<Back to Index>

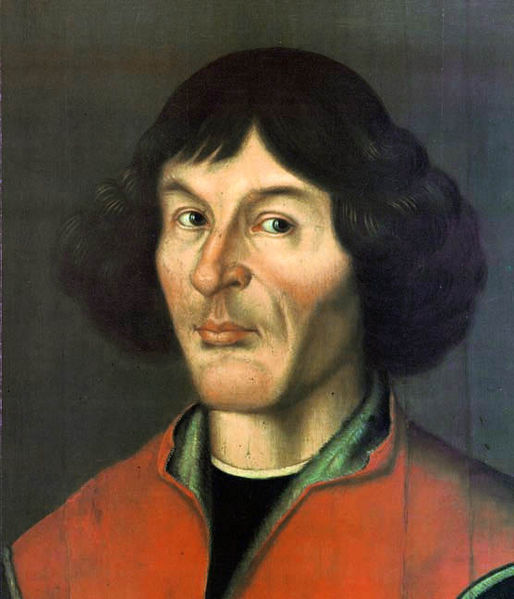

- Astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, 1473

- Writer André Breton, 1896

- Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, 1627

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was the first astronomer to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology, which displaced the Earth from the center of the universe. Copernicus' epochal book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), published just before his death in 1543, is often regarded as the starting point of modern astronomy and the defining epiphany that began the scientific revolution. Among the great polymaths of the Renaissance, Copernicus was a mathematician, astronomer, physician, quadrilingual polyglot, classical scholar, translator, artist, Catholic cleric, jurist, governor, military leader, diplomat and economist. Nicolaus Copernicus was born on 19 February 1473 in the city of Toruń (Thorn) in Prusy Królewskie (Royal Prussia), a prowincja (Region) of the Kingdom of Poland. His father was a merchant from Kraków and

his mother was the daughter of a wealthy Toruń merchant. Nicolaus was

the youngest of four children. His brother Andreas became an Augustinian canon at Frombork (Frauenburg). His sister Barbara, named after her mother, became a Benedictine nun. His sister Katharina married Barthel Gertner, a businessman and city councilor. Copernicus never married or had children. The father’s family can be traced to a village in Silesia near Nysa (Neiße). The village's name has been variously spelled Kopernik, Köppernig, Köppernick, and today Koperniki.

In the 14th century, members of the family began moving to various

other Silesian cities, to the Polish capital, Kraków (1367), and

to Toruń (1400). The father, likely the son of Jan, came from the

Kraków line. Nicolaus was named after his father, who appears in records for the first time as a well-to-do Roman Catholic merchant who dealt in copper, selling it mostly in Danzig (Gdańsk). He moved from Kraków to Toruń around 1458. Toruń, situated on the Vistula River, was at that time embroiled in the Thirteen Years' War (1454–66), in which the Kingdom of Poland, allied with Pomeranian cities, fought the Teutonic Order over

control of the region. The father was actively engaged in the politics

of the day, and he supported Poland and the cities against the Teutonic

Order. In 1454 he mediated negotiations between Poland’s Cardinal Zbigniew Oleśnicki and the Pomeranian cities over repayment of war loans. In the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), the Teutonic Order formally relinquished all claims to Royal Prussia, which then remained a Region of Poland for the next 300 years. The

father married Barbara Watzenrode, the astronomer's mother, between

1461 and 1464. He died sometime between 1483 and 1485. Upon the

father’s death, young Nicolaus’ maternal uncle, Lucas Watzenrode the Younger (1447–1512), took the boy under his protection and saw to his education and career. Nicolaus’ mother, Barbara Watzenrode, was the daughter of Lucas Watzenrode the Elder and his wife Katherine (née Modlibóg). The Watzenrodes, who were Roman Catholic, had

come from the Świdnica region of Silesia and had settled in Toruń after 1360, becoming prominent members of the city’s patrician class.

Through the Watzenrodes' extensive family relationships by marriage,

they were related to wealthy families of Toruń, Danzig and Elbląg (Elbing), and to the prominent Czapski, Działyński, Konopacki and Kościelecki noble families. The

Modlibógs (literally, in Polish, "Pray to God") were a prominent

Roman Catholic Polish family who had been well known in Poland's

history since 1271. Lucas

and Katherine had three children: Lucas Watzenrode the Younger, who

would become Copernicus' patron; Barbara, the astronomer's mother; and

Christina, who in 1459 married the merchant and mayor of Toruń,

Tiedeman von Allen. Lucas Watzenrode the Elder was

well-regarded in Toruń as a devout man and honest merchant, and he was

active politically. He was a decided opponent of the Teutonic Knights

and an ally of Polish King Kazimierz IV Jagiellon. In 1453 he was the delegate from Toruń at the Grudziądz (Graudenz)

conference that planned the Pomeranian cities’ alliance with Kazimierz

and their subsequent war against the Teutonic Knights. During the Thirteen Years' War that

ensued the following year, he actively supported the war effort with

substantial monetary subsidies, with political activity in Toruń and

Danzig, and by personally fighting in battles at Łasin and Marienburg. He died in 1462. Lucas Watzenrode the Younger, the astronomer's maternal uncle and patron, was educated at the Kraków Academy (now Jagiellonian University) and at the universities of Cologne and Bologna. He was a bitter opponent of the Teutonic Order and its Grand Master. In 1489 Watzenrode was elected Bishop of Warmia against

the wishes of King Kazimierz IV, who had hoped to install his own son

in that seat. As a result, Watzenrode quarreled with the King until

Kazimierz’s death three years later. Watzenrode was then able to form close relations with three successive Polish monarchs—Jan Olbracht, Alexander Jagiellon, and Zygmunt I.

He was a friend and key advisor to each ruler, and his influence

greatly strengthened the ties between Warmia and Poland proper. Watzenrode

came to be considered the most powerful man in Warmia, and his wealth,

connections and influence allowed him to secure Copernicus’ education

and career as a canon at Frombork (Frauenberg) Cathedral. Copernicus spoke Latin, Polish, and German with equal fluency. He also spoke Greek and Italian. The vast majority of Copernicus’ surviving works are in Latin, which in his lifetime was the universal language of academia.

Latin was also the official language of the Roman Catholic Church and

of Poland's royal court, and thus all of Copernicus’ correspondence

with the Church and with Polish leaders was in Latin. A German-language correspondence between Copernicus and Duke Albert of Prussia has survived. Copernicus'

uncle seems first to have sent him to the St. John's School at Toruń

where he himself had been a master. Later the boy attended the

Cathedral School at Włocławek, up the Vistula River from Toruń, which prepared pupils for entrance to the Kraków Academy, in Poland's capital. In 1491 Copernicus enrolled in the Kraków Academy (now Jagiellonian University). It was there that he probably first encountered astronomy with Professor Albert Brudzewski.

Astronomy soon fascinated him, and he began collecting a large library

on the subject. Copernicus' library would later be carried off as war

booty by the Swedes during the Deluge; it is now at the Uppsala University Library. After four years in Kraków, followed by a brief stay back home in Toruń, Copernicus went to study law and medicine at the universities of Bologna and Padua. Copernicus' uncle, Lucas Watzenrode the Younger, financed his education. Copernicus, however, while studying canon and civil law at Bologna, met the famous astronomer, Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara.

Copernicus attended Novara's lectures and became his disciple and

assistant. Copernicus published his first astronomical observations,

made with Novara in 1497, in De revolutionibus. In 1497 Watzenrode was ordained Bishop of Warmia, and Copernicus was named a canon at Frombork Cathedral. But Copernicus remained in Italy, where he attended the Jubilee of 1500. He also went to Rome, where he observed a lunar eclipse and gave lectures in astronomy and mathematics. Copernicus

returned to Frombork in 1501. As soon as he arrived, he obtained

permission to complete his studies in Padua, where he studied medicine with Guarico and Girolamo Fracastoro, and at Ferrara, where he received a doctorate in canon law on 31 May 1503. On 10 January 1503, before obtaining his doctorate in canon law at Ferrara, Copernicus had received a sinecure at the Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross in Wrocław (Breslau), Silesia, Bohemia. In

1503, having completed all his studies in Italy, 30-year-old Copernicus

returned to Warmia, where he would live out the remaining 40 years of

his life. The Prince-Bishopric of Warmia enjoyed substantial autonomy, with its own diet, army, monetary unit (the same as in the other parts of Royal Prussia) and treasury. From

1503 to 1510, or perhaps till his uncle's death (29 March 1512),

Copernicus was his personal secretary and physician and resided in the

Bishop's castle at Lidzbark Warmiński (Heilsberg).

It is there that he began work on his heliocentric theory. In his

official capacity, he took part in nearly all his uncle's political,

ecclesiastic and administrative-economic duties. From the beginning of

1504, Copernicus accompanied Watzenrode to sessions of the Royal

Prussian diet held at Malbork and Elbląg. In 1504–12 Copernicus made numerous

journeys as part of his uncle's retinue—in 1504, to Toruń and Gdańsk

(Danzig), to a session of the Royal Prussian Council in the presence of

Poland's King Alexander Jagiellon;

to sessions of the Prussian diet at Malbork (1506), Elbląg (1507) and

Sztum (1512); and he may have attended a Poznań session (1510) and the

coronation of Poland's King Sigismund I the Old in Kraków (1507). Watzenrode's itinerary suggests that in spring 1509 Copernicus may have attended the Kraków sejm. It was probably on the latter occasion, in Kraków, that Copernicus submitted for printing at Jan Haller's press his translation, from Greek to Latin, of a collection, by the 7th-century Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocatta, of 85 brief poems called

Epistles, or letters, supposed to have passed between various

characters in a Greek story. With his translation, Copernicus declared

himself on the side of the humanists in the struggle over the question whether Greek literature should be revived. Some

time before 1514, Copernicus wrote an initial outline of his

heliocentric theory known only from later transcripts, by the title

(perhaps given to it by a copyist), Nicolai Copernici de hypothesibus motuum coelestium a se constitutis commentariolus—commonly referred to as the Commentariolus.

It was a succinct theoretical description of the world's heliocentric

mechanism, without mathematical apparatus, and differed in some

important details of geometric construction from De revolutionibus; but it was already based on the same assumptions regarding Earth's triple motions. In 1510 or 1512 Copernicus moved to Frombork, a town to the northwest at the Vistula Lagoon on the Baltic Sea coast. There, in April 1512, he participated in the election of Fabian of Lossainen as Prince-Bishop of Warmia.

It was only in early June 1512 that the chapter gave Copernicus an

"external curia"—a house outside the defensive walls of the cathedral

mount. In 1514 he purchased the northwestern tower within the walls of

the Frombork stronghold. He would maintain both these residences to the

end of his life, despite the devastation of the chapter's buildings by

a raid against Frombork carried out by the Teutonic Order in January

1520, during which Copernicus' astronomical instruments were probably

destroyed. At Frombork Copernicus conducted over half of his more than 60 registered astronomical observations. During 1516–21, Copernicus resided at Olsztyn Castle as economic administrator of Warmia, including Olsztyn (Allenstein) and Pieniężno (Mehlsack). While there, he wrote a manuscript, Locationes mansorum desertorum (Locations of Deserted Fiefs). When Olsztyn was besieged by the Teutonic Knights during the Polish–Teutonic War (1519–21),

Copernicus was in charge of the defense of Olsztyn and Warmia by the

Royal Polish forces. He also participated in the peace negotiations. Copernicus worked for years with the Royal Prussian diet, and with Duke Albert of Prussia (against whom Copernicus had defended Warmia in the Polish-Teutonic War), and advised King Sigismund on monetary reform.

He participated in discussions in the East Prussian diet about coinage

reform in the Prussian countries. One question that concerned the diet

was who had the right to mint coin. The matter required diplomacy, but was resolved successfully. Some difficulties were caused by political upheavals in Prussia at the time, including the establishment of the Duchy of Prussia as a Protestant state in 1525. In 1526 Copernicus wrote a study on the value of money, Monetae cudendae ratio. In it he formulated an early iteration of the theory, now called Gresham's Law, that "bad" (debased) coinage drives "good" (un-debased) coinage out of circulation—70 years before Thomas Gresham. Following the death of Prince-Bishop of Warmia Mauritius Ferber (1

July 1537), Copernicus participated in the election of his successor,

Johannes Dantiscus (20 September 1537). Copernicus was one of four

candidates for the post, written in at the initiative of Tiedemann Giese; but his candidacy was actually pro forma, since Dantiscus had earlier been named coadjutor bishop to Ferber. At

first Copernicus maintained friendly relations with the new

Prince-Bishop, assisting him medically in spring 1538 and accompanying

him that summer on an inspection tour of Chapter holdings. But that

autumn, their friendship was strained by suspicions over Copernicus'

housekeeper, Anna Schilling, whom Dantiscus removed from Frombork in

1539. In

his younger days, Copernicus the physician had treated his uncle,

brother and other chapter members. In later years he was called upon to

attend the elderly bishops who in turn occupied the see of

Warmia—Mauritius Ferber and Johannes Dantiscus—and, in 1539, his old

friend Tiedemann Giese, Bishop of Chełmno (Kulm).

In treating such important patients, he sometimes sought consultations

from other physicians, including the physician to Duke Albert and, by

letter, the Polish Royal Physician. In the spring of 1541, Duke Albert summoned Copernicus to Königsberg to attend the Duke's counselor, George von Kunheim,

who had fallen seriously ill, and for whom the Prussian doctors seemed

unable to do anything. Copernicus went willingly; he had met von

Kunheim during negotiations over reform of the coinage. And Copernicus

had come to feel that Albert himself was not such a bad person; the two

had many intellectual interests in common. The Chapter readily gave

Copernicus permission to go, as it wished to remain on good terms with

the Duke, despite his Lutheran faith.

In about a month the patient recovered, and Copernicus returned to

Frombork. For a time, he continued to receive reports on von Kunheim's

condition, and to send him medical advice by letter.

Some time before 1514 Copernicus made available to friends his "Commentariolus" ("Little Commentary"), a forty-page manuscript describing his ideas about the heliocentric hypothesis. It

contained seven basic assumptions. Thereafter he continued gathering

data for a more detailed work. About 1532 Copernicus had basically

completed his work on the manuscript of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium;

but despite urging by his closest friends, he resisted openly

publishing his views, not wishing—as he confessed—to risk the scorn "to

which he would expose himself on account of the novelty and

incomprehensibility of his theses." Copernicus died in Frauenburg (Frombork) on 24 May 1543. Legend has it that the first printed copy of De revolutionibus was

placed in his hands on the very day that he died, allowing him to take

farewell of his life's work. He is reputed to have awoken from a stroke-induced coma, looked at his book, and then died peacefully. Copernicus was reportedly buried in Frombork Cathedral,

where archeologists for over two centuries searched in vain for his

remains. Efforts to locate the remains in 1802, 1909, 1939 and 2004 had

come to nought. In August 2005, however, a team led by Jerzy Gąssowski,

head of an archaeology and anthropology institute in Pułtusk, after scanning beneath the cathedral floor, discovered what they believed to be Copernicus' remains. The

find came after a year of searching, and the discovery was announced

only after further research, on November 3, 2008. Gąssowski said he was

"almost 100 percent sure it is Copernicus." Forensic

expert

Capt. Dariusz Zajdel of the Polish Police Central Forensic Laboratory

used the skull to reconstruct a face that closely resembled the

features—including a broken nose and a scar above the left eye—on a

Copernicus self-portrait. The expert also determined that the skull

belonged to a man who had died around age 70—Copernicus' age at the

time of his death. The grave was

in poor condition, and not all the remains of the skeleton were found;

missing, among other things, was the lower jaw. The

DNA from the bones found in the grave matched hair samples taken from a

book owned by Copernicus which was kept at the library of the University of Uppsala in Sweden.

In 1533, Johann Albrecht Widmannstetter delivered a series of lectures in Rome outlining Copernicus' theory. Pope Clement VII and several Catholic cardinals heard the lectures and were interested in the theory. Copernicus was still working on De revolutionibus orbium coelestium when in 1539 Georg Joachim Rheticus, a Wittenberg mathematician, arrived in Frombork. Philipp Melanchthon, a close theological ally of Martin Luther,

had arranged for Rheticus to visit several astronomers and study with

them. Rheticus became Copernicus' pupil, staying with him for two years

and writing a book, Narratio prima (First Account), outlining the essence of Copernicus' theory. In 1542 Rheticus published a treatise on trigonometry by Copernicus (later included in the second book of De revolutionibus). Under

strong pressure from Rheticus, and having seen the favorable first

general reception of his work, Copernicus finally agreed to give De revolutionibus to his close friend, Tiedemann Giese, bishop of Chełmno (Kulm), to be delivered to Rheticus for printing by Johannes Petreius at Nuremberg (Nürnberg).

While Rheticus initially supervised the printing, he had to leave

Nuremberg before it was completed, and he handed over the task of

supervising the rest of the printing to a Lutheran theologian, Andreas Osiander. Osiander

added an unauthorised and unsigned preface, defending the work against

those who might be offended by the novel hypotheses.