<Back to Index>

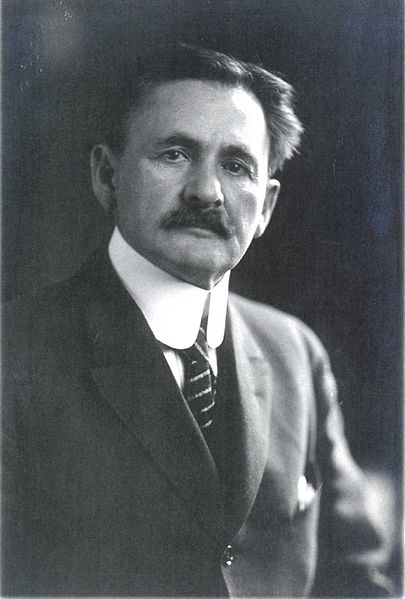

- Physicist Albert Abraham Michelson, 1852

- Architect Francis Barry Byrne, 1883

- General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, 1906

PAGE SPONSOR

Albert Abraham Michelson (December 19, 1852 – May 9, 1931) was an American physicist known for his work on the measurement of the speed of light and especially for the Michelson-Morley experiment. In 1907 he received the Nobel Prize in Physics. He became the first American to receive the Nobel Prize in sciences.

Michelson was born in Strzelno, Provinz Posen in the Kingdom of Prussia (now Poland) into a Jewish family. He moved to the United States with his parents in 1855, when he was two years old. He grew up in the rough mining towns of Murphy's Camp, California and Virginia City, Nevada, where his father was a merchant. He spent his high school years in San Francisco in the home of his aunt, Henriette Levy (née Michelson), who was the mother of author Harriet Lane Levy.

President Ulysses S. Grant awarded Michelson a special appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy in 1869. During his four years as a midshipman at the Academy, Michelson excelled in optics, heat and climatology as well as drawing. After his graduation in 1873 and two years at sea, he returned to the Academy in 1875 to become an instructor in physics and chemistry until 1879. In 1879, he was posted to the Nautical Almanac Office, Washington, to work with Simon Newcomb, but in the following year, he obtained leave of absence to continue his studies in Europe. He visited the Universities of Berlin and Heidelberg, and the Collège de France and École Polytechnique in Paris.

Michelson was fascinated with the sciences and the problem of measuring the speed of light in particular. While at Annapolis, he conducted his first experiments of the speed of light, as part of a class demonstration in 1877. After two years of studies in Europe, he resigned from the Navy in 1881. In 1883 he accepted a position as professor of physics at the Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland, Ohio, and concentrated on developing an improved interferometer. In 1887 he and Edward Morley carried out the famous Michelson-Morley experiment which seemed to rule out the existence of the aether. He later moved on to use astronomical interferometers in the measurement of stellar diameters and in measuring the separations of binary stars.

In 1889 Michelson became a professor at Clark University at Worcester, Massachusetts, and in 1892 was appointed professor and the first head of the department of physics at the newly organized University of Chicago. In 1899, he married Edna Stanton and they raised one son and three daughters.

In 1907, Michelson had the honor of being the first American to receive a Nobel Prize in Physics "for his optical precision instruments and the spectroscopic and metrological investigations carried out with their aid". He also won the Copley Medal in 1907, the Henry Draper Medal in 1916 and the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1923. A crater on the Moon is named after him.

Michelson died in Pasadena, California at the age of 78. The University of Chicago Residence Halls remembered Michelson and his achievements by dedicating Michelson House in his honor. Case Western Reserve has also dedicated a Michelson House to him, and the chemistry academic building at the United States Naval Academy also bears his name. Michelson Laboratory at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake in Ridgecrest, California, is

named after him. There is an interesting display in the publicly

accessible area of the Lab which includes facsimiles of Michelson's

Nobel Prize medal, the prize document, and examples of his diffraction

gratings. As early as 1877, while still serving as an officer in the United States Navy, Michelson started planning a refinement of the rotating-mirror method of Léon Foucault for measuring the speed of light, using improved optics and

a longer baseline. He conducted some preliminary measurements using

largely improvised equipment in 1878 about which time his work came to

the attention of Simon Newcomb, director of the Nautical Almanac Office who

was already advanced in planning his own study. Michelson published his

result of 299,910±50 km/s in 1879 before joining Newcomb in Washington DC to assist with his measurements there. Thus began a long professional collaboration and friendship between the two. Simon Newcomb,

with his more adequately funded project, obtained a value of

299,860±30 km/s, just at the extreme edge of consistency

with Michelson's. Michelson continued to "refine" his method and in

1883 published a measurement of 299,853±60 km/s, rather

closer to that of his mentor. In 1906, a novel electrical method was

used by E.B. Rosa and N.E. Dorsey of the National Bureau of Standards to obtain a value for the speed of light of

299,781±10 km/s. Though this result has subsequently been

shown to be severely biased by the poor electrical standards in use at

the time, it seems to have set a fashion for rather lower measured values. From 1920, Michelson started planning a definitive measurement from the Mount Wilson Observatory, using a baseline to Lookout Mountain, a prominent bump on the south ridge of Mount San Antonio, some 22 miles distant. In 1922, the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey began two years of painstaking measurement of the baseline using the recently available invar tapes. With the baseline length established in 1924, measurements were carried

out over the next two years to obtain the published value of

299,796±4 km/s. Famous

as the measurement is, it was beset by problems, not least of which was

the haze created by the smoke from forest fires which blurred the

mirror image. It is also probable that the intensively detailed work of

the Geodetic Survey, with an estimated error of less than one part in 1 million, was compromised by a shift in the baseline arising from the Santa Barbara earthquake of 29 June 1925, which was an estimated magnitude of 6.3 on the Richter scale. The period after 1927 marked the advent of new measurements of the speed of light using novel electro-optic devices,

all substantially lower than Michelson's 1926 value. Michelson sought

another measurement but this time in an evacuated tube to avoid

difficulties in interpreting the image owing to atmospheric effects. In

1930, he began a collaboration with Francis G. Pease and Fred Pearson to perform a measurement in a 1.6 km tube at Pasadena, California.

Michelson died with only 36 of the 233 measurement series completed and

the experiment was subsequently beset by geological instability and

condensation problems before the result of 299,774±11 km/s,

consistent with the prevailing electro-optic values, was published posthumously in 1935. In 1887 he collaborated with colleague Edward Williams Morley of Western Reserve College, now part of Case Western Reserve University, in the Michelson-Morley experiment. Their experiment for the expected motion of the Earth relative to the aether, the hypothetical medium in which light was supposed to travel, resulted in a null result.

Surprised, Michelson repeated the experiment with greater and greater

precision over the next years, but continued to find no ability to

measure the aether. The Michelson-Morley results were immensely

influential in the physics community, leading Hendrik Lorentz to devise his now-famous Lorentz contraction equations as a means of explaining the null result. There has been some historical controversy over whether Albert Einstein was aware of the Michelson-Morley results when he developed his theory of special relativity,

which pronounced the aether to be "superfluous". Regardless of

Einstein's specific knowledge, the experiment is today considered the

canonical experiment in regards to showing the lack of a detectable

aether.

From 1920 and into 1921 Michelson and Francis G. Pease became the first individuals to measure the diameter of a star other than the Sun. They used an astronomical interferometer at the Mount Wilson Observatory to measure the diameter of the super-giant star Betelgeuse. A periscope arrangement was used to obtain a densified pupil in the interferometer, a method later investigated in detail by Antoine Émile Henry Labeyrie for

use in "Hypertelescopes". The measurement of stellar diameters and the

separations of binary stars took up an increasing amount of Michelson's

life after this.