<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, 1804

- Painter Zinaida Yevgenyevna Serebriakova, 1884

- Governor General of India Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari, 1878

PAGE SPONSOR

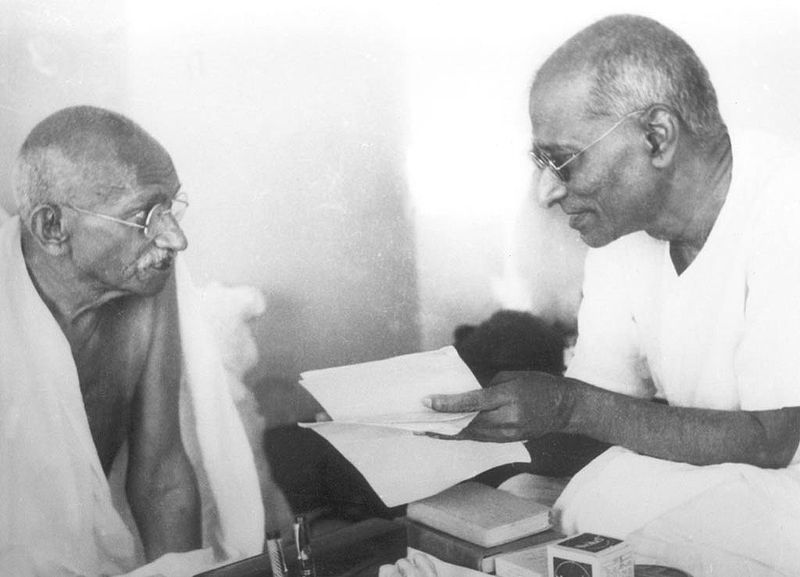

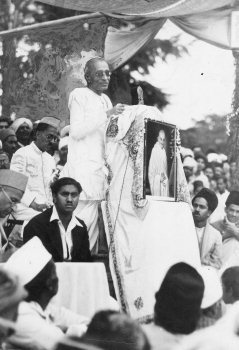

Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari (Tamil: சக்ரவர்த்தி ராஜகோபாலாச்சாரி) (10 December 1878 - 25 December 1972), informally called Rajaji or C.R., was an Indian lawyer, Indian independence activist, politician, writer, statesman and leader of the Indian National Congress who served as the last Governor-General of India. He served as the Chief Minister or Premier of the Madras Presidency, Governor of West Bengal, Minister for Home Affairs of the Indian Union and Chief Minister of Madras state. He was the founder of the Swatantra Party and the first recipient of India's highest civilian award, the Bharat Ratna. Rajaji vehemently opposed the usage of nuclear weapons and was a proponent of world peace and disarmament. He was also nicknamed the Mango of Salem.

Rajagopalachari was born in Thorapalli in the then Salem district and was educated in Central College, Bangalore, and Presidency College, Madras. In 1900 he started a prosperous legal practise. He entered politics and was a member and later President of Salem municipality. He joined the Indian National Congress and participated in the agitations against the Rowlatt Act, the Non-Cooperation movement, the Vaikom Satyagraha and the Civil Disobedience movement. In 1930, he led the Vedaranyam Salt Satyagraha in response to the Dandi March and courted imprisonment. In 1937, Rajaji was elected Chief Minister or Premier of Madras Presidency and served till 1940, when he resigned due to Britain's declaration of war against Germany. He advocated cooperation over Britain's war effort and opposed the Quit India Movement. He favoured talks with Jinnah and the Muslim League and proposed what later came to be known as the "C.R. Formula". In 1946, he was appointed Minister of Industry, Supply, Education and Finance in the interim government. He served as the Governor of West Bengal from 1947 to 1948, Governor-General of India from 1948 to 1950, Union Home Minister from 1951 to 1952 and the Chief Minister of Madras state from 1952 to 1954. He resigned from the Indian National Congress and founded the Swatantra Party, which fought against the Congress in the 1962, 1967 and 1972 elections. Rajaji was instrumental in setting up a united Anti-Congress front in Madras state. This front under C.N. Annadurai captured power in the 1967 elections.

Rajaji was an accomplished writer and made lasting contributions to Indian English literature. He is also credited with composition of the song Kurai Onrum Illai set in Carnatic music. He pioneered temperance and

temple entry movements in India and advocated Dalit upliftment. Rajaji

has been criticized for introducing the compulsory study of Hindi and the Hereditary Education Policy in Tamil Nadu. Critics have often attributed his pre-eminence in politics to his being a favorite of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Rajaji was described by Gandhi as the "keeper of my conscience". Rajagopalachari was born to Chakravarti Iyengar and Singaramma on 10 December 1878 in a devout Iyengar family of Thorapalli in the Madras Presidency. Chakravarti Iyengar was the munsiff of Thorapalli. Rajaji attended school in Hosur and college in Madras and Bangalore. He graduated in arts from Central College, Bangalore, in 1897, and studied law at Presidency College, Madras, in 1899. He started practising as a lawyer in 1900. When in Salem, Rajaji showed keen interest in social and political affairs. Rajaji's interest in public affairs and politics began when he was elected to the government of the city of Salem. In the early 1900s, he was inspired by Indian nationalist Bal Gangadhar Tilak. In 1917, Rajaji was elected Chairman of Salem municipality. As Chairman, he was responsible for the election of the first Dalit (outcaste) member of the Salem municipal government. Rajaji joined the Indian National Congress and became involved in the Indian independence movement. In 1908, he defended Indian freedom fighter P. Varadarajulu Naidu against charges of sedition. He participated in 1919 in the protests against the Rowlatt Act, which indefinitely extended emergency measures passed during World War One. Rajaji was a close friend of Indian nationalist V.O. Chidambaram Pillai, and was highly admired by Annie Besant, a supporter of Indian independence, and C. Vijayaraghavachariar, president of the Indian National Congress in 1920. When Mahatma Gandhi entered the movement for Indian Indepdendance in 1919, Rajaji followed him. He participated in the Non-Cooperation movement and stopped practicing law. In 1921 he was elected to the Congress Working Committee and served as the General Secretary of the party. When the Indian National Congress split in 1923, Rajaji was a member of the Civil Disobedience Enquiry Committee. He supported the old guard and opposed the council entry programme of the Swarajists. Rajaji was one of Gandhi's chief lieutenants during the Vaikom Satyagraha, a movement to improve the lot of Hindu untouchables. It was during this time, that E.V. Ramasamy functioned

as a Congress member under Rajaji's leadership. The two later became

close friends and remained so till the end despite their political

rivalry. In

the early 1930s, Rajaji emerged as one of the foremost leaders of the

Tamil Nadu Congress. When Mahatma Gandhi organized the Dandi march in

1930, Rajaji broke the salt tax at Vedaranyam near Nagapattinam and was sent to prison. Rajaji was subsequently elected President of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee. When

the Government of India Act was enacted in 1935, Rajaji was

instrumental in getting the Indian National Congress to participate in

the general elections. The Indian National Congress was elected to power in the 1937 election for the first time in Madras Presidency (also called Madras Province), a province of British India;

with the exception of the six years when Madras was in a state of

Emergency, it ruled the Presidency until India became independent on 15

August 1947. Rajagopalachari

was the first Chief Minister of Madras Presidency from the Congress

party. Rajagopalachari issued the Temple Entry Authorization and

Indemnity Act 1939 by which restrictions were removed on Dalits and Shanars entering Hindu temples. In the same year, the Meenakshi temple at Madurai was also opened to the Dalits and Shanars. Rajaji also introduced prohibition, and also a sales tax to compensate for the loss of government revenue that resulted from prohibition. Because

of the revenue decline resulting from prohibition the Provincial

Government shut down hundreds of government-run primary schools. Rajaji's

political opponents alleged that this decision deprived many low-caste

and Dalit students of their education. Rajaji's opponents also assigned casteist motives to his government's implementation of Gandhi's Wardha scheme into the education system. Rajagopalachari's

rule is largely remembered however for compulsory introduction of Hindi

in educational institutions, which made him highly unpopular. This measure sparked off widespread anti-Hindi protests,

which led to violence in some places. Over 1,200 men, women and

children were jailed for participating in these protests. Two protesters, Thalamuthu Nadar and Natarasan, were killed. In

1940, Congress ministers resigned protesting the declaration of war on

Germany without their consent, and the Governor took over the reins of

the administration. The unpopular law was eventually repealed by the

Governor of Madras on 21 February 1940. Despite

the numerous shortcomings, Madras under Rajagopalachari was still

regarded as the best administered province in British India. As soon as the Second World War broke out Rajaji resigned as Premier along with other members of his cabinet to protest the declaration of war by the Viceroy of India. Rajaji was arrested in December 1940 in accordance with the Defence of India rules and sentenced to one-year in prison. However, subsequently Rajaji differed in opinion over opposition to British war effort. He opposed the Quit India Movement that Gandhi had initiated in 1942 to pressure the British government to grant independence, and instead advocated dialogue with the British. He reasoned that passivity and neutrality would be harmful to India's interests when the country was threatened with invasion. He also advocated dialogue with the Muslim League, which was demanding the partition of India. He

resigned from the party and the assembly following differences over

resolutions passed by the Madras Congress legislative party and with

the leader of the Madras provincial Congress K. Kamaraj. When the end of the war came in 1945, elections were held in the Madras Presidency in 1946. Kamaraj, the President of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee backed Tanguturi Prakasam as

the Chief Ministerial candidate to prevent Rajaji from coming to power.

Rajaji, however, did not contest the elections and Prakasam was elected. In the last years of the war, Rajaji was instrumental in negotiations between Gandhi and Jinnah. In 1944, he proposed a solution to the Indian Constitutional tangle. In

the same year, Rajaji proposed that 55% be the "absolute majority"

threshold for deciding whether a district should be a part of India or

Pakistan, triggering a huge controversy among nationalists. From

1946 to 1947, Rajaji served as the Minister for Industry, Supply,

Education and Finance in the Interim Government headed by Jawaharlal

Nehru. When India attained independence on 15 August 1947, the British province of Bengal was divided into West Bengal and East Bengal, with West Bengal becoming part of India and East Bengal part of Pakistan. With the support of Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajaji was appointed the first Governor of West Bengal. Rajaji was disliked by Bengalis for his criticism of Subhash Chandra Bose during the 1938 Tripuri Congress session. His appointment was unsuccessfully opposed by Subhash's brother Sarat Chandra Bose. During

his tenure as Governor, Rajaji's priorities were dealing with refugees

and bringing peace and stability in the aftermath of the Calcutta riots. He

declared his commitment to neutrality and justice at a meeting of

Muslim businessmen: "Whatever may be my defects or lapses, let me

assure you that I shall never disfigure my life with any deliberate

acts of injustice to any community whatsoever." Rajaji was also strongly opposed to proposals to include areas from Bihar and Orissa in the province of West Bengal. To

one such proposal by the editor of an important newspaper, he replied:

"I see that you are not able to restrain the policy of agitation over

inter-provincial boundaries. It is easy to yield to current pressure of

opinion and it is difficult to impose on enthusiastic people any policy

of restraint. But I earnestly plead that we should do all we can to

prevent ill-will from hardening into a chronic disorder. We have enough

ill-will and prejudice to cope with. Must we hasten to create further

fissiparous forces?" Rajaji was highly regarded and respected by Chief Minister Prafulla Chandra Ghosh and the state cabinet. From 10 November 1947 to 24 November 1947, Rajaji served as Acting Governor-General of India in the absence of Lord Mountbatten of Burma, who was on leave in England to attend the marriage of Princess Elizabeth to Mountbatten's nephew Prince Philip. Rajaji led a very simple life in the viceregal palace, washing his clothes and polishing his own shoes. Mountbatten

was so impressed with Rajaji's abilities that when he was to leave

India in June 1948 Rajaji was his second choice to succeed him after

Vallabhbhai Patel. Rajaji was eventually chosen as the Governor-General when Nehru disagreed with Mountbatten's first choice, as did Patel himself. Rajaji

was initially hesitant but accepted when Nehru wrote to him, "I hope

you will not disappoint us. We want you to help us in many ways. The

burden on some of us is more than we can carry." Rajaji

served as Governor-General of India from June 1948 to 26 January 1950

and was not only the last Governor-General of India but the only Indian

Governor-General of India. By the end of the year 1949, it was assumed that Rajaji, already Governor-General, would continue as President. Backed by Nehru, Rajaji wanted to stand for the presidential election but later withdrew, due to the opposition of a section of the Indian National Congress mostly made up of North Indians who were concerned about Rajaji's non-participation during the Quit India Movement. In 1950 Rajaji joined the Union Cabinet as Minister without Porfolio, at Nehru's invitation. In 1951 he was put in charge of Home Affairs, serving as the country's Home Minister for nearly 10 months. He warned Nehru about the expansionist designs of China and expressed regret over the Tibet problem, his views being shared with his predecessor Sardar Patel. He

also expressed concern over demands made to establish new

linguistically-based states, arguing that they would generate

differences amongst the people. In the 1952 elections the Congress Party was reduced to a minority in the State Assembly, and the coalition led by the Communist Party of India appeared to be in a better position to form the government. Governor Sri Prakasa nominated

Rajaji to the Legislative Council without the advice of the Council of

Ministers, and appointed Rajagopalchari as unelected Chief Minister. A

further manoeuvre to secure a majority involved luring opposition Members of the Legislative Assembly to

join the party. Nehru was furious and wrote to Rajaji that "the one

thing we must avoid giving is the impression that we stick to office

and we want to keep others out at all costs." Rajaji refused to contest a by-election and remained an unelected member. P.C. Alexander, a former Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra governor, has described these events as a serious constitutional impropriety. During this period Potti Sriramulu called for the creation of a separate Telugu state, to be named Andhra. He went on an unconditional fast until his goal was achieved, dying as a result of the fast. Violent riots broke out in the Telugu areas of Madras State.

Nehru had initially warned that this method of fasting to achieve

administrative or political changes would put an end to democratic

government but after Sriramulu's death, Nehru agreed to the demand for

a separate state of Andhra although he refused to include Madras (now Chennai) city in Andhra. The State of Andhra was formed out of Madras State in

1953, although Rajaji continued to be disengaged from issues

surrounding the new state. Rajaji was accused of not intervening to end

the fast or to provide medical help for Sriramulu, even though the fast

had continued for over 50 days. Prior to his death only one other

person, Jatin Das,

had fasted to death in modern Indian history. In most cases fasters

either gave up, were hospitalised or were arrested and force-fed. Rajaji

removed controls on foodgrains, and introduced a plan in which students

had to go to school in the morning and then to learn the family

vocation, such as carpentry or masonry, after school. It was initially

implemented in the rural areas of the state, and was strongly opposed

as casteist and dubbed Kula Kalvi Thittam (Hereditary Education Policy) by his close friend Periyar,

who vehemently opposed it. This policy was widely criticized by members

of his own party and by political opponents. The controversy led to

Rajagopalachari's resignation in 1954. Although

he claimed to have resigned on grounds of health, the widespread

unpopularity of the government due to the Kula Kalvi Thittam is widely

viewed as the cause. On 15 August 1954, Rajagopalachari became the first recipient of India's highest civilian award, the Bharat Ratna. From

1954 to 1956, Rajaji withdrew from state politics and concentrated on

his literary pursuits. He authored a translation of Kambar's Ramayana

in English and followed it with English translations of the Sanskrit

Ramayana and Mahabharata. In 1956, Rajaji resigned from the Indian National Congress and formed the Congress Reform Committee along with some of his followers. He came to an understanding with his former adversary, Forward Bloc leader U. Muthuramalingam Thevar,

in forming an anti-Congress front. The two parties contested the

elections jointly. In September 1956, the Congress Reform Committee was

renamed the Indian National Democratic Congress. In July 1957, Rajaji

created the Swatantra Party. He attacked the license-permit Raj,

the complex post-World War II bureaucracy introduced by Nehru's

government that regulated business activity, fearing its potential for

corruption and stagnation notwithstanding public support for Nehru's

government. Prominent individuals affiliated with the Swatantra Party included K.M. Munshi, Prof. N.G. Ranga, Minoo Masani, H.M. Patel, V.P. Menon and Maharani Gayatri Devi, Queen of Jaipur. Beginning in the early 1960s the Congress base in Madras state began to erode. The decline was partly due to the entry of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam into

the political arena, and partly due to increasing corruption in the

Congress. Rajaji capitalized on the weakness of his adversary and

strengthened the Swatantra Party. Rajaji criticized India's use of military force against Goa. Referring

to India's acts of international diplomacy, he said that India "has

totally lost the moral power to raise her voice against the use of

military power."

After independence the Indian government had declared in its Constitution that Hindi was to be the official language of

the country, along with English, but because of objections in non-Hindi

areas had allowed for a fifteen-year period for the requirement to be

phased in. From 26 January 1965 onwards, Hindi was to be made the sole

official language of the Indian Union and people in non-Hindi speaking

regions were compelled to learn Hindi. This was vehemently opposed and

just before Republic Day, severe anti-Hindi revolts broke

out in Madras State. Rajaji reversed his earlier position in support of

Hindi and took a strongly anti-Hindi stand in support of the protests. On 17 January 1965, he convened the Madras state Anti-Hindi conference in Tiruchirapalli. He

angrily declared that the Part XVII of the Constitution of India which

declared that Hindi was the official language should "be heaved and

thrown into the Arabian Sea." In

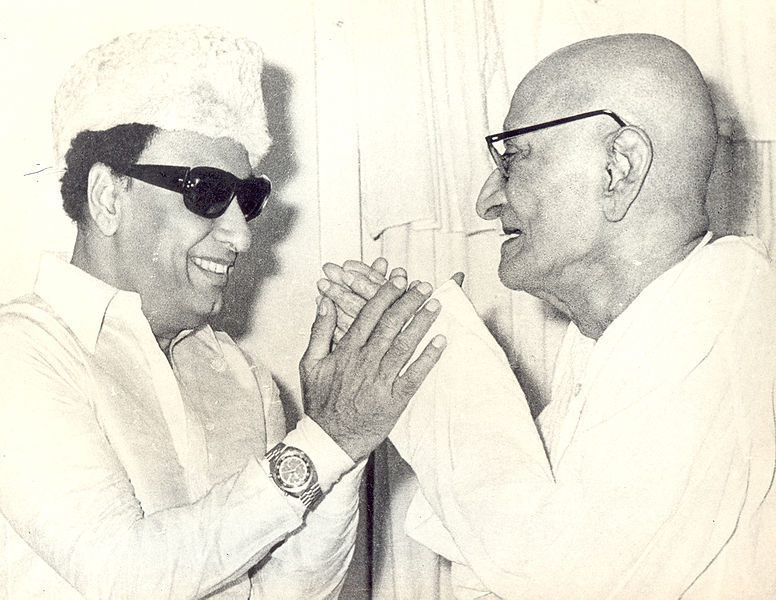

1967 the fourth general elections were held in Madras state. At the age

of 89, Rajaji worked to forge a united opposition to the Indian

National Congress by forming an alliance between the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam,

Swatantra Party and the Forward Bloc. The Congress party was defeated

in its first defeat in Madras in 30 years as the coalition led by

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam was elected to power. C.N. Annadurai became

Chief Minister of Madras state, serving from 1967 to 1969. During this

period he changed the name of the state to Tamil Nadu and introduced

reforms in the administration. Annadurai died in 1969 and was succeeded

by M. Karunanidhi. The Swatantra party also did well in elections in other states and to the Lok Sabha, the directly elected lower house of the Parliament of India.

It won 45 Lok Sabha members in the 1967 general elections and emerged

as the single largest opposition party. It was the principal opposition

party in the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat. It formed a coalition government in Orissa.

It also had a significant presence in Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and

Bihar. In the mid 1960s it won nearly 207 legislative assembly seats

all over India, compared to 153 for the Communists, 149 for the socialists and 115 for the Jan Sangh. But the Party started to disintegrate after the death of Rajaji. It finally merged with Charan Singh's Bharatiya Lok Dal in 1974. In the 1971 Lok Sabha elections, Rajaji organized a united right-wing opposition to Indira Gandhi.

The opposition once again created a major impact as it had during the

1967 elections. However, the Indian National Congress government was

left unscathed and its majority had considerably increased compared to

the 1967 elections, in large part because of the impact of Gandhi's Garibi Hatao anti-poverty program. In his later years, Rajaji was opposed to the repeal of prohibition in

Tamil Nadu by the Karunanidhi government. As a result, the Swatantra

Party withdrew its support for the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam during the

1972 state elections and Rajaji strongly opposed some of the

government's policies. By November 1972, Rajaji's health began to decline. On

17 December 1972, a week after celebrating his 94th birthday, Rajaji

was admitted to General Hospital with uraemia, dehydration and urinary

infection. At hospital, he was visited by Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi, V.R. Nedunchezhiyan, V.V. Giri, Periyar and other state and national leaders. Rajaji's

condition deteriorated in the following days as he frequently lost

consciousness. Rajaji died at 5:44 p.m. on 25 December 1972 at the age

of 94. His son C.R. Narasimhan was beside him at the time of his death reading to him verses from a Hindu holy book.

Rajaji

married Alamelu Mangamma at a very early age. The couple had five

children. His wife died when he was 37 and he took the sole

responsibility of taking care of his children. Rajaji's son C.R. Narasimhan was elected to the Lok Sabha from Krishnagiri in the 1952 and 1957 elections and served as a Member of Parliament for Krishnagiri from 1952 to 1962. He later wrote a biography of Rajaji. Rajaji's daughter Lakshmi was married to Devdas Gandhi, son of Mahatma Gandhi. His grandsons include biographer Rajmohan Gandhi, philosopher Ramchandra Gandhi and former governor of West Bengal Gopalkrishna Gandhi. Rajaji

was an accomplished writer both in his mother tongue Tamil as well as

English. He was the founder of the Salem Literary Society and regularly

participated in its meetings. In 1922, he published a book Siraiyil Tavam (Meditation in jail) which was a day-to-day diary about his first imprisonment from 21 December 1921 to 20 March 1922. In 1916, Rajaji started the Tamil Scientific Terms Society. This society coined new words in Tamil for terms connected to botany, chemistry, physics, astronomy and mathematics. At about the same time, he called for Tamil to be introduced as the medium of instruction in schools. In 1951, Rajaji wrote an abridged retelling of the Mahabharata in English, followed by one of the Ramayana in 1957. Earlier, in 1955, he had translated Kambar's Tamil Ramayana into English. In 1965, he translated the Thirukkural into English. He also wrote books on the Bhagavad Gita, the Upanishads, Socrates, and Marcus Aurelius in English. Rajaji often regarded his literary works as the best service he had rendered to the people. In 1958, he was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award for Tamil for his retelling of the Ramayana - Chakravarti Thirumagan. Apart from his literary works, Rajaji also composed a devotional song Kurai Onrum Illai devoted to Lord Krishna. This song was set to music and is a regular in most Carnatic concerts. Rajaji composed a benediction hymn which was sung by M.S. Subbulakshmi at the United Nations General Assembly in 1967. In 1954 while Richard Nixon, then Vice President of the United States,

was undertaking a nineteen-country Asian trip he was lectured by Rajaji

on the consuming emotional quality of nuclear weapons. Rajaji told

Nixon that it was "wrong to seek the secret of the creation of matter.

It isn't needed for civilian purposes. It is an evil and will destroy

those who [try]'. Nixon apparently did not interpret this as

anti-American, and reported no argument with Rajaji's ominous prophesy. Also,

"... they discussed the spiritual life, particularly reincarantion and

predestination. Nixon filled three pages of notes recording what the

sage had told him, claiming in his memoirs thirty-six years later that

the afternoon 'had such a dramatic effect on me that I used many of his

thoughts in my speeches over the next several years.'" He

was invited to the White House by President Kennedy; perhaps the only

civilian, not in power, ever to be accorded formal state reception. The

two discussed various matters and it is said that the great Indian

statesman tried to impress on the young President the folly of an arms

race - even one which the US could win. At the end of the meeting

President Kennedy remarked "This meeting had the most civilizing

influence on me. Seldom have I heard a case presented with such

precision, clarity and elegance of language". E.M.S. Namboodiripad, a prominent Communist Party leader,

once remarked that Rajaji was the Congress leader he respected the most

despite the fact he was also someone with whom he differed the most. Periyar,

one of Rajaji's foremost political rivals remarked that Rajaji was "a

leader unique and unequalled, who lived and worked for high ideals". On his death, condolences poured in from all corners of the country.