<Back to Index>

- Mathematician René Frédéric Thom, 1923

- Writer Paul Charles Joseph Bourget, 1852

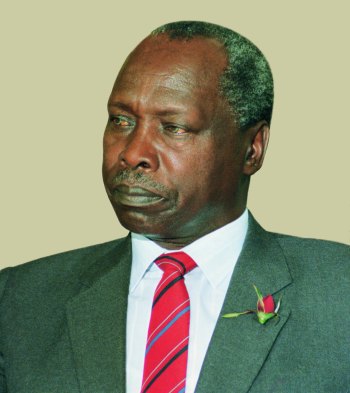

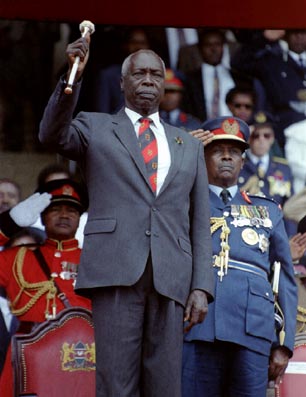

- 2nd President of Kenya Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, 1924

PAGE SPONSOR

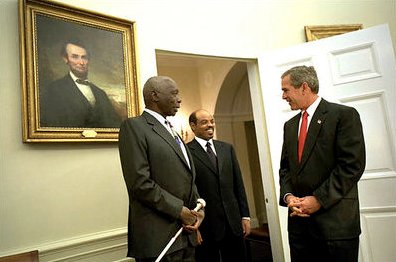

Daniel Toroitich arap Moi (born 2 September 1924) was the President of Kenya from 1978 until 2002.

Daniel arap Moi is popularly known to Kenyans as 'Nyayo', a Swahili word for 'footsteps'. He was following the footsteps of the first Kenyan President, Jomo Kenyatta. Moi was born in Kurieng'wo village, Sacho division, Baringo District, Rift Valley Province,

and was raised by his mother Kimoi Chebii following the early death of

his father. After completing his secondary education, he attended Tambach Teachers Training College in the Keiyo District. He worked as a teacher from 1946 until 1955. In 1955 Moi entered politics when he was elected Member of the Legislative Council for Rift Valley. In 1960 he founded the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) with Ronald Ngala to challenge the Kenya African National Union (KANU)

led by Jomo Kenyatta. KADU pressed for a federal constitution, while

KANU was in favour of centralism. The advantage lay with the

numerically stronger KANU, and the British government was finally

forced to remove all provisions of a federal nature from the

constitution. In

1957 Moi was re-elected Member of the Legislative Council for Rift

Valley. He became Minister of Education in the pre-independence government of 1960 – 1961. After

Kenya gained independence on December 12, 1963, Kenyatta convinced Moi

that KADU and KANU should be merged to complete the process of

decolonisation. Kenya therefore became a de facto single party state, dominated by the Kĩkũyũ-Luo alliance. With an eye on the fertile lands of the rift valley populated by members of Moi's Kalenjin tribe, Kenyatta secured their support by first promoting Moi to Minister for Home Affairs in 1964, and then to vice-president in 1967. As a member of a minority tribe Moi was also an acceptable compromise for the major tribes. Moi was elected to the Kenyan parliament in 1963 from Baringo North. Since 1966 until his retirement in 2002 he served as the Baringo Central MP. However, Moi faced opposition from the Kikuyu elite known as the Kiambu Mafia,

who would have preferred one of their own to be eligible for the

presidency. This resulted in an infamous attempt by the constitutional

drafting group to change the constitution to prevent the vice-president

automatically assuming power in the event of the president's death. The

presence of this succession mechanism

may have led to dangerous political instability if Kenyatta died, given

his advanced age and perennial illnesses. However, Kenyatta withstood

the political pressure and safeguarded Moi's position. When

Jomo Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, Moi became president and took

the oath of office. He was popular, with widespread support all over

the country. He toured the country and came into contact with the

people everywhere, which was in great contrast to Kenyatta's imperial

style of governing behind closed doors. However, political realities

dictated that he would continue to be beholden to the Kenyatta system

which he had inherited intact, and he was still too weak to consolidate

his power. From the beginning, anticommunism was an important theme of

Moi's government; speaking on the new President's behalf, Vice-President Mwai Kibaki bluntly stated, "There is no room for communists in Kenya." On August 1, 1982, fate played into Moi's hands when forces loyal to his government defeated an attempted coup by Air Force officers led by Hezekiah Ochuka (1982 Kenyan coup d'état attempt).

To this day it appears that the attempt by two independent groups to

seize power contributed to the failure of both, with one group making

its attempt slightly earlier than the other. Moi

took the opportunity to dismiss political opponents and consolidate his

power. He reduced the influence of Kenyatta's men in the cabinet

through a long running judicial enquiry that resulted in the

identification of key Kenyatta men as traitors.

Moi pardoned them but not before establishing their traitor status in

the public view. The main conspirators in the coup, including Ochuka

were sentenced to death, marking the last judicial executions in Kenya.

He appointed supporters to key roles and changed the constitution to

establish a de jure single-party state. Kenya's

academics and other intelligentsia did not accept this and the

universities and colleges became the origin of movements that sought to

introduce democratic reforms. However, Kenyan secret police infiltrated these groups and many members moved into exile. Marxism could no longer be taught at Kenyan universities. Underground movements, e.g. Mwakenya and Pambana, were born. Moi's regime now faced the end of the Cold War, and an economy stagnating under rising oil prices and falling prices for agricultural commodities. At the same time the West no

longer dealt with Kenya as it had in the past, when it was viewed as a

strategic regional outpost against communist influences from Ethiopia

and Tanzania. At that time Kenya had received much foreign aid,

and the country was accepted as being well governed with Moi as a

legitimate leader and firmly in charge. The increasing amount of political repression, including the use of torture,

at the infamous Nyayo House torture chambers had been deliberately

overlooked. Some of the evidence of these torture cells were to be

later exposed in 2003 after Mwai Kibaki became President. However, a new thinking emerged after the end of the Cold War, and as Moi became increasingly viewed as a despot,

foreign aid was withheld pending compliance with economic and political

reforms. One of the key conditions imposed on his regime, especially by

the United States through fiery ambassador Smith Hempstone, was the restoration of a multi-party system.

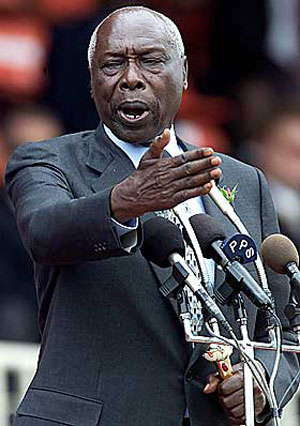

Moi managed to accomplish this against fierce opposition, single

handedly convincing the delegates at the KANU conference at Kasarani in

December, 1991. Moi won elections in 1992 and 1997, which were marred by political killings on

both sides. Moi skillfully exploited Kenya's mix of ethnic tensions in

these contests, with the ever present fear of the smaller tribes being

dominated by the larger tribes. In the absence of an effective and

organised opposition Moi had no difficulty in winning. Although it is

also suspected that electoral fraud may have occurred, the key to his victory in both elections was a divided opposition. In 1999 the findings of NGOs like Amnesty International and a special investigation by the United Nations were published which indicated that human rights abuses were prevalent in Kenya under the Moi regime. Reporting on corruption and human rights abuses by British reporter Mary Anne Fitzgerald from 1987 - 1988 resulted only in her being vilified by the government and finally deported. Moi was implicated in the 1990s Goldenberg scandal and subsequent cover-ups, where the Kenyan government subsidized exports of gold far in excess of the foreign currency earnings of exporters. In this case, the gold was smuggled from Congo,

as Kenya has negligible gold reserves. The Goldenberg scandal cost

Kenya the equivalent of more than 10% of the country's annual GDP. Half hearted

inquiries that began at the request of foreign aid donors came to

nothing during Moi's presidency. Although it appears that the peaceful

transfer of power to Mwai Kibaki may

have involved an understanding that Moi would not stand trial for

offences committed during his presidency, foreign aid donors reiterated

their requests and Kibaki reopened the inquiry. As the inquiry has

progressed, Moi, his two sons, Philip and Gideon (now a member of

Parliament), and his daughter June, as well as a host of high ranking

Kenyans, have been implicated. In bombshell testimony delivered in late

July 2003, Treasury Permanent Secretary Joseph Magari recounted that in 1991, Moi ordered him to pay Ksh34.5 million ($460,000) to Goldenberg, contrary to the laws then in force. In

October 2006, Moi was found, by the International Centre for Settlement

of Investment Disputes, to have taken a bribe from a Pakistani businessman to award monopoly of duty free shops at the country's

international airport in Mombasa and Nairobi. The businessman Ali Nasir

claimed to have paid Moi 2 million US$ in cash to obtain government

approval for the World Duty Free Limited investment in Kenya. On

31 August 2007, the Guardian published a secret report that laid bare a

web of shell companies, secret trusts and frontmen that his entourage

used to funnel hundreds of millions of pounds into nearly 30 countries. Moi

was constitutionally barred from running in the 2002 presidential

elections. Some of his supporters floated the idea of amending the

constitution to allow him to run for a third term, but Moi preferred to

retire, choosing Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Kenya's first President, as his successor. Mwai Kibaki,

was elected President by a two to one majority over Kenyatta, which was

confirmed on December 29, 2002. Kibaki was then wheelchair bound having

narrowly escaped death in a road traffic accident on the campaign trail. Moi

handed over power in a poorly organised ceremony that had one of the

largest crowds ever seen in Nairobi in attendance. The crowd was openly

hostile to Moi. After

leaving office in December 2002, Moi lived in retirement, largely

shunned by the political establishment. However, he still retained some

popularity with the masses, and his presence never failed to quickly

gather a crowd. He spoke out against a proposal for a new constitution

in 2005; according to Moi, the document was contrary to the aspirations

of the Kenyan people. After the proposal was defeated in a November 2005 constitutional referendum, Kibaki called Moi to arrange for a meeting to discuss the way forward. On July 25, 2007, Kibaki appointed Moi as special peace envoy to Sudan,

referring to Moi's "vast experience and knowledge of African affairs"

and "his stature as an elder statesman". In his capacity as peace

envoy, Moi's primary task was to help secure peace in southern Sudan,

where an agreement, signed in early 2005, was being implemented. At the

time, the Kenyan press speculated that Moi and Kibaki were planning an

alliance ahead of the December 2007 election. On

August 28, 2007, Moi announced his support for Kibaki's re-election and

said that he would campaign for Kibaki. He sharply criticized the two

opposition Orange Democratic Movement factions, arguing that they were tribal in nature. Moi owns the Kiptagich Tea Factory, which was established in 1979. In 2009 the factory was under threat of being closed down by the government during the Mau Forest evictions.

Daniel arap Moi married Lena Moi (born Helena Bommet) in 1950, but they separated in 1974, before his presidency. Thus "Mama Ngina",

the wife of Jomo Kenyatta, retained her first lady status. Lena died in

2004. Daniel arap Moi has eight children, five sons and three

daughters. Among the children are Gideon Moi (a former MP), Jonathan Toroitich (a former rally driver) and Philip Moi (a retired army officer). His older and only brother William Tuitoek died in 1995