<Back to Index>

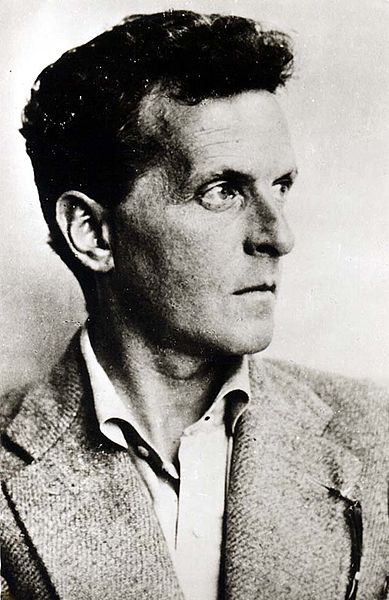

- Philosopher Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein, 1889

- Painter Eugène Delacroix, 1798

- Emperor of the Roman Empire Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, 121

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language.

Described by Bertrand Russell as "the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived, passionate, profound, intense, and dominating," Wittgenstein is considered by many to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century. Helping to inspire two of the century's principal philosophical movements, the Vienna Circle and Oxford ordinary language philosophy, he is considered one of the most important figures in analytic philosophy. Wittgenstein's influence has been felt in nearly every field of the humanities and social sciences, yet there are widely diverging interpretations of his thought.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was born in Vienna on 26 April 1889, to Karl and

Leopoldine Wittgenstein. He was the youngest of eight children, born

into one of the most prominent and wealthy families in the Austro-Hungarian empire. His father's parents, Hermann Christian and Fanny Wittgenstein (who was a first cousin of the famous violinist Joseph Joachim), were both born into Jewish families but later converted to Protestantism, and after they moved from Saxony to Vienna in the 1850s, assimilated into the Viennese Protestant professional

classes. Ludwig's father, Karl Wittgenstein, became an industrialist

and went on to make his fortune in iron and steel. By the late 1880s,

Karl controlled an effective monopoly on steel and iron resources within the empire, and was one of the richest men in the world. Eventually,

Karl transferred much of his capital into real estate, shares of

stocks, precious metals, and foreign currency reserves, which were

spread across Switzerland, Austria, the Netherlands and North America.

Consequently, the family's colossal wealth was insulated from the

inflation crises that followed in subsequent years. Ludwig's mother, Leopoldine Kalmus, was born to a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, and was an aunt of the Nobel Prize laureate Friedrich von Hayek on her maternal side. Despite his paternal grandparents' conversion to Protestantism, the Wittgenstein children were baptized as Roman Catholics — the faith of their maternal grandmother — and Ludwig was given a Roman Catholic burial upon his death.

Ludwig grew up in a household that provided an exceptionally intense

environment for artistic and intellectual achievement. His parents were

both very musical and all their children were artistically and

intellectually educated. Karl Wittgenstein was a hugely successful

steel tycoon, but also became a leading patron of the arts. He

commissioned works by Rodin and Klimt, and fully financed the Vienna Secession Building. The Wittgenstein house hosted many figures of high culture — but above all, musicians. The family was often visited by composers such as Johannes Brahms, Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler.

Brahms had given piano lessons to Ludwig's two eldest sisters, and

debut recitals for some of his major works were performed in the

family's music rooms. Ludwig's older brother Paul Wittgenstein went on to become a world-famous concert pianist, even after losing his right arm in World War I. Ludwig himself had absolute pitch perception, and

his devotion to music remained vitally important to him throughout his

life: he made frequent use of musical examples and metaphors in his

philosophical writings, and was said to be unusually adept at whistling

lengthy and detailed musical passages. He also played the clarinet and is said to have remarked that he approved of this instrument because it took a proper role in the orchestra. His family also had a history of intense self-criticism, to the point of depression and suicidal tendencies.

Three of his four brothers committed suicide. The eldest of the

brothers, Hans — an early musician who started composing at age

four — killed himself in April 1902 in Havana, Cuba.

The third son, Rudolf, followed in May 1904 in Berlin. Their brother

Kurt shot himself at the end of World War I, in October 1918, when the

Austrian troops he was commanding deserted en masse. Until 1903, Ludwig was educated by private tutors at home; after that, he began three years of schooling at the Realschule in Linz, a school emphasizing technical topics. For one school year, Adolf Hitler,

who was born a mere six days before Wittgenstein, was a student there,

but two grades below Wittgenstein, when both boys were 14 or 15 years

old. It

is unknown whether Hitler and Wittgenstein even knew of each other,

and, if so, whether either had any memory of the other. At

the school, Wittgenstein spoke in an upper-class accent, with a slight

stutter, wore very elegant clothes, and was highly sensitive and

extremely unsociable. It was one of his idiosyncrasies to use the

formal form of address with his classmates and to aggressively demand

that they too (with the exception of a single acquaintance) address him

formally, with "Sie" and "Herr Ludwig". In 1905 Ludwig Boltzmann's

collection of popular writings, including an inspiring essay about the

hero and genius who would solve the problem of heavier-than-air flight

("On Aeronautics") was published and Wittgenstein wanted to study Physics with Boltzmann, however Boltzmann committed suicide in 1906. In 1906, Wittgenstein began studying mechanical engineering in Berlin, and in 1908 he went to the Victoria University of Manchester to study for his doctorate in engineering,

full of plans for aeronautical projects. He registered as a research

student in an engineering laboratory, where he conducted research on

the behaviour of kites in the upper atmosphere,

and worked on the design of a propeller with small jet engines on the

end of its blades. During his research in Manchester, he became

interested in the foundations of mathematics, particularly after reading Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell's Principia Mathematica and Gottlob Frege's Grundgesetze der Arithmetik, vol. 1 (1893) and vol. 2 (1903). In

the summer of 1911 Wittgenstein visited Frege and, after having

corresponded with him for some time, was advised by Frege to attend the University of Cambridge to study under Russell. In October 1911, Wittgenstein arrived unannounced at Russell's rooms in Trinity College and

was soon attending his lectures and discussing philosophy with him at

great length. He made a great impression on Russell (who soon became

convinced of his genius) and G. E. Moore, and started to work on the foundations of logic and mathematical logic. Russell

was by this time increasingly tired of philosophy and envisaged

Wittgenstein as his successor who would carry on his work in the

foundations of mathematics. He

was also frequently overpowered by the latter's forceful personality

and criticisms. Faced with criticisms of his work by Wittgenstein,

Russell wrote "I saw that he was right, and I saw that I could not hope

ever again to do fundamental work in philosophy." During this period, Wittgenstein's other major interests were music and traveling (he went to Iceland in September 1912), often in the company of David Pinsent, an undergraduate who became a firm friend. He was also invited to join the Cambridge Apostles, an elite secret society that Russell and Moore had both belonged to as students. While in Cambridge, Wittgenstein often liked to go to the cinema. Wittgenstein's father died in 1913. On receiving his inheritance, Wittgenstein became one of the wealthiest men in Europe. He donated some of it, initially anonymously, to Austrian artists and writers, including Rainer Maria Rilke and Georg Trakl.

In 1914, he went to visit Trakl, when the latter wanted to meet his

benefactor, but Trakl died (an apparent suicide) days before

Wittgenstein arrived. This is the second instance of someone committing

suicide just when Wittgenstein wanted to meet them (after Boltzmann in 1906). Although

he was invigorated by his study in Cambridge and his conversations with

Russell, Wittgenstein came to feel that he could not get to the heart

of his most fundamental questions while surrounded by other academics.

In 1913, he retreated to the relative solitude of the remote village of Skjolden at the end of the Sognefjord in Norway. Here

he rented the second floor of a house and stayed for the winter. The

isolation from academia allowed him to devote himself entirely to his

work, and he later saw this period as one of the most passionate and

productive times of his life. While there he wrote a book entitled Logik, a ground-breaking work in the foundations of logic which was the immediate predecessor and source of much of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. The outbreak of World War I in

the next year took him completely by surprise and left him in deep

shock when he learned of it, as he was living in seclusion. He

volunteered for the Austro-Hungarian army, first serving on a ship and then in an artillery workshop. In 1916, he was sent as a member of a howitzer regiment to the Russian front, where he won several medals for bravery, then in the Italian Southern Tyrol (today Trentino, in Italy), where he was taken as a prisoner of war by the Italian army in November 1918 near Trento. His

notebook entries during the war reflect his contempt for the baseness,

as he saw it, of soldiers in wartime. Throughout the war, Wittgenstein

kept notebooks in which he frequently wrote philosophical and religious

reflections alongside personal remarks. The notebooks reflect a

profound change in his religious life: an agnostic during his stint at

Cambridge, Wittgenstein discovered Leo Tolstoy's The Gospel in Brief at a bookshop in Galicia.

He carried the book everywhere he went and recommended it to anyone in

distress (to the point that he became known to his fellow soldiers as

"the man with the gospels"). Wittgenstein's other religious influences include Saint Augustine, Fyodor Dostoevsky and, most notably, Søren Kierkegaard, whom Wittgenstein referred to as "a saint". Wittgenstein's work on Logic began

to take on an ethical and religious significance. With this new concern

with the ethical, combined with his earlier interest in logical

analysis, and with key insights developed during the war (such as the

so-called "picture theory" of propositions), Wittgenstein's work from

Cambridge and Norway was transfigured into the material that eventually became the Tractatus. Toward the end of the war in 1918, Wittgenstein was promoted to reserve officer (lieutenant) and sent to northern Italy as

part of an artillery regiment. On leave in the summer of 1918, he

received a letter from David Pinsent's mother telling Wittgenstein that

her son had been killed in an airplane accident. Suicidal, Wittgenstein

went to stay with his uncle Paul, and there completed the Tractatus, which he dedicated to Pinsent. The book was then sent to publishers, but without success. In

October 1918, Wittgenstein returned to the Italian front but was

captured by the Italians shortly thereafter. While he was a prisoner of

war at Cassino (Central Italy), through the intervention of his Cambridge friends, Russell and Keynes, Wittgenstein managed to get access to books, prepare his manuscript, and send it back to England.

Russell recognized it as a work of supreme philosophical importance and

worked with Wittgenstein to get it published after his release in 1919.

An English translation was prepared, first by Frank P. Ramsey and then by C. K. Ogden, with Wittgenstein's involvement. After some discussion of how best to translate the title, G. E. Moore suggested Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, an allusion to Baruch Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. Russell wrote an introduction, lending the book his reputation as one of the foremost philosophers in the world. However,

difficulties remained. Wittgenstein had become personally disaffected

with Russell and was displeased with Russell's introduction, which he

thought evinced a fundamental misunderstanding of the Tractatus. Wittgenstein grew frustrated as interested publishers proved difficult to find. To add insult to injury, those publishers who were interested proved to be so mainly because of Russell's introduction. Finally Wilhelm Ostwald's journal Annalen der Naturphilosophie printed

a German edition in 1921, and Routledge and Kegan Paul printed a

bilingual edition with Russell's introduction and the Ramsey-Ogden

translation in 1922. By

then, Wittgenstein was a profoundly changed man. He faced harrowing

combat in World War I, and crystallized his intellectual and emotional

upheavals with the exhausting composition of the Tractatus.

It was a work that transfigured all of his past work on logic into a

radically new framework that he believed offered a definitive solution

to all the

problems of philosophy. These changes in Wittgenstein's inner and outer

life left him both haunted and yet invigorated to follow a new, ascetic

life. One of the most dramatic expressions of this change was his

decision in 1919 to give away the portion of the family fortune he had

inherited when his father died. The money was divided between his

sisters Helene and Hermine and his brother Paul, and Wittgenstein

insisted that they promise never to give it back. He felt that giving

money to the poor could only corrupt them further, whereas the rich

would not be harmed by it. Wittgenstein, without suffering the weight of humility, thought that his book Tractatus had solved all the problems there were and could ever be regarding philosophy and he left for Austria to

train as a primary school teacher, indicating that that was the natural

and rational next step after writing a book on philosophy. He

was educated in the methods of the Austrian School Reform Movement

which advocated the stimulation of the natural curiosity of children

and their development as independent thinkers, instead of just letting

them memorize facts. Wittgenstein was enthusiastic about these ideas

but ran into problems when he was appointed as an elementary teacher in

the rural Austrian villages of Trattenbach, Puchberg-am-Schneeberg, and Otterthal.

He achieved good results with children attuned to his interests and

style of teaching, but he had unrealistically high expectations of the

rural primary school children he taught, and his teaching methods were

extremely intense and highly exacting—he had little patience with those

children who had no aptitude for what was taught. His severe

disciplinary methods (often involving striking the children harshly and

other forms of corporal punishment) — as well as a general suspicion

amongst the villagers that he was somewhat mad (which his strange

antics did not help in alleviating) — led to a long series of bitter

disagreements with some of his students' parents. This eventually

culminated in April 1926 with the collapse of an eleven-year-old boy

whom Wittgenstein had struck on the head. The

boy's father attempted to have Wittgenstein arrested, and despite being

cleared of misconduct, he resigned his position and returned to Vienna,

feeling that he had failed as a primary school teacher. During

his time as a school teacher, Wittgenstein wrote a pronunciation and

spelling dictionary for his own use in teaching students. The

publishers insisted upon the removal of Wittgenstein's introduction (on

the grounds that the dictionary ironically had grammatical errors) and

some additions to the list of words, and it was moderately

well-received by his colleagues (although not reprinted in his

lifetime). This would be the only book besides the Tractatus that Wittgenstein published in his lifetime. After

abandoning his work as a school teacher, Wittgenstein worked as a

gardener's assistant in a monastery near Vienna, after being convinced

that it would be more fulfilling to be a gardener's assistant rather

than a gardener. He considered becoming a monk, but

despite his reputed determination and stability, went only so far as to

enquire about the requirements for joining an order. Two major

developments helped to save Wittgenstein from this despairing state.

The first was an invitation from his sister Margaret ("Gretl") Stonborough, (whose portrait was painted by Gustav Klimt in 1905), to work on the design and construction of her new house. He worked with the architect, Paul Engelmann,

who had become his lover during the war, when they spent a lot of time

in each other's company in the trenches, and the two designed a spare

modernist house after the style of Adolf Loos (whom

they both greatly admired). Wittgenstein found the work extremely

intellectually absorbing and exhausting; he poured himself into the

design in painstaking detail, including even small aspects such as

doorknobs, kitchen faucets, bath shower-heads, latrine commodes and

radiators, spending a year on each as they had to be exactly positioned

to maintain the symmetry of the rooms. As a work of modernist architecture the house evoked some high praise from his immediate family; G. H. von Wright said that it was as good as his book Tractatus.

The effort of totally involving himself in intellectual work once again

did much to restore Wittgenstein's spirits. Of the house, Ludwig's

eldest sister, Hermine, wrote: "Even though I admired the house very

much, I always knew that I neither wanted to, nor could, live in it

myself. It seemed indeed to be much more a dwelling for the gods".

Secondly, toward the end of his work on the house, Wittgenstein was contacted by Moritz Schlick, one of the leading figures of the newly formed Vienna Circle. The Tractatus had

been tremendously influential in the development of Viennese positivism

and, although Schlick never succeeded in drawing Wittgenstein into the

discussions of the Vienna Circle itself, he and some of his fellow

circle members, especially Friedrich Waismann, met occasionally with Wittgenstein to discuss philosophical topics. Wittgenstein

was frequently frustrated by these meetings — he believed that Schlick

and his colleagues had fundamentally misunderstood the Tractatus.

Many of the disagreements concerned the importance of religious life

and the mystical; Wittgenstein considered these matters as a sort of

wordless faith, whereas the positivists disdained them as useless. In

one meeting, Wittgenstein went so far as to refuse to discuss the book

at all, and sat with his back to his guests sulking, while he read

aloud from the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore,

much to the vexation of his guests. Nevertheless, the contact with the

Vienna Circle stimulated Wittgenstein intellectually and revived his

interest in philosophy. He also met with Frank P. Ramsey,

a young philosopher of mathematics who traveled several times from

Cambridge to Austria to meet with Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle.

In the course of his conversations with the Vienna Circle and with

Ramsey, Wittgenstein began to think that there might be some "grave

mistakes" in his work as presented in the Tractatus —

marking the beginning of a second career of ground-breaking

philosophical work, which would occupy him for the rest of his life. At

the urging of Ramsey and others, in 1929 Wittgenstein decided to return

to Cambridge. He was met at the railway station by a crowd of England's

greatest intellectuals, discovering rather to his horror that he was

one of the most famed philosophers in the world. In a letter to his

wife, Lydia Lopokova, Wittgenstein's old friend John Maynard Keynes wrote: "Well, God has arrived. I met him on the 5.15 train." Despite

this fame, he could not initially work at Cambridge as he did not have

a degree, so he applied as an advanced undergraduate. Russell noted

that his previous residency was in fact sufficient for a doctoral

degree, and urged him to offer the Tractatus as a doctoral thesis,

which he did in 1929. It was examined by Russell and Moore; at the end

of the thesis defence, Wittgenstein clapped the two examiners on the

shoulder and said, "Don't worry, I know you'll never understand it." Moore

commented in the examiner's report: "I myself consider that this is a

work of genius; but, even if I am completely mistaken and it is nothing

of the sort, it is well above the standard required for the Ph.D.

degree." Wittgenstein was appointed as a lecturer and was made a fellow of Trinity College. Although

Wittgenstein was involved in a relationship with Marguerite Respinger

(a young Swiss woman he had met as a friend of the family), his plans

to marry her were broken off in 1931 and he never married. Most of his

romantic attachments were to young men. There is considerable debate

over how active Wittgenstein's homosexual life was, inspired by W. W. Bartley's claim to have found evidence of not only active homosexuality but in particular several casual liaisons with young men in the Wiener Prater park

during his time in Vienna. Bartley published his claims in a biography

of Wittgenstein in 1973, claiming to have his information from

"confidential reports from... friends" of Wittgenstein, whom

he declined to name, and to have discovered two coded notebooks unknown

to Wittgenstein's executors that detailed the visits to the Prater.

Wittgenstein's estate and other biographers disputed Bartley's claims

and asked him to produce the sources that he claims. What has become

clear, at least, is that Wittgenstein had several long-term homoerotic

attachments, including an infatuation with his friends David Pinsent, Francis Skinner, and Ben Richards. Although some commentators have assumed that Wittgenstein's political sympathies lay on the left,

and while, despite being entirely contemptuous of Marx's philosophical

work, he once described himself as a "communist at heart" and

romanticized the life of laborers,

in many ways he was a reactionary. He abhorred the idea of scientific

progress (for the reason that it was meaningless without moral

progress), was conservative in his musical tastes, and was ambivalent

about the invention of nuclear weapons, stating that "the people making

speeches against producing the bomb are undoubtedly the scum of the

intellectuals, although even this does not prove beyond question that

what they abominate is to be welcomed". He particularly admired the philosophy of the Austrian Otto Weininger. Wittgenstein distributed copies of Weininger's theories to bemused colleagues at Cambridge. Like Weininger, Wittgenstein had a troubled relationship towards his ethnicity and sexuality. In

his notebooks of the early 1930s, in particular (MS 154), he critically

berated himself for being a "reproductive" as opposed to "productive"

thinker, and attributed this to his own Jewish and diasporadic sense of

identity, writing: "The saint is the only Jewish genius. Even the

greatest Jewish thinker is no more than talented. (Myself for

instance)". While Wittgenstein would later claim that "[m]y thoughts are 100% Hebraic", as

Hans Sluga has argued, if so, "his was a self-doubting Judaism, which

had always the possibility of collapsing into a destructive self-hatred

(as it did in Weininger's case) but which also held an immense promise

of innovation and genius." In 1934, attracted by his friend Keynes' description of Soviet life in Short View of Russia, he conceived the idea of emigrating to the Soviet Union with

Skinner. They took lessons in Russian and in 1935 Wittgenstein traveled

to Leningrad and Moscow in an attempt to secure employment. He was

offered teaching positions but preferred manual work and returned three

weeks later. From 1936 to 1937, Wittgenstein lived again in Norway, leaving Skinner behind. He worked on the Philosophical Investigations.

In the winter of 1936/37, he delivered a series of "confessions" to

close friends, most of them about minor infractions like white lies, in

an effort to cleanse himself. In 1938, he traveled to Ireland to

visit Maurice Drury, a friend who was training as a doctor, and

considered such training himself, with the intention of abandoning

philosophy for psychiatry. The visit to Ireland was at the same time a response to the invitation of the then Irish Taoiseach, Eamon de Valera,

himself a mathematics teacher. De Valera hoped that Wittgenstein's

presence would contribute to an academy for advanced mathematics. While he was in Ireland, Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss; the Viennese Wittgenstein was now a citizen of the enlarged Germany and a Jew under

its racial laws. He found this intolerable and started to investigate

the possibilities of acquiring British or Irish citizenship with the

help of Keynes, but this put his siblings Hermine, Helene and Paul, all

still living in Austria, in considerable danger. Wittgenstein's first

thought was to travel to Vienna, but he was dissuaded by friends. Had

the Wittgensteins been classified as Jews, their fate would have been

the same as other Austrian Jews, only a minority of whom survived the

war. Their only hope was to be classified as Mischlinge:

Aryan/Jewish crossbreeds, whose treatment, while harsh, was less brutal

than that reserved for Jews. This reclassification was known as a

"Befreiung". The successful conclusion of these negotiations required

the personal approval of Adolf Hitler. "The figures show how difficult

it was to gain a Befreiung. In 1939 there were 2,100 applications for a

different racial classification: the Führer allowed only twelve." Gretl,

an American citizen by marriage, started negotiations with the Nazi

authorities over the racial status of their grandfather Hermann, claiming that he was the illegitimate son of an "Aryan". The Reichsbank was

keen to get its hands on the large amounts of foreign currency owned by

the Wittgenstein family, and this was used as a bargaining tool. Paul,

who had escaped to Switzerland and then the United States in July 1938,

disagreed with the family's stance. In the summer of 1937, Wittgenstein had been introduced to Alan Turing by Alister Watson. After

G. E. Moore's resignation in 1939, Wittgenstein, who was by then

considered a philosophical genius, was appointed to the chair in

Philosophy at Cambridge. He acquired British citizenship soon

afterwards, and in July 1939 he traveled to Vienna to assist Gretl and

his other sisters, visiting Berlin for one day to meet with an official

of the Reichsbank. After this, he traveled to New York to persuade

Paul, whose agreement was required, to back the scheme. The required

Befreiung was granted in August 1939. The unknown amount signed over to

the Nazis by the Wittgenstein family, a week or so before the outbreak

of war, included amongst many other assets 1.7 tonnes of gold. At

2009 prices, this amount of gold alone would be worth in excess of

US$60 million. Had the transfer occurred only weeks later, it would

have counted as aiding an enemy state in time of war, for which the

maximum penalty was death by hanging. There

is also a report that Wittgenstein went on in 1939 from Berlin to visit

Moscow a second time and met again the philosopher/academician Sophia Janowskaya. After exhausting philosophical work, Wittgenstein would often relax by watching a Western movie, where he preferred to sit at the very front of the cinema, or reading detective stories. These tastes are in stark contrast to his preferences in music, where he rejected anything after Brahms as a symptom of the decay of society. By this time, Wittgenstein's view on the foundations of mathematics had

changed considerably. Earlier he had thought that logic could provide a

solid foundation, and he had even considered updating Russell and

Whitehead's Principia Mathematica.

Now he denied that there were any mathematical facts to be discovered

and he denied that mathematical statements were "true" in any real

sense. He gave a series of lectures on the foundations of mathematics, discussing this and other topics, documented in a book. The

book contains lectures by Wittgenstein as well as discussions between

Wittgenstein and several attending students including the young Alan

Turing. During World War II, he left Cambridge and volunteered as a hospital porter in Guy's Hospital in London and as a laboratory assistant in Newcastle upon Tyne's Royal Victoria Infirmary. This was arranged by his friend John Ryle, a brother of the philosopher Gilbert Ryle,

who was then working at the hospital. After the war, Wittgenstein

returned to teach at Cambridge, but he found teaching an increasing

burden: he had never liked the intellectual atmosphere at Cambridge,

and in fact encouraged several of his students, including Skinner, to

find work outside of academic philosophy. There are stories, perhaps

apocryphal, that if any of his philosophy students expressed an

interest in pursuing the subject, he would ban them from attending any

more of his classes. Wittgenstein

resigned his position at Cambridge in 1947 to concentrate on his

writing. He was succeeded as professor by his friend Georg Henrik von Wright. He stayed at Kilpatrick House guesthouse in East Wicklow in 1947 and 1948. Much of his later work was done on the west coast of Ireland in the rural isolation he preferred with Patrick Lynch. By 1949, when he was diagnosed as having prostate cancer, he had written most of the material that would be published after his death as Philosophische Untersuchungen (Philosophical Investigations). He spent the last two years of his life working in Vienna, the United States,

Oxford, and Cambridge. He worked continuously on new material, inspired

by the conversations that he had had with his friend and former student Norman Malcolm during

a summer spent at the Malcolms' house in the United States. Malcolm had

been wrestling with G.E. Moore's commonsense response to external world skepticism ("Here

is one hand, and here is another; therefore I know at least two

external things exist"). Wittgenstein began to work on another series

of remarks inspired by his conversations, which he continued to work on

until two days before his death, and which were published posthumously

as On Certainty. Wittgenstein wrote the final entry, in manuscript MS 177, less

than a day before he completely lost consciousness. His last words,

reported by the wife of his doctor, in whose home he spent his last

days, were: "Tell them I've had a wonderful life". He was given a Roman Catholic burial and interred at the Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge.