<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, 1473

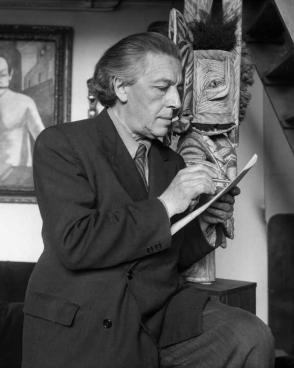

- Writer André Breton, 1896

- Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, 1627

André Breton (February 19, 1896 – September 28, 1966) was a French writer, poet, and surrealist theorist, and is best known as the principal founder of Surrealism. His writings include the Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, in which he defined surrealism as "pure psychic automatism".

Born to a family of modest means in Tinchebray (Orne) in Normandy, he studied medicine and psychiatry. During World War I he worked in a neurological ward in Nantes, where he met the devotee of Alfred Jarry, Jacques Vaché,

whose anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic

tradition influenced Breton considerably. Vaché committed suicide at age 24 and his war-time letters to Breton and others were published in a volume entitled Lettres de guerre (1919), for which Breton wrote four introductory essays. In 1919 Breton founded the review Littérature with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault. He also associated with Dadaist Tristan Tzara. In 1924 he was instrumental to the founding of the Bureau of Surrealist Research. In The Magnetic Fields (Les Champs Magnétiques), a collaboration with Soupault, he put the principle of automatic writing into practice. He published the Surrealist Manifesto during 1924, and was editor of La Révolution surréaliste from 1924. A group coalesced around him - Philippe Soupault, Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard, René Crevel, Michel Leiris, Benjamin Péret, Antonin Artaud, and Robert Desnos. Anxious to combine the themes of personal transformation found in the works of Arthur Rimbaud with the politics of Karl Marx, Breton joined the French Communist Party in

1927, from which he was expelled in 1933. During this time, he survived

mostly off the sale of paintings from his art gallery. Under

Breton's direction, Surrealism became a European movement that

influenced all domains of art, and called into question the origin of

human understanding and human perceptions of things and events. During 1935, there was a conflict between Breton and Ilya Ehrenburg during

the first "International Congress of Writers for the Defense of

Culture" which opened in Paris in June. Breton had been insulted by

Ehrenburg—along with all fellow surrealists—in a pamphlet which said,

among other things, that surrealists were "pederasts".

Breton slapped Ehrenburg several times on the street, which led to

surrealists being expelled from the Congress. Crevel, who according to Salvador Dalí, was "the only serious communist among surrealists" was isolated from Breton and other surrealists, who were unhappy with Crevel because of his homosexuality and upset with communists as a whole. In 1938 Breton accepted a cultural commission from the French government to travel to Mexico. After a conference held at the National Autonomous University of Mexico about surrealism, Breton stated after getting lost in Mexico City (as

no one was waiting for him at the airport) "I don't know why I came

here. Mexico is the most surrealist country in the world". However, visiting Mexico provided the opportunity to meet Leon Trotsky. Breton and other surrealists sought refuge via a long boat ride from Patzcuaro to the town of Erongaricuaro. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo were among the visitors to the hidden community of intellectuals and artists. Together, Breton and Trotsky wrote a manifesto Pour un art révolutionnaire indépendent (published

under the names of Breton and Diego Rivera) calling for a "complete

freedom of art", which was becoming increasingly difficult in the world

situation of the time. In 1939 Breton collaborated with artist Wifredo Lam on the publication of Breton's poem "Fata Morgana", which was illustrated by Lam. Breton was again in the medical corps of the French Army at the start of World War II. The Vichy government banned his writings as "the very negation of the national revolution" and Breton escaped, with the help of the American Varian Fry and Harry Bingham, to the United States and the Caribbean in 1941. Breton came to know Martinican writer Aimé Césaire, and later penned the introduction to the 1947 edition of Césaire's Cahier d'un retour au pays natal. During his exile in New York City he met Elisa, the Chilean woman who would become his third wife. In 1944, he and Elisa traveled to the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec, Canada, where he wrote Arcane 17, a book which expresses his fears of World War II, describes the marvels of the Rocher Percé and the northeastern end of North America, and celebrates his newly found love with Elisa. Breton returned to Paris in 1946, where he opposed French colonialism (for example as a signatory of the Manifesto of the 121 against the Algerian war) and continued, until his death, to foster a second group of surrealists in the form of expositions or reviews (La Brèche, 1961-1965). In 1959, André Breton organized an exhibit in Paris. André Breton died in 1966 at 70 and was buried in the Cimetière des Batignolles in Paris.