<Back to Index>

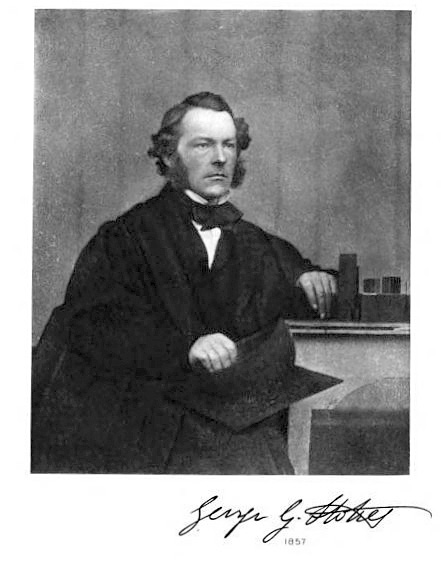

- Mathematician Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1819

- Director Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock, 1899

- Cuban Revolutionary Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz, 1926

Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1st Baronet FRS (13 August 1819 – 1 February 1903), was a mathematician and physicist, who at Cambridge made important contributions to fluid dynamics (including the Navier–Stokes equations), optics, and mathematical physics (including Stokes' theorem). He was secretary, then president, of the Royal Society.

George Stokes was the youngest son of the Reverend Gabriel Stokes, rector of Skreen, County Sligo, Ireland, where he was born and brought up in an evangelical Protestant family. After attending schools in Skreen, Dublin, and Bristol, he matriculated in 1837 at University of Cambridge, where four years later, on graduating as senior wrangler and first Smith's prizeman, he was elected to a fellowship. In accordance with the college statutes, he had to resign the fellowship when he married in 1857, but twelve years later, under new statutes, he was re-elected. He retained his place on the foundation until 1902, when on the day before his 83rd birthday, he was elected to the mastership. He did not hold this position for long, for he died at Cambridge on 1 February the following year, and was buried in the Mill Road cemetery.

In 1849, Stokes was appointed to the Lucasian professorship of mathematics at Cambridge. On June 1, 1899, the jubilee of this appointment was celebrated there in a ceremony, which was attended by numerous delegates from European and American universities. A commemorative gold medal was presented to Stokes by the chancellor of the university, and marble busts of Stokes by Hamo Thornycroft were formally offered to Pembroke College and to the university by Lord Kelvin. Stokes, who was made a baronet in 1889, further served his university by representing it in parliament from 1887 to 1892 as one of the two members for the Cambridge University constituency. During a portion of this period (1885–1890) he also was president of the Royal Society, of which he had been one of the secretaries since 1854. Since he was also Lucasian Professor at this time, Stokes was the first person to hold all three positions simultaneously; Newton held the same three, although not at the same time.

Stokes was the oldest of the trio of natural philosophers, James Clerk Maxwell and Lord Kelvin being the other two, who especially contributed to the fame of the Cambridge school of mathematical physics in the middle of the 19th century. Stokes's original work began about 1840, and from that date onwards the great extent of his output was only less remarkable than the brilliance of its quality. The Royal Society's catalogue of scientific papers gives the titles of over a hundred memoirs by him published down to 1883. Some of these are only brief notes, others are short controversial or corrective statements, but many are long and elaborate treatises.

In content his work is distinguished by a certain definiteness and finality, and even of problems which, when he attacked them, were scarcely thought amenable to mathematical analysis, he has in many cases given solutions which once and for all settle the main principles. This fact must be ascribed to his extraordinary combination of mathematical power with experimental skill. From the time when in about 1840 he fitted up some simple physical apparatus in his rooms in Pembroke College, mathematics and experiment ever went hand in hand, aiding and checking each other. In scope his work covered a wide range of physical inquiry, but, as Marie Alfred Cornu remarked in his Rede lecture of 1899, the greater part of it was concerned with waves and the transformations imposed on them during their passage through various media.

His first published papers, which appeared in 1842 and 1843, were on the steady motion of incompressible fluids and

some cases of fluid motion. These were followed in 1845 by one on the

friction of fluids in motion and the equilibrium and motion of elastic

solids, and in 1850 by another on the effects of the internal friction

of fluids on the motion of pendulums. To the theory of sound he made several contributions, including a discussion of the effect of wind on

the intensity of sound and an explanation of how the intensity is

influenced by the nature of the gas in which the sound is produced.

These inquiries together put the science of fluid dynamics on a new footing, and provided a key not only to the explanation of many natural phenomena, such as the suspension of clouds in

air, and the subsidence of ripples and waves in water, but also to the

solution of practical problems, such as the flow of water in rivers and

channels, and the skin resistance of ships. His work on fluid motion and viscosity led to his calculating the terminal velocity for a sphere falling in a viscous medium. This became known as Stokes' law. He derived an expression for the frictional force (also called drag force) exerted on spherical objects with very small Reynolds numbers. His work is the basis of the falling sphere viscometer, in

which the fluid is stationary in a vertical glass tube. A sphere of

known size and density is allowed to descend through the liquid. If

correctly selected, it reaches terminal velocity,

which can be measured by the time it takes to pass two marks on the

tube. Electronic sensing can be used for opaque fluids. Knowing the

terminal velocity, the size and density of the sphere, and the density

of the liquid, Stokes' law can be used to calculate the viscosity of

the fluid. A series of steel ball bearings of

different diameter is normally used in the classic experiment to

improve the accuracy of the calculation. The school experiment uses glycerine as the fluid, and the technique is used industrially to check the viscosity of fluids used in processes. The

same theory explains why small water droplets (or ice crystals) can

remain suspended in air (as clouds) until they grow to a critical size

and start falling as rain (or snow and hail). Similar use of the equation can be made in the settlement of fine particles in water or other fluids. The CGS unit of kinematic viscosity was named "stokes" in recognition of his work. Perhaps his best-known researches are those which deal with the wave theory of light. His optical work began at an early period in his scientific career. His first papers on the aberration of light appeared in 1845 and 1846, and were followed in 1848 by one on the theory of certain bands seen in the spectrum. In 1849 he published a long paper on the dynamical theory of diffraction, in which he showed that the plane of polarization must be perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Two years later he discussed the colours of thick plates. In 1852, in his famous paper on the change of wavelength of light, he described the phenomenon of fluorescence, as exhibited by fluorspar and uranium glass, materials which he viewed as having the power to convert invisible ultra-violet radiation into radiation of longer wavelengths that are visible. The Stokes shift,

which describes this conversion, is named in Stokes' honor. A

mechanical model, illustrating the dynamical principle of Stokes's

explanation was shown. The offshoot of this, Stokes line, is the basis of Raman scattering. In 1883, during a lecture at the Royal Institution,

Lord Kelvin said he had heard an account of it from Stokes many years

before, and had repeatedly but vainly begged him to publish it. In

the same year, 1852, there appeared the paper on the composition and

resolution of streams of polarized light from different sources, and in

1853 an investigation of the metallic reflection exhibited by certain non-metallic substances. The research was to highlight the phenomenon of light polarization.

About 1860 he was engaged in an inquiry on the intensity of light

reflected from, or transmitted through, a pile of plates; and in 1862

he prepared for the British Association a valuable report on double refraction, a phenomenon where certain crystals show different refractive indices along different axes. Perhaps the best known crystal is Iceland spar, transparent calcite crytsals. A paper on the long spectrum of the electric light bears the same date, and was followed by an inquiry into the absorption spectrum of blood. The identification of organic bodies by their optical properties was treated in 1864; and later, in conjunction with the Rev. William Vernon Harcourt, he investigated the relation between the chemical composition and the optical properties of various glasses, with reference to the conditions of transparency and the improvement of achromatic telescopes.

A still later paper connected with the construction of optical

instruments discussed the theoretical limits to the aperture of

microscope objectives.

In other departments of physics may be mentioned his paper on the conduction of heat in crystals (1851) and his inquiries in connection with Crookes radiometer; his explanation of the light border frequently noticed in photographs just outside the outline of a dark body seen against the sky (1883); and, still later, his theory of the x-rays,

which he suggested might be transverse waves travelling as innumerable

solitary waves, not in regular trains. Two long papers published in

1840 — one on attractions and Clairaut's theorem, and the other on the variation of gravity at

the surface of the earth — also demand notice, as do his mathematical

memoirs on the critical values of sums of periodic series (1847) and on

the numerical calculation of a class of definite integrals and infinite series (1850) and his discussion of a differential equation relating to the breaking of railway bridges (1849), research related to his evidence given to the Royal Commission on the Use of Iron in Railway structures after the Dee bridge disaster of 1847.

But

large as is the tale of Stokes's published work, it by no means

represents the whole of his services in the advancement of science.

Many of his discoveries were not published, or at least were only

touched upon in the course of his oral lectures. An excellent example

is his work in the theory of spectroscopy. In his presidential address to the British Association in 1871, Lord Kelvin stated

his belief that the application of the prismatic analysis of light to

solar and stellar chemistry had never been suggested directly or

indirectly by anyone else when Stokes taught it to him at Cambridge University some

time prior to the summer of 1852, and he set forth the conclusions,

theoretical and practical, which he learnt from Stokes at that time,

and which he afterwards gave regularly in his public lectures at Glasgow. These

statements, containing as they do the physical basis on which spectroscopy rests, and the way in which it is applicable to the

identification of substances existing in the sun and stars, make it

appear that Stokes anticipated Kirchhoff by

at least seven or eight years. Stokes, however, in a letter published

some years after the delivery of this address, stated that he had

failed to take one essential step in the argument — not perceiving that

emission of light of definite wavelength not merely permitted, but

necessitated, absorption of light of the same wavelength. He modestly

disclaimed "any part of Kirchhoff's admirable discovery," adding that

he felt some of his friends had been over-zealous in his cause. It must

be said, however, that English men of science have not accepted this

disclaimer in all its fullness, and still attribute to Stokes the

credit of having first enunciated the fundamental principles of spectroscopy. In

another way, too, Stokes did much for the progress of mathematical

physics. Soon after he was elected to the Lucasian chair he announced

that he regarded it as part of his professional duties to help any

member of the university in difficulties he might encounter in his

mathematical studies, and the assistance rendered was so real that

pupils were glad to consult him, even after they had become colleagues,

on mathematical and physical problems in which they found themselves at

a loss. Then during the thirty years he acted as secretary of the Royal

Society he exercised an enormous if inconspicuous influence on the

advancement of mathematical and physical science, not only directly by

his own investigations, but indirectly by suggesting problems for

inquiry and inciting men to attack them, and by his readiness to give

encouragement and help.

Stokes was involved in several investigations into railway accidents, especially the Dee bridge disaster in

May 1847, and he served as a member of the subsequent Royal Commission

into the use of cast iron in railway structures. He contributed to the

calculation of the forces exerted by moving engines on bridges. The

bridge failed because a cast iron beam was used to support the loads of

passing trains. Cast iron is brittle in tension or bending, and many other similar bridges had to be demolished or reinforced. He appeared as an expert witness at the Tay Bridge disaster,

where he gave evidence about the effects of wind loads on the bridge.

The centre section of the bridge (known as the High Girders) was

completely destroyed during a storm on December 28, 1879, while an

express train was in the section, and everyone aboard died (more than

75 victims). The Board of Inquiry listened to many expert witnesses, and concluded that the bridge was As a result of his evidence, he was appointed a member of the subsequent Royal Commission into

the effect of wind pressure on structures. The effects of high winds on

large structures had been neglected at that time, and the commission

conducted a series of measurements across Britain to gain an appreciation of wind speeds during storms, and the pressures they exerted on exposed surfaces.

Stokes held conservative religious values and beliefs. In 1886, Stokes became president of the Victoria Institute, a Christian institute founded in response to the evolutionary movement of the 1860s. He gave the 1891 Gifford lectures. He was also the vice president of the British and Foreign Bible Society and was active in foreign missions doctrinal issues.