<Back to Index>

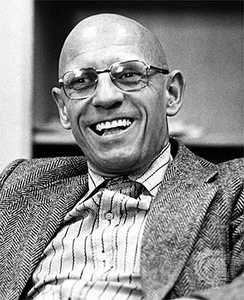

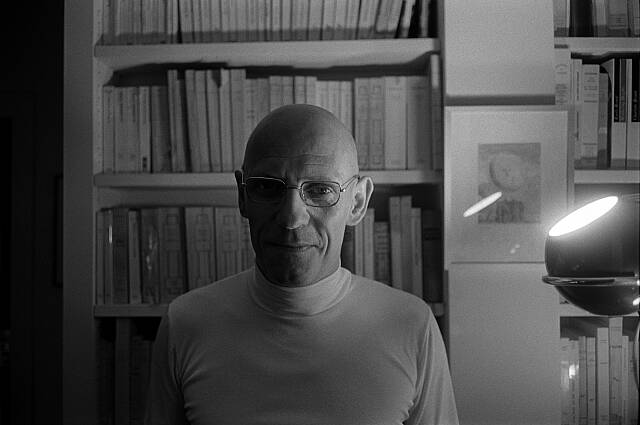

- Philosopher and Social Theorist Michel Foucault, 1926

PAGE SPONSOR

Michel Foucault (born Paul - Michel Foucault) (15 October 1926 – 25 June 1984) was a French philosopher, social theorist and historian of ideas. He held a chair at the Collège de France with the title "History of Systems of Thought", and lectured at both the University at Buffalo and the University of California, Berkeley.

Born into a middle class family in Poitiers, Foucault was educated at the Lycée Henri IV and then the École Normale Supérieure, developing a keen interest in philosophy and coming under the influence of his tutors Jean Hyppolite and Louis Althusser. His first major book, Madness and Civilization (1961), explored the history of the mental institution in Europe, being followed by The Birth of the Clinic (1963), a discussion of the development of Europe's medical profession.

In the 1960s, Foucault was associated with structuralism, a theoretical movement in social anthropology from which he later distanced himself. He also rejected the post - structuralist and postmodernist labels later attributed to him, preferring to classify his thought as a critical history of modernity rooted in Immanuel Kant. A left wing political activist, he was involved in several protest movements, among others for prisoner's rights. Foucault died in Paris of neurological problems compounded by the HIV / AIDS virus; he was the first famous figure in France to have died from the virus, with his partner Daniel Defert founding the AIDES charity in his memory.

Foucault is best known for his critical studies of social institutions, most notably psychiatry, social anthropology of medicine, the human sciences and the prison system, as well as for his work on the history of human sexuality. His writings on power, knowledge and discourse have been widely influential in academic circles. His project was particularly influenced by Nietzsche, his "genealogy of knowledge" being a direct allusion to Nietzsche's "genealogy of morality". In a late interview he definitively stated: "I am a Nietzschean." Foucault was listed as the most cited scholar in the humanities in 2007 by the ISI Web of Science.

Paul - Michel Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in the small town of Poitiers, west - central France, as the second of three children to a prosperous and socially conservative upper middle class family. He had been named after his father, Dr. Paul Foucault, as was the family tradition, but his mother insisted on the addition of the double - barreled "Michel"; while he would always be referred to as "Paul" at school, he always expressed a preference for "Michel". His father (1893 – 1959) was a successful local surgeon, having been born in Fontainebleau before moving to Poitiers, where he set up his own practice and married local woman Anne Malapert. She was the daughter of prosperous surgeon Dr. Prosper Malapert, who owned a private practice in Poitiers and taught anatomy at the University of Poitiers' School of Medicine. Paul Foucault eventually took over his father - in - law's medical practice as well, while his wife took charge of their large mid 19th century house, Le Piroir, located at the village of Vendeuvre - du - Poitou 15 kilometers from the town. Together the couple had 3 children, a girl named Francine and two boys, Paul - Michel and Denys, all of whom shared the same fair hair and bright blue eyes. These children were raised to be nominal Roman Catholics, attending mass at the Church of Saint - Porchair, with Michel briefly becoming an altar boy, although none were devout. He would later claim that as a child he was "actually very stupid", only developing his intelligence through doing the homework of other boys whom he was attracted to; he would later comment that "all the rest of my life I've been trying to do intellectual things that would attract beautiful boys."

In later life, Foucault would reveal very little about his childhood. Describing himself as a "juvenile delinquent", he noted that his father was a "bully" who would sternly punish him for his misbehavior. In 1930, Foucault began his schooling at the local Lycée Henry IV despite the fact that he was under six, and he would undertake two years of elementary education before entering the main lycée, where he stayed until 1936. He then undertook his first four years of secondary education at the same establishment, excelling in French, Greek, Latin and history but doing poorly at mathematics. In 1939, the Second World War broke out and France was occupied by the armies of Nazi Germany until 1945; his parents opposed the occupation and the Vichy regime who collaborated with them, but did not join the French Resistance. In 1940, Foucault's mother took him from his previous school and enrolled him in the Collège Saint - Stanislas, a strict Roman Catholic institution run by the Jesuits; here, he remained lonely, with few friends. Describing his years there as the "ordeal", he nevertheless excelled academically, particularly in the fields of philosophy, history and literature. In 1942, he entered the terminale where he focused on the study of philosophy, earning his baccalauréat in 1943. That year, he then returned to the local Lycée Henry IV, where he studied history and philosophy for a year.

Rejecting his father's wishes to become a surgeon, in 1945 Foucault traveled to the French capital of Paris, where he enrolled in one of the country's most prestigious secondary schools, which was also known as the Lycée Henri IV. Here, he briefly studied under the philosopher Jean Hyppolite (1907 – 1968), an existentialist and expert on the work of 19th century German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770 – 1831). Hyppolite devoted his energies to uniting the existentialist theories then in vogue among French philosophers with the dialectical theories of Hegel and Karl Marx (1818 – 1883); these ideas influenced the young Foucault, who would adopt Hypollite's conviction that philosophy must be developed through a study of history. As a result, in ensuing years he would defend those who proposed a Marxist interpretation of history coupled with the existentialist view of the human individual.

Attaining excellent results at the school, in the autumn of 1946 Foucault was admitted to the elite École Normale Supérieure (ENS); in order to get in, he had to undertake a series of exams and oral interrogation by Georges Canguilhem and Pierre - Maxime Schuhl. Of the hundred students entering the ENS, Foucault was ranked fourth based on his entry results, and encountered the highly competitive nature of the institution. Like most of his classmates, he was housed in the school's communal dormitories, located on the Parisian Rue d'Ulm. He remained largely unpopular among the other students, and spent much of his time alone, reading voraciously. His fellow students noted him for his love of violence and the macabre; he had decorated his bedroom with the images of torture and war drawn during the Napoleonic Wars by Spanish artist Francisco Goya (1746 – 1828), and on one occasion chased one of his classmates while brandishing a dagger. Prone to self - harm, in 1948 Foucault allegedly undertook a failed suicide attempt, for which his father sent him to see the psychiatrist Jean Delay (1907 – 1987) at the Hôpital Sainte - Anne. Obsessed with the idea of self - mutilation and suicide, Foucault would attempt the latter several times in ensuing years, and praised the act of killing oneself in a number of his later writings. The École Normale Supérieure's doctor examined Foucault's state of mind, suggesting that his suicidal tendencies emerged from the distress surround his homosexuality, which at the time was legal but socially taboo in France. At the time, Foucault engaged in homosexual activity with men whom he encountered in the underground Parisian gay scene, also indulging in drug use; according to biographer James Miller, he particularly enjoyed the thrill and sense of danger that these activities offered him.

Although studying an array of subjects at the school, Foucault's particular interest was soon drawn to philosophy, reading not only the works of Hegel and Marx that he had been exposed to by Hyppolite but also studying the writings of the philosophers Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804), Edmund Husserl (1859 – 1938) and most significantly, Martin Heidegger (1889 – 1976). He also began to read the works of philosopher Gaston Bachelard (1884 – 1962), taking a particular interest in his work exploring the history of science. In 1948, the philosopher Louis Althusser (1918 – 1980) became a tutor at the École Normale Supérieure. A Marxist, he proved to be an influence both on Foucault and a number of other students, encouraging them to join the French Communist Party (Parti communiste français - PCF), which Foucault duly did in 1950. Despite this, he never became particularly active in any of its activities, and never adopted an orthodox Marxist viewpoint, refuting concepts such as class struggle which were central to Marxist thought. He would soon become dissatisfied with the bigotry that he experienced within the party's ranks; he personally faced homophobia and was also appalled by the anti - semitism exhibited in the Doctors' plot that occurred in the Soviet Union. He left the Communist Party in 1953, but would remain a friend and defender of Althusser for the rest of his life. He passed his agrégation in philosophy on the second try, in 1951. Excused from national service on medical grounds, he decided that he wanted to go on and study for a doctorate at the Fondation Thiers.

Leaving education, Foucault embarked on a variety of odd jobs in research and teaching. From 1951 to 1955, he worked as an instructor in psychology at the École Normale Supérieure at the invitation of Althusser. After a brief period lecturing at the École Normale, he took up a position at the Université Lille Nord de France, where from 1953 to 1954 he taught psychology. He also spent much of his time devoted to his own research in the history of psychology and psychiatry, visiting the Bibliothèque Nationale every day to read the work of psychologists like Ivan Pavlov (1849 – 1936), Jean Piaget (1896 – 1980) and Karl Jaspers (1883 – 1969). Undertaking research at the psychiatric institute of the Hôpital Sainte - Anne, he became an unofficial intern, studying the relationship between the doctors and the patients and aiding the experiments in the electroencephalographic laboratory. Foucault adopted many of the theories of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939), undertaking psychoanalytical interpretation of his dreams. It was also in this period of his life that he changed his name from "Paul - Michel" to "Michel", thereby rejecting the influence of his father, whom he detested.

Embracing the Parisian avant garde, Foucault entered into a romantic relationship with the composer Jean Barraqué (1928 – 1973), a prominent advocate of serialism. Together, they wished to push the boundaries of the human mind, believing that in doing so they could produce their greatest work; making heavy use of drugs, they also engaged in sado - masochistic sexual activity. In August 1953, Foucault and Barraqué went on a holiday to Italy, where the philosopher immersed himself in Untimely Meditations (1873 – 1876), a collection of four essays authored by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900). Later describing Nietzsche's work as "a revelation", he felt that reading the book deeply affected him, and he subsequently "broke with my life" as he had formerly experienced it. Foucault would subsequently experience a groundbreaking self - revelation when watching a Parisian performance of Samuel Beckett's new play, Waiting for Godot, in 1953.

Interested in the work of Swiss psychologist Ludwig Binswanger (1881 – 1966), Foucault aided a young woman named Jacqueline Verdeaux in translating his works into French. Foucault was particularly interested in the work that Binswager had undertaken in studying a woman named Ellen West who, like himself, had a deep obsession with the idea of suicide, eventually killing herself. In 1954, Foucault authored an introduction to one of Binswager's papers, "Dream and Existence", in which the Frenchman put forward the idea that dreams constituted "the birth of the world" or "the heart laid bare", expressing the mind's deepest desires. In 1954 Foucault also published his first book, Mental Illness and Personality (Maladie mentale et personnalité), in which he exhibited his influence from both Marxist and Heideggerian thought, covering a wide range of subject matter from the reflex psychology of Pavlov to the classic psychoanalysis of Freud. Biographer James Miller would later note that while the book exhibited "erudition and evident intelligence", it lacked the "kind of fire and flair" which Foucault exhibited in his subsequent works.

Taking an interest in literature, Foucault was an avid reader of the book reviews authored by the philosopher Maurice Blanchot (1907 – 2003), which were published in the Nouvelle Revue Française. Becoming enamored with Blanchot's literary style and critical theories, in several later works he adopted Blanchot's technique of "interviewing" himself. Foucault also came across Hermann Broch's 1945 novel The Death of Virgil at this time, a work that came to obsess both him and Barraqué. While the latter attempted to convert the work into an epic opera, Foucault admired Broch's text for its portrayal of death as an affirmation of life. Foucault would spend the next five years working abroad, first in the Swedish city of Uppsala, and then in Warsaw, Poland, and then finally in Frankfurt, West Germany. In spring 1956, Barraqué would break from his relationship with Foucault, announcing that he wanted to leave the "vertigo of madness".

Foucault returned to France in 1960 to complete his doctorate and take up a post in philosophy at the University of Clermont - Ferrand. There he met philosopher Daniel Defert, who would become his partner of twenty years. In 1961 he earned his doctorate by submitting two theses (as is customary in France): a "major" thesis entitled Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique (Madness and Insanity: History of Madness in the Classical Age) and a "secondary" thesis that involved a translation of, and commentary on Kant's Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. The academics responsible for reviewing his work were concerned about the unconventional nature of his major thesis; Henri Gouhier, one of the reviewers, noted that it was not a conventional work of history, making sweeping generalizations without sufficient generalizations, and that Foucault clearly "thinks in allegories".

Madness and Civilization would be published in French in May 1961 by the company Plon. Foucault had initially received an offer of publication from the Presses Universitaires de France, but he wanted his work to be published by a popular rather than an academic press, so that it would reach a wider audience. Hoping that his work would be picked up by Gallimard, the publishers of Jean - Paul Sartre's influential bestseller, Being and Nothingness, he was perturbed when they rejected him, instead selecting Plon. In 1964, a heavily abridged version was published as a mass market paperback, which was then translated into English for publication the following year. In the book, Foucault dealt with the manner in which Western European society had dealt with madness, arguing that it was a social construct distinct from mental illness. The work contains a number of allusions and references to the work of French poet and playwright Antonin Artaud, (1896 – 1948) who exerted a strong influence over Foucualt's thought at the time.

Upon publication, Madness and Civilization was critically acclaimed in France, receiving praise from the likes of Maurice Blochot, Michel Serres, Roland Barthes, Gaston Bachelard and Fernand Braudel. The work did however come under attack from a young philosopher who had been a student on Foucault's psychology course at the École Normale Supérieure, Jacques Derrida (1930 – 2004). Derrida's critique came in the form of a lecture he gave on "The Cogito and the History of Madness" at the University of Paris on 4 March 1963, accusing Foucault of advocating metaphysics. Responding to the criticism with a vicious retort, Foucault ignored some of Derrida's points, focusing in on a criticism of how the younger philosophy had interpreted the work of René Descartes. The two would remain bitter rivals until 1981.

In 1963 he published Naissance de la Clinique (Birth of the Clinic), Raymond Roussel, and a reissue of his 1954 volume (now entitled Maladie mentale et psychologie or, in English, "Mental Illness and Psychology"). After Defert was posted to Tunisia for his military service, Foucault moved to a position at the University of Tunis in 1965. He published Les Mots et les choses (The Order of Things) during the height of interest in structuralism in 1966, and Foucault was quickly grouped with scholars such as Jacques Lacan, Claude Lévi - Strauss, and Roland Barthes as the newest, latest wave of thinkers set to topple the existentialism popularized by Jean - Paul Sartre. Foucault made a number of skeptical comments about Marxism, which outraged a number of left wing critics, but later firmly rejected the "structuralist" label. He was still in Tunis during the May 1968 student riots, where he was profoundly affected by a local student revolt earlier in the same year. In the Autumn of 1968 he returned to France, where he published L'archéologie du savoir (The Archaeology of Knowledge) – a methodological treatise that included a response to his critics – in 1969.

In the aftermath of 1968, the French government created a new experimental university, Paris VIII, at Vincennes and appointed Foucault the first head of its philosophy department in December of that year. Foucault appointed mostly young leftist academics (such as Judith Miller) whose radicalism provoked the Ministry of Education, who objected to the fact that many of the course titles contained the phrase "Marxist - Leninist," and who decreed that students from Vincennes would not be eligible to become secondary school teachers. Foucault notoriously also joined students in occupying administration buildings and fighting with police.

Foucault's tenure at Vincennes was short lived, as in 1970 he was elected to France's most prestigious academic body, the Collège de France, as Professor of the History of Systems of Thought. His political involvement increased, and his partner Defert joined the ultra - Maoist Gauche Proletarienne (GP). Foucault helped found the Prison Information Group (French: Groupe d'Information sur les Prisons or GIP) to provide a way for prisoners to voice their concerns. This coincided with Foucault's turn to the study of disciplinary institutions, with a book, Surveiller et Punir (Discipline and Punish), which "narrates" the micro - power structures that developed in Western societies since the 18th century, with a special focus on prisons and schools.

In the late 1970s, political activism in France trailed off with the disillusionment of many left wing intellectuals. A number of young Maoists abandoned their beliefs to become the so-called New Philosophers, often citing Foucault as their major influence, a status Foucault had mixed feelings about. Foucault in this period embarked on a six volume project The History of Sexuality, which he never completed. Its first volume was published in French as La Volonté de Savoir (1976), then in English as The History of Sexuality: An Introduction (1978). The second and third volumes did not appear for another eight years, and they surprised readers by their subject matter (classical Greek and Latin texts), approach and style, particularly Foucault's focus on the human subject, a concept that some mistakenly believed he had previously neglected.

Foucault began to spend more time in the United States, at the University at Buffalo (where he had lectured on his first ever visit to the United States in 1970) and especially at UC Berkeley. In 1975 he took LSD at Zabriskie Point in Death Valley National Park, later calling it the best experience of his life.

In 1979 Foucault made two tours of Iran, undertaking extensive interviews with political protagonists in support of the new interim government established soon after the Iranian Revolution. In the tradition of Nietzsche and Georges Bataille, Foucault had embraced the artist who pushed the limits of rationality, and he wrote with great passion in defense of irrationalities that broke boundaries. In 1978, Foucault found such transgressive powers in the revolutionary figures Ayatollah Khomeini, Ali Shariati and the millions who risked death as they followed them in the course of the revolution. Both Foucault and the revolutionaries were highly critical of modernity and sought a new form of politics, they both also looked up to those who risked their lives for ideals; and both looked to the past for inspiration. Later on when Foucault went to Iran “to be there at the birth of a new form of ideas,” he wrote that the new “Muslim” style of politics could signal the beginning of a new form of “political spirituality,” not just for the Middle East, but also for Europe, which had adopted the practice of secular politics ever since the French Revolution. Foucault recognized the enormous power of the new discourse of militant Islam, not just for Iran, but for the world. He wrote:

As an Islamic movement, it can set the entire region afire, overturn the most unstable regimes, and disturb the most solid. Islam which is not simply a religion, but an entire way of life, an adherence to a history and a civilization, has a good chance to become a gigantic powder keg, at the level of hundreds of millions of men. . . Indeed, it is also important to recognize that the demand for the 'legitimate rights of the Palestinian people' hardly stirred the Arab peoples. What it be if this cause encompassed the dynamism of an Islamic movement, something much stronger than those with a Marxist, Leninist or Maoist character? (“A Powder Keg Called Islam”)

During his two trips to Iran, Foucault was commissioned as a special correspondent of a leading Italian newspaper and his articles appeared on the front page of that paper. His many essays on Iran, published in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, only appeared in French in 1994 and then in English in 2005. These essays caused some controversy, with some commentators arguing that Foucault was insufficiently critical of the new regime. The more common attempts to bracket out Foucault's writings on Iran as "miscalculations," reminds some authors of what Foucault himself had criticized in his well known 1969 essay, "What is an Author?" Foucault believed that when we include certain works in an author's career and exclude others that were written in a "different style," or were "inferior" (Foucault 1969, 111), we create a stylistic unity and a theoretical coherence. This is done by privileging certain writings as authentic and excluding others that do not fit our view of what the author ought to be: "The author is therefore the ideological figure by which one marks the manner in which we fear the proliferation of meaning" (Foucault 1969, 110). This controversy is frequently discussed in the Foucault literature.

In the philosopher's later years, interpreters of Foucault's work attempted to engage with the problems presented by the fact that the late Foucault seemed in tension with the philosopher's earlier work. When this issue was raised in a 1982 interview, Foucault remarked "When people say, 'Well, you thought this a few years ago and now you say something else,' my answer is… [laughs] 'Well, do you think I have worked hard all those years to say the same thing and not to be changed?'" He refused to identify himself as a philosopher, historian, structuralist or Marxist, maintaining that "The main interest in life and work is to become someone else that you were not in the beginning." In a similar vein, he preferred not to state that he was presenting a coherent and timeless block of knowledge; he rather desired his books "to be a kind of tool box others can rummage through to find a tool they can use however they wish in their own area… I don't write for an audience, I write for users, not readers."

During his trips to California, Foucault spent many evenings in the gay scene of the San Francisco Bay Area. He frequented a number of sado - masochistic bathhouses, engaging in sexual intercourse with other patrons. He would praise sado - masochistic activity in interviews with the gay press, describing it as "the real creation of new possibilities of pleasure, which people had no idea about previously." The American academic James Miller would later claim that Foucault's experiences in the gay sadomasochism community during the time he taught at Berkeley directly influenced his political and philosophical works. Miller's ideas have been rebuked by certain Foucault scholars as being either simply misdirected, a sordid reading of his life and works, or as a politically motivated, intentional misreading.

At one point, Foucault contracted the HIV virus, which would eventually develop into AIDS. Little was known of the disease at the time; the first cases had only been identified in 1980, and it had only been named in 1982. In the summer of 1983, he noticed that he had a persistent dry cough; friends in Paris became concerned that he may have contracted the HIV / AIDS virus then sweeping the San Francisco gay population, but Foucault insisted that he had nothing more than a pulmonary infection that would clear up when he spent the autumn of 1983 in California. It was only when hospitalized that Foucault was diagnosed with AIDS; placed on antibiotics, he was able to deliver a final set of lectures at the Collège de France. Foucault entered Paris' Hôpital de la Salpêtrière – the same institution that he had studied in Madness and Civilisation – on 9 June 1984, with neurological symptoms complicated by septicemia. He died in the hospital at 1:15pm on 25 June.

On 26 June, the newspaper Libération – associated with Foucault for much of his life – announced his death, also highlighting the rumor that it had been brought on by AIDS. The following day, Le Monde publicly issued a medical bulletin that had been cleared by his family; it made no reference to the HIV / AIDS virus. On 29 June, Foucault's la levée du corps ceremony was held, in which the coffin was carried from the morgue. Taking place in the rear courtyard of the Hôpital de la Salpêtriêre, it was attended by hundreds of admirers who had seen the event advertised in Le Monde, including left wing activists like Yves Montand and Simone Signoret and academics such as Jacques Derrida, Paul Veyne, Pierre Bourdieu and Georges Dumézil. Foucault's friend Gilles Deleuze gave a speech, with the words coming from the preface to the final two volumes of The History of Sexuality.

Soon after his death, Foucault's partner Daniel Defert founded the first national AIDS organization in France, which he called AIDES; a pun on the French language word for "help" (aide) and the English language acronym for the disease. On the second anniversary of Foucault's death, Defert agreed to publicly announce that Foucault's death was AIDS related, doing so in the California based gay magazine, The Advocate.

The English edition of Madness and Civilization is an abridged version of Folie et déraison: Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, originally published in 1961. A full English translation titled The History of Madness has since been published by Routledge in 2006. "Folie et deraison" originated as Foucault's doctoral dissertation; this was Foucault's first major book, mostly written while he was the Director of the Maison de France in Sweden. It examines ideas, practices, institutions, art, and literature relating to madness in Western history.

Foucault begins his history in the Middle Ages, noting the social and physical exclusion of lepers. He argues that with the gradual disappearance of leprosy, madness came to occupy this excluded position. The ship of fools in the 15th century is a literary version of one such exclusionary practice, namely that of sending mad people away in ships. In 17th century Europe, in a movement Foucault famously calls the "Great Confinement," "unreasonable" members of the population were institutionalized. In the 18th century, madness came to be seen as the reverse of Reason, and, finally, in the 19th century as mental illness.

Foucault also argues that madness was silenced by Reason, losing its power to signify the limits of social order and to point to the truth. He examines the rise of scientific and "humanitarian" treatments of the insane, notably at the hands of Philippe Pinel and Samuel Tuke who he suggests started the conceptualization of madness as 'mental illness'. He claims that these new treatments were in fact no less controlling than previous methods. Pinel's treatment of the mad amounted to an extended aversion therapy, including such treatments as freezing showers and use of a straitjacket. In Foucault's view, this treatment amounted to repeated brutality until the pattern of judgment and punishment was internalized by the patient.

Foucault's second major book, The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (Naissance de la clinique: une archéologie du regard médical) was published in 1963 in France, and translated to English in 1973. Picking up from Madness and Civilization, The Birth of the Clinic traces the development of the medical profession, and specifically the institution of the clinique (translated as "clinic", but here largely referring to teaching hospitals). Its motif is the concept of the medical regard (translated by Alan Sheridan as "medical gaze"), traditionally limited to small, specialized institutions such as hospitals and prisons, but which Foucault examines as subjecting wider social spaces, governing the population en masse.

Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel was published in 1963, and translated into English in 1986. It is Foucault's only book length work on literature. Foucault described it as "by far the book I wrote most easily, with the greatest pleasure, and most rapidly." Foucault explores theory, criticism and psychology with reference to the texts of Raymond Roussel, one of the fathers of experimental writing.

Foucault's Les Mots et les choses. Une archéologie des sciences humaines was published in 1966. It was translated into English in 1970 under the title The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Foucault had preferred L'Ordre des choses for the original French title, but changed it as there was already another book by that name. The work broadly aims to provide an anti - humanist excavation of the human sciences, such as sociology and psychology. It opens with an extended discussion of Diego Velázquez's painting Las Meninas and the painting's complex arrangement of sight - lines, hiddenness and appearance. It then develops its central thesis: all periods of history have possessed specific underlying conditions of truth that constituted what could be expressed as discourse (for example art, science, culture, etc.). Foucault argues that these conditions of discourse have changed over time, in major and relatively sudden shifts, from one period's episteme to another. Foucault's Nietzschean critique of Enlightenment values in Les mots et les choses has been very influential in cultural studies and social work scholarship. It is in this book that Foucault claims that "man is only a recent invention" and that the "end of man" is at hand. The book made Foucault a prominent intellectual figure in France.

Published in 1969, this volume was Foucault's main excursion into methodology, written as an outcome of discussions with the French Circle of Epistemology. Taking its point of departure in the French epistemological tradition, it makes few references to Anglo - American analytical philosophy except as to speech act theory, from which Foucault distances himself.

Foucault directs his analysis toward the "statement" (énoncé), which is the rules that render an expression (that is, a phrase, a proposition or a speech act ) discursively meaningful. This concept of meaning differs from the concept of signification: Though an expression is signifying, for instance "The gold mountain is in California"), it may nevertheless be discursively meaningless and therefore have no existence within a certain discourse. For this reason, the "statement" is an existence function for discursive meaning. Being rules, the "statement" has a very special meaning in the Archaeology: it is not the expression itself, but the rules which make an expression discursively meaningful. These rules are not the syntax and semantics that makes an expression signifying. It is additional rules. In contrast to structuralists, Foucault demonstrates that the semantic and syntactic structures do not suffice to determine the discursive meaning of an expression. Depending on whether or not it complies with these rules of discursive meaning, a grammatically correct phrase may lack discursive meaning or, inversely, a grammatically incorrect sentence may be discursively meaningful - even meaningless letters, e.g. "QWERT" may have discursive meaning. Thus, the meaning of expressions depends on the conditions in which they emerge and exist within a field of discourse; the discursive meaning of an expression is reliant on the succession of statements that precede and follow it. In short, the "statements" Foucault analyzed are not propositions, phrases, or speech acts. Rather, "statements" constitute a network of rules establishing which expressions are discursively meaningful, and these rules are the preconditions for signifying propositions, utterances, or speech acts to have discursive meaning. However, "statements" are also 'events', because, like other rules, they appear (or disappear) at some time.

Foucault aims his analysis towards a huge organized dispersion of statements, called discursive formations. Foucault reiterates that the analysis he is outlining is only one possible procedure, and that he is not seeking to displace other ways of analyzing discourse or render them as invalid.

According to Dreyfus and Rabinow, Foucault not only brackets out issues of truth (cf. Husserl), he also brackets out issues of meaning. However, Foucault does not bracket out discursive meaning. But, focusing on discursive meaning, Foucault did not look for a deeper meaning underneath discourse or for the source of meaning in some transcendental subject. Instead, Foucault analyzes the discursive and practical conditions for the existence of truth and discursive meaning. To show the principles of production of truth and discursive meaning in various discursive formations, he details how truth claims emerge during various epochs on the basis of what was actually said and written during these periods. He particularly describes the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, and the 20th century. He strives to avoid all interpretation and to depart from the goals of hermeneutics. This does not mean that Foucault denounces truth and discursive meaning, but just that truth and discursive meaning depend on the historical discursive and practical means of truth and meaning production. For instance, although they were radically different during Enlightenment as opposed to Modernity, there were indeed discursive meaning, truth and correct treatment of madness during both epochs (Madness and Civilization). This posture allows Foucault to denounce a priori concepts of the nature of the human subject and focus on the role of discursive practices in constituting subjectivity.

Foucault's relation to structuralism seems somewhat ambiguous. However, in the preface to the English translation of Les Mots et les Choses (1970), he clearly disavowed structuralism:

In France certain half - witted 'commentators' persist in labeling me a 'structuralist'. I have been unable to get it into their tiny minds that I have used none of the methods, concepts, or key terms that characterize structural analysis.

Whereas structuralists search for homogeneity in a discursive entity, Foucault focuses on differences. Instead of asking what constitutes the specificity of European thought he asks what constitutes the differences developed within it and over time. Therefore, as a historical method, he refuses to examine statements outside of their historical context: the discursive formation. The meaning of a statement depends on the general rules that characterize the discursive formation to which it belongs. A discursive formation continually generates new statements, and some of these usher in changes in the discursive formation that may or may not be adopted. Therefore, to describe a discursive formation, Foucault also focuses on expelled and forgotten discourses that never happened to change the discursive formation (the genealogical analysis). Their differences from the dominant discourse also describe it. In this way one can describe specific systems that determine which types of statements emerge. In his Foucault (1986), Deleuze describes The Archaeology of Knowledge as "the most decisive step yet taken in the theory - practice of multiplicities."

Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison was translated into English in 1977, from the French Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison, published in 1975. The book opens with a graphic description of the brutal public execution in 1757 of Robert - François Damiens, who attempted to kill Louis XV. Against this it juxtaposes a colorless prison timetable from just over 80 years later. Foucault then inquires how such a change in French society's punishment of convicts could have developed in such a short time. These are snapshots of two contrasting types of Foucault's "Technologies of Punishment." The first type, "Monarchical Punishment," involves the repression of the populace through brutal public displays of executions and torture. The second, "Disciplinary Punishment," is what Foucault says is practiced in the modern era. Disciplinary punishment gives "professionals" (psychologists, program facilitators, parole officers, etc.) power over the prisoner, most notably in that the prisoner's length of stay depends on the professionals' judgment. Foucault goes on to argue that Disciplinary punishment leads to self - policing by the populace as opposed to brutal displays of authority from the Monarchical period.

Foucault argues between the 17th and 18th centuries a new, more subtle form of power was being exercised transnationally. He calls this form of power discipline. Soldiers could be made and formed rather than just being chosen because of their natural characteristics. Knowledge and power are central to Foucault's analysis. He questions common concepts like justice or equality and asks where these concepts originated and who they benefit. The process of observing and evaluating individuals leads to more and more knowledge about peoples.

Foucault also compares modern society with Jeremy Bentham's "Panopticon" design for prisons (which was unrealized in its original form, but nonetheless influential): in the Panopticon, a single guard can watch over many prisoners while the guard remains unseen. Ancient prisons have been replaced by clear and visible ones, but Foucault cautions that "visibility is a trap." It is through this visibility, Foucault writes, that modern society exercises its controlling systems of power and knowledge (terms Foucault believed to be so fundamentally connected that he often combined them in a single hyphenated concept, "power - knowledge"). Increasing visibility leads to power located on an increasingly individualized level, shown by the possibility for institutions to track individuals throughout their lives. Foucault suggests that a "carceral continuum" runs through modern society, from the maximum security prison, through secure accommodation, probation, social workers, police and teachers, to our everyday working and domestic lives. All are connected by the (witting or unwitting) supervision (surveillance, application of norms of acceptable behavior) of some humans by others.

Three volumes of The History of Sexuality were published before Foucault's death in 1984. The first and most referenced volume, The Will to Knowledge (previously known as An Introduction in English – Histoire de la sexualité, 1: la volonté de savoir in French) was published in France in 1976, and translated in 1977, focusing primarily on the last two centuries, and the functioning of sexuality as an analytics of power related to the emergence of a science of sexuality (scientia sexualis) and the emergence of biopower in the West. In this volume he attacks the "repressive hypothesis", the widespread belief that we have "repressed" our natural sexual drives, particularly since the 19th century. He proposes that what is thought of as "repression" of sexuality actually constituted sexuality as a core feature of human identities, and produced a proliferation of discourse on the subject.

The second two volumes, The Use of Pleasure (Histoire de la sexualité, II: l'usage des plaisirs) and The Care of the Self (Histoire de la sexualité, III: le souci de soi) dealt with the role of sex in Greek and Roman antiquity. Both were published in 1984, the year of Foucault's death, with the second volume being translated in 1985, and the third in 1986. In his lecture series from 1979 to 1980 Foucault extended his analysis of government to its 'wider sense of techniques and procedures designed to direct the behavior of men', which involved a new consideration of the 'examination of conscience' and confession in early Christian literature. These themes of early Christian literature seemed to dominate Foucault's work, alongside his study of Greek and Roman literature, until the end of his life. However, Foucault's death left the work incomplete, and the planned fourth volume of his History of Sexuality on Christianity was never published. The fourth volume was to be entitled Confessions of the Flesh (Les aveux de la chair). The volume was almost complete before Foucault's death and a copy of it is privately held in the Foucault archive. It cannot be published under the restrictions of Foucault's estate.

In 1970 Foucault began a schedule of weekly public lectures and seminars during the first three months of each year at the Collège de France as the condition of his tenure as professor there. These continued each year except 1977 until his death in 1984. The lectures were tape recorded and Foucault's notes also survive. In 1997 the lectures began to be published in French. Of the first nine volumes to be published, eight have been translated into English: Psychiatric Power 1973 – 1974, Abnormal 1974 – 1975, Society Must Be Defended 1975 – 1976, Security, Territory, Population 1977 – 1978, The Birth of Biopolitics 1978 - 1979, The Hermeneutics of the Subject 1981 – 1982, The Government of Self and Others 1982 – 1983, and The Courage of Truth 1983 - 1984.

Society Must Be Defended and Security, Territory, Population pursued an analysis of the broader relationship between security and biopolitics, explicitly politicizing the question of the birth of humankind raised in The Order of Things. In Security, Territory, Population, Foucault outlines his theory of governmentality, and demonstrates the distinction between sovereignty, discipline, and governmentality as distinct modalities of state power. He argues that governmental state power can be genealogically linked to the 17th century state philosophy of raison d'etat and, ultimately, to the medieval Christian 'pastoral' concept of power. Notes of some of Foucault's lectures from University of California, Berkeley in 1983 have also appeared as Fearless Speech.

Foucault's discussions on power and discourse have inspired many critical theorists. Critical theorists believe that Foucault's analysis of power structures could aid the struggle against inequality. They claim that through discourse analysis, power structures may be uncovered and analyzed for their truth claims. This is one of the ways that Foucault's work is linked to critical theory.

Some theorists have questioned the extent to which Foucault may be regarded as an ethical 'neo - anarchist', the self - appointed architect of a "new politics of truth", or, to the contrary, a nihilistic and disobligating 'neo - functionalist'. Jean - Paul Sartre, in a review of The Order of Things, described the non - Marxist Foucault as "the last rampart of the bourgeoisie."

Jürgen Habermas has described Foucault as a "crypto - normativist", covertly reliant on the very Enlightenment principles he attempts to deconstruct. Central to this problem is the way Foucault seemingly attempts to remain both Kantian and Nietzschean in his approach:

Foucault discovers in Kant, as the first philosopher, an archer who aims his arrow at the heart of the most actual features of the present and so opens the discourse of modernity ... but Kant's philosophy of history, the speculation about a state of freedom, about world - citizenship and eternal peace, the interpretation of revolutionary enthusiasm as a sign of historical 'progress toward betterment' – must not each line provoke the scorn of Foucault, the theoretician of power? Has not history, under the stoic gaze of the archaeologist Foucault, frozen into an iceberg covered with the crystals of arbitrary formulations of discourse?

— Habermas Taking Aim at the Heart of the Present 1984

Philosopher Richard Rorty has argued that Foucault's 'archaeology of knowledge' is fundamentally negative, and thus fails to adequately establish any 'new' theory of knowledge per se. Rather, Foucault simply provides a few valuable maxims regarding the reading of history:

As far as I can see, all he has to offer are brilliant redescriptions of the past, supplemented by helpful hints on how to avoid being trapped by old historiographical assumptions. These hints consist largely of saying: "do not look for progress or meaning in history; do not see the history of a given activity, of any segment of culture, as the development of rationality or of freedom; do not use any philosophical vocabulary to characterize the essence of such activity or the goal it serves; do not assume that the way this activity is presently conducted gives any clue to the goals it served in the past."

— Rorty Foucault and Epistemology, 1986

Roger Scruton described Foucault as an example of a "fraud" who exploited the known difficulties of philosophy to "disguise unexamined premises as hard - won conclusions".