<Back to Index>

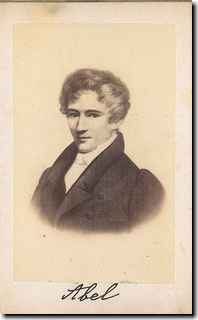

- Mathematician Niels Henrik Abel, 1802

- Novelist Henri René Albert Guy de Maupassant, 1850

- 1st President of the Republic of Brazil Manuel Deodoro da Fonseca, 1827

Niels Henrik Abel (August 5, 1802 – April 6, 1829) was a noted Norwegian mathematician who proved the impossibility of solving the quintic equationin radicals.

Abel was born in Nedstrand, Norway, as second child to Søren Georg Abel and Anne Marie Simonsen. When he was born the family lived at the rectory at Finnøy.

Much suggests that Niels Henrik was born in the neighboring parish, as

their parents were guests at the bailiff in Nedstrand in July / August

of his year of birth. Abel's father, Søren Georg Abel, had a degree in theology and philosophy and served as pastor at Finnøy. Abel's grandfather, Hans Mathias Abel, was pastor at Gjerstad near Risør.

After the latter's death, in 1804, Søren Georg Abel was

appointed pastor at Gjerstad and the family moved there. Søren

Georg Abel spent his childhood, and had also served as chaplain, at

Gjerstad. Anne Marie Simonsen was from Risør and her father,

Niels Henrik Saxild Simonsen, was a tradesman and merchant ship-owner.

He was said to be the richest person in Risør. Anne Marie had

grown up with two step-mothers, in relative luxurious surroundings. At

Gjerstad rectory she enjoyed arranging balls and social gatherings.

Much suggests she was early on an alcoholic and took little interest in

the upbringing of the children. Niels

Henrik and his brothers were lectured by their father, with handwritten

books to read. Interestingly, a subtraction table in a book of

mathematics reads 1-0=0.

With the independence and first election of Norway in 1814, Abel's father was voted in as a representative to the Storting. Meetings of the Storting were until 1866 held in the main hall of the Cathedral School in Christiania (now

known as Oslo). Most certainly this is how he got in contact with the

school, and decided his eldest son, Hans Mathias, was to start next

year. When the time for departure approached, the boy was so saddened

and depressed over having to leave home, that his father did not dare

send him away. He decided to send Niels Henrik instead. In 1815, Abel entered the Cathedral School,

aged 13. Hans Mathias Abel, joined him the next year. They shared

apartment and had classes together. His brother did, in general, get

better grades than Niels Henrik Abel. A new mathematics teacher, Bernt Michael Holmboe,

was appointed in 1818. He gave the students mathematical tasks to do at

home. Seeing Abel's talent in mathematics he encouraged him to study

the subject to an advanced level. He also gave Abel private lectures

after school. In 1818 Abel's father had a public theological argument with Stener Johannes Stenersen regarding

Abel's catechism from 1806. The argument was well covered in press and

Abel was not doing well. He was given the nickname "Abel

Treating" (Norwegian: "Abel Spandabel"). Niels Henrik Abel's

reaction to the quarrel was said to be "excessive gaiety". At the same

time Abel's father almost faced impeachment after insulting Carsten Anker, the host of the Norwegian Constituent Assembly.

In September 1818, he returned to Gjerstad with his political career in

ruins. He began drinking heavily. Abel's father died in 1820, aged 48.

In his funeral, with the rectory full of guests, widowed Anne Marie

Abel, got drunk and went openly to bed with one of the servants. The

two brothers reacted differently to the decline of the family. At

school, Niels Henrik did extremely well in mathematics, however he was

struggling in other subjects. Hans Mathias went into a serious

depression, never to recover. Hans Mathias quit school and returned to

Gjerstad shortly before their father died. The family was left in

strained circumstances. Anne Marie Abel's once rich father, had also

faced decline. He went bankrupt in a recession after the Napoleonic Wars, and died also in 1820. Holmboe supported Abel with a scholarship to remain at school and raised money from his friends to enable Abel to study at the Royal Frederick University. Abel

entered the university in 1821. He was already the most knowledgeable

mathematician in Norway. Holmboe had nothing more he could teach him

and Abel had studied all the latest mathematical literature in the

University library. Abel had also started work on his first

achievement, the quintic equation in

radicals. Abel initially thought he had found the solution to the

quintic equation in radicals in 1821. Mathematicians had been looking

for a solution on this problem for over 250 years. The two professors

in Christiania, Søren Rasmussen and Christopher Hansteen, found no errors in Abel's formulas, and sent the work on to the leading mathematician in the Nordic countries, Professor Ferdinand Degen in

Copenhagen. He also found no faults, but still doubted that the

solution that so many outstanding mathematicians had sought after, now

really should have been found by an unknown student in the distant

Christiania. Degen noted however Abel's unusual sharp mind and

believed that such a talented young man should not use its powers in

such a "sterile object" as the fifth degree equation, but rather on Elliptic Functions and Transcendence, for then, writes Degen, he will "discover Magellanian thoroughfares to large portions of a vast analytical ocean". Degen

asked Abel to give a numerical example of his method and, while trying

to provide an example, Abel discovered a mistake in his paper. Abel graduated in 1822. His performance was medium, except in mathematics. After

he graduated, professors from university supported him financially and

professor Christopher Hansteen let him live in a room in the attic of

his home. He was later to view Ms. Hansteen as his second mother. While

living here, Niels Henrik Abel helped a younger brother, Peder Abel,

through to examen artium.

He also helped a sister, Elisabeth, to find work in town. In spring 1823

Abel published his first article in "Magazin for Naturvidenskaberne",

Norway's first journal on sciences and co-founded by professor

Hansteen. He published a few articles, but the journal soon understood

that this was not material for the common reader. In 1823 he also wrote

a paper in French. It was "a general representation of the possibility

to integrate all differential formulas". He applied for funds at the university to publish it, however the work was lost, never to be refound, while being reviewed. In summer 1823 professor Rasmussen gave Abel a gift of 100 speciedaler so he could travel to Copenhagen and visit Ferdinand Degen and other mathematicians there. While there he did some work on Fermat's Last Theorem. Abel's uncle, Peder Mandrup Tuxen, lived at the naval base in Christianshavn, Copenhagen. At a ball there, he met Christine Kemp, his future fiancee. She moved in 1824 to Son, Norway to work as governess. They got engaged Christmas 1824. After

returning from Copenhagen, Abel applied for a government scholarship in

order to visit top mathematicians in Germany and France. Instead, he

was granted 200 speciedaler yearly for two years, to stay in Cristiania

and learn German and French. The next two years he was promised a

scholarship of 600 speciedaler yearly and he would then be permitted to

travel abroad. While

learning languages, Abel published his first notable work in 1824,

Mémoire sur les équations algébriques où on

démontre l'impossibilité de la résolution de

l'équation générale du cinquième

degré (Memoir on algebraic equations, in which the impossibility

of solving the general equation of the fifth degree is proven). Abel

had proved the impossibility of solving the quintic equation in

radicals in 1823 (now referred to as the Abel–Ruffini theorem).

This publication was in abstruse and difficult form, in part because he

had restricted himself to only six pages, in order to save money on

printing. A more detailed proof was published in 1826 in the first

volume of Crelle's Journal. In 1825 Abel wrote a personal letter to King Carl Johan of Norway/Sweden requesting

permission to travel abroad immediately. He was permitted. In September

1825 he left Christiania. The terms for his scholarship was that he was

to visit Gauss in Göttingen and then continue to Paris. When he came to Copenhagen he changed plans. He wanted to go to Berlin instead. On the way he visited the astronomer Heinrich Christian Schumacher in Altona, now a district of Hamburg. He spent four months in Berlin, where he became well acquainted with August Leopold Crelle, who was then about to publish his mathematical journal, Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik.

This project was warmly encouraged by Abel, who contributed much to the

success of the venture. Abel contributed with seven articles in its

first year of issue. From

Berlin he went to Freiburg, and here he did brilliant research in the

theory of functions: elliptic, hyperelliptic, and a new class now known

as abelian functions being particularly intensely studied. In 1826 Abel moved to Paris,

and during a ten-month stay he met the leading mathematicians of

France; but he was poorly appreciated, as his work was scarcely known,

and his modesty restrained him from proclaiming his research. Abel's

limited finances finally compelled him to abandon his tour, and on his

return to Norway he taught for some time at Christiania.

At the age of 16, Abel gave a proof of the binomial theorem valid

for all numbers, extending Euler's result which had only held for

rationals. At age 19, he showed there is no general algebraic solution

for the roots of a quintic equation, or any general polynomial equation

of degree greater than four, in terms of explicit algebraic operations.

To do this, he invented (independently of Galois) an extremely

important branch of mathematics known as group theory,

which is invaluable not only in many areas of mathematics, but for much

of physics as well. Among his other accomplishments, Abel wrote a

monumental work on elliptic functions which, however, was not

discovered until after his death. When asked how he developed his

mathematical abilities so rapidly, he replied "by studying the masters,

not their pupils."

While

in Paris, Abel had contracted tuberculosis. During Christmas 1828, he

traveled by sled to again visit his fiancée in Froland. He became seriously ill on the journey, although a temporary

improvement allowed the couple to enjoy the holiday together. Crelle,

at the same time, had been searching for a new job for Abel in Berlin,

and did manage to have him appointed professor at a university. Crelle

wrote to Abel on April 8, 1829 to tell him the good news, but Abel had

died two days earlier.