<Back to Index>

- Nuclear Chemist Glenn Theodore Seaborg, 1912

- Dramatist José Echegaray y Eizaguirre, 1832

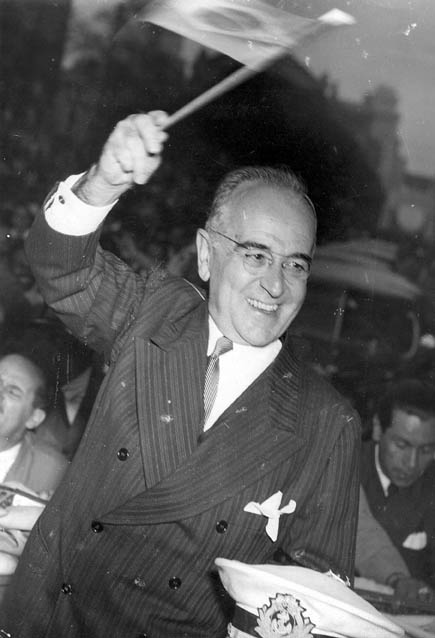

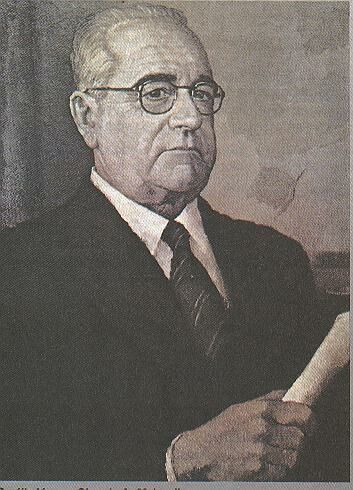

- President of Brazil Getúlio Dornelles Vargas, 1882

Getúlio Dornelles Vargas (April 19, 1882 – August 24, 1954) served as president of Brazil from 1930 to 1945 and from 1951 until his suicide in 1954. Vargas led Brazil for 15 years, being the president with more years of office. Vargas also won the nickname "The father of the poor" because of his worker's policy.

Vargas was born in São Borja, Rio Grande do Sul, on April 19, 1882, to Manuel do Nascimento Vargas and Cândida Dornelles Vargas. His father had origins in São Paulo, while his mother was descended from a wealthy family of Azorean Portuguese descent. The son of a traditional family of "gaúchos", he embarked on a military career at first, then turned to the study of law. Entering Republican politics, he was elected to the Rio Grande do Sul state legislature and later to the federal Chamber of Deputies, where he became the floor leader for his state's delegation in Congress. He served briefly as Secretary of the Treasury under President Washington Luís from which post he resigned to enter the gubernatorial race in his home state. Once elected Governor of Rio Grande do Sul, he became a leading figure in the opposition, urging the end of electoral corruption through the adoption of the universal and secret ballot.

He

and his wife Darcy Lima Sarmanho, whom he married in March 1911, had

five children. According to the legend, the real Love of Vargas was not

his wife but Aimee de Sa Sattomajor, later Aimee de Heeren, recognized

by the International Fashion press as one of the World´s most

glamorous and beautiful women. The

relation was kept as a Brazilian state secret, but Vargas mentioned her

in his diary which was published after the death of his wife. Aimee de

Herren, later living between France and the US and admired by other

famous States People like the four Kennedy brothers, Joseph, JFK,

Robert and Edward, never confirmed nor denied the rumor. Between

the two World Wars, Brazil was a rapidly industrializing nation

popularly regarded as "the sleeping giant of the Americas" and a

potential world power. However, the oligarchic and decentralized

confederation of the Old Republic, dominated by landed interests, in effect, showed little concern for promoting industrialization, urbanization, and other broad interests of the new middle class. Bourgeois

and military discontent, heightened by the Great Depression's impact on

the Brazilian economy, led to a bloodless coup d'état on October 24, 1930 that ousted President Washington Luís and his heir-apparent Júlio Prestes.

Júlio Prestes at this point was the newly elected president.

Regional leaderships dissatisfied with the state of São Paulo's

political dominance gathered around the states that formed the so

called Liberal Alliance - Minas Gerais, Paraíba and Rio Grande

do Sul - that had backed the defeated candidate Vargas. The whole

process was questioned and denounced as fraudulent by both sides, as it

usually was back in the period known as the Old Republic (1889-1930).

The military, traditionally active in Brazilian politics, deposed

Washington Luís and installed the runner-up Vargas as

"provisional president." Vargas

was a wealthy pro-industrial nationalist and anti-communist who favored

capitalist development and liberal reforms. Opposition to him would

later be radicalized in the 1932 movement that was initially aimed at

the establishment of a new constitution, but was in truth an oligarchic

attempt at façade democracy. Vargas's Liberal Alliance drew

support from wide ranges of Brazil's burgeoning urban middle class and

a group of tenentes, who had grown frustrated to some extent with the politics of coronelismo and café com leite. The

revolt was beaten, but a new constitution came out in 1934. After that,

Vargas seized absolute power and controlled dissidents through press

and mail censorship, stripping the country of most of the

trappings through which it eventually hoped to become the

democracy that he had purported to defend in 1930. His tenuous

coalition also lacked a coherent program, being committed to a broad

vision of modernization, but little more specific. Vargas' long career

(including his eventual dictatorship, modelled, surprisingly

considering the liberal roots of his regime, almost along the lines of

European Fascism),

may be explained by his balancing the conflicting ideological

constituencies, regionalism and economic interests within the vast,

diverse and socio-economically varied nation. As

a candidate in 1930 Vargas utilized populist rhetoric to promote

bourgeois concerns, thus opposing the primacy — but not the legitimacy — of the Paulista coffee

oligarchy and the land elites, who had little interest in protecting

and promoting industry and modernization. Vargas during this period

sought to bring Brazil out of the Great Depression through orthodox policies, and was capable of doing that with relative ease. Like Franklin Roosevelt in

the U.S., his first steps focused on economic stimulus. A state

interventionist policy utilizing tax breaks, lowered duties, and import

quotas allowed Vargas to expand the domestic industrial base. Vargas

linked his pro-industrial policies to nationalism, advocating heavy

tariffs to "perfect our manufacturers to the point where it will become

unpatriotic to feed or clothe ourselves with imported goods." In his

early years, Vargas also relied on the support of the tenentes,

junior military officers, who had long been active against the ruling

coffee oligarchy, staging their own failed revolt in 1922. Vargas also

quelled a Paulista female workers' strike by co-opting much of their

platform and requiring their "factory commissions" to use government

mediation in the future. Vargas, reflecting the influence of the tenentes, even advocated a program of social welfare and reform similar to the New Deal. The parallels between Vargas and the European police states began to appear by 1934, when a new constitution was enacted with some direct almost-fascist influences. Brazil's

1934 constitution, passed on July 16, contained provisions that

resembled Italian corporatism, which had the enthusiastic support of

the pro-fascist wing of the disparate tenente movement

and industrialists, who were attracted to Mussolini's co-optation of

unions through state-run, sham syndicates. As in Italy, and later Spain and Germany,

Fascist-style programs would serve two important aims, stimulating

industrial growth and suppressing the communist influence in the

country. Its stated purpose, however, was uniting all classes in mutual

interests. The constitution established a new Chamber of Deputies that

placed government authority over the private economy, which established

a system of state-guided capitalism aimed at industrialization and

reducing foreign dependency. After

1934, the regime designated corporate representatives according to

class and profession, but maintained private ownership of

Brazilian-owned business. Based on increased labor rights and social

investment, Brazilian corporatism, was actually a strategy to increase

industrial output utilizing a strong nationalist appeal. Vargas, and

later Juan Perón in neighboring Argentina,

another quasi-fascist, kind of emulated some Mussolini's strategy of

mediating class disputes and co-opting workers' demands under the

banner of nationalism. Under the increase of workers' rights also, he

greatly expanded labor regulations with the consent of industry,

pacified by strong industrial growth. The new constitution, drafted by

Vargas allies, expanded social programs and set a minimum wage but also

placed stringent limits on union organizing and "unauthorized" strikes. Beyond

corporatism, the 1934 constitution also heightened efforts to reduce

provincial autonomy in the traditionally devolved, sprawling nation.

Centralization allowed Vargas to curb the oligarchic power of the

land paulista elites, who obstructed modernization through

the regionalism, machine politics, and façade, corrupt democracy

of the Old Republic. Threatened by pro-Communist elements in labor

critical of the rural latifundios, Vargas reined in his shaky alliance with labor and began formally co-opting the less intimidating fascist movement. As

he moved to the right after 1934, his ideological character and

association with a global ideological orbit, however, remained

ambiguous — reminiscent of the early phases of leftist leaders Fidel Castro and Daniel Ortega. To fill this ideological void and promote his new rightist policies, Vargas began moving against the tenentes while encouraging the growth of fascist paramilitaries. "Integralism", founded and led by Plínio Salgado,

who adopted Fascist and Nazi symbolism and salutes, offered Vargas a

new political base. A green-shirted paramilitary organization directly

financed by Mussolini and Hitler, Integralism's propaganda campaigns were borrowed directly from Nazi models — excoriations of Marxism, liberalism and Jews, that espoused fanatical nationalism and "Christian virtues". Vargas tolerated this rise of anti-Semitism,

even not being anti-semitic at all, and may have acted upon the

Integralists’ popularization of anti-Semitism. One example is the

deportation of the pregnant, German-born Jewish wife of Luís Carlos Prestes, Olga Benário Prestes,

who was not only a spy working for the USSR and an illegal

immigrant, but also tried to install a communist government in Brazil

through the Intentona Comunista, to Nazi Germany, where she would die

in a concentration camp. Vargas

forced Congress to respond to the growth of the Aliança Nacional

Libertadora (ANL), a leftist coalition led by the Communist Party and Luís Carlos Prestes. A revolutionary forerunner of Che Guevara,

Prestes led the legendary but futile "Long March" through the rural

Brazilian interior following his participation in the failed 1922 tenente rebellion

against the coffee oligarchs. This experience, however, left Prestes

and some of his followers sceptical of armed conflict. Nonetheless,

Congress branded all leftist opposition as "subversive" under a March

1935 National Security Act that allowed the President to ban the ANL,

which was forced — reluctantly — to begin another armed insurrection in

November. The authoritarian regime responded by violently crushing the

Communist movement through state terror like that of the US. Although

"the father of the poor" expanded the electorate, granted women's

suffrage, enacted social security reforms, legalized labor unions as a

populist, Vargas also whittled down the autonomy of labor and crushed a

series of "social banditry" violence revolts known as the cangaço. Vargas utilized fears over communism to justify personal dictatorship. Although autoritarian, the "Estado Novo"

dictatorship cannot be considered a fascist regime, for Vargas had no

specific party, and also, the Vargas dictatorship did not make use of the

violent excess of European fascism. The Vargas dictatorship finally

materialized in 1937, when Vargas was forced to step down as president

by January 1938 because his own 1934 constitution prohibited the

president from succeeding himself. On 29 September 1937, Gen. Dutra,

his rightist collaborator, presented "the Cohen Plan" that established

a detailed plan for a Communist revolution. The Cohen Plan was a mere

forgery concocted by the Integralists, but Dutra publicly demanded a state of siege.

On November 10, Vargas, ruling by decree, then made a broadcast in

which he stated his plans to assume dictatorial powers under a new

constitution, thereby curtailing presidential elections (his ultimate

objective) and dissolving congress. Vargas, consolidated dictatorial

powers by acting within the established political system, not in a

single coup d'état or revolution. Under the Estado Novo, Vargas abolished political parties, imposed censorship,

established a centralized police force, and filled prisons with

political dissidents, while evoking a sense of nationalism that

transcended class and bound the masses to the state. He ended up

repressing the "Integralism" as well, once the communists were already defeated, since the Integralists wished for a total Nazi-fascist dictatorship. Vargas

intelligently used ambiguous policy towards Axis and Allied

orbits. Brazil appeared to be entering the Axis orbit — even before the

1937 declaration of Estado Novo. Between 1933 and 1938 Germany became

the principal market for Brazilian cotton, and its second largest importer of Brazilian coffee and cacao. The German Bank for South America even established three hundred branches in Vargas' Brazil. Using periodic overtures to the Axis Powers, along with rapid increase in civilian and military trade between Brazil and Nazi Germany gave US officials reason to wonder about Vargas' international alignment. Then the US started to reach out to Brazilians, with the "Good Neighbor Policy". Carmen Miranda became a Hollywood star and even Donald Duck "visited" Brazil, to bring Brazil into

the war. US also granted a huge amount of money to Vargas, which he

would use in industrialization of the country. Vargas eventually sided

with the Allies, declared war on the Axis.

The shrewd, low-key, and reasoned pragmatist sided with the antifascist

Allies after a period of ambiguity for economic reasons, since the

Allies were more viable trading partners and helped with money, and

liberalized his regime because of complications arising from this

alliance. In siding with the Allies, one agreement that Vargas made was

to help the Allies with rubber production in order to receive loans and

credit from the US. This

siding with the antifascist Allies created a paradox at home not

unnoticed by Brazil's middle class (of a fascist-like regime joining

the antifascist Allies) that Salazar and Franco avoided

by maintaining nominal neutrality, allowing them to avoid both

antifascist sentiment at home arising from siding with the Allies or

annihilation by the Allies. Vargas

thus astutely responded to the newly liberal sentiments of a middle

class that was no longer fearful of disorder and proletarian discontent

by moving away from repression — promising "a new postwar era of

liberty" that included amnesty for political prisoners, presidential

elections, and the legalization of opposition parties — including the

moderated and irreparably weakened Communist Party. Such political liberalization contributed to the downfall of the

Estado Novo, being substantial enough to provoke a 1945 military coup

d'état led by Dutra and Monteiro, who were alarmed with Vargas' growing ties with labor and the working classes. Despite

the passage of many labor laws that significantly improved the lives of

laborers (such as paid vacation, minimum wage, and maternity leave),

there were still many shortcomings in the enforcement and

implementation of labor legislation. While it was impossible for the minimum wage laws to be evaded by large businesses or in large towns, the minimum rural salary of 1943 was, in many cases, simply not abided by employers. In fact, many social policies never extended to rural areas. While

each state varied, social legislation was enforced less by the

government and more by the good will of employers and officials in the

remote regions of Brazil. Vargas'

legislation did more for the industrial workers than for the more

numerous agricultural workers, despite the fact that a few industrial

workers joined the unions that the government encouraged. The state-run social security system was inefficient and the Institute for Retirement and Social Welfare produced few results. The popular backlash due to these shortcomings was evidenced by the rising popularity of the National Liberation Alliance. When

he left Estado Novo's presidency, the economic surplus of Brazil was

high and the industry was growing. After 4 years, however, pro-US Gaspar

Dutra wasted huge quantities of money protecting foreign

industry (mostly US) and stopping with the ideas of nationalism and

modernization of the country. Vargas returned to politics in 1951 and

through a free and secret ballot was re-elected President of the

Republic. Hampered by the economic crisis created by pro-US Dutra,

Vargas pursued a nationalist policy; turning to the country's natural

resources and away from foreign dependency. As part of this policy, he

founded Petrobrás (Brazilian oil). His political adversaries initiated a crisis which culminated in the "Rua Tonelero", where Major Rubens Vaz was killed during an attempt on the life of Vargas' main adversary, Carlos Lacerda.

Lieutenant Gregório Fortunato, chief of Vargas' personal guard,

was accused of masterminding the assassination attempt. This aroused a

reaction in the military against Vargas and the generals demanded his

resignation. In a last ditch effort Vargas called a special cabinet

meeting on the eve of August 24, but rumors spread that the armed

forces officers were implacable. Feeling the situation beyond his control, Vargas shot himself in the chest on August 24, 1954 in the Catete Palace. He wrote a letter to the Brazilian people known as his "carta testamento." The famous last lines read, "Serenely, I take my first step on the road to eternity and I leave life to enter history." On

exhibit in the Palace is his nightshirt with a bullet hole in the

breast. The popular commotion that his suicide caused was so huge, that

it destroyed the ambitions of his enemies for many years, among them

rightists anti-nationalists and pro-US. Getúlio Dornelles Vargas is interred in his native São Borja, in Rio Grande do Sul.