<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl, 1859

- Poet Dionysios Solomos, 1798

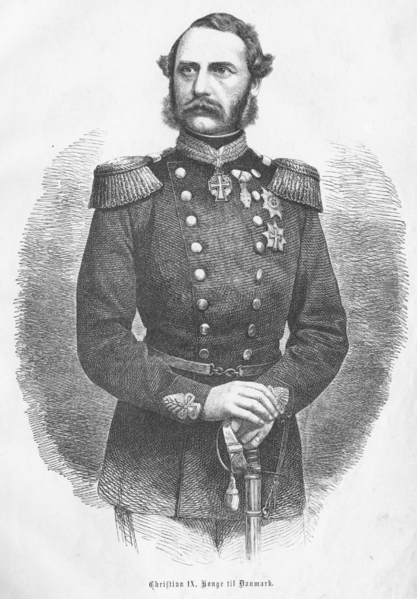

- King of Denmark Christian IX, 1818

Christian IX (8 April 1818 – 29 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 16 November 1863 to 29 January 1906. He became known as "the father-in-law of Europe", as his six children married into other royal houses; most current European monarchs are descended from him.

He was born in Gottorp, the fourth son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg and Louise Caroline, Princess of Hesse. Through his mother, Christian was a great-grandson of Frederick V of Denmark, great-great-grandson of George II of Great Britain and descendant of several other monarchs, but had no direct claim to any European throne. Through his father, Christian was a member of a junior male branch of the House of Oldenburgand a prince of the Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg line, a junior branch of the family which had ruled Denmark for centuries (he was a direct male-line descendant of King Christian III of Denmark) and was (albeit a junior) agnatic descendant of Helwig of Schauenburg (countess of Oldenburg), mother of King Christian I of Denmark, who was the "Semi-Salic" heiress of her brother Adolf of Schauenburg, last Schauenburg duke of Schleswig and count of Holstein. As such, Christian was eligible to succeed in the twin duchies of Schleswig-Holstein, but not first in the line.

He grew up in Denmark and was educated in the Military Academy of Copenhagen. As a young man, he unsuccessfully sought the hand of his third cousin Queen Victoria in marriage. At the Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen on 26 May 1842, he married Louise of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), a niece of Christian VIII. In 1847, under the blessing from the great powers of Europe, he was chosen as heir presumptive after the extinction of the most senior line to the Danish throne by Christian VIII, as the future Frederick VII seemed incapable of fathering children. A justification for this choice of heir was Christian's wife Louise of Hesse-Kassel. (As a great-niece of Christian VII, she was a closer heir to the throne than her husband.)

Christian succeeded upon his death Frederick VII to the throne on 15 November 1863. Denmark was immediately plunged into a crisis over the possession and status of Schleswig and Holstein, two provinces to Denmark's south. Under pressure, Christian signed the November Constitution, a treaty that made Schleswig part of Denmark. This resulted in a brief war between Denmark and a Prussian/Austrian alliance in 1864. This Second war of Schleswig's outcome was unfavorable to Denmark and led to the incorporation of Schleswig into Prussia in 1865. Holstein was likewise incorporated into Prussia in 1865, following further conflict between Austria and Prussia.

Frederick's

childlessness had presented a thorny dilemma and the question of

succession to the Danish throne proved problematic. Denmark's adherence

to the Salic Law and a burgeoning nationalism within the German-speaking parts of Schleswig-Holstein hindered

all hopes of a peaceful solution. Proposed resolutions to keep the two

Duchies together and as a part of Denmark proved unsatisfactory to both

Danish and German interests. While Denmark had adopted the Salic Law,

this only affected the descendants of Frederick III of Denmark, who was the first hereditary monarch of Denmark (before him, the kingdom was officially elective). Agnatic descent from

Frederick III ended when Frederick VII died. At that point, the law of

succession promulgated by Frederick III provided for a Semi-Salic succession.

There were however several ways to interpret to whom the crown could

pass, since the provision was not entirely clear as to whether a

claimant to the throne could be the closest female relative or not. As

the nations of Europe looked on, the numerous descendants of Helwig of

Schauenburg began to vie for the Danish throne. Frederick VII belonged

to the senior branch of Helwig's descendants. In 1863, Frederick, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg (1829–1880) (the future father-in-law of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany), proclaimed himself Frederick VIII of Schleswig-Holstein. Frederick von Augustenburg became the symbol of the nationalist German independence-movement in Schleswig-Holstein, after his father (in exchange for money) renounced his claims as first in line to inherit the twin-duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Following the London protocol of 8 May 1852, which concluded the First war of Schleswig and

given his father's renunciation, Frederick was deemed ineligible to

inherit. The closest female relatives of Frederick VII were his

paternal aunt, Louise,

who had married a scion of the cadet branch of the House of Hesse, and

her daughters. However, they were not agnatic descendants of the royal

family and thus not eligible to succeed in Schleswig-Holstein. The dynastic female heiress reckoned according to the original law of primogeniture of Frederick III was Caroline of Denmark (1793–1881), the childless eldest daughter of the late king Frederick VI. Along with another childless daughter Wilhelmine of Denmark (1808–1891),

Duchess of Glücksburg, and sister-in-law of Christian IX, the next

heir was Louise, sister of Frederick VI, who had married the Duke of

Augustenburg. The chief heir to that line was the selfsame Frederick of Augustenborg, but his turn would have come only after the death of two childless princesses who were very much alive in 1863. The

House of Glücksburg also held a significant interest in the

succession to the throne. A more junior branch of the royal clan, they

were also heirs of Frederick III, through the daughter of King Frederick V of Denmark.

Lastly, there was yet a more junior agnatic branch that was eligible to

succeed in Schleswig-Holstein. There was Christian himself and his

three older brothers, the eldest of whom, Karl, was childless, but the

others had produced children, and male children at that. Prince

Christian had been a foster "grandson" of the 'grandchildless' royal

couple Frederick VI and his queen consort Marie (Marie Sophie

Friederike of Hesse). Familiar with the royal court and the traditions

of the recent monarchs, their young ward, Prince Christian was

great-nephew of queen Marie, and descendant of a first cousin of

Frederick VI. He was brought up as Danish, having lived in

Danish-speaking lands of the royal dynasty, and had not become a German

nationalist which made him a relatively good candidate from the Danish

point of view. As junior agnatic descendant, he was eligible to inherit

Schleswig-Holstein, but was not the first in line. As descendant of

Frederick III, he was eligible to succeed in Denmark, although here

too, he was not first in line. In 1842, Christian married Princess Louise of Hesse,

daughter of the closest female relative of Frederick VII. Louise's

father and brother, both princes of Hesse, and elder sister too,

renounced their rights in favor of Louise and her husband. Prince

Christian's wife was now the closest female heiress of Frederick VII. In

1852, the thorny question of Denmark's succession was resolved by

legislation through which Christian was chosen to succeed Frederick VII

as the country's next reigning monarch. Christian IX was the 1,007th Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Spain in 1864 and the 744th Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1865. When Frederick died in 1863, Christian assumed the throne as Christian IX. In November 1863 Frederick of Augustenburg claimed the twin-duchies in succession after King Frederick VII of Denmark, who also was the Duke of Schleswig and Holstein, and who had died without a male heir. In 1864, Prussia and Austria initiated the Second war of Schleswig which eventually led to the Danish loss of both South Jutland and Holstein. Christian and Louise gave birth to six remarkably successful children: Crown Prince Frederick of Denmark, later Frederick VIII of Denmark (3 June 1843 – 14 May 1912). Married Princess Lovisa of Sweden. Princess Alexandra of Denmark, later the Queen consort of Edward VII of the United Kingdom (1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925). Prince Vilhelm (24 December 1845 – 18 March 1913), later King George I of Greece. Married Olga Konstantinovna, Grand Duchess of Russia. Princess Dagmar of Denmark, later the consort of Tsar Alexander III of Russia (26 November 1847 – 13 October 1928). Princess Thyra of Denmark, later consort of Ernst August of Hanover, 3rd Duke of Cumberland (29 September 1853 – 26 February 1933). Prince Valdemar of Denmark, (27 October 1858 – 14 January 1939). Married Princess Marie of Orléans-Chartres (1865–1909). Four of his children sat on the thrones (either as monarchs or as a consort) of Denmark, the United Kingdom, Russia and Greece.

A fifth, daughter Thyra, would have become Queen of Hanover, had her

husband's throne not been abolished before his reign began. The great

dynastical success of the six children was to a great extent not the

favor of Christian IX himself, but due to Christian's wife Louise of Hesse-Kassel dynastical ambitions. Some have compared her dynastical capabilities with those of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. Christian's grandsons included Nicholas II of Russia, Constantine I of Greece, George V of the United Kingdom, Christian X of Denmark and Haakon VII of Norway. He was, in the last years of his life, named Europe's "father-in-law". Today, most of Europe's reigning and ex-reigning royal families are direct descendants of Christian IX. Christian died peacefully of old age at 87 at the Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen and was buried in Roskilde Cathedral. The

defeat of 1864 cast a shadow of Christian IX's rule for many years also

because his attitude to the Danish case—probably without reason—was

claimed to be half-hearted. This unpopularity was worsened, as he

sought, unsuccessfully, to prevent the spread of democracy throughout

Denmark by supporting the authoritarian and conservative prime minister Estrup whose rule 1875–94 was by many seen as a semi-dictatorship. However, he signed a treaty in 1874 which allowed Iceland,

then a Danish possession, to have its own constitution, albeit one that

still had Denmark ruling Iceland. In 1901 he reluctantly asked Johan Henrik Deuntzer to form a government and this resulted in the formation of the Cabinet of Deuntzer. The cabinet consisted of members of the Venstre Reform Party and was the first Danish government not to include the conservative party Højre, even though Højre never had a majority of the seats in the Folketing. This was the beginning of the Danish tradition of parliamentarism and clearly bettered his reputation for his last years. Another

reform occurred in 1866, when the Danish constitution was revised so

that Denmark's upper chamber would have more power than the lower.

Social security also took a few steps forward during his reign. Old age

pensions were introduced in 1891 and unemployment and family benefits

were introduced in 1892.