<Back to Index>

- Engineer and Architect Vladimir Grigoryevich Shukhov, 1853

- Writer and Philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1749

- Prime Minister of Canada Paul Edgar Philippe Martin, 1938

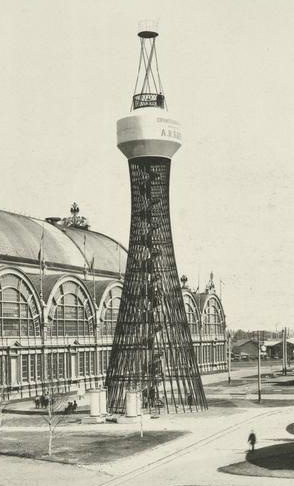

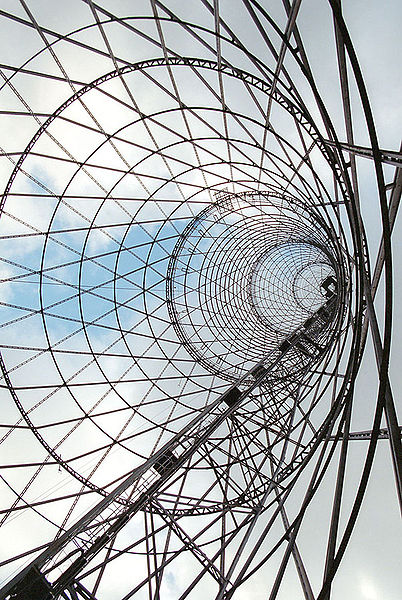

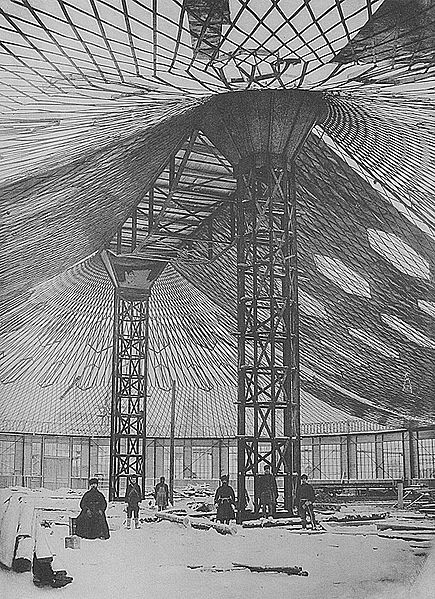

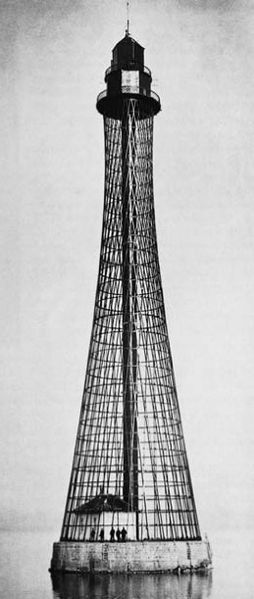

Vladimir Grigoryevich Shukhov (Russian: Владимир Григорьевич Шухов), (August 28 [O.S. August 16] 1853 - February 2, 1939) was a Russian engineer-polymath, scientist and architect renowned for his pioneering works on new methods of analysis for structural engineering that led to breakthroughs in industrial design of world's first hyperboloid structures, lattice shell structures, tensile structures, grid shell structures, oil reservoirs, pipelines, boilers, ships and barges.

Besides

the innovations he brought to the oil industry and the construction of

numerous bridges and buildings, Shukhov was the inventor of a new

family of doubly-curved structural forms. These forms, based on

non-Euclidean hyperbolic geometry, are known today as hyperboloids of revolution. Shukhov developed not only many varieties of light-weight hyperboloid towers and roof systems, but also the mathematics for their analysis. Shukhov is particularly reputed for his original designs of hyperboloid towers such as the Shukhov Tower. Vladimir Shukhov was born in the town of Graivoron, Belgorod uezd, Kursk gubernia (in present-day Belgorod Oblast)

into a petty noble family. His father Grigory Ivanovich Shukhov was a

minor government official, promoted for his efforts in the Crimean War. For a while, Grigory served as Mayor of Graivoron and later as an administrator in Warsaw. In 1864 Vladimir entered Saint Petersburg gymnasium from

which he graduated with distinction in 1871. During his high school

years he showed mathematical talents, once demonstrating to his

classmates and teacher an original proof of the Pythagorean theorem. The teacher praised his skills but he failed the grade for violating the textbook's guidelines. After graduating from the gymnasium, Shukhov entered the Imperial Moscow Technical School, in which his teachers included Pafnuty Chebyshev, Aleksey Letnikov, and Nikolay Zhukovsky.

In 1876 Shukhov graduated from the school with distinction and a Gold

Medal. Chebyshev proposed to him a job as a lecturer in mathematics at

the Imperial Moscow Technical School, but Shukhov decided to seek a job

in the industry instead. Thereupon Shukhov went to Philadelphia, to work on the Russian pavilion at the World's Fair and

to study the inner workings of the American industry. During his stay

in the US Shukhov came to know a Russian-American entrepreneur,

Alexander Veniaminovich Bari (Александр Вениаминович Бари) who also

worked on the organization of the Fair. In 1877 Shukhov returned to Russia and joined the drafting office of the Warsaw-Vienna railroad.

Within several months, Shukhov's frustration with standard and routine

engineering made him abandon the office and join a military-medical

academy. On

his coming to Russia in 1877, Bari persuaded Shukhov to give up his

medical education and to assume the office of Chief Engineer in a new

company specializing in innovative engineering. Shukhov worked with

Bari at this company until the October Revolution. Their works revolutionized many areas of civil engineering, ship engineering, and the oil industry. The thermal cracking method, the Shukhov cracking process, was patented by Vladimir Shukhov in 1891. Shukhov always found time for a passionate hobby - photography. The Photographic works of Shukhov opened new trends ahead of the flourishing of Fine art photography. He made photos in various genres: reporting, city landscape, portrait, constructivism. About two thousand photos and negatives made by Shukhov have survived until this day. After the October Revolution Shukhov decided to stay in the Soviet Union despite

having received alluring job offers from around the world. Many signal

Soviet engineering projects of the 1920s were associated with his name.

In 1919 he framed his slogan: We should work independently from politics. The buildings, boilers, beams would be needed and so would we. In the later 1930s during the Great Purge he retired from engineering work but was not arrested or persecuted. Shukov died on February 2, 1939, in Moscow and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery. His many honours included the Lenin Prize (1929) and the title of Hero of Labour (1928).