<Back to Index>

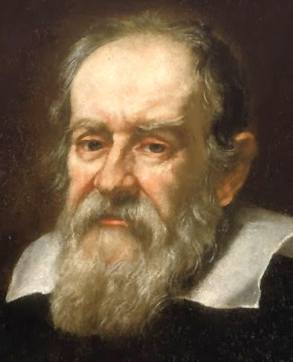

- Physicist, Mathematician, Astronomer and Philosopher Galileo Galilei, 1564

- Painter Charles-André van Loo, 1705

- King of France Louis XV, 1710

Galileo Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations, and support for Copernicanism. Galileo has been called the "father of modern observational astronomy," the "father of modern physics," the "father of science," and "the Father of Modern Science." The

motion of uniformly accelerated objects was studied by Galileo

as the subject of kinematics. His contributions to observational astronomy include the telescopic confirmation of the phases of Venus, the discovery of the four largest satellites of Jupiter (named the Galilean moons in his honour), and the observation and analysis of sunspots. Galileo also worked in applied science and technology, improving compass design. Galileo's

championing of Copernicanism was controversial within his lifetime,

when a large majority of philosophers and astronomers still subscribed

(at least outwardly) to the geocentric view that the Earth is at the centre of the universe. After 1610, when he began publicly supporting the heliocentric view,

which placed the Sun at the centre of the universe, he met with bitter

opposition from some philosophers and clerics, and two of the latter

eventually denounced him to the Roman Inquisition early in 1615. Although he was cleared of any offence at that time, the Catholic Church nevertheless condemned heliocentrism as "false and contrary to Scripture" in February 1616, and

Galileo was warned to abandon his support for it—which he promised to

do. When he later defended his views in his most famous work, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems,

published in 1632, he was tried by the Inquisition, found "vehemently

suspect of heresy," forced to recant, and spent the rest of his life

under house arrest. Galileo was born in Pisa (then part of the Duchy of Florence), Italy, the first of six children of Vincenzo Galilei, a famous lutenist and music theorist, and Giulia Ammannati. Four of their six children survived infancy, and the youngest Michelangelo (or Michelagnolo) became a noted lutenist and composer. Galileo's full name was Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei. At the age of 8, his family moved to Florence, but he was left with Jacopo Borghini for two years. He then was educated in the Camaldolese Monastery at Vallombrosa, 35 km southeast of Florence. Although

he seriously considered the priesthood as a young man, he enrolled for

a medical degree at the University of Pisa at his father's urging. He

did not complete this degree, but instead studied mathematics. In

1589, he was appointed to the chair of mathematics in Pisa. In 1591 his

father died and he was entrusted with the care of his younger brother Michelagnolo. In 1592, he moved to the University of Padua, teaching geometry, mechanics, and astronomy until 1610. During

this period Galileo made significant discoveries in both pure science

(for example, kinematics of motion, and astronomy) and applied science

(for example, strength of materials, improvement of the telescope). Although a genuinely pious Roman Catholic, Galileo fathered three children out of wedlock with Marina Gamba.

They had two daughters, Virginia in 1600 and Livia in 1601, and one

son, Vincenzo, in 1606. Because of their illegitimate birth, their

father considered the girls unmarriageable. Their only worthy

alternative was the religious life. Both girls were sent to the convent

of San Matteo in Arcetri and remained there for the rest of their lives. Virginia took the name Maria Celeste upon entering the convent. She died on 2 April 1634, and is buried with Galileo at the Basilica di Santa Croce di Firenze. Livia took the name Sister Arcangela and was ill for most of her life. Vincenzo was later legitimized and married Sestilia Bocchineri. In

1610 Galileo published an account of his telescopic observations of the

moons of Jupiter, using this observation to argue in favour of the

sun-centered, Copernican theory of the universe against the dominant earth-centered Ptolemaic and

Aristotelian theories. The next year Galileo visited Rome in order to

demonstrate his telescope to the influential philosophers and

mathematicians of the Jesuit Collegio Romano, and to let them see with their own eyes the reality of the four moons of Jupiter. While in Rome he was also made a member of the Accademia dei Lincei. In 1612, opposition arose to the Sun-centered theory of the universe which Galileo supported. In 1614, from the pulpit of the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Father Tommaso Caccini (1574–1648) denounced Galileo's opinions on the motion of the Earth, judging them dangerous and close to heresy. Galileo went to Rome to defend himself against these accusations, but, in 1616, Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino personally handed Galileo an admonition enjoining him neither to advocate nor teach Copernican astronomy. During 1621 and 1622 Galileo wrote his first book, The Assayer (Il Saggiatore), which was approved and published in 1623. In 1630, he returned to Rome to apply for a license to print the Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, published in Florence in 1632. In October of that year, however, he was ordered to appear before the Holy Office in Rome. Following a

papal trial in which he was found vehemently suspect of heresy, Galileo

was placed under house arrest and his movements restricted by the Pope.

From 1634 onward he stayed at his country house at Arcetri, outside of Florence. He went completely blind in 1638 and was suffering from a painful hernia and insomnia,

so he was permitted to travel to Florence for medical advice. He

continued to receive visitors until 1642, when, after suffering fever

and heart palpitations, he died.