<Back to Index>

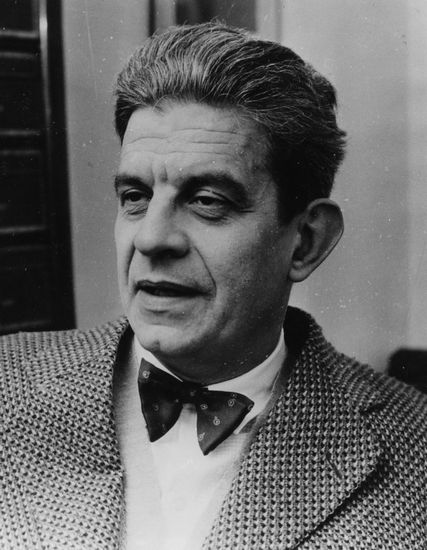

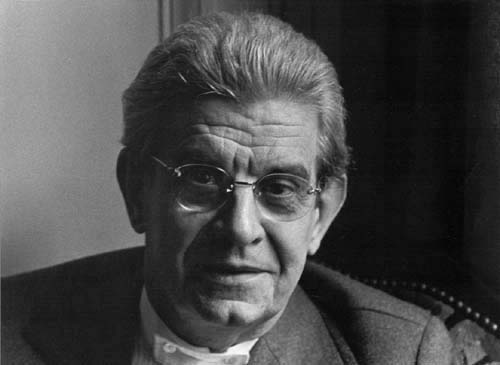

- Psychoanalyst and Psychiatrist Jacques Marie Émile Lacan, 1901

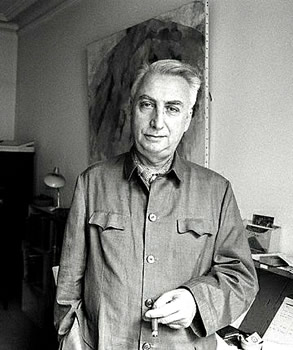

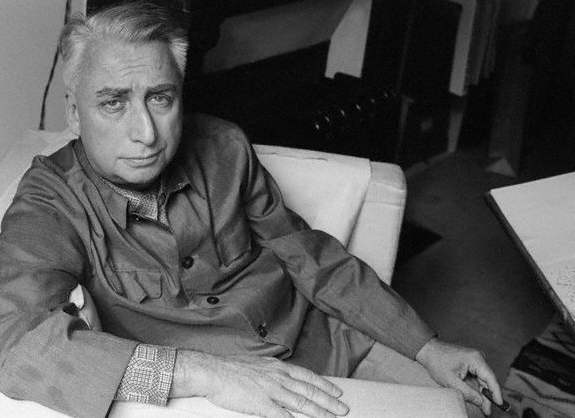

- Philosopher and Literary Theorist Roland Gérard Barthes, 1915

PAGE SPONSOR

Jacques Marie Émile Lacan (April 13, 1901 – September 9, 1981) was a French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist who made prominent contributions to psychoanalysis and philosophy, and has been called "the most controversial psycho - analyst since Freud". Lacan's post - structuralist theory rejected the belief that reality can be captured in language. Giving yearly seminars in Paris from 1953 to 1981, Lacan influenced France's intellectuals in the 1960s and the 1970s, especially the post - structuralist philosophers. His interdisciplinary work was as a "self - proclaimed Freudian.... 'It is up to you to be Lacanians if you wish. I am a Freudian'"; and featured the unconscious, the castration complex, the ego, identification, and language as subjective perception. His ideas have had a significant impact on critical theory, literary theory, 20th century French philosophy, sociology, feminist theory, film theory and clinical psychoanalysis.

Lacan was born in Paris, the eldest of Emilie and Alfred Lacan's three children. His father was a successful soap and oils salesman. His mother was ardently Catholic — his younger brother went to a monastery in 1929 and Lacan attended the Jesuit Collège Stanislas. During the early 1920s, Lacan attended right wing Action Française political meetings and met the founder, Charles Maurras. By the mid 1920s, Lacan had become dissatisfied with religion and quarreled with his family over it.

In 1920, on being rejected as too thin for military service, he entered medical school and, in 1926, specialized in psychiatry at the Sainte - Anne Hospital in Paris. He was especially interested in the philosophies of Karl Jaspers and Martin Heidegger and attended the seminars about Hegel given by Alexandre Kojève. Sometime in that decade, and until 1938, Lacan sought psychoanalysis by Rudolph Loewenstein. The analysis was lengthy and perhaps not wholly successful: "Loewenstein... often expressed his opinion orally to the people around him: the man was unanalyzable. And Lacan was unanalyzable in those conditions".

In 1931, Lacan became a licensed forensic psychiatrist. In 1932, he was awarded the Doctorat d'état for his thesis On Paranoiac Psychosis in its Relations to the Personality (De la Psychose paranoïaque dans ses rapports avec la personnalité suivi de Premiers écrits sur la paranoïa. Paris : Éditions du Seuil, 1975). Psychoanalysts mostly ignored it, although it was acclaimed beyond psychoanalytic circles, especially by surrealist artists. Two years later, he was elected to the Société psychanalytique de Paris. In January 1934, he married Marie - Louise Blondin and they had their first child, a daughter called Caroline. Their second child, a son named Thibaut, was born in August 1939.

In 1936, Lacan presented his first analytic report at the Congress of the International Psychoanalytical Association in Marienbad on the "Mirror Phase". The congress chairman, Ernest Jones, terminated the lecture before its conclusion, since he was unwilling to extend Lacan's stated presentation time. Insulted, Lacan left the congress to witness the Berlin Olympic Games. Unfortunately, no copy of the original lecture remains.

Lacan was an active intellectual of the inter war period — he associated with André Breton, Georges Bataille, Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso. He attended the mouvement Psyché that Maryse Choisy founded. He published in the Surrealist journal Minotaure and attended the first public reading of James Joyce's Ulysses. "[Lacan's] interest in surrealism predated his interest in psychoanalysis," Dylan Evans explains, speculating that "perhaps Lacan never really abandoned his early surrealist sympathies, its neo - Romantic view of madness as ‘convulsive beauty’, its celebration of irrationality, and its hostility to the scientist who murders nature by dissecting it". Others would agree that "the importance of surrealism can hardly be overstated... to the young Lacan... [who] also shared the surrealists' taste for scandal and provocation, and viewed provocation as an important element in psycho - analysis itself".

The Société Psychoanalytique de Paris (SPP) was disbanded due to Nazi Germany's occupation of France in 1940. Lacan was called up to serve in the French army at the Val - de - Grâce military hospital in Paris, where he spent the duration of the war. His third child, Sibylle, was born in 1940.

The following year, Lacan fathered a child, Judith (who kept the name Bataille), with Sylvia Bataille (née Maklès), the estranged wife of his friend Georges Bataille. There are contradictory accounts of his romantic life with Sylvia in southern France during the war. The official record shows only that Marie - Louise requested divorce after Judith's birth and that Lacan married Sylvia in 1953.

After the war, the SPP recommenced their meetings. Lacan visited England for a five week study trip, where he met the English analysts Wilfred Bion and John Rickman. Bion’s analytic work with groups influenced Lacan, contributing to his own subsequent emphasis on study groups as a structure within which to advance theoretical work in psychoanalysis. In 1949, Lacan presented a new paper on the mirror stage to the sixteenth IPA congress in Zurich.

In 1951, Lacan started to hold a private weekly seminar in Paris, in which he urged what he described as "a return to Freud" that would concentrate on the linguistic nature of psychological symptomatology. Becoming public in 1953, Lacan's twenty - seven year long seminar was highly influential in Parisian cultural life, as well as in psychoanalytic theory and clinical practice.

In 1953, after a disagreement over the variable length session, Lacan and many of his colleagues left the Société Parisienne de Psychanalyse to form a new group, the Société Française de Psychanalyse (SFP). One consequence of this was to deprive the new group of membership within the International Psychoanalytical Association.

Encouraged by the reception of "the return to Freud" and of his report "The Function and Field of Speech and Language in Psychoanalysis," Lacan began to re-read Freud's works in relation to contemporary philosophy, linguistics, ethnology, biology and topology. From 1953 to 1964 at the Sainte - Anne Hospital, he held his Seminars and presented case histories of patients. During this period he wrote the texts that are found in the collection Écrits, which was first published in 1966. In his seventh Seminar "The Ethics of Psychoanalysis" (1959 – 60), Lacan defined the ethical foundations of psychoanalysis and presented his "ethics for our time" — one that would, in the words of Freud, prove to be equal to the tragedy of modern man and to the "discontent of civilization." At the roots of the ethics is desire: analysis' only promise is austere, it is the entrance - into - the - I (in French a play on words between l'entrée en je and l'entrée en jeu). "I must come to the place where the id was," where the analysand discovers, in its absolute nakedness, the truth of his desire. The end of psychoanalysis entails "the purification of desire." This text formed the foundation of Lacan's work for the subsequent years. He defended three assertions: that psychoanalysis must have a scientific status; that Freudian ideas have radically changed the concepts of subject, of knowledge, and of desire; and that the analytic field is the only place from which it is possible to question the insufficiencies of science and philosophy.

Starting in 1962, a complex negotiation took place to determine the status of the SFP within the IPA. Lacan’s practice (with its controversial indeterminate length sessions) and his critical stance towards psychoanalytic orthodoxy led, in 1963, to the IPA setting the condition that registration of the SFP was dependent upon the removal of Lacan from the list of SFP analysts. Lacan left the SFP to form his own school, which became known as the École Freudienne de Paris (EFP), and "took many representatives of the third generation with him: among them were Maud and Octave Mannoni, Serge Leclaire... and Jean Clavreul".

With Lévi - Strauss and Althusser's support, Lacan was appointed lecturer at the École Pratique des Hautes Etudes. He started with a seminar on The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis in January 1964 in the Dussane room at the École Normale Supérieure. Lacan began to set forth his own approach to psychoanalysis to an audience of colleagues that had joined him from the SFP. His lectures also attracted many of the École Normale’s students. He divided the École de la Cause freudienne into three sections: the section of pure psychoanalysis (training and elaboration of the theory, where members who have been analyzed but haven't become analysts can participate); the section for applied psychoanalysis (therapeutic and clinical, physicians who either have not started or have not yet completed analysis are welcome); and the section for taking inventory of the Freudian field (concerning the critique of psychoanalytic literature and the analysis of the theoretical relations with related or affiliated sciences).

By the 1960s, Lacan was associated, at least in the public mind, with the far left in France. In May 1968, Lacan voiced his sympathy for the student protests and as a corollary his followers set up a Department of Psychology at the University of Vincennes (Paris VIII). In 1969, Lacan moved his public seminars to the Faculté de Droit (Panthéon), where he continued to deliver his expositions of analytic theory and practice until the dissolution of his School in 1980.

Throughout the final decade of his life, Lacan continued his widely followed seminars. During this period, he developed his concepts of masculine and feminine jouissance and placed an increased emphasis on the concept of "the Real" as a point of impossible contradiction in the "Symbolic order". This late work had the greatest influence on feminist thought, as well as upon the informal movement that arose in the 1970s or 1980s called post - modernism.

Lacan's "return to Freud" emphasizes a renewed attention to the original texts of Freud, and included a radical critique of Ego psychology, whereas "Lacan's quarrel with Object Relations psychoanalysis" was a more muted affair. Here he attempted "to restore to the notion of the Object Relation... the capital of experience that legitimately belongs to it", building upon what he termed "the hesitant, but controlled work of Melanie Klein... Through her we know the function of the imaginary primordial enclosure formed by the imago of the mother's body", as well as upon "the notion of the transitional object, introduced by D.W. Winnicott... a key point for the explanation of the genesis of fetishism". Nevertheless, "Lacan systematically questioned those psychoanalytic developments from the 1930s to the 1970s, which were increasingly and almost exclusively focused on the child's early relations with the mother... the pre - Oedipal or Kleinian mother"; and Lacan's rereading of Freud — "characteristically, Lacan insists that his return to Freud supplies the only valid model" — formed a basic conceptual starting point in that oppositional strategy.

Lacan thought that Freud's ideas of "slips of the tongue," jokes, and the interpretation of dreams all emphasized the agency of language in subjective constitution. In "The Agency of the Letter in the Unconscious, or Reason Since Freud," he proposes that "the unconscious is structured like a language." The unconscious is not a primitive or archetypal part of the mind separate from the conscious, linguistic ego, he explained, but rather a formation as complex and structurally sophisticated as consciousness itself. One consequence of the unconscious being structured like a language is that the self is denied any point of reference to which to be "restored" following trauma or a crisis of identity.

Andre Green objected that "when you read Freud, it is obvious that this proposition doesn't work for a minute. Freud very clearly opposes the unconscious (which he says is constituted by thing - presentations and nothing else) to the pre - conscious. What is related to language can only belong to the pre - conscious". Freud certainly contrasted "the presentation of the word and the presentation of the thing... the unconscious presentation is the presentation of the thing alone" in his metapsychology. However "Dylan Evans, Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis... takes issue with those who, like Andre Green, question the linguistic aspect of the unconscious, emphasizing Lacan's distinction between das Ding and die Sache in Freud's account of thing - presentation". Green's criticism of Lacan also included accusations of intellectual dishonesty, he said, "“ [He] cheated everybody… the return to Freud was an excuse, it just meant going to Lacan."

Lacan's first official contribution to psychoanalysis was the mirror stage, which he described as "formative of the function of the I as revealed in psychoanalytic experience." By the early 1950s, he came to regard the mirror stage as more than a moment in the life of the infant; instead, it formed part of the permanent structure of subjectivity. In "the Imaginary order," their own image permanently catches and captivates the subject. Lacan explains that "the mirror stage is a phenomenon to which I assign a twofold value. In the first place, it has historical value as it marks a decisive turning point in the mental development of the child. In the second place, it typifies an essential libidinal relationship with the body image".

As this concept developed further, the stress fell less on its historical value and more on its structural value. In his fourth Seminar, "La relation d'objet," Lacan states that "the mirror stage is far from a mere phenomenon which occurs in the development of the child. It illustrates the conflictual nature of the dual relationship."

The mirror stage describes the formation of the Ego via the process of objectification, the Ego being the result of a conflict between one's perceived visual appearance and one's emotional experience. This identification is what Lacan called alienation. At six months, the baby still lacks physical co-ordination. The child is able to recognize themselves in a mirror prior to the attainment of control over their bodily movements. The child sees their image as a whole and the synthesis of this image produces a sense of contrast with the lack of co-ordination of the body, which is perceived as a fragmented body. The child experiences this contrast initially as a rivalry with their image, because the wholeness of the image threatens the child with fragmentation — thus the mirror stage gives rise to an aggressive tension between the subject and the image. To resolve this aggressive tension, the child identifies with the image: this primary identification with the counterpart forms the Ego. Lacan understands this moment of identification as a moment of jubilation, since it leads to an imaginary sense of mastery; yet when the child compares their own precarious sense of mastery with the omnipotence of the mother, a depressive reaction may accompany the jubilation.

Lacan calls the specular image "orthopaedic," since it leads the child to anticipate the overcoming of its "real specific prematurity of birth." The vision of the body as integrated and contained, in opposition to the child's actual experience of motor incapacity and the sense of his or her body as fragmented, induces a movement from "insufficiency to anticipation." In other words, the mirror image initiates and then aids, like a crutch, the process of the formation of an integrated sense of self.

In the mirror stage a "misunderstanding" (méconnaissance) constitutes the Ego — the "me" (moi) becomes alienated from itself through the introduction of an imaginary dimension to the subject. The mirror stage also has a significant symbolic dimension, due to the presence of the figure of the adult who carries the infant. Having jubilantly assumed the image as their own, the child turns their head towards this adult, who represents the big Other, as if to call on the adult to ratify this image.

While Freud uses the term "other", referring to der Andere (the other person) and "das Andere" (otherness), under the influence of Alexandre Kojève, Lacan's use is closer to Hegel's.

Lacan often used an algebraic symbology for his concepts: the big Other is designated A (for French Autre) and the little other is designated a (italicized French autre). He asserts that an awareness of this distinction is fundamental to analytic practice: "the analyst must be imbued with the difference between A and a, so he can situate himself in the place of Other, and not the other." Dylan Evans explains that:

"1. The little other is the other who is not really other, but a reflection and projection of the Ego. He [autre] is simultaneously the counterpart and the specular image. The little other is thus entirely inscribed in the imaginary order.

2. The big Other designates radical alterity, an other-ness which transcends the illusory otherness of the imaginary because it cannot be assimilated through identification. Lacan equates this radical alterity with language and the law, and hence the big Other is inscribed in the order of the symbolic. Indeed, the big Other is the symbolic insofar as it is particularized for each subject. The Other is thus both another subject, in his radical alterity and unassimilable uniqueness, and also the symbolic order which mediates the relationship with that other subject."

"The Other must first of all be considered a locus," Lacan writes, "the locus in which speech is constituted". We can speak of the Other as a subject in a secondary sense only when a subject occupies this position and thereby embodies the Other for another subject.

In arguing that speech originates not in the Ego nor in the subject but rather in the Other, Lacan stresses that speech and language are beyond the subject's conscious control. They come from another place, outside of consciousness — "the unconscious is the discourse of the Other." When conceiving the Other as a place, Lacan refers to Freud's concept of psychical locality, in which the unconscious is described as "the other scene".

"It is the mother who first occupies the position of the big Other for the child," Dylan Evans explains, "it is she who receives the child's primitive cries and retroactively sanctions them as a particular message". The castration complex is formed when the child discovers that this Other is not complete because there is a "Lack (manque)" in the Other. This means that there is always a signifier missing from the trove of signifiers constituted by the Other. Lacan illustrates this incomplete Other graphically by striking a bar through the symbol A; hence another name for the castrated, incomplete Other is the "barred Other."

Feminist thinkers have both utilized and criticized Lacan's concepts of castration and the Phallus. Some feminists have argued that Lacan's phallocentric analysis provides a useful means of understanding gender biases and imposed roles, while other feminist critics, most notably Luce Irigaray, accuse Lacan of maintaining the sexist tradition in psychoanalysis. For Irigaray, the Phallus does not define a single axis of gender by its presence / absence; instead, gender has two positive poles. Like Irigaray, Jacques Derrida, in criticizing Lacan's concept of castration, discusses the phallus in a chiasmus with the hymen, as both one and other. Other feminists, such as Judith Butler, Jane Gallop and Elizabeth Grosz, have interpreted Lacan's work as opening up new possibilities for feminist theory.

The Imaginary is the field of images and imagination, and deception. The main illusions of this order are synthesis, autonomy, duality and similarity. Lacan thought that the relationship created within the mirror stage between the Ego and the reflected image means that the Ego and the Imaginary order itself are places of radical alienation: "alienation is constitutive of the Imaginary order." This relationship is also narcissistic.

In The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Lacan argues that the Symbolic order structures the visual field of the Imaginary, which means that it involves a linguistic dimension. If the signifier is the foundation of the Symbolic, the signified and signification are part of the Imaginary order. Language has Symbolic and Imaginary connotations — in its Imaginary aspect, language is the "wall of language" that inverts and distorts the discourse of the Other. On the other hand, the Imaginary is rooted in the subject's relationship with his or her own body (the image of the body). In Fetishism: the Symbolic, the Imaginary and the Real, Lacan argues that in the sexual plane the Imaginary appears as sexual display and courtship love.

Insofar as identification with the analyst is the objective of analysis, Lacan accused major psychoanalytic schools of reducing the practice of psychoanalysis to the Imaginary order. Instead, Lacan proposes the use of the Symbolic to dislodge the disabling fixations of the Imaginary — the analyst transforms the images into words. "The use of the Symbolic," he argued, "is the only way for the analytic process to cross the plane of identification."

In his Seminar IV, "La relation d'objet," Lacan argues that the concepts of "Law" and "Structure" are unthinkable without language — thus the Symbolic is a linguistic dimension. This order is not equivalent to language, however, since language involves the Imaginary and the Real as well. The dimension proper to language in the Symbolic is that of the signifier — that is, a dimension in which elements have no positive existence, but which are constituted by virtue of their mutual differences.

The Symbolic is also the field of radical alterity — that is, the Other; the unconscious is the discourse of this Other. It is the realm of the Law that regulates desire in the Oedipus complex. The Symbolic is the domain of culture as opposed to the Imaginary order of nature. As important elements in the Symbolic, the concepts of death and lack (manque) connive to make of the pleasure principle the regulator of the distance from the Thing ("das Ding an sich") and the death drive that goes "beyond the pleasure principle by means of repetition" — "the death drive is only a mask of the Symbolic order."

By working in the Symbolic order, the analyst is able to produce changes in the subjective position of the analysand. These changes will produce imaginary effects because the Imaginary is structured by the Symbolic.

Lacan's concept of the Real dates back to 1936 and his doctoral thesis on psychosis. It was a term that was popular at the time, particularly with Émile Meyerson, who referred to it as "an ontological absolute, a true being - in - itself". Lacan returned to the theme of the Real in 1953 and continued to develop it until his death. The Real, for Lacan, is not synonymous with reality. Not only opposed to the Imaginary, the Real is also exterior to the Symbolic. Unlike the latter, which is constituted in terms of oppositions (i.e. presence / absence), "there is no absence in the Real." Whereas the Symbolic opposition "presence / absence" implies the possibility that something may be missing from the Symbolic, "the Real is always in its place." If the Symbolic is a set of differentiated elements (signifiers), the Real in itself is undifferentiated — it bears no fissure. The Symbolic introduces "a cut in the real" in the process of signification: "it is the world of words that creates the world of things — things originally confused in the "here and now" of the all in the process of coming into being." The Real is that which is outside language and that resists symbolization absolutely. In Seminar XI Lacan defines the Real as "the impossible" because it is impossible to imagine, impossible to integrate into the Symbolic, and impossible to attain. It is this resistance to symbolization that lends the Real its traumatic quality. Finally, the Real is the object of anxiety, insofar as it lacks any possible mediation and is "the essential object which is not an object any longer, but this something faced with which all words cease and all categories fail, the object of anxiety par excellence."

Lacan's conception of desire is central to his theories and follows Freud's concept of Wunsch. The aim of psychoanalysis is to lead the analysand and to uncover the truth about his or her desire, but this is possible only if that desire is articulated. Lacan wrote that "it is only once it is formulated, named in the presence of the other, that desire appears in the full sense of the term." This naming of desire "is not a question of recognizing something which would be entirely given. In naming it, the subject creates, brings forth, a new presence in the world." Psychoanalysis teaches the patient "to bring desire into existence." The truth about desire is somehow present in discourse, although discourse is never able to articulate the entire truth about desire — whenever discourse attempts to articulate desire, there is always a leftover or surplus.

In "The Signification of the Phallus," Lacan distinguishes desire from need and demand. Need is a biological instinct that is articulated in demand, yet demand has a double function: on the one hand, it articulates need, and on the other, acts as a demand for love. Even after the need articulated in demand is satisfied, the demand for love remains unsatisfied. This remainder is desire. For Lacan, "desire is neither the appetite for satisfaction nor the demand for love, but the difference that results from the subtraction of the first from the second." Lacan adds that "desire begins to take shape in the margin in which demand becomes separated from need." Hence desire can never be satisfied, or as Slavoj Žižek puts it, "desire's raison d'être is not to realize its goal, to find full satisfaction, but to reproduce itself as desire."

It is also important to distinguish between desire and the drives. The drives are the partial manifestations of a single force called desire. Lacan's concept of the "objet petit a" is the object of desire, although this object is not that towards which desire tends, but rather the cause of desire. Desire is not a relation to an object but a relation to a lack (manque).

Lacan maintains Freud's distinction between drive (Trieb) and instinct (Instinkt). Drives differ from biological needs because they can never be satisfied and do not aim at an object but rather circle perpetually around it. The true source of jouissance is the repetition of the movement of this closed circuit. Lacan posits the drives as both cultural and symbolic constructs — to him, "the drive is not a given, something archaic, primordial." He incorporates the four elements of the drives as defined by Freud (the pressure, the end, the object and the source) to his theory of the drive's circuit: the drive originates in the erogenous zone, circles round the object, and returns to the erogenous zone. The three grammatical voices structure this circuit:

- the active voice (to see)

- the reflexive voice (to see oneself)

- the passive voice (to be seen)

The active and reflexive voices are autoerotic — they lack a subject. It is only when the drive completes its circuit with the passive voice that a new subject appears. Despite being the "passive" voice, the drive is essentially active: "to make oneself be seen" rather than "to be seen." The circuit of the drive is the only way for the subject to transgress the pleasure principle.

Lacan identifies four partial drives: the oral drive (the erogenous zones are the lips, the partial object the breast), the anal drive (the anus and the faeces), the scopic drive (the eyes and the gaze) and the invocatory drive (the ears and the voice). The first two relate to demand and the last two to desire. If the drives are closely related to desire, they are the partial aspects in which desire is realized — desire is one and undivided, whereas the drives are its partial manifestations.

Building on Freud's The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Lacan long argued that "every unsuccessful act is a successful, not to say 'well - turned', discourse", highlighting as well "sudden transformations of errors into truths, which seemed to be due to nothing more than perseverance". In a late seminar, he generalized more fully the psychoanalytic discovery of "truth — arising from misunderstanding", so as to maintain that "the subject is naturally erring... discourse structures alone give him his moorings and reference points, signs identify and orient him; if he neglects, forgets, or loses them, he is condemned to err anew".

Because of "the alienation to which speaking beings are subjected due to their being in language", to survive "one must let oneself be taken in by signs and become the dupe of a discourse... [of] fictions organized in to a discourse". For Lacan, with "masculine knowledge irredeemably an erring", the individual "must thus allow himself to be fooled by these signs to have a chance of getting his bearings amidst them; he must place and maintain himself in the wake of a discourse... become the dupe of a discourse... les Non-dupes errent".

Lacan comes close here to one of the points where "very occasionally he sounds like Thomas Kuhn (whom he never mentions)", with Lacan's "discourse" resembling Kuhn's "paradigm" seen as "the entire constellation of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by the members of a given community" – something reinforced perhaps by Kuhn's approval of "Francis Bacon's acute methodological dictum: 'Truth emerges more readily from error than from confusion'".

The "variable - length psychoanalytic session" was one of Lacan's crucial clinical innovations, and a key element in his conflicts with the IPA, to whom his "innovation of reducing the fifty minute analytic hour to a Delphic seven or eight minutes (or sometimes even to a single oracular parole murmured in the waiting room)" was unacceptable. Lacan's variable length sessions lasted anywhere from a few minutes (or even, if deemed appropriate by the analyst, a few seconds) to several hours. This practice replaced the classical Freudian "fifty minute hour".

With respect to what he called "the cutting up of the 'timing'", Lacan asked the question, "Why make an intervention impossible at this point, which is consequently privileged in this way?" By allowing the analyst's intervention on timing, the variable length session removed the patient's — or, technically, "the analysand's" — former certainty as to the length of time that they would be on the couch. When Lacan adopted the practice, "the psychoanalytic establishment were scandalized" — and, given that "between 1979 and 1980 he saw an average of ten patients an hour", it is perhaps not hard to see why: "psychoanalysis reduced to zero", if no less lucrative.

At the time of his original innovation, Lacan described the issue as concerning "the systematic use of shorter sessions in certain analyses, and in particular in training analyses"; and in practice it was certainly a shortening of the session around the so-called "critical moment" which took place, so that critics wrote that 'everyone is well aware what is meant by the deceptive phrase "variable length"... sessions systematically reduced to just a few minutes'. Irrespective of the theoretical merits of breaking up patients' expectations, it was clear that "the Lacanian analyst never wants to 'shake up' the routine by keeping them for more rather than less time".

"Whatever the justification, the practical effects were startling. It does not take a cynic to point out that Lacan was able to take on many more analysands than anyone using classical Freudian techniques... [and] as the technique was adopted by his pupils and followers an almost exponential rate of growth became possible".

Accepting the importance of "the critical moment when insight arises", object relations theory would nonetheless quietly suggest that "if the analyst does not provide the patient with space in which nothing needs to happen there is no space in which something can happen". Julia Kristeva, if in very different language, would concur that "Lacan, alert to the scandal of the timeless intrinsic to the analytic experience, was mistaken in wanting to ritualize it as a technique of scansion (short sessions)".

Jacques - Alain Miller is the sole editor of Lacan's seminars, which contain the majority of his life's work. "There has been considerable controversy over the accuracy or otherwise of the transcription and editing", as well as over "Miller's refusal to allow any critical or annotated edition to be published". Despite Lacan's status as a major figure in the history of psychoanalysis, some of his seminars remain unpublished. Since 1984, Miller had been regularly conducting a series of lectures, "L'orientation lacanienne." Miller's teachings have been published in the U.S. by the journal Lacanian Ink.

Lacan claimed that his Écrits were not to be understood rationally, but would rather produce an effect in the reader similar to the sense of enlightenment one might experience while reading mystical texts. Lacan's writing is notoriously difficult, due in part to the repeated Hegelian / Kojèvean allusions, wide theoretical divergences from other psychoanalytic and philosophical theory, and an obscure prose style. For some, "the impenetrability of Lacan's prose... [is] too often regarded as profundity precisely because it cannot be understood". Arguably at least, "the imitation of his style by other 'Lacanian' commentators" has resulted in "an obscurantist antisystematic tradition in Lacanian literature".

The broader psychotherapeutic literature has little or nothing to say about the effectiveness of Lacanian psychoanalysis. Though a major influence on psychoanalysis in France and parts of Latin America, Lacan's influence on clinical psychology in the English speaking world is negligible, where his ideas are best known in the arts and humanities.

A notable exception is the works of Dr. Annie G. Rogers (A Shining Affliction; The Unsayable: The Hidden Language of Trauma), which credit Lacanian theory for many therapeutic insights in successfully treating sexually abused young women.

Alan D. Sokal and Jean Bricmont in their book Fashionable Nonsense have criticized Lacan's use of terms from mathematical fields such as topology, accusing him of "superficial erudition" and of abusing scientific concepts that he does not understand. Other critics have dismissed Lacan's work wholesale. François Roustang called it an "incoherent system of pseudo - scientific gibberish," and quoted linguist Noam Chomsky's opinion that Lacan was an "amusing and perfectly self - conscious charlatan". Dylan Evans, formerly a Lacanian analyst, eventually dismissed Lacanianism as lacking a sound scientific basis and for harming rather than helping patients, and has criticized Lacan's followers for treating his writings as "holy writ." Richard Webster has decried what he sees as Lacan's obscurity, arrogance, and the resultant "Cult of Lacan". Richard Dawkins, in a review of Fashionable Nonsense, said regarding Lacan: "We do not need the mathematical expertise of Sokal and Bricmont to assure us that the author of this stuff is a fake. Perhaps he is genuine when he speaks of non - scientific subjects? But a philosopher who is caught equating the erectile organ to the square root of minus one has, for my money, blown his credentials when it comes to things that I don't know anything about."

Lacan's colleague Daniel Lagache considered that "[Lacan] embodied the analyst's bad conscience. But... a good conscience in a psychoanalyst is no less dangerous". Others have been more forceful, describing him as "The Shrink from Hell... [an] attractive psychopath", and detailing a long list of collateral damage to "patients, colleagues, mistresses, wives, children, publishers, editors and opponents... [as his] lunatic legacy". Certainly many of "the conflicts around Lacan's school and his person" have been linked to the "form of charismatic authority which, in his personal and institutional presence, he so dramatically provoked". Lacan himself defended his approach on the grounds that "psychosis is an attempt at rigor... I am psychotic for the simple reason that I have always tried to be rigorous".

Malcolm Bowie has suggested that Lacan "had the fatal weakness of all those who are fanatically against all forms of totalization (the complete picture) in the so-called human sciences: a love of system". Similarly, Jacqueline Rose has argued that "Lacan was implicated in the phallocentrism he described, just as his utterance constantly rejoins the mastery which he sought to undermine". Feminists would then raise the question: "is Lacan, in claiming the law of the father, merely himself in the grip of the Oedipus complex?"

While it is widely recognized that "Lacan was... an intellectual magpie", this was not simply a matter of borrowing from others. Instead, "Lacan was so zealous in invoking other men's work and claiming to base his own arguments on them, when in reality he was departing from their teachings, leaving behind mere skeletons". Even with Freud, it is seldom clearly signposted when Lacan is expounding Freud, when he is reinterpreting Freud, or when he is proposing a completely new theory in Freudian guise. The result was "a complete pattern of dissenting assent to the ideas of Freud... Lacan's argument is conducted on Freud's behalf and, at the same time, against him", so as to leave Lacan himself the "master" of his (and everyone's) thought. "Castoriadis... maintained that Lacan had gradually come to prevent anyone else from thinking because of the way he tried to make all thought dependent on himself".

More personal criticism of his intellectual style is that it depended on a kind of teasing lure — "fundamental truths to be revealed... but always at some further point". In such a (feminist) perspective, "Lacan's sadistic capriciousness reveals the prick behind the Phallus... a narcissistic tease who persuades by means of attraction and resistance, not by orderly systematic discourse". To intimates like Dolto, "Lacan was like a narcissistic and wayward child... All he thought about was himself and his work". Yet if Lacan was a narcissist, if his writings are essentially "the confessions of a self - justifying megalomaniac", fueled by "Lacan's craving for recognition — his almost demonic hunger" — if they reveal "a narcissistic enjoyment of mystification as a form of omnipotent power... fantasies of narcissistic omnipotence", yet Lacan was clearly one of "what Maccoby calls 'productive narcissists'... [who] get others to buy into their vision and help to make it a reality... the narcissists who change our world".

Roland Gérard Barthes (12 November 1915 – 25 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, philosopher, critic and semiotician. Barthes' ideas explored a diverse range of fields and he influenced the development of schools of theory including structuralism, semiotics, social theory, anthropology and post - structuralism.

Roland Barthes was born on 12 November 1915 in the town of Cherbourg in Normandy. He was the son of naval officer Louis Barthes, who was killed in a battle in the North Sea before his son was one year old. His mother, Henriette Barthes, and his aunt and grandmother raised him in the village of Urt and the city of Bayonne. When Barthes was eleven, his family moved to Paris, though his attachment to his provincial roots would remain strong throughout his life.

Barthes showed great promise as a student and spent the period from 1935 to 1939 at the Sorbonne, where he earned a license in classical letters. He was plagued by ill health throughout this period, suffering from tuberculosis, which often had to be treated in the isolation of sanatoria. His repeated physical breakdowns disrupted his academic career, affecting his studies and his ability to take qualifying examinations. It also kept him out of military service during World War II and, while being kept out of the major French universities meant that he had to travel a great deal for teaching positions, Barthes later professed an intentional avoidance of major degree awarding universities, and did so throughout his career.

His life from 1939 to 1948 was largely spent obtaining a license in grammar and philology, publishing his first papers, taking part in a medical study, and continuing to struggle with his health. In 1948, he returned to purely academic work, gaining numerous short term positions at institutes in France, Romania and Egypt. During this time, he contributed to the leftist Parisian paper Combat, out of which grew his first full length work, Writing Degree Zero (1953). In 1952, Barthes settled at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, where he studied lexicology and sociology. During his seven year period there, he began to write a popular series of bi-monthly essays for the magazine Les Lettres Nouvelles, in which he dismantled myths of popular culture (gathered in the Mythologies collection that was published in 1957).

Barthes spent the early 1960s exploring the fields of semiology and structuralism, chairing various faculty positions around France, and continuing to produce more full length studies. Many of his works challenged traditional academic views of literary criticism and of renowned figures of literature. His unorthodox thinking led to a conflict with another French thinker, Raymond Picard, who attacked the French New Criticism (a label that he inaccurately applied to Barthes) for its obscurity and lack of respect towards France's literary roots. Barthes' rebuttal in Criticism and Truth (1966) accused the old, bourgeois criticism of a lack of concern with the finer points of language and of selective ignorance towards challenging theories, such as Marxism.

By the late 1960s, Barthes had established a reputation for himself. He traveled to the U.S. and Japan, delivering a presentation at Johns Hopkins University. During this time, he wrote his best known work, the 1967 essay "The Death of the Author," which, in light of the growing influence of Jacques Derrida's deconstruction, would prove to be a transitional piece in its investigation of the logical ends of structuralist thought. Barthes continued to contribute with Philippe Sollers to the avant garde literary magazine Tel Quel, which was developing similar kinds of theoretical inquiry to that pursued in Barthes' writings. In 1970, Barthes produced what many consider to be his most prodigious work, the dense, critical reading of Balzac’s Sarrasine entitled S/Z. Throughout the 1970s, Barthes continued to develop his literary criticism; he developed new ideals of textuality and novelistic neutrality. In 1971, he served as visiting professor at the University of Geneva.

In 1975 he wrote an autobiography titled Roland Barthes and in 1977 he was elected to the chair of Sémiologie Littéraire at the Collège de France. In the same year, his mother, Henriette Barthes, to whom he had been devoted, died, aged 85. They had lived together for 60 years. The loss of the woman who had raised and cared for him was a serious blow to Barthes. His last major work, Camera Lucida, is partly an essay about the nature of photography and partly a meditation on photographs of his mother. The book contains many reproductions of photographs, though none of them are of Henriette.

On 25 February 1980, Roland Barthes was knocked down by a laundry van while walking home through the streets of Paris. One month later he succumbed to the chest injuries sustained in that accident.

Barthes's earliest ideas reacted to the trend of existentialist philosophy that was prominent in France during the 1940s, specifically to the figurehead of existentialism, Jean - Paul Sartre. Sartre's What Is Literature? (1947) expresses a disenchantment both with established forms of writing and more experimental, avant garde forms, which he feels alienate readers. Barthes’ response was to try to discover that which may be considered unique and original in writing. In Writing Degree Zero (1953), Barthes argues that conventions inform both language and style, rendering neither purely creative. Instead, form, or what Barthes calls "writing" (the specific way an individual chooses to manipulate conventions of style for a desired effect), is the unique and creative act. A writer's form is vulnerable to becoming a convention, however, once it has been made available to the public. This means that creativity is an on-going process of continual change and reaction. Barthes regarded Albert Camus’s The Stranger as an ideal of this notion, thanks to its lack of embellishment or flair.

In Michelet, a critical analysis of the French historian Jules Michelet, Barthes developed these notions, applying them to a broader range of fields. He argued that Michelet’s views of history and society are obviously flawed. In studying his writings, he continued, one should not seek to learn from Michelet’s claims; rather, one should maintain a critical distance and learn from his errors, since understanding how and why his thinking is flawed will show more about his period of history than his own observations. Similarly, Barthes felt that avant garde writing should be praised for its maintenance of just such a distance between its audience and itself. In presenting an obvious artificiality rather than making claims to great subjective truths, Barthes argued, avant garde writers ensure that their audiences maintain an objective perspective. In this sense, Barthes believed that art should be critical and should interrogate the world, rather than seek to explain it, as Michelet had done.

Barthes's many monthly contributions that were collected in his Mythologies (1957) frequently interrogated specific cultural materials in order to expose how bourgeois society asserted its values through them. For example, the portrayal of wine in French society as a robust and healthy habit is a bourgeois ideal that is contradicted by certain realities (i.e., that wine can be unhealthy and inebriating). He found semiotics, the study of signs, useful in these interrogations. Barthes explained that these bourgeois cultural myths were "second - order signs," or "connotations." A picture of a full, dark bottle is a signifier that relates to a specific signified: a fermented, alcoholic beverage. However, the bourgeoisie relate it to a new signified: the idea of healthy, robust, relaxing experience. Motivations for such manipulations vary, from a desire to sell products to a simple desire to maintain the status quo. These insights brought Barthes in line with similar Marxist theory.

In The Fashion System Barthes showed how this adulteration of signs could easily be translated into words. In this work he explained how in the fashion world any word could be loaded with idealistic bourgeois emphasis. Thus, if popular fashion says that a ‘blouse’ is ideal for a certain situation or ensemble, this idea is immediately naturalized and accepted as truth, even though the actual sign could just as easily be interchangeable with ‘skirt’, ‘vest’ or any number of combinations. In the end Barthes' Mythologies became absorbed into bourgeois culture, as he found many third parties asking him to comment on a certain cultural phenomenon, being interested in his control over his readership. This turn of events caused him to question the overall utility of demystifying culture for the masses, thinking it might be a fruitless attempt, and drove him deeper in his search for individualistic meaning in art.

As Barthes's work with structuralism began to flourish around the time of his debates with Picard, his investigation of structure focused on revealing the importance of language in writing, which he felt was overlooked by old criticism. Barthes's "Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives" is concerned with examining the correspondence between the structure of a sentence and that of a larger narrative, thus allowing narrative to be viewed along linguistic lines. Barthes split this work into three hierarchical levels: ‘functions’, ‘actions’ and ‘narrative’. ‘Functions’ are the elementary pieces of a work, such as a single descriptive word that can be used to identify a character. That character would be an ‘action’, and consequently one of the elements that make up the narrative. Barthes was able to use these distinctions to evaluate how certain key ‘functions’ work in forming characters. For example key words like ‘dark’, ‘mysterious’ and ‘odd’, when integrated together, formulate a specific kind of character or ‘action’. By breaking down the work into such fundamental distinctions Barthes was able to judge the degree of realism given functions have in forming their actions and consequently with what authenticity a narrative can be said to reflect on reality. Thus, his structuralist theorizing became another exercise in his ongoing attempts to dissect and expose the misleading mechanisms of bourgeois culture.

While Barthes found structuralism to be a useful tool and believed that discourse of literature could be formalized, he did not believe it could become a strict scientific endeavor. In the late 1960s, radical movements were taking place in literary criticism. The post - structuralist movement and the deconstructionism of Jacques Derrida were testing the bounds of the structuralist theory that Barthes' work exemplified. Derrida identified the flaw of structuralism as its reliance on a transcendental signifier; a symbol of constant, universal meaning would be essential as an orienting point in such a closed off system. This is to say that without some regular standard of measurement, a system of criticism that references nothing outside of the actual work itself could never prove useful. But since there are no symbols of constant and universal significance, the entire premise of structuralism as a means of evaluating writing (or anything) is hollow.

Such groundbreaking thought led Barthes to consider the limitations not just of signs and symbols, but also of Western culture’s dependency on beliefs of constancy and ultimate standards. He traveled to Japan in 1966 where he wrote Empire of Signs (published in 1970), a meditation on Japanese culture’s contentment in the absence of a search for a transcendental signified. He notes that in Japan there is no emphasis on a great focus point by which to judge all other standards, describing the center of Tokyo, the Emperor’s Palace, as not a great overbearing entity, but a silent and nondescript presence, avoided and unconsidered. As such, Barthes reflects on the ability of signs in Japan to exist for their own merit, retaining only the significance naturally imbued by their signifiers. Such a society contrasts greatly to the one he dissected in Mythologies, which was revealed to be always asserting a greater, more complex significance on top of the natural one.

In the wake of this trip Barthes wrote what is largely considered to be his best known work, the essay “The Death of the Author” (1968). Barthes saw the notion of the author, or authorial authority, in the criticism of literary text as the forced projection of an ultimate meaning of the text. By imagining an ultimate intended meaning of a piece of literature one could infer an ultimate explanation for it. But Barthes points out that the great proliferation of meaning in language and the unknowable state of the author’s mind makes any such ultimate realization impossible. As such, the whole notion of the ‘knowable text’ acts as little more than another delusion of Western bourgeois culture. Indeed the idea of giving a book or poem an ultimate end coincides with the notion of making it consumable, something that can be used up and replaced in a capitalist market. “The Death of the Author” is sometimes considered to be a post - structuralist work, since it moves past the conventions of trying to quantify literature, but others see it as more of a transitional phase for Barthes in his continuing effort to find significance in culture outside of the bourgeois norms. Indeed the notion of the author being irrelevant was already a factor of structuralist thinking.

Since there can be no originating anchor of meaning in the possible intentions of the author, Barthes considers what other sources of meaning or significance can be found in literature. He concludes that since meaning can’t come from the author, it must be actively created by the reader through a process of textual analysis. In his ambitious S/Z (1970), Barthes applies this notion in a massive analysis of a short story by Balzac called Sarrasine. The end result was a reading that established five major codes for determining various kinds of significance, with numerous lexias (a term created by Barthes to describe elements that can take on various meanings for various readers) throughout the text. The codes led him to define the story as having a capacity for plurality of meaning, limited by its dependence upon strictly sequential elements (such as a definite timeline that has to be followed by the reader and thus restricts their freedom of analysis). From this project Barthes concludes that an ideal text is one that is reversible, or open to the greatest variety of independent interpretations and not restrictive in meaning. A text can be reversible by avoiding the restrictive devices that Sarrasine suffered from such as strict timelines and exact definitions of events. He describes this as the difference between the writerly text, in which the reader is active in a creative process, and a readerly text in which they are restricted to just reading. The project helped Barthes identify what it was he sought in literature: an openness for interpretation.

In the late 1970s Barthes was increasingly concerned with the conflict of two types of language: that of popular culture, which he saw as limiting and pigeonholing in its titles and descriptions, and neutral, which he saw as open and noncommittal. He called these two conflicting modes the Doxa and the Para-doxa. While Barthes had shared sympathies with Marxist thought in the past (or at least parallel criticisms), he felt that, despite its anti - ideological stance, Marxist theory was just as guilty of using violent language with assertive meanings, as was bourgeois literature. In this way they were both Doxa and both culturally assimilating. As a reaction to this he wrote The Pleasure of the Text (1975), a study that focused on a subject matter he felt was equally outside of the realm of both conservative society and militant leftist thinking: hedonism. By writing about a subject that was rejected by both social extremes of thought, Barthes felt he could avoid the dangers of the limiting language of the Doxa. The theory he developed out of this focus claimed that while reading for pleasure is a kind of social act, through which the reader exposes him / herself to the ideas of the writer, the final cathartic climax of this pleasurable reading, which he termed the bliss in reading or jouissance, is a point in which one becomes lost within the text. This loss of self within the text or immersion within the text, signifies a final impact of reading that is experienced outside of the social realm and free from the influence of culturally associative language and is thus neutral.

Despite this newest theory of reading, Barthes remained concerned with the difficulty of achieving truly neutral writing, which required an avoidance of any labels that might carry an implied meaning or identity towards a given object. Even carefully crafted neutral writing could be taken in an assertive context through the incidental use of a word with a loaded social context. Barthes felt his past works, like Mythologies, had suffered from this. He became interested in finding the best method for creating neutral writing, and he decided to try to create a novelistic form of rhetoric that would not seek to impose its meaning on the reader. One product of this endeavor was A Lover's Discourse: Fragments in 1977, in which he presents the fictionalized reflections of a lover seeking to identify and be identified by an anonymous amorous other. The unrequited lover’s search for signs by which to show and receive love makes evident illusory myths involved in such a pursuit. The lover’s attempts to assert himself into a false, ideal reality is involved in a delusion that exposes the contradictory logic inherent in such a search. Yet at the same time the novelistic character is a sympathetic one, and is thus open not just to criticism but also understanding from the reader. The end result is one that challenges the reader’s views of social constructs of love, without trying to assert any definitive theory of meaning.

Throughout his career, Barthes had an interest in photography and its potential to communicate actual events. Many of his monthly myth articles in the 50s had attempted to show how a photographic image could represent implied meanings and thus be used by bourgeois culture to infer ‘naturalistic truths’. But he still considered the photograph to have a unique potential for presenting a completely real representation of the world. When his mother, Henriette Barthes, died in 1977 he began writing Camera Lucida as an attempt to explain the unique significance a picture of her as a child carried for him. Reflecting on the relationship between the obvious symbolic meaning of a photograph (which he called the studium) and that which is purely personal and dependent on the individual, that which ‘pierces the viewer’ (which he called the punctum), Barthes was troubled by the fact that such distinctions collapse when personal significance is communicated to others and can have its symbolic logic rationalized. Barthes found the solution to this fine line of personal meaning in the form of his mother’s picture. Barthes explained that a picture creates a falseness in the illusion of ‘what is’, where ‘what was’ would be a more accurate description. As had been made physical through Henriette Barthes's death, her childhood photograph is evidence of ‘what has ceased to be’. Instead of making reality solid, it reminds us of the world’s ever changing nature. Because of this there is something uniquely personal contained in the photograph of Barthes’s mother that cannot be removed from his subjective state: the recurrent feeling of loss experienced whenever he looks at it. As one of his final works before his death, Camera Lucida was both an ongoing reflection on the complicated relations between subjectivity, meaning and cultural society as well as a touching dedication to his mother and description of the depth of his grief.

A posthumous collection of essays was published in 1987 by François Wahl, Incidents. It contains fragments from his journals: his Soirées de Paris (a 1979 extract from his erotic diary of life in Paris); an earlier diary he kept (his erotic encounters with boys in Morocco); and Light of the Sud Ouest (his childhood memories of rural French life). In November 2007, Yale University Press published a new translation into English (by Richard Howard) of Barthes's little known work What is Sport. This work bears a considerable resemblance to Mythologies and was originally commissioned by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation as the text for a documentary film directed by Hubert Aquin.

In February 2009, Éditions du Seuil published Journal de deuil (Journal of Mourning), based on Barthes' files written from 26 November 1977 (the day following his mother's death) up to 15 September 1979, intimate notes on his terrible loss:

The (awesome but not painful) idea that she had not been everything to me. Otherwise I would never have written a work. Since my taking care of her for six months long, she actually had become everything for me, and I totally forgot of ever have written anything at all. I was nothing more than hopelessly hers. Before that she had made herself transparent so that I could write.... Mixing-up of roles. For months long I had been her mother. I felt like I had lost a daughter.

He grieved his mother's death for the rest of his life: "Do not say mourning. It's too psychoanalytic. I'm not in mourning. I'm suffering." and "In the corner of my room where she had been bedridden, where she had died and where I now sleep, in the wall where her headboard had stood against I hanged an icon — not out of faith. And I always put some flowers on a table. I do not wish to travel anymore so that I may stay here and prevent the flowers from withering away."

In 2012 the book Travels in China was published. It consists of his notes from a three week trip to China he undertook with a group from the literary journal Tel Quel in 1974. The experience left him somewhat disappointed, as he found China "not at all exotic, not at all disorienting".

Roland Barthes's incisive criticism contributed to the development of theoretical schools such as structuralism, semiotics, and post - structuralism. While his influence is mainly found in these theoretical fields with which his work brought him into contact, it is also felt in every field concerned with the representation of information and models of communication, including computers, photography, music and literature. One consequence of Barthes' breadth of focus is that his legacy includes no following of thinkers dedicated to modeling themselves after him. The fact that Barthes’ work was ever adapting and refuting notions of stability and constancy means there is no canon of thought within his theory to model one's thoughts upon, and thus no "Barthesism". While this means that his name and ideas lack the visibility of a Marx, Dewey or Freud, Barthes was after all opposed to the notion of adopting inferred ideologies, regardless of their source. In this sense, after his work giving rise to the notion of individualist thought and adaptability over conformity, any thinker or theorist who takes an oppositional stance to inferred meanings within culture can be thought to be following Barthes’ example. Indeed such an individual would have much to gain from the views of Barthes, whose many works remain valuable sources of insight and tools for the analysis of meaning in any given man - made representation.

Readerly and writerly are terms Barthes employs both to delineate one type of literature from another and to implicitly interrogate ways of reading, like positive or negative habits the modern reader brings into one's experience with the text itself. These terms are most explicitly fleshed out in S/Z, while the essay "From Work to Text", from Image — Music — Text (1977) provides an analogous parallel look at the active and passive, postmodern and modern, ways of interacting with a text.

A text that makes no requirement of the reader to "write" or "produce" their own meanings. The reader may passively locate "ready - made" meaning. Barthes writes that these sorts of texts are "controlled by the principle of non - contradiction" (156), that is, they do not disturb the "common sense," or "Doxa," of the surrounding culture. The "readerly texts," moreover, "are products [that] make up the enormous mass of our literature". Within this category, there is a spectrum of "replete literature," which comprises "any classic (readerly) texts" that work "like a cupboard where meanings are shelved, stacked, [and] safeguarded".

A text that aspires to the proper goal of literature and criticism: "... to make the reader no longer a consumer but a producer of the text". Writerly texts and ways of reading constitute, in short, an active rather than passive way of interacting with a culture and its texts. A culture and its texts, Barthes writes, should never be accepted in their given forms and traditions. As opposed to the "readerly texts" as "product," the "writerly text is ourselves writing, before the infinite play of the world is traversed, intersected, stopped, plasticized by some singular system (Ideology, Genus, Criticism) which reduces the plurality of entrances, the opening of networks, the infinity of languages". Thus reading becomes for Barthes "not a parasitical act, the reactive complement of a writing," but rather a "form of work".

Author and scriptor are terms Barthes uses to describe different ways of thinking about the creators of texts. "The author" is our traditional concept of the lone genius creating a work of literature or other piece of writing by the powers of their original imagination. For Barthes, such a figure is no longer viable. The insights offered by an array of modern thought, including the insights of Surrealism, have rendered the term obsolete. In place of the author, the modern world presents us with a figure Barthes calls the "scriptor," whose only power is to combine pre-existing texts in new ways. Barthes believes that all writing draws on previous texts, norms, and conventions, and that these are the things to which we must turn to understand a text. As a way of asserting the relative unimportance of the writer's biography compared to these textual and generic conventions, Barthes says that the scriptor has no past, but is born with the text. He also argues that, in the absence of the idea of an "author - God" to control the meaning of a work, interpretive horizons are opened up considerably for the active reader. As Barthes puts it, "the death of the author is the birth of the reader."

In 1971, Barthes wrote "The Last Happy Writer", the title of which refers to Voltaire. In the essay he commented on the problems of the modern thinker after discovering the relativism in thought and philosophy, discrediting previous philosophers who avoided this difficulty. Disagreeing roundly with Barthes' description of Voltaire, Daniel Gordon, the translator and editor of Candide (The Bedford Series in History and Culture), wrote that "never has one brilliant writer so thoroughly misunderstood another."

Barthes's "A Lover's Discourse: Fragments" was the inspiration for the name of 1980s new wave duo The Lover Speaks.