<Back to Index>

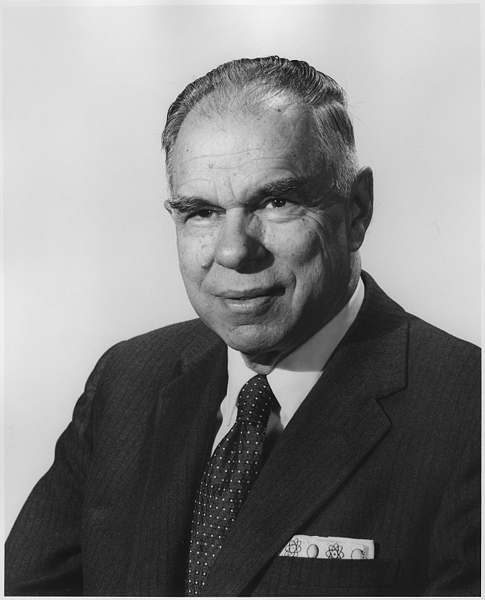

- Nuclear Chemist Glenn Theodore Seaborg, 1912

- Dramatist José Echegaray y Eizaguirre, 1832

- President of Brazil Getúlio Dornelles Vargas, 1882

Glenn Theodore Seaborg (Swedish: Glenn Teodor Sjöberg; April 19, 1912 – February 25, 1999) was an American scientist who won the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for "discoveries in the chemistry of the transuranium elements," contributed to the discovery and isolation of ten elements, developed the actinide concept, which led to the current arrangement of the actinoid series in the periodic table of the elements. He spent most of his career as an educator and research scientist at the University of California, Berkeley where he became the second Chancellor in its history and served as a University Professor. Seaborg advised ten presidents from Truman to Clinton on nuclear policy and was the chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission from 1961 to 1971 where he pushed for commercial nuclear energy and peaceful applications of nuclear science. Throughout his career, Seaborg worked for arms control. He was signator to the Franck Report and contributed to the achievement of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Seaborg was a well-known advocate of science education and federal funding for pure research. He was a key contributor to the report "A Nation at Risk" as a member of President Reagan's National Commission on Excellence in Education and was the principal author of the Seaborg Report on academic science issued in the closing days of the Eisenhower administration.

Seaborg was the principal or co-discoverer of ten elements: plutonium, americium, curium, berkelium, californium, einsteinium, fermium, mendelevium, nobelium and element 106, which was named seaborgium in

his honor while he was still living. He also developed more than 100

atomic isotopes, and is credited with important contributions to the

chemistry of plutonium, originally as part of the Manhattan Project where he developed the extraction process used to fuel the atomic bomb used on Nagasaki.

Early in his career, Seaborg was a pioneer in nuclear medicine and

developed numerous isotopes of elements with important applications in

the diagnosis and treatment of diseases, most notably iodine-131, which

is used in the treatment of thyroid disease. In addition to his

theoretical work in the development of the actinide concept which

placed the actinide series beneath the lanthanide series on the

periodic table, Seaborg proposed the placement of super-heavy elements

in the transactinide and superactinide series. After sharing the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Edwin McMillan, he received approximately 50 honorary doctorates and numerous other awards and honors. The list of things named after Seaborg ranges from his atomic element to an asteroid. Seaborg was a prolific author, penning more than 50 books and 500 journal articles, often in collaboration with others. He received so many awards and honors that he was once listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the person with the longest entry in Who's Who in America. Of Swedish ancestry, Seaborg was born in Negaunee, Michigan,

the son of Herman Theodore (Ted) and Selma Olivia Erickson Seaborg. He

had one sister, Jeanette. When Glenn Seaborg was a boy, the family

moved to the Seaborg Home in a subdivision called Home Gardens, that was later annexed to the City of South Gate, California, a suburb of Los Angeles. He

kept a daily journal from 1927 until he suffered a stroke in 1998. As a

youth, Seaborg was both a devoted sports fan and an avid movie buff.

His mother encouraged him to become a book-keeper as she felt his

literary interests were impractical. He did not take an interest in

science until his junior year when he was inspired by Dwight Logan

Reid, a chemistry and physics teacher at David Starr Jordan High School in Watts. He graduated from Jordan in 1929 at the top of his class and received a bachelor's degree in chemistry at the University of California, Los Angeles in 1934. While at UCLA, he was invited by his German professor to meet Albert Einstein,

an experience that had a profound impact on Seaborg and served as a

model of graciousness for his encounters with aspiring students in

later years. Seaborg worked his way through school as a stevedore (longshoreman), fruit packer and laboratory assistant. Seaborg took his Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1937 with a doctoral thesis on the inelastic scattering of neutrons in which he coined the term "nuclear spallation". He was a member of the professional chemistry fraternity Alpha Chi Sigma. As a graduate student in the 1930s Seaborg performed wet chemistry research for his advisor Gilbert Newton Lewis and published three papers with him on the theory of acids and bases. Seaborg then studied thoroughly the text Applied Radiochemistry by Otto Hahn, of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in

Berlin and it had a major impact on his developing interests as a

research scientist. For several years, Seaborg conducted important

research in artificial radioactivity using the Lawrence cyclotron at UC Berkeley. He was excited to learn from others that nuclear fission was possible—but also chagrined, as his own research might have led him to the same discovery. Seaborg also became expert in dealing with noted Berkeley physicist Robert Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer had a daunting reputation, and often answered a junior

man's question before it had even been stated. Often the question

answered was more profound than the one asked, but of little practical

help. Seaborg learned to state his questions to Oppenheimer quickly and

succinctly. Seaborg remained at the University of California, Berkeley for post-doctoral research. He followed Frederick Soddy's work investigating isotopes and contributed to the discovery of more than 100 isotopes of elements. Using one of Lawrence's advanced cyclotrons, John Livingood, Fred Fairbrother, and Seaborg created a new isotope of iron, iron-59 (Fe-59) in 1937. Iron-59 was useful in the studies of the hemoglobin in human blood. In 1938, Livingood and Seaborg collaborated (as they did for five years) to create an important isotope of iodine, iodine-131 (I-131) which is still used to treat thyroid disease. (Many

years later, it was credited with prolonging the life of Seaborg's

mother.) As a result of these and other contributions, Seaborg is

regarded as a pioneer in nuclear medicine and is one of its most

prolific discoverers of isotopes. In 1939 he became an instructor in chemistry at UC Berkeley, was promoted to assistant professor in 1941 and professor in 1945. UC Berkeley physicist Edwin McMillan had led a team that discovered element 93, neptunium in

1940. However in November 1940, McMillan was persuaded to leave

Berkeley temporarily to assist with urgent research needed to advance

radar technology. Since Seaborg and his colleagues had perfected

McMillan's oxidation-reduction technique for isolating neptunium, he

asked McMillan for permission to continue the research and search for

element 94. McMillan agreed to the collaboration. Seaborg

first reported alpha decay proportionate to only a fraction of the

element 93 under observation. The first hypothesis for this alpha

particle accumulation was contamination by uranium, which produces

alpha-decay particles. However, an analysis of alpha-decay particles

ruled out the hypothesis. Seaborg then postulated that a distinct

alpha-producing element was being formed from element 93. In February

1941, Seaborg and his collaborators produced plutonium-239 through the

bombardment of uranium. This experimental achievement changed the

course of human history in ways more profound than they could have ever

imagined: the production of plutonium-239 was successful. In their

experiments bombarding uranium with deuterons, they observed the

creation of neptunium, element 93. But it then underwent beta-decay,

forming a new element, plutonium, with 94 protons. Plutonium is fairly

stable, but undergoes alpha-decay, which explained the presence of

alpha particles coming from neptunium. Thus, on March 28, 1941, Dr. Seaborg, physicist Emilio Segre' and Berkeley chemist Joseph W. Kennedy were able to show that plutonium (then known only as element 94)

underwent fission with slow neutrons, an important distinction that was

crucial to the decisions made in directing Manhattan Project research.

In the same year in which he produced plutonium, 1941, he also

discovered that the isotope U235 undergoes fission under appropriate conditions. He therefore contributed to the

science enabling two different approaches to the development of nuclear weapons. In

addition to plutonium, he is credited as a lead discoverer of

americium, curium, and berkelium, and as a co-discoverer of

californium, einsteinium, fermium, mendelevium, nobelium and

seaborgium. He shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1951 with Edwin McMillan for

"their discoveries in the chemistry of the first transuranium

elements." He obtained patents on americium and curium, which were

developed in 1944 in Chicago at the wartime metallurgical laboratory

during the Manhattan project. His research contributions to all of the

other elements were conducted at the University of California, Berkeley. On April 19, 1942, Seaborg reached Chicago, and joined the chemistry group at the Metallurgical Laboratory of the Manhattan Project at the University of Chicago, where Enrico Fermi and his group would later convert U238 to plutonium in the world's first controlled nuclear chain reaction using a chain-reacting pile. Seaborg's role was to figure out how to extract the tiny bit of plutonium from the mass of uranium.

Plutonium-239 was isolated in visible amounts using a transmutation

reaction on August 20, 1942 and weighed on September 10, 1942 in

Seaborg's Chicago laboratory. He was responsible for the multi-stage

chemical process that separated, concentrated and isolated plutonium. This process was further developed at the Clinton Engineering Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and then entered full-scale production at the Hanford Engineer Works, in Richland, Washington. Seaborg's theoretical development of the actinide concept resulted in a redrawing of the Periodic Table of the Elements into its current configuration with the actinide series appearing below the lanthanide series. Seaborg developed the chemical elements americium and curium while

in Chicago. He managed to secure patents for both elements. His patent

on curium never proved commercially viable because of the element's

short half-life. Americium is commonly used in household smoke

detectors, however, and thus provided a good source of royalty income

to Seaborg in later years. Prior to the test of the first nuclear

weapon, Seaborg joined with several other leading scientists in a

written statement known as the Franck Report (secret

at the time but since published) calling on President Truman to conduct

a public demonstration of the atomic bomb witnessed by the Japanese

rather than engaging in a surprise attack. Truman instead proceeded to

drop two bombs, credited by most observers at the time with ending the

war, a uranium bomb on Hiroshima and a plutonium bomb on Nagasaki. After

the conclusion of World War II and the Manhattan Project, Seaborg was

eager to return to academic life and university research free from the

restrictions of wartime secrecy. In 1946, he added to his

responsibilities as a professor by heading the nuclear chemistry

research at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory operated by the

University of California on behalf of the United States Atomic Energy

Commission. Seaborg was named one of the "Ten Outstanding Young Men in

America" by the U.S. Junior Chamber of Commerce in 1947 (along with Richard Nixon and others). Seaborg was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in

1948. From 1954 to 1961 he served as associate director of the

radiation laboratory. He was appointed by President Truman to serve as

a member of the General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission, an assignment he retained until 1960. Seaborg served as chancellor at

University of California, Berkeley from 1958 to 1961. His term as

Chancellor came at a time of considerable controversy during the time

of the free speech movement. In October 1958, he announced that the

University had relaxed its prior prohibitions on political activity on

a test basis. Seaborg served on the Faculty Athletic Committee for several years and is the co-author of a book concerning the Pacific Coast Conference scandal and the founding of the Pac-10 (formerly

Pac-8), in which he played a role. Seaborg served on the President's

Science Advisory Commission during the Eisenhower administration, which

produced the report "Scientific Progress, the Universities, and the

Federal Government," also known as the "Seaborg Report," in November

1960. The Seaborg Report is credited with influencing the federal

policy towards academic science for the next eight years. In 1959, he

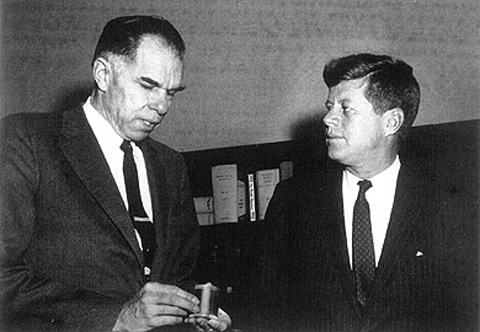

helped found the Berkeley Space Sciences Laboratory with UC president Clark Kerr. After appointment by President John F. Kennedy and confirmation by the United States Senate, Seaborg was chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)

from 1961 to 1971. His pending appointment by President Kennedy was

nearly derailed in late 1960 when members of the Kennedy transition

team learned that Seaborg had been listed in a U.S. News and World

Report article as a member of "Nixon's Brain Trust." Seaborg said that

as a lifetime Democrat he was baffled when the article appeared

associating him with Vice President Nixon, whom he considered a casual

acquaintance. While chairman of the AEC, Seaborg participated on the negotiating team for the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT).

Seaborg considered his contributions to the achievement of the LTBT as

his greatest accomplishment. Despite strict rules from the Soviets

about photography at the signing ceremony, Seaborg sneaked a tiny

camera past the Soviet guards to take a close-up photograph of Soviet

Premier Khrushchev as he signed the treaty. Seaborg enjoyed a close relationship with President Lyndon Johnson and influenced the administration to pursue the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Seaborg was called to the White House in the first week of the Nixon Administration in January 1969 to advise President Richard Nixon on his first diplomatic crisis involving the Soviets and nuclear testing. Seaborg clashed with Nixon presidential adviser John Ehrlichman over the treatment of a Jewish scientist whom the Nixon administration suspected of leaking nuclear secrets to Israel. Seaborg

published several books and journal articles during his tenure at the

Atomic Energy Commission. His predictions concerning development of

stable super-heavy elements are considered among his most important

theoretical contributions. Seaborg theorized the transactinide series and the superactinide series

of undiscovered synthetic elements. While most of these theoretical

future elements have extremely short half-lives and thus no expected

practical applications, Seaborg theorized an island of stability for isotopes of certain elements. When

Seaborg resigned as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission in 1971,

he had served longer than any other Kennedy appointee. Following

his service as Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, Seaborg

returned to UC Berkeley where he was awarded the position of University

Professor. At the time, there had been fewer University Professors at

UC Berkeley than Nobel prize winners. He also served as Chairman of the

Lawrence Hall of Science. Seaborg served as President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1972 and as President of the American Chemical Society in 1976. In 1976, when the Swedish king visited the United States, Seaborg played a major role in welcoming the Swedish Royal Family. In 1980, he transmuted several thousand atoms of bismuth into gold at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. His experimental technique, using nuclear physics, was able to remove protons and neutrons from

the bismuth atoms. Seaborg's technique would have been far too

expensive to enable routine manufacturing of gold, but his work is the

closest to the mythical Philosopher's Stone. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan appointed

Seaborg to serve on the National Commission on Excellence in Education.

Upon seeing the final draft report, Seaborg is credited with making

comments that it was far too weak and did not communicate the urgency

of the current crisis. He compared the crisis in education to the arms race,

and stated that we are "a nation at risk." These comments led to a new

introduction to the report and gave the report the famous title which

focused national attention on education as an issue germane to the

federal government. Seaborg lived most of his later life in Lafayette, California,

where he devoted himself to editing and publishing the journals that

documented both his early life and later career. He rallied a group of

scientists who criticized the science curriculum in the State of

California which he viewed as far too socially oriented and not nearly

focused enough on hard science. California Governor Pete Wilson

appointed Seaborg to head a committee that proposed sweeping changes to

California's science curriculum despite outcries from labor

organizations and others. On August 24, 1998, while in Boston to attend a meeting by the American Chemical Society, Seaborg suffered a stroke, which led to his death six months later on February 25, 1999 at his home in Lafayette. In 1942, Seaborg married Helen Griggs, the secretary of Ernest Lawrence. Under

wartime pressure, Seaborg had moved to Chicago while engaged to Griggs.

When Seaborg returned to accompany Griggs for the journey back to

Chicago, friends expected them to marry in Chicago. But, eager to be

married, Seaborg and Griggs impulsively got off the train in the town of Caliente, Nevada for

what they thought would be a quick wedding. When they asked for City

Hall, they found Caliente had none—they would have to travel 25 miles north to Pioche, the county seat.

With no car, this was no easy feat but, happily, one of Caliente's

newest deputy sheriffs turned out to be a recent graduate of the Cal

Berkeley chemistry department and was more than happy to do a favor for

Seaborg. The deputy sheriff arranged for the wedding couple to ride up

and back to Pioche in a mail truck. The witnesses at the Seaborg

wedding were a clerk and a janitor. Seaborg

was honored as Swedish-American of the Year in 1962 by the Vasa Order

of America. In 1991, the organization named "Local Lodge Glenn T.

Seaborg No. 719" in his honor during the Seaborg Honors ceremony at

which he appeared. This lodge maintains a scholarship fund in his name,

as does the unrelated Swedish-American Club of Los Angeles. Seaborg

kept a close bond to his Swedish origin. He visited Sweden every so

often and his family were members of the Swedish Pemer Genealogical Society,

a family association open for every descendant of the Pemer family, a

Swedish family with German origin, from which Seaborg was descended on

his mother's side. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1972. The element seaborgium was

named after Seaborg by Albert Ghiorso, Darleane C. Hoffman, and others,

who also credited Seaborg as a co-discoverer. It was so named while

Seaborg was still alive, which proved controversial. He influenced the naming of so many elements that with the announcement of seaborgium, it was noted in Discover magazine's review of the year in science that he could receive a letter addressed in chemical elements: seaborgium, lawrencium (for the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory where he worked), berkelium, californium, americium. While

it has been commonly stated that seaborgium is the only element to have

been named after a living person, this is not entirely accurate; both einsteinium and fermium were proposed as names of new elements discovered by Albert Ghiorso while Enrico Fermi and Albert Einstein were still living. The discovery of these elements and their names were kept secret under Cold War era

nuclear secrecy rules, however, and thus the names were not known by

the public or the broader scientific community until after the deaths

of Fermi and Einstein. Thus seaborgium is the only element to have been

publicly named after a living person.