<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Immanuel Kant, 1724

- Author Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein, 1766

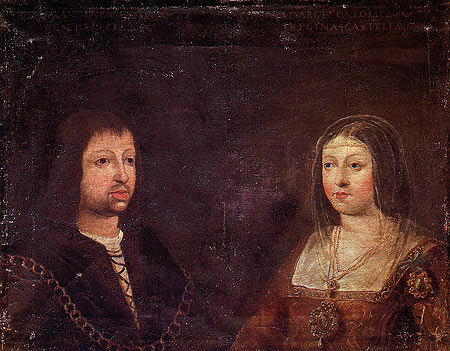

- Queen of Castilla y León Isabella I, 1451

Isabella I (22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504) was Queen of Castile and León. She and her husband Ferdinand II of Aragon brought stability to both kingdoms that became the basis for the unification of Spain. Later the two laid the foundation for the political unification of Spain under their grandson, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

The original Castilian version of her name was Ysabel (Isabel in modern spelling), which is etymologically the same as Elizabeth, but in Germanic countries she is nevertheless usually known by an Italian form of her name, Isabella. The official inscription on her tomb renders her names in Latin as "Helizabeth". Pope Alexander VI named Isabella and her husband the Catholic Monarchs for which reason she is often known as Isabel la Católica ("Isabella the Catholic" or "Elizabeth the Catholic") in Castilian. Isabella was born in the municipality of Madrigal de las Altas Torres. She was named after her mother Isabella of Portugal,

a name that was uncommon then in Castile. At the time of her birth, her

older half brother Henry was in line for the throne before her; Henry

was twenty-six at that time and was married but childless. Her brother Alfonso was born two years later and displaced her in the line of succession. When her father, John II, died in 1454, Henry became King Henry IV. She and her mother and brother then moved to Arévalo. It is here when her mother began to lose her sanity, a trait that would

haunt the Spanish monarchy and the royal houses of Europe that

descended from her. These were times of turmoil for Isabella; she also

suffered from shortage of money, a fact she would later weave into the

propaganda and mythos surrounding her rise to the throne. Even though

her father arranged in his will for his children to be financially well

taken care of, her brother Henry didn’t comply, either from ineptitude

or a desire to keep his siblings restricted. Later, Isabella reported

that during this time she found strength in scripture and books.

Isabella’s friendship with Saint Beatrix de Silva, whom she helped to found the order of the Conceptionists was

very influential in her early years. When the Queen was about to give

birth to the King’s daughter, Isabella and her brother were taken away

from their mother and brought to court in Segovia. Queen Joan was rumored to have had many lovers, one being Beltrán de la Cueva, and upon the birth of her daughter Joanna the

child was referred to as Joanna la Beltraneja, after her rumored

father. This name has stuck with her throughout history. As it has

never been firmly established whether or not Joanna was actually

Henry's daughter, and as the available contemporary sources are

unlikely to ever resolve this question for sure, it is entirely

possible that Joanna was in fact his legitimate heir. If so, it raises

interesting questions about the legitimacy of Isabella's tremendously

influential reign, as she and Ferdinand would then technically be

usurpers. The

noblemen who were anxious for power confronted the King, demanding that

his younger half brother Infante Alfonso be named his successor. They

even went as far as to ask Alfonso to seize the throne. The nobles, now

in control of Alfonso and claiming him to be the true heir, clashed with Henry's forces at the Battle of Olmedo in 1467. The battle was a draw. Henry agreed

to make Alfonso his heir, provided Alfonso would marry his daughter,

Joanna. A few days later, he changed his mind; Henry wanted to protect

the interest of his daughter and his name since by this time he was

being called Henry the Impotent. Soon after Alfonso was created Prince of Asturias,

the title given to the heir of Castile and Leon, he died, likely of the

plague; the nobles who had supported him suspected poisoning. As she

had been named in her brother's will as his successor, the nobles asked

Isabella to take his place as champion of the rebellion. However,

support for the rebels had begun to wane, and Isabella preferred a

negotiated settlement to continuing the war. She met with Henry and, at

Toros de Guisando, they reached a compromise: the war would stop, Henry

would name Isabella his heir instead of Joanna, and Isabella would not

marry without Henry's consent. Isabella's side came out with most of

what they desired, though they did not go so far as to officially

depose Henry: they were not powerful enough to do so, and Isabella did

not want to jeopardize the principle of fair inherited succession,

since it was upon this idea that she had based her argument for

legitimacy as heir. At the age of three Isabella was betrothed to Ferdinand the son of John II of Aragon (whose family was a cadet branch of the House of Trastámara). Nonetheless, Henry broke this agreement six years later so that she could marry Charles IV of Navarre,

another son of John II of Aragon. This marriage did not come about

because of John’s refusal. Other attempts were to marry Isabella to Alfonso V of Portugal.

In 1464 Henry managed to unite Afonso and Isabella in the Royal

Monastery of Santa Maria de Guadalupe, but she refused him because of

the great age difference between them (19 years). At

sixteen Isabella was betrothed to Pedro Giron, Maestre de Calatrava and

brother to the King’s favorite Don Juan Pacheco. Because of Juan’s

power over the King, this marriage was granted and Isabella made a plea

to God that marriage to this 43-year-old man would not come to pass.

Don Pedro died from a burst appendix while on his way to meet his

fiancée. The

King then tried to marry her to Afonso V of Portugal once more as part

of a scheme in which his daughter Juana would marry Afonso's son John II and

thus, after the death of the old king, John and Juana could inherit

Portugal and Castile. Isabella refused. After this failed attempt Henry

then tried to marry Isabella to Louis XI’s brother Charles, Duke of Berry.

Meanwhile John II of Aragon negotiated in secret with Isabella a

wedding to his son Ferdinand. Isabella felt that he was the best

candidate for her, but there was a problem: Ferdinand's and Isabella’s

grandfathers were brothers, so a papal dispensation was needed. The

pope was afraid of granting one from fear of bringing hostilities

towards Rome from the kingdoms of Castile, Portugal and France, all of

which had an interest in this matter. The fervent Isabella would not

agree to marriage until the dispensation was granted. With the help of

Rodrigo Borgia (later Alexander VI) Isabella and Ferdinand were presented with a supposed Papal Bull by Pius II in

their favor and Isabella agreed to the marriage. Isabella managed to

escape the court with the excuse of visiting her brother’s tomb in Ávila.

Ferdinand, on the other hand, crossed Castile in secret disguised as a

merchant. Finally, on 19 October 1469 they married in the Palacio de los Vivero in the city of Valladolid. Once

Henry found out about the marriage he quickly urged the Pope to

dissolve the marriage using the grounds of Isabella and Ferdinand’s kinship as second cousins by descent from John I of Castile. But Pope Sixtus IV resolved this matter by dispensing Isabella and Ferdinand with a Papal Bull.

1492 was an important year for Isabella: seeing the conquest of Granada and hence the end of the 'Reconquista' (reconquest), her successful patronage of Christopher Columbus, and her expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Spain. The Emirate of Granada had been held by the Muslim Nasrid dynasty. Protected by natural barriers and fortified towns, it had withstood the long process of the reconquista.

However, in contrast to the determined leadership by Isabella and

Ferdinand, Granada's leadership was divided and never presented a

united front. It took ten years to conquer Granada, culminating in

1492. When the Spaniards, early on, captured the ruler of Granada, Muhammad XII,

they set him free for a ransom so that he could return to Granada and

resume his reign. The Spanish monarchs recruited soldiers from many

European countries and improved their artillery with the latest and

best cannons. Systematically, they proceeded to take the kingdom piece

by piece. Often Isabella would inspire her followers and soldiers by

praying in the middle of, or close to, the battle field, that God's

will may be done. In 1485 they laid siege to Ronda, which surrendered after extensive bombardment. The following year, Lojawas taken, and again Muhammad XII was captured and released. One year later, with the fall of Málaga, the western part of the Muslim Nasrid kingdom had fallen into Spanish hands. The eastern province succumbed after the fall of Baza in

1489. The siege of Granada began in the spring of 1491. When the

Spanish camp was destroyed by an accidental fire, the camp was rebuilt,

in stone, in the form of a cross, painted white, and named Santa Fe ("Holy

Faith"). At the end of the year, Muhammad XII surrendered. On 2 January

1492 Isabel and Ferdinand entered Granada to receive the keys of the

city and the principal mosque was reconsecrated as a church. The Treaty of Granada signed later that year was to assure religious rights to the Muslims, which did not last. Queen Isabella rejected Christopher Columbus's plan to reach the Indies by

sailing west more than three times before changing her mind. It

actually took her about 1-2 years to agree to his plan. His conditions

(the position of Admiral; governorship for him and his descendants of

lands to be discovered; and ten percent of the profits) were met. On

3 August 1492 his expedition departed and arrived in America on October

12. He returned the next year and presented his findings to the

monarchs, bringing natives and gold under a hero's welcome. Spain

entered a Golden Age of exploration and colonization. In 1494, by the Treaty of Tordesillas, Isabella and Ferdinand agreed to divide the Earth, outside of Europe, with king John II of Portugal.

With the institution of the Roman Catholic Inquisition in Spain, and with the Dominican friar Tomás de Torquemada as

the first Inquisitor General, the Catholic Monarchs pursued a policy of

religious unity. Though Isabella opposed taking harsh measures against

Jews on economic grounds, Torquemada was able to convince Ferdinand. On

31 March 1492, the Alhambra Decree for

the expulsion of the Jews was issued. Approximately 200,000 left Spain.

Others converted, but often came under scrutiny by the Inquisition

investigating relapsed conversos (Marranos)

and the Judaizers who had been abetting them. The Muslims of the newly

conquered Granada had been initially granted religious freedom, but

pressure to convert increased, and after some revolts, a policy of

forced expulsion or conversion was also instituted in 1502 (Moriscos). One Converso who didn't suffer from the effects of the Inquisition was Luis de Santángel,

including his family; he was the financial minister of the King and

Queen, and was of great help when it came to the discovery of the New

World. Isabella received with her husband the title of Catholic Monarch by Pope Alexander VI,

a pope of whose secularism Isabella did not approve. Along with the

physical unification of Spain, Isabella and Ferdinand embarked on a

process of spiritual unification, trying to bring the country under one

faith (Roman Catholicism). As part of this process, the Inquisition became institutionalized. After an uprising in 1499, the Treaty of Granada was broken in 1502 and Muslims were forced to either be baptized or to be expelled. Isabella's confessor, Cisneros, was named Archbishop of Toledo. He was instrumental in a program of rehabilitation of the religious institutions of Spain, laying the groundwork for the later Counter-Reformation. As Chancellor, he exerted more and more power. Isabella

and her husband had created an empire and in later years were consumed

with administration and politics; they were concerned with the

succession and worked to link the Spanish crown to the other rulers in Europe.

Politically this can be seen in attempts to outflank France and to

unite the Iberian peninsula. By early 1497 all the pieces seemed to be

in place: John, Prince of Asturias, married Archduchess Margaret of Austria, establishing the connection to the Habsburgs. The eldest daughter, Isabella, married Manuel I of Portugal, and Joanna was married to another Habsburg prince, Philip of Burgundy. However, Isabella's plans for her children did not work out. John died shortly after his marriage. Isabella, Princess of Asturias, died in childbirth and her son Miguel died at the age of two. Queen Isabella I's crowns passed to her daughter, Joanna the Mad, and her son-in-law, Philip the Handsome. Isabella died in 1504 in Medina del Campo, before Philip and Ferdinand became enemies. She is entombed in Granada in the Capilla Real, which was built by her grandson, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (Carlos

I of Spain), alongside her husband Ferdinand, her daughter Joanna and

Joanna's husband Philip; and Isabella's 2-year old grandson, Miguel

(the son of Isabella's daughter, also named Isabella, and King Manuel I

of Portugal). The museum next to the Capilla Real houses her crown and scepter.