<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Giovanni Domenico "Tommaso" Campanella, 1568

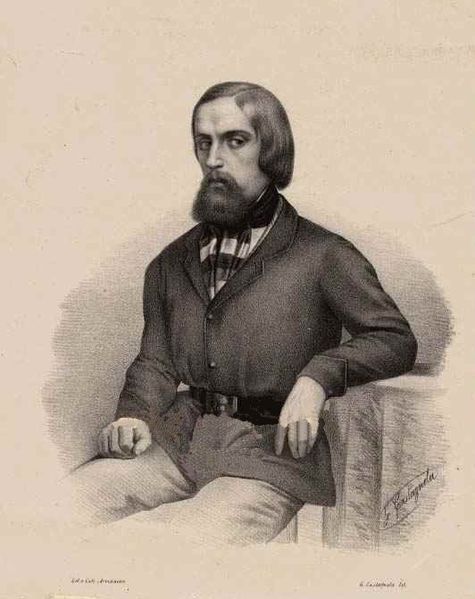

- Poet Goffredo Mameli, 1827

- 1st Lord of Sendai Date Masamune, 1567

PAGE SPONSOR

Goffredo Mameli (September 5, 1827 - July 6, 1849) was an Italian patriot, poet and writer, and a notable figure in the Italian Risorgimento. He is also the author of the lyrics of the current Italian national anthem.

The son of an aristocratic Sardinian admiral, Mameli was born in Genoa where his father was in command of the fleet of the kingdom of Sardinia. At the age of seven he was sent to Sardinia, to his grandfather's, to escape the risk of cholera, but soon came back to Genoa to complete his studies.

The achievements of Mameli's very short life are concentrated in only two years, during which time he played major parts in insurrectional movements and the Risorgimento. In 1847 Mameli joined the Società Entelema, a cultural movement that soon would have turned to a political movement, and here he became interested in the theories of Giuseppe Mazzini.

Mameli is mostly known as the author of the lyrics of the Italian national anthem, Il Canto degli Italiani (music by Michele Novaro). These lyrics were used for the first time in November 1847, celebrating King Charles Albert in his visit to Genoa after his first reforms. Mameli's lyrics to a "hymn of the people" — "Suona la tromba" — were set by Giuseppe Verdi the following year.

Mameli

was deeply involved in nationalist movements and some more

"spectacular" actions are remembered, such as his exposition of the Tricolore (current Italian flag, then prohibited) to celebrate the expulsion of Germans in 1846. Yet, he was with Nino Bixio (Garibaldi's

later major supporter and friend) in a committee for public health,

already on a clear Mazzinian position. In March 1848, hearing of the

insurrection in Milan,

Mameli organised an expedition with 300 other patriots, joined Bixio's

troops that were already on site, and entered the town. He was then

admitted to Garibaldi's irregular army (really the volunteer brigade of general Torres), as a captain, and met Mazzini.

Back in Genoa, he worked more on a literary side, wrote several hymns and other compositions, he became the director of the newspaper Diario del Popolo ("People's Daily"), and promoted a press campaign for a war against Austria. In December 1848 Mameli reached Rome, where Pellegrino Rossi had been murdered, helping in the clandestine works for declaration (February 9, 1849) of the Roman Republic. Mameli then went to Florence where he proposed the creation of a common state between Tuscany and Latium.

In April 1849 he was again in Genoa, with Bixio, where a popular insurrection was strongly opposed by General Alberto La Marmora. Mameli soon left again for Rome, where the French had come to support the Papacy (Pope Pius IX had actually escaped from the town) and took active part in the combat. In June, Mameli was accidentally injured in his left leg by the bayonet of

one of his comrades. The wound was not serious, but an infection took

hold, and after a time the leg had to be amputated. Mameli died of the

infection on July 6, about two months before his 22nd birthday.

Il Canto degli Italiani (The Song of the Italians) is the Italian national anthem. It is best known among Italians as L'Inno di Mameli (Mameli's Hymn) and often referred to as Fratelli d'Italia (Brothers of Italy), from its opening line. The words were written in the autumn of 1847 in Genoa, by the then 20 year old student and patriot Goffredo Mameli, in a climate of popular struggle for unification and independence of Italy which foreshadowed the war against Austria. Two months later, they were set to music in Turin by another Genoese, Michele Novaro. The hymn enjoyed widespread popularity throughout the period of the Risorgimento and in the following decades.

After unification (1861) the adopted national anthem was the Marcia Reale, the Royal March (or Fanfara Reale), official hymn of the royal house of Savoy composed in 1831 to order of Carlo Alberto di Savoia. The Marcia Reale remained the Italian national anthem until Italy became a republic in 1946. Giuseppe Verdi, in his Inno delle Nazioni (Hymn of the Nations), composed for the London International Exhibition of 1862, chose Il Canto degli Italiani – and not the Marcia Reale – to represent Italy, putting it beside God Save the Queen and the Marseillaise.

In 1946 Italy became a republic, and on October 12, 1946, Il Canto degli Italiani was

provisionally chosen as the country's new national anthem. This choice

was made official in law only on November 17, 2005, almost 60 years

later. The first manuscript of the poem, preserved at the Istituto Mazziniano in

Genoa, appears in a personal copybook of the poet, where he collected

notes, thoughts and other writings. Of uncertain dating, the manuscript

reveals anxiety and inspiration at the same time. The poet begins with È sorta dal feretro (It's risen from the bier)

then seems to change his mind: leaves some room, begins a new paragraph

and writes "Evviva l'Italia, l'Italia s'è desta" (Hurray Italy, Italy has awakened).

Handwriting appears nervy and frenetic, with the numerous spelling

errors, among which "Ilia" for "Italia" and "Ballilla" for "Balilla".

The last strophe is deleted by the author, to the point of being barely

readable. It was dedicated to Italian women:

The second manuscript is the copy that Mameli sent to Novaro for setting it to music. It shows a much steadier handwriting, fixes misspellings and has a significant modification: the incipit is "Fratelli d'Italia". This copy is in Museo del Risorgimento in Turin. The hymn was also printed on leaflets in Genoa, by the printing office Casamara. The Istituto Mazziniano has a copy of these, with hand annotations by Mameli himself. This sheet, subsequent to the two manuscripts, lacks the last strophe ("Son giunchi che piegano...") for fear of censorship. These leaflets were to be distributed on the December 10 demonstration, in Genoa.

December 10, 1847 was a historical day for Italy: the demonstration was

officially dedicated to the 101st anniversary of the popular rebellion

which led to the expulsion of the Austrian powers from the city; in

fact it was an excuse to protest against foreign occupations in Italy

and induce Carlo Alberto to embrace the Italian cause of liberty. In

this occasion the tricolor flag was shown and the Mameli's hymn was

publicly sung for the first time. After

December 10 the hymn spread all over the Italian peninsula, brought by

the same patriots that participated in the Genoa demonstration.

This is the complete text of the original poem written by Goffredo Mameli; however the Italian anthem, as performed in every official occasion, is composed of the first stanza, sung twice, and the chorus, then ends with a loud "Sì!" ("Yes!"). The third stanza is an invocation to God to protect the loving union of the Italians struggling to form their unified nation once and for all, the fourth recalls popular heroic figures and moments of Italian independence such as the Vespri siciliani, the riot started in Genoa by Balilla and the battle of Legnano. The last stanza of the poem refers to the part played by Habsburg Austria and Czarist Russia in the partitions of Poland, linking its quest for independence to the Italian one.

|

|