<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl, 1859

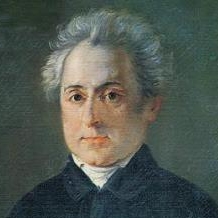

- Poet Dionysios Solomos, 1798

- King of Denmark Christian IX, 1818

Dionysios Solomos (Greek: Διονύσιος Σολωμός, 8 April 1798 - 9 February 1857) was a Greek poet from Zakynthos. He is best known for writing the Hymn to Liberty (Greek: Ὕμνος εἰς τὴν Ἐλευθερίαν, Ýmnos eis tīn Eleutherían), of which the first two stanzas on music by Nikolaos Mantzaros became the Greek national anthem in 1865. He was the central figure of the Heptanese School of poetry, and is considered the national poet of Greece - not only because he wrote the national anthem, but also because he contributed to the preservation of earlier poetic tradition and highlighted its usefulness to modern literature. Other notable poems include Ο Κρητικός (Τhe Cretan), Ελεύθεροι Πολιορκημένοι (The Free Besieged) and others. A characteristic of his work is that no poem except the Hymn to Liberty was completed, and almost nothing was published during his lifetime.

Born in 1798, Dionysios Solomos was the illegitimate child of a wealthy count, Nikolaos Solomos, and his housekeeper, Angeliki Nikli. Nikolaos Solomos was of Cretan origin; his family were Cretan refugees who settled on Zakynthos in 1670 after Crete's conquest by the Ottoman Empire in 1699. The Italian version of the family name is recorded as: Salamon, Salomon, Solomon, Salomone. It is possible that his mother Angeliki Nikli came from the region of Mani. Count Nikolaos Solomos was legally married to Marnetta Kakni, who died in 1802. From that marriage, he had two children: Roberto and Elena. Since 1796, Nikolaos Solomos had a parallel relationship with his housekeeper Angeliki Nikli, who gave birth to one more son apart from Dionysios, Dimitrios (born in 1801). His father married Dionysios' mother a day before he died on 27 February 1807, making the young Dionysios a legitimate and co-heir of the estate with his half-brother. The poet spent his childhood years on Zakynthos until 1808, under the supervision of his tutor abbey Santo Rossi who was an Italian refugee. After his father's death, count Dionysios Messalas gained Solomos' custody, whereas his mother married Manolis Leontarakis in 15 August 1807. In 1808, Messalas sent Solomos to Italy in order to study law, in line with the Ionian islands' tradition among nobility but possibly also because of Dionysios' mother's new marriage.

Solomos went to Italy with his tutor who returned to his homeland Cremona. Initially he was enrolled at the Lyceum of St. Catherine in Venice, but he had adjustment difficulties because of the school's strict discipline. For that reason, Rossi took Solomos with him to Cremona, where he finished his high-school studies in 1815. In November 1815, Solomos was enrolled at Pavia's University's Faculty of Law, from which he graduated in 1817. Given the interest the young poet showed in the flourishing Italian literature and being a perfect speaker of Italian, he started writing poems in Italian. One of the most important first poems written in Italian during that period of time was the Ode per la prima messa (Ode to the first mass) and La distruzione di Gerusalemme (The destruction of Jerusalem). In the meantime, he acquainted himself with famous Italian poets and novelists (possibly Manzoni, Vincenzo Monti etc); Ugo Foscolo from Zakynthos was among his friends. As a result, he was easily accepted in the Italian literary circles and evolved into a revered poet of the Italian language.

After 10 years of studies Solomos returned to Zakynthos in 1818 with a solid background in literature. On Zakynthos, which at that time was well-known for its flourishing literary culture, the poet acquainted himself with people interested in literature. Antonios Matesis (the author of Vasilikos), Georgios Tertsetis, Dionysios Tagiapieras (doctor, supporter of the dimotiki and also a friend of Vilaras) and Nikolaos Lountzis were some of Solomos' best known friends. They used to gather in each other's homes and amused themselves by making up poems. They frequently satirized a Zakynthian doctor, Roidis (Solomos' satirical poems referring to the doctor are The doctors' council, the New Year's Day and The Gallows). They also liked to improvise poems with given rhyme and topic. His improvised Italian poems during that period of time were published in 1822, under the title Rime Improvvisate.

Along with the Italian poems, Solomos made his first attempts to write in Greek. This was a difficult task for the young poet, since his education was classic and Italian but also because there did not exist many notorious poetic works written in the demotic dialect that could have served as models. However, the fact that his education in Greek was minimal kept him free of any scholarly influences, that might have led him to write in katharevousa, a "purist" language heavily influenced by ancient Greek. Instead he wrote in the language of the common people of his native island. In order to ameliorate his language skills, he started studying methodically demotic songs, the works of pre-solomian poets (προσολωμικοί ποιητές) and popular and Cretan literature that at that time constituted the best samples of the use of the demotic dialect in modern Greek literature. The result was the first extensive body of literature written in the demotic dialect, a move whose influence on subsequent writers cannot be overstated. Poems dating to that period of time are I Xanthoula-The little blond, I Agnoristi-The Unrecognizable, Ta dyo aderfia-The two brothers and I trelli mana-The crazy mother.

Solomos' encounter with Spyridon Trikoupis in 1822 was a turning-point in his Greek writing. When Trikoupis visited Zakynthos in 1822, invited by lord Guilford, Solomos' fame on the island was already widespread and Trikoupis wished to meet him. During their second meeting, Solomos read to him the Ode to the first mass. Impressed by Solomos' poetic skills, Trikoupis stated:

Your poetic aptitude reserves for you a selected place on the Italian Parnassos. But the first places there are already taken. The Greek Parnassos does not yet have its Dante".

Solomos explained to Trikoupis that his Greek was not fluent, and Trikoupis helped him in his studies of Christopoulos' poems.

The first important turn-point in the Greek works of Solomos was the Hymn to Liberty that was completed in May 1823-a poem inspired by the Greek revolution 1821. The poem was at first published in 1824 in the occupied Mesologgi and afterwards in Paris in

1825 translated into French and later on in other languages too. This

resulted in the poet's fame proliferation outside the Greek borders.

Thanks to this poem, Solomos was revered until his death, since the

rest of his work was only known to his small circle of admirers and his

"students". The Hymn to Liberty inaugurated

a new phase in the poet's literary work: this is the time when the poet

has finally managed to master the language and is experimenting himself

with more complex forms, opening up to new kinds of inspirations and

easily leaving aside improvisation. This period resulted in the Odi eis to thanato tou Lordou Byron-Ode to the death of Lord Byron, a poem having many things in common with the Hymn but also many weaknesses, I Katastrofi ton Psaron-Psara's Destruction, O Dialogos -The Dialogue (referring to the language) and I Gynaika tis Zakynthos -The Woman from Zakynthos.

It is alleged that Solomos could hear the canons firing from Zakynthos

during the Greek War of Independence, which inspired him to write his

most famous works.

After frictions and economic disputes with his brother Dimitrios concerning legacy matters, Solomos moved to Corfu, the most important spiritual center of the Ionian islands in those years. However, Dionysios did not leave Zakynthos solely because of his family problems; Solomos had been planning to visit the island since 1825. Corfu would offer him not only a more stimulating environment but also the vital isolation for his solitary and bizarre character. Corfu was the perfect place for contemplation and writing poetry, in line with Solomos' noble ideas about Art. That explains the fact that his happiest years were the first years he spent on Corfu. It was during this period of time that he took up studying German romantic philosophy and poetry (Hegel, Schlegel, Schiller, Goethe). Since he did not know German, he read Italian translations by his friend Nikolaos Lountzis. In the mean time, he continued to work on The Woman of Zakynthos and Lambros that he had started in 1826.

Between 1833 and 1838, having restored the relations with his brother, Solomos' life was perturbed by a series of trials where his half-brother (from his mother's side) Ioannis Leontarakis was claiming part of their father's legacy, arguing that he was also the legal child of count Nikolaos Solomos, since his mother was pregnant before the father's death. Even though the outcome of the trial was favorable to both the poet and his brother, the dispute led to Solomos' alienation from his mother (his feelings were badly hurt because of his adoration towards his mother) and his withdrawal from publicity. Even though the trial influenced the poet to such a point, it was not able to seize his poetical work. 1833 signifies the mature period of his poetical work, that resulted in the unfinished poems of O Kritikos-The Cretan (1833), Eleftheroi Poliorkimenoi-The Free Besieged (until 1845) and O Porfyras (1847), that are considered to be the best of his works. In the mean time, he was planning other works that either remained at the preparation stage or remained as fragments, such as Nikoforos Vryennios, Eis to thanato Aimilias Rodostamo -To the death of Emilia Rodostamo, To Fragiska Freizer and Carmen Seculare.

On Corfu, Solomos soon found himself at the admirers' and poets' center of attention, a group of well educated intellectuals with liberal and progressive ideas, a deep knowledge of art and with austere artistic pretensions. The most important people Solomos was acquainted to were Nikolaos Mantzaros, Ioannis and Spyridon Zampelios, Ermannos Lountzis, Niccolò Tommaseo, Andreas Moustoxydis, Petros Vrailas Armenis, Iakovos Polylas, Ioulios Typaldos, Andreas Laskaratos and Gerasimos Markoras. Polylas, Typaldos and Markoras were Solomos' students, constituting the circle referred to as the "solomian poets" (σολωμικοί ποιητές), which signifies Greek's poetry flourishing, several decades before the appearance of the New Athenian School, a second poetical renaissance inspired by Kostis Palamas.

After 1847, Solomos started writing in Italian once more. Most works from this period are half-finished poems and prose drafts that maybe the poet was planning to translate into Greek. Serious health problems made their appearance in 1851 and Solomos' character became even more temperamental. He alienated himself from friends such as Polylas (they came on terms with each other in 1854) and after his third stroke the poet did not leave his house. Solomos died in February 1857 from apoplexy. His fame had reached such heights so when the news about his death became known, everyone mourned. Corfu's theater closed down, the Ionian Parliament's sessions were suspended and mourning was declared. His remains were transferred to Zakynthos in 1865.