close French - African

relationship that he came to symbolize."

To establish his legacy as a man of peace, Houphouët - Boigny created an award in 1989, sponsored by UNESCO and funded entirely by extra - budgetary resources provided by the Félix - Houphouët - Boigny Foundation, to

honor those who search for peace. The prize is "named after President

Félix Houphouët - Boigny, the doyen of African Heads of State

and a tireless advocate of peace, concord, fellowship and dialogue to

solve all conflicts both within and between States". It is awarded annually along with a check for €122,000, by an international jury composed of 11 persons from five continents, led by former United States Secretary of State and Nobel Peace Prize winner Henry Kissinger. The prize was first awarded in 1991 to Nelson Mandela, president of the African National Congress, and Frederik Willem de Klerk, president of the Republic of South Africa, and has been awarded each year since, with the exception of 2001 and 2004.

In 1930, Houphouët married Kady Racine Sow (1913 – 2006) in Abengourou despite the fact that he was a practising Catholic, and she was the daughter of a wealthy Muslim from Senegal. The

families of the two eventually overcame their opposition and accepted

the interfaith union, the first ever celebrated in Côte d'Ivoire. The couple had five children: Felix (who died in infancy), Augustine, Francis, Guillaume and Marie, all raised as Catholics.