<Back to Index>

- Physicist Albert Abraham Michelson, 1852

- Architect Francis Barry Byrne, 1883

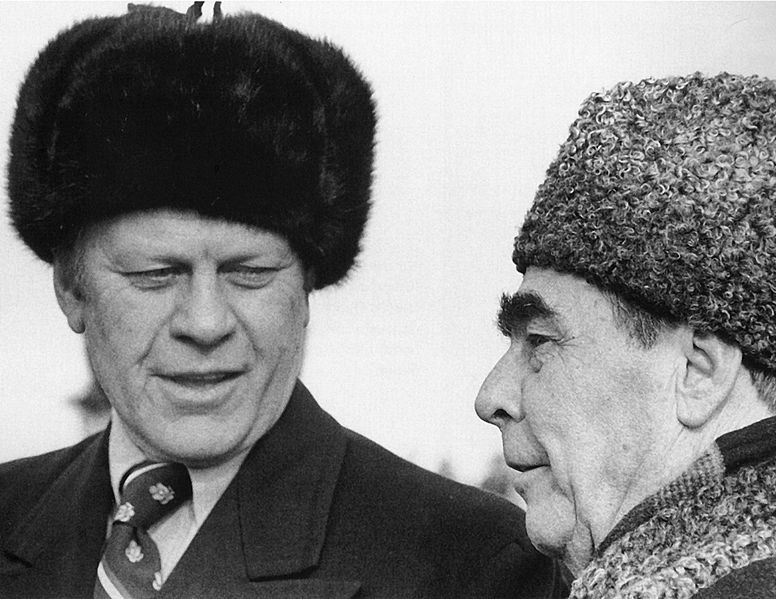

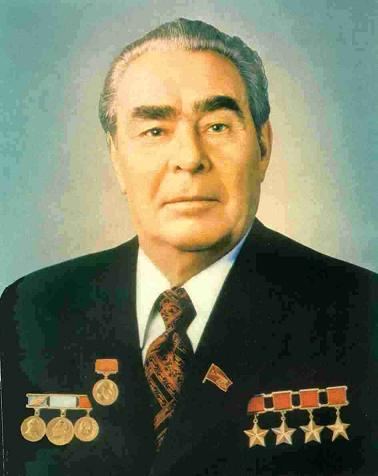

- General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, 1906

PAGE SPONSOR

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (Russian: Леони́д Ильи́ч Бре́жнев; December 19, 1906 – November 10, 1982) was the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, presiding over the country from 1964 until his death in 1982. His eighteen year term as General Secretary was one of the lengthiest, second only to that of Joseph Stalin. During Brezhnev's rule, the global influence of the Soviet Union grew dramatically, in part because of the expansion of the Soviet Military during this time. In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to support the fragile Marxist government located there, a move often criticised by the West. His tenure as leader has often been criticized for marking the beginning of a period of economic stagnation, overlooking serious economic problems which eventually led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Brezhnev was born in Kamenskoe into a Ukrainian workers family. After graduating from the Dniprodzerzhynsk Metallurgical Technicum he became a metallurgical engineer in the iron and steel industry in Ukraine. He joined Komsomol in 1923 and, in 1929, joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, playing an active role in the party's affairs. In 1936, he was drafted into compulsory military service and later became a political commissar in a tank factory. In 1939, he was promoted Party Secretary of Dnipropetrovsk, an important military industrial complex. When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, he was drafted into immediate military service. It was during his service that he met Nikita Khrushchev, whom he would later succeed as General Secretary. He left the army in 1946 with the rank of Major General and was later promoted to First Secretary of the Communist Party in Dnipropetrovsk. In 1950, he became deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the highest legislative body in the country, and in 1952 became a member of the Central Committee.

Brezhnev was appointed to the Presidium (formerly the Politburo) soon

after. He became a Khrushchev protégé in government, but

eventually orchestrated his overthrow and replaced him as General

Secretary in 1964.

As

a leader, Brezhnev was a team player, and took care to consult his

colleagues before acting, but his attempt to govern without significant

economic reforms led to a national decline by the mid 1970s. His rule

marked a significant increase in military expenditures which, at its

height, stood at approximately 30 to 40 percent of the country's GNP,

and an increasingly elderly and ineffective bureaucracy. It was during

this time that the full extent of government corruption became

known, but Brezhnev refused to launch any major corruption

investigations, claiming that no one lived just on their wages. On

November 10, 1982 an ill Brezhnev died, and was quickly succeeded in

his post as General Secretary by Yuri Andropov. Brezhnev was born in Kamenskoe (now Dniprodzerzhynsk in Ukraine), to metal worker Ilya

Yakovlevich Brezhnev and his wife Natalia Denisovna. At different times

during his life, Brezhnev specified his ethnic origin alternately as

either Ukrainian or Russian, opting for the latter as he rose within

the Communist Party. Like many youths in the years after the Russian Revolution of 1917, he received a technical education, at first in land management where he started as a land surveyor and then in metallurgy. He graduated from the Dniprodzerzhynsk Metallurgical Technicum in 1935 and became a metallurgical engineer in the iron and steel industries of eastern Ukraine. He joined the Communist Party youth organization, the Komsomol in 1923 and the Party itself in 1929. In

the years 1935 through 1936, Brezhnev was drafted for compulsory

military service, and after taking courses at a tank school, he served

as a political commissar in

a tank factory. Later in 1936, he became director of the

Dniprodzerzhynsk Metallurgical Technicum (technical college). In 1936,

he was transferred to the regional center of Dnipropetrovsk and, in 1939, he became Party Secretary in Dnipropetrovsk, in charge of the city's important defense industries. As one who survived Stalin's Great Purge of

1937–39, he could gain rapid promotions since the purges opened up many

positions in the senior and middle ranks of the Party and state.

Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in

June 1941, and like most middle-ranking Party officials, Brezhnev was

immediately drafted. He worked to evacuate Dnipropetrovsk's industries

to the east of the Soviet Union before the city fell to the Germans on

26 August and then was assigned as a political commissar. In October, Brezhnev was made deputy of political administration for the Southern Front, with the rank of Brigade-Commissar. When Ukraine was occupied by the Germans in 1942, Brezhnev was sent to the Caucasus as deputy head of political administration of the Transcaucasian Front. In April 1943, he became head of the Political Department of the 18th Army. Later that year, the 18th Army became part of the 1st Ukrainian Front, as the Red Army regained the initiative and advanced westwards through Ukraine. The Front's senior political commissar was Nikita Khrushchev,

who became an important patron of Brezhnev's career. Brezhnev had met

Khrushchev in 1931, shortly after joining the party, and before long he

became Khrushchev's protégé as he continued his rise

through the ranks. At the end of the war in Europe, Brezhnev was chief political commissar of the 4th Ukrainian Front which entered Prague after the German surrender. Brezhnev left the Soviet Army with the rank of Major General in August 1946. He had spent the entire war as a commissar rather than a military commander. After working on reconstruction projects in Ukraine he again became First Secretary in Dnipropetrovsk. In 1950, he became a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union's highest legislative body. Later that year he was appointed Party First Secretary in Moldavia. In 1952, he became a member of the Communist Party's Central Committee and was introduced as a candidate member into the Presidium (formerly the Politburo). Stalin

died in March 1953, and in the reorganization that followed the

Presidium was abolished and a smaller Politburo reconstituted. Although

Brezhnev was not made a Politburo member, he was appointed head of the

Political Directorate of the Army and the Navy with rank of

Lieutenant-General, a very senior position. This was probably due to

the new power of his patron Khrushchev, who had succeeded Stalin as

Party General Secretary. On 7 May 1955, he was made Party First

Secretary of the Communist Party of the Kazakh SSR.

His brief was simple; to make the new lands agriculturally productive;

with this directive, he started the initially successful Virgin Lands Campaign.

Brezhnev was lucky that he was re-called in 1956; the harvest in the

following years proved to be disappointing and would have hurt his

political career if he'd stayed. In

February 1956, Brezhnev returned to Moscow, promoted to candidate

member of the Politburo and assigned control of the defense industry,

the space program, heavy industry, and capital construction. He

was now a senior member of Khrushchev's entourage, and in June 1957, he

backed Khrushchev in his struggle with the Stalinist old guard in the

Party leadership, the so-called "Anti-Party Group". Following the defeat of the old guard, Brezhnev became a full member of the Politburo. Brezhnev became Second Secretary of the Central Committee in 1959, and in May 1960 was promoted to the post of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, making him nominal head of state although the real power resided with

Khrushchev as Party Secretary. In 1962, Brezhnev became an honorary

citizen of Belgrade. Until

about 1962, Khrushchev's position as Party leader was secure, but as

the leader aged he grew more erratic and his performance undermined the

confidence of his fellow leaders. The Soviet Union's mounting economic

problems also increased the pressure on Khrushchev's leadership.

Outwardly, Brezhnev remained loyal to Khrushchev, but he became involved in a 1963 plot to remove the leader from power, possibly playing a leading role. In 1963 also, Brezhnev succeeded Frol Kozlov, another Khrushchev protege, as Secretary of the Central Committee, positioning him as Khrushchev's likely successor. Khrushchev made him deputy party leader in 1964. After returning from Scandinavia and Czechoslovakia, sensing nothing afoot, Khrushchev went on holiday in Pitsunda, near the Black Sea in October 1964. Upon his return, his Presidium officers congratulated him for his work in office. Anastas Mikoyan visited Khrushchev, hinting that he should not be too complacent about his present situation. Vladimir Semichastny, head of the KGB, was a crucial part of the conspiracy, as it was his duty to inform Khrushchev if anyone was plotting against his leadership. Nikolay Ignatov, who had been sacked by Khrushchev, discreetly requested the opinion of several Central Committee members. After some false starts, fellow conspirator Mikhail Suslov phoned Khrushchev on October 12 and requested that he return to Moscow to discuss the state of Soviet agriculture.

Eventually Khrushchev understood what was happening, and said to

Mikoyan, "If it's me who is the question, I won't make a fight of it". While

a minority headed by Mikoyan wanted to remove Khrushchev from the

office of First Secretary but retain him as the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, the majority headed by Brezhnev wanted to remove him from active politics. Brezhnev and Nikolay Podgorny appealed to the Central Committee, blaming Khrushchev for economic failures, and accusing him of voluntarism and immodest behavior. Influenced by the Brezhnev allies, Politburo members voted to remove Khrushchev from office. In

addition, some members of the Central Committee wanted him to undergo

punishment of some kind. But Brezhnev, who had already been assured the

office of the General Secretary, saw little reason to punish his old

mentor further. Brezhnev was appointed Party First Secretary; Alexey Kosygin was appointed Prime Minister, and Mikoyan became head of state. Brezhnev and his companions supported the general party line taken after Joseph Stalin's

death, but felt the Khrushchev reforms had removed much of the Soviet

Union's stability. One of the main reasons for Khrushchev's ouster was

that he continuously overruled other party members. Pravda, a newspaper in the Soviet Union, wrote of new enduring themes such as collective leadership,

scientific planning, consultation with experts, organizational

regularity and the ending of schemes. When Khrushchev left the public

spot light, there was no popular commotion because most Soviet

citizens, including the intelligentsia, anticipated a period of stabilization, steady development of Soviet society and continuing economic growth in the years to come. Early

policy reforms were seen as predictable. In 1964, the plenum of the

Central Committee forbade any single individual to hold the two most

powerful posts of the country (the office of the General Secretary and the Premier). Former Head of the KGB Alexander Shelepin disliked

the new collective leadership reform started under Brezhnev. He made a

bid for the supreme leadership in 1965 by calling for restoration of

"obedience and order". Shelepin failed to gather support in the

Presidium and Brezhnev's position was fairly secure; however, he was

not able to remove Shelepin from office until 1967. Khrushchev

was removed mainly because of his disregard of the collective

leadership. Throughout the Brezhnev era, the Soviet Union was

controlled by a collective leadership, at least through the late 1960s

and 1970s. The consensus within the party was that the collective

leadership prevailed over the supreme leadership of one individual.

T.H. Rigby argued that by the end of the 1960s a stable oligarchic system had

emerged in the Soviet Union, with most power vested around Brezhnev,

Kosygin and Podgorny. While the assessment was true at the time, it

coincided with Brezhnev's strengthening of power by means of an

apparent clash with Central Committee Secretariat Mikhail Suslov. American Henry A. Kissinger, in the 1960s, mistakenly believed Kosygin to be the dominant leader of Soviet foreign policy in

the Politburo. During this period, Brezhnev was gathering enough

support to strengthen his position within Soviet politics. In the

meantime, Kosygin was in charge of economic administration in his role

as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. However Kosygin's position was

weakened when he proposed an economic reform in 1965, which was widely

referred to as the "Kosygin reform" within the Communist Party. The

reform led to a backlash, with Kosygin losing supporters because of the

increasingly anti-reformist stance of many top officials because of the Prague Spring in

1968. His opponents then flocked to Brezhnev, and they happily helped

him in his task of strengthening his position within the Soviet system. Brezhnev

was adept at the politics within the Soviet power structure. He was a

team player and never acted rashy or hastily; unlike Khrushchev, he did

not make decisions without substantial consultation with his

colleagues, and was always willing to hear their opinions. During

the early 1970s, Brezhnev consolidated his domestic position. In 1977,

he forced the retirement of Podgorny and became once again Chairman of

the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union,

making this position equivalent to that of an executive president.

While Kosygin remained Prime Minister until shortly before his death in

1980, Brezhnev was the dominant driving force of the Soviet Union from

the mid-1970s to his death in 1982. Brezhnev 's stabilization policy included ending the liberalizing reforms of Khrushchev, and clamping down on cultural freedom. During

the Khrushchev years Brezhnev had supported the leader's denunciations

of Stalin's arbitrary rule, the rehabilitation of many of the victims

of Stalin's purges, and the cautious liberalization of Soviet

intellectual and cultural policy. But as soon as he became leader,

Brezhnev began to reverse this process, and developed an increasingly

conservative and regressive attitude. The trial of the writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky in 1966 — the first such trials since Stalin's day — marked the reversion to a repressive cultural policy. Under Yuri Andropov the state security service (the KGB) regained much of the power it had enjoyed under Stalin, although there was no return to the purges of the 1930s and 1940s, and Stalin's legacy remained largely discredited among the Soviet intelligentsia. On 22 January 1969, a Soviet Army officer, Viktor Ilyin, tried to assassinate Brezhnev. By

the mid-1970s there were an estimated 10,000 political and religious

prisoners across the Soviet Union. These prisoners lived in grievous

conditions with most of them suffering from malnutrition. Many

prisoners were, according to the Soviet state, mentally unfit and were

hospitalized in mental asylums across

the Soviet Union. The KGB infiltrated most if not all anti-government

organizations under Brezhnev's rule, which ensured that there was

little to no opposition against him or his power base. Brezhnev did

however refrain from the all-out violence seen under the rule of Stalin. Between

the 1960 and 1970, Soviet agriculture output increased by 3 percent

annually. Industry also improved, with the Eighth Five-Years Plan

(1966 – 1970) showing the output of factories and mines increased their

output by 138 percent, compared to 1960. While the politburo became

aggressively anti-reformist, Kosygin was able to convince both Brezhnev and the politburo to leave the reformist communist leader János Kádár of Socialist Hungary alone because of a major economic reform titled New Economic Mechanism (NEM), which granted limited permission for the creation of retail markets in the country. In Socialist Poland, another approach was taken in 1970 under the leadership of Edward Gierek who

believed that the government needed Western loans to facilitate the

rapid growth of heavy industry. The Soviet leadership gave its approval

for this, as the Soviet Union could not afford to maintain its massive

subsidy for the Eastern Bloc in

the form of cheap oil and gas exports. However, the Soviet Union did

not accept all kinds of reforms, and with the Politburo's approval,

Brezhnev gathered the military of the Warsaw Pact to invade Czechoslovakia in 1968. Under Brezhnev, the Politburo abandoned the decentralization experiments of Khrushchev. By 1966, two years after taking power, Brezhnev abolished the Regional Economic Councils, which were organized to manage the regional economies of the Soviet Union. The

Ninth Five-Years Plan delivered a change: for the first time industrial

consumer products out-produced industrial capital goods. Consumer goods

such as watches, furniture and radios were produced in abundance.

However, the Plan still left the bulk of state's investment in

industrial capital goods production. This outcome was not seen as a

positive sign for the future of the Soviet state by the majority of top

party functionaries within the government; by 1975 consumer goods

expanded 9 percent slower than industrial capital goods. This policy

continued despite Brezhnev's reaffirmation of his commitment for the

rapid shift of investment which would satisfy Soviet consumers and lead

to a higher standard of living. This did not happen. From 1928 - 1973 the Soviet Union was growing economically at a phase that would eventually catch up with the United States and Western Europe. This despite the fact that the United States had an advantage; the USSR was hampered by Joseph Stalin's bold policy of collectivization and the Second World War which

had left most of Western USSR in ruins. In 1973 the process of catching

up with the rest of the West came to an abrupt end; with this year

beeing seen by the majority of scholars as the start of the Brezhnev stagnation. The start of the stagnation started simultaneously with the financial crisis in the Western Europe and the US. By the early 1970s the Soviet Union had the world's second largest

industrial capacity and produced more steel, oil, pig-iron, cement and

tractors than any other country. Before

1973 the Soviet economy was expanding at a rate faster, by a small

margin, than that of the United States. The USSR also kept a steady

pace with the economies of Western Europe. Between 1964 - 1973 the Soviet

economy stood at roughly half the output per head of Western Europe and

a little more than one third that of the US. The agricultural policy of Brezhnev reinforced the conventional methods for organizing the collective farms. The central imposition of quotas of output was maintained. Khrushchev's policy of amalgamating farms was prolonged by Brezhnev, because he shared the same belief as Khrushchev that bigger kolkhozes would

increase productivity. Brezhnev pushed for an increase in state

investments in farming, which mounted to an all-time high in the 1970s

to 27 percent of all state investement – this figure did not include

investments in farm equipment. In 1981 alone, 33,000 million American dollars (by contemporary exchange rate) was invested into agriculture. Gross agricultural output by 1980 was 21 percent higher than the average production rate between 1966 – 1970. Cereal crop output

increased by 18 percent. However, improved results were not

encouraging. The usual criterion for assessing agriculture output in

the Soviet Union was the grain harvest. In fact, cereal importation had become a regular phenomenon. When Brezhnev had difficulties sealing commercial trade agreements with the United States, he went elsewhere, such as to Argentina. Trade was necessary because the Soviet Union's domestic production of fodder crops was severely deficient. Another sector which met with mounting problems was the sugar beet harvest which declined by two percent in the 1970s. Brezhnev's way of resolving this was to increase state investment. Politburo member G.I. Voronov had

advocated for several years the division of each farm's work-force into

what he called "links". These "links" would be entrusted with specific

functions, such as to run a farm's dairy unit. His argument was that

the larger the work force, the less responsible they felt. This proposal however had already been turned down by Joseph Stalin in

the 1940s, and been opposed by Khrushchev before and after Stalin's

death. Voronov was also unsuccessful; Brezhnev turned him down, and in

1973 he was removed from the Politburo. Experimentation with "links" was not disallowed on a local basis, with the young Stavropol Region Party Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev experimenting with links in his area. In the meantime, central management of agriculture was otherwise "unimaginative" and "incompetent".

Facing mounting agricultural problems, the Politburo issued a

resolution entitled; "On the Further Development of Specialization and

Concentration of Agricultural Production on the Basis of Inter-Farm

Co-operation and Agro-Industrial Integration". The resolution called

for several kolkhozes in

a given district to combine their objectives in production. In the

meantime, the state's food and agriculture subsidy did not prevent many

farms from operating at a loss: rises in the price of produce were

offset by rises in the cost of oil and other resources. By 1977, oil

cost 84 percent more than it did in the late 1960s. The cost of other

resources had also climbed by the late 1970s. Brezhnev's

answer to these problems was to issue two decrees, one in 1977 and one

in 1981, which called for the expansion of all plots owned by the

Soviet Union to half a hectare. These measures removed large

obstacles for the expansion of Soviet agricultural output. Under

Brezhnev, private plots yielded 30 percent of the national agricultural

production when they only cultivated four percent of agriculture in the

Soviet Union. This was seen by some as proof that de-collectivization

was necessary if Soviet agriculture was ever going to expand. On the

other hand, leading politicians in the Soviet Union withheld from such

drastic measures mainly because of ideological and political interests. The

underlying problems were the growing shortage of skilled labourers, a

wrecked rural culture, the payment of workers in proportion to their

quantity and not their work performance, farm machinery too large for

the small collective farms and the road-less countryside. In the face

of this, Brezhnev could only propose schemes such as large reclamation

and irrigation projects. In

1973 the Soviet economy slowed down and started to lag behind that of

the West because of enormous expenditure on the armed forces and to

little spending on light industry and consumer goods.

Soviet agriculture could not feed the urban population, let alone

provide for the rising standard of living which the government promised

as the fruits of "mature socialism", and on which industrial

productivity depended. One of the most prominent critics of Brezhnev's

economical policies was Mikhail Gorbachev who, when leader, called the economy under Brezhnev's rule "the lowest stage of socialism". With the GNP growth

of the Soviet economy drastically decreasing from the level it held in

the 1950s and 1960s, the country began to lag behind Western Europe and

the United States. The GNP was slowing down to 1 to 2 percent each

year, and with the technology falling farther and farther behind that

of the West, the Soviet Union was facing economic stagnation by the

early 1980s. During Brezhnev's last years of reign, the CIA monitored

the Soviet Union's economic growth, and reported that the Soviet

economy peaked in the 1970s, calculating that it had reached 57 percent

of the American GNP. However, the development gap between the two

nations widened, with the United States growing an average of one

percent over the Soviet Union. The

Eleventh Five-Year Plan of the Soviet Union delivered a disappointing

result, resulting a change in growth from four to five percent. During

the earlier Tenth Five-Year Plan, they had tried to meet the target of

6.1 percent of growth but failed. Brezhnev was able to defer the

economic collapse by trading with Western Europe and the Arab World. However,

the Soviet Union out-produced the United States in heavy industry

during the Brezhnev era. One more galling result of Brezhnev's rule was

that some of the Eastern Bloc economies were more advanced than the Soviet Union. Before 1973, the GDP per head in US dollars increased. Over

the eighteen years Brezhnev ruled the Soviet Union, national income per

head increased by half; however three-quarters of this growth came in

the 1960s and 1970s. There was one-quarter national income per head

growth during the second half of Brezhnev's reign. In

the first half of the Brezhnev period income per head increased by 3.5

percent per annum; slighly less growth than what it had been the

previous years. But this can be explained by the revertion of most of

Khrushchev's policies when Brezhnev came to power. The

consumption per head rose by an estimate of 70% under Brezhnev, but

with three-quarters of this growth happening before 1973 and only

one-quarter in the second half of his reign. At a time when the Soviet economy was in a downward spiral, the standard of living and housing quality improved significantly. Instead of reforming the economy, Brezhnev tried to improve the standard of living in the Soviet Union by extending social benefits, which led to minor increases in public support. The living standard in Soviet Russia had fallen behind that of Soviet Georgia and Estonia under Brezhnev; this led many Russians to believe that Soviet government policies had injured the Russian population. With

the mounting economic problems, skilled workers still had to be paid

more than had been intended, with unskilled labourers having to be

indulged regarding punctuality, conscientiousness and sobriety. The

state usually moved workers from one job to another which ultimately

became an ineradicable feature in Soviet industry; the absence of unemployment in

the Soviet Union led to the state having no serious counter-measures.

Government industries such as factories, mines and offices were staffed

by salaried and waged personnel who put a great effort in not doing

their jobs; this ultimately led to a "work-shy workforce" among Soviet

workers and administrators. The Brezhnev Era saw material improvements for the Soviet citizen, with the Politburo of the CPSU being

given no credit for this. The material improvements in the 1970s, the

cheap provision of consumer goods, food, shelter, clothing, sanitation,

healthcare and transport was taken for granted by the Soviet citizen.

The common Soviet citizen associated Brezhnev's rule more for its

limitation than their actual progress, this led to Brezhnev earning

neither affection nor respect. With most Soviet citizens trying to make

the best of a bad situation, rates of alcoholism, mental illness,

divorce and suicide rose inexorably. While

investments in consumer goods fell below projections, the expansion in

output led to an increase in livings conditions for the ordinary Soviet

civilian. Refrigerators which were owned by only 32 percent of the

population by the early 1970s had grown considerably to a total of 86

percent by the late 1980s and the ownership of colour televisions increased from 51 percent in the early 1970s to 74 percent in the 1980. The material improvements of blue-collar workers

rose considerably; they had higher wages than any professional work

group in the Soviet Union. For example, the wage of a secondary school

teacher in the Soviet Union was only 150 rubles while a bus driver's

wage was 230. While some areas improved during the Brezhnev era,

the majority of civilian services deteriorated, with the physical

environment for a common Soviet falling apart rapidly. Diseases were on

the rise because

of the decaying healthcare system. The living space remained rather

small by western standards, with the common Soviet living on 13.4

square metres. At the same time thousands of Moscow inhabitants were homeless, most of them living in shacks, doorways and parked

trams. Nutrition ceased to improve in the late 1970s, when rationing of

staple food products returned to such cities as Sverdlovsk. The state provided several institutions for daily recreation and annual holidays. Soviet trade unions rewarded hard-working members and their families with beach vacations in Crimea and Georgia. Workers who fulfilled the monthly production quota set

by the Soviet government were honoured by placing their respective

names on the Roll of Honour; the state in the meantime continued to

award badges for all manner of public services, with bemedalled war

veterans being allowed to go to the head of the queues in shops.

Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences had their own special badge and were each provided with a chauffer-driven car. The hierarchy of

honour and privilege in Soviet society paralleled the hierarchy of job

occupations. There was a large enough minority of citizens during the

Brezhnev era who benefited from these perks. These perks did however

not stop the degeneration of Soviet society. Urbanization had led to unemployment in the Soviet agriculture sector, with most of the able workforce leaving villages for the local towns. Another mounting problem in Brezhnev's Soviet was the reduction of the well-educated Soviet labor force. During the Stalin era in the 1930s and 1940s, a common laborer could expect promotion to a white-collar job

if they studied and obeyed Soviet authorities. In Brezhnev's Soviet

this was not the case. Holders of attractive offices clung to them as

long as possible and mere incompetence was never seen as a good reason

to dismiss anyone. Social "rigidification" became a common feature in

Soviet society, in many ways the Soviet society Brezhnev handed to his successor had become "static".

During his eighteen years as supreme Leader of the USSR, Brezhnev's only major foreign policy innovation was the inclusion of détente. However, it did not differ much from the Khrushchev Thaw, a domestic and foreign policy started by Nikita Khrushchev. Historian Robert Service sees

détente simply as a continuation of Khrushchnev's foreign

policy. Despite an increasing tension in East-West relations under

Khrushchnev, relations had generally improved, as evidenced by the Partial Test Ban Treaty, Helsinki Accords and the installation of the telephone line between the White House and the Kremlin.

Brezhnev's détente policy differed from that of Khrushchnev in

two ways. The first was that it was more comprehensive and wide-ranging

in its aims, and included signing agreements on arms control, crisis

prevention, East-West trade, European security, and human rights. The

second part of the policy built on the importance of equalizing the military strength of the United States and

the Soviet Union. Defence spending under Brezhnev between 1965 – 1970

increased by 40 percent, and annual increases continued thereafter.

Fifteen percent of GNP was spent on the military by the time of Brezhnev's death in 1982.

Under Brezhnev, relations with China continued to deteriorate, following the Sino-Soviet split of the early 1960s. In 1969, Soviet and Chinese troops fought a series of clashes along their border on the Ussuri River. The thawing of Sino-American relations beginning

in 1971, however, marked a new phase in international relations. To

prevent the formation of an anti-Soviet U.S.-China alliance, Brezhnev

opened a new round of negotiations with the U.S. In May 1972, President Richard Nixon visited Moscow, and the two leaders signed the SALT I, marking the beginning of the "détente" era. By

the mid 1970s it had become clear that Kissinger's policy of

détente towards the Soviet Union had failed. The détente

had rested on the assumption that a "linkage" of some type could be

found between the two countries, with the US hoping that the signing of SALT I and an increase in Soviet-US trade would stop the aggressive growth of communism in the third world. This did not happen and the Soviet Union started funding the communist guerillas who fought actively against the US during the Vietnam War. The US lost the Vietnam War and at the same time lost many countries to communism in Asia. After Gerald Ford lost the presidential election to Jimmy Carter, American foreign policies became more hostile towards the Soviet Union and the communist world; while at the same time aiming to stop funding for some repressive anti-communist governments the United States supported. While

at first standing for a decrease in all defence initiatives, the later

years of Carter's presidency would increase spending on the US military. In

the 1970s, the Soviet Union reached the peak of its political and

strategic power in relation to the United States. The first SALT Treaty

effectively established parity in nuclear weapons between the two

superpowers, the Helsinki Treaty legitimized Soviet hegemony over Eastern Europe, and the United States defeat in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal weakened

the prestige of the United States. The Soviet Union extended its

diplomatic and political influence in the Middle East and Africa.

After the communist revolution in Afghanistan in 1978, the Afghan civil war started mainly because of authoritarian actions forced upon the populace. With a KGB report claiming that Afghanistan could be taken in a matter of weeks, Brezhnev and several top party officers agreed to full intervention in Afghanistan in the worry that the Soviet Union was losing their influence in Central Asia. Parts of the Soviet military were against full engagement in the country, claiming that the Soviet Union should leave Afghan politics alone. President Carter, following the advice of his National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, denounced the invasion describing it as the "most serious danger to peace since 1945". The US stopped all grain export to the Soviet Union and persuaded US athletes not to enter the 1980 Summer Olympics held in Moscow. The Soviet Union responded by boycotting the 1984 Summer Olympics held in Los Angeles. The first crisis of Brezhnev's regime came in 1968, with the attempt by the Communist leadership in Czechoslovakia, under Alexander Dubček, to liberalize the Communist system (Prague Spring). In July, Brezhnev publicly criticized the Czech leadership as "revisionist" and "anti-Soviet", and in August he orchestrated the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, and Dubček's removal. The invasion led to public protests by dissidents in various Eastern Bloc countries.

Brezhnev's assertion that the Soviet Union had the right to interfere

in the internal affairs of its satellites to "safeguard socialism"

became known as the Brezhnev Doctrine, although it was really a restatement of existing Soviet policy, as Khrushchev had shown in Hungary in 1956. In the aftermath of the invasion, Brezhnev reiterated it in a speech at the Fifth Congress of the Polish United Workers' Party on November 13, 1968: Brezhnev

was not the one pushing hardest for the use of military force when

discussing the situation in Czechoslovakia with the Politburo. Brezhnev

was aware of the dire situation he was in, and if he had abstained or

voted against Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia he may have been

faced with growing turmoil — domestically and in the Eastern Bloc. Archival evidence suggests that Brezhnev was

one of the few who was looking for a temporary compromise with the

reform-friendly Czechoslovak government when their relationsip was at

its brinking point. Significant voices in the Soviet leadership

demanded the re-installation of a so-called 'revolutionary government'. After the military intervention in 1968, Brezhnev met with Czechoslovak reformer Bohumil Simon, then a member of the Politburo of the Czechoslovak Communist Party,

and said; "If I had not voted for Soviet armed assistance to

Czechoslovakia you would not be sitting here today, but quite possibly

i wouldn't either". In the early 1980s a political crisis emerged in Poland with the emergence of the Solidarity mass

movement. By the end of October Solidary had 3 million members, and by

December 9 million. In a public opinion poll done by the Polish

government, 89% of the respondents supported Solidarity. With the Polish leadership split on what to do, the majority did not want to impose martial law, as suggested by Wojciech Jaruzelski. The Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc was unsure how to handle the situation, but Erich Honecker of East Germany pressed

for military action. In a formal letter to Brezhnev Honecker proposed a

joint military measure to control the escalating problems in Poland. A CIA report suggested the Soviet military were mobilizing for an invasion. In 1980 representatives from the Eastern Bloc nations met at the Kremlin to

discusse the Polish situation. Brezhnev eventually concluded that it

would be better to leave the domestic matters of Poland alone for the

time being, re-assuring the Polish delegates that the USSR would intervene only if asked to. With domestic matters escalating out of control in Poland, Wojciech Jaruzelski imposed state of war, the Polish version of martial law, on 12 December 1981. The last years of Brezhnev's rule were marked by a growing personality cult.

He was well known for his love of medals (he received over 200), so in

December 1966, for his 60th birthday, he was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union. Brezhnev received the award, which came with the order of Lenin and the Gold Star, three more times in celebration of his birthdays. On his 70th birthday he was awarded the Marshal of the Soviet Union – the highest military honour in the Soviet Union. After being awarded the medal, he attended the 18th Army Veterans dressed

in a long coat and saying; "Attention, Marshal's coming!". His weakness

for undeserved medals was proven with his badly written memoir about

his military service during World War II. Despite the apparent

weaknesses of his memoirs, they were awarded the Lenin Prize for Literature and were met with critical acclaim by the Soviet press. The book was however followed by two other books, one on the Virgin Lands Campaign. Brezhnev's vanity made him the victim of many political jokes. Nikolai Podgorny warned him of this fact, but Brezhnev replied, "If they are poking fun at me, it means they like me". It is now believed by Western historians and political analysts that the books were written by some of his "court writers". The memoirs treated the little known and minor Battle of Novorossisk as the decisive military theatre of the World War II. Brezhnev's

personality cult was growing outrageously fast at a time when his

health was in decline. His physical condition was deteriorating; he had

become addicted to sleeping pills and

as many other Soviets, began drinking an excessive amount of alcohol,

smoked heavily and had over the years become overweight. From 1973

until his death Brezhnev's central nervous system underwent chronic deterioration and he had several strokes. When receiving the Order of Lenin, Brezhnev walked shakily and fumbled his words. The Minister of Health Yevgeniy Chazov had

to keep doctors by Brezhnev's side at all times, with Brezhnev being

brought back from limbo on several occasions. At this time, most senior

officers of the CPSU wanted to keep him alive, even if such men as Mikhail Suslov, Dmitriy Ustinov and Andrei Gromyko among

others were growing increasingly frustrated with Brezhnev's policies.

However they did not want to risk a new period of domestic turmoil

caused by his death. Brezhnev's health worsened in the winter of 1981–82. In the meantime, the country was governed by Gromyko, Ustinov, Suslov and Yuri Andropov and crucial politburo decisions

was made in his absence. While the politburo was pondering the question

on who would succeed, all signs indicated that the ailing leader was

dying. The choice of the successor would have been influenced by

Suslov, but he died at the age of 79 in January 1982. Andropov took

Suslov's seat in the Central Committee Secretariat; by May it became obvious that Andropov would try to make a bid for the office of the General Secretary. He, with the help of fellow KGB associates,

started circulating rumours that political corruption had become worse

during Brezhnev's tenure as leader in an attempt to create an

environment hostile to Brezhnev in the Politburo. Andropov's actions

showed that he was not afraid of Brezhnev's wrath. Through

spring, summer, autumn 1982 Brezhnev rarely appeared in public. The

official explanation by the CPSU was that Brezhnev was not seriously

ill, while at the same time doctors were surrounding him. When

he was close to death, Brezhnev's mental condition deteriorated to the

point where he could not remember the names of several leading

Politburo members. He was unable to write properly during his dying

days; when asked by Andropov to write a letter of resignation in 1982,

he was unable to do so. On November 10, 1982 Brezhnev suffered a finale attack and died. He was honoured with a state funeral which was followed with a five-day period of nationwide mourning. He was buried in the Kremlin in Red Square. National and international statesmen from

around the globe attended his funeral. His wife and family attended,

with his daughter Galina outraging spectators by not showing up in a

sombre garb. Brezhnev on the other hand was dressed for burial in his

Marshal's uniform along with all his medals.

The Brezhnev stagnation, a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev, was seen as the result of a compilation of factors, including the ongoing "arms race" between the two superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, the decision of the Soviet Union to participate in international trade (thus

abandoning the idea of economic isolation) while ignoring the changes

occurring in Western societies, increasing harshness such as Soviet

tanks rolling in to crush the Prague Spring in 1968, the invasion of Afganistan,

the stifling bureaucracy run by a cadre of increasingly elderly men

running the country, the political corruption, supply bottlenecks, and

other unaddressed structural problems with the economy under Brezhnev's

rule. Social

stagnation domestically was stimulated by the growing demands of

unskilled workers, labour shortages and a decline in productivity and

labour discipline. While Brezhnev, albeit "sporadically", attempted to reform the economy in

the late 1960s and 1970s, he ultimately failed to produce any positive

results. One of these reforms was the reorganization of the Council of Ministries; this led to low unemployment at the price of low productivity and technological stagnation. The economic reform of 1965 was initiated by Aleksei Kosygin, but its origin dates back to Nikita Khrushchev. The Central Committee was not willing to go through with the reform, while at the same time it admitted to economic problems.