<Back to Index>

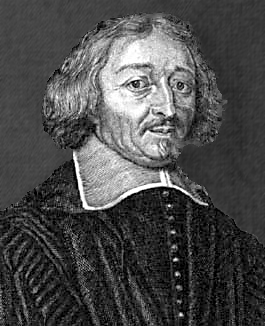

- Mathematician Jean-Baptiste Morin, 1583

- Composer Georg Friedrich Händel, 1685

- First President of the Republic of Estonia Konstantin Päts, 1874

Jean-Baptiste Morin (February 23, 1583—November 6, 1656), also known by his Latin pseudonym as Morinus, was a French mathematician, astrologer, and astronomer.

Born in Villefranche-sur-Saône, in the Beaujolais, he began studying philosophy at Aix-en-Provence at the age of 16. He studied medicine at Avignon in 1611 and received his medical degree two years later. He was employed by the Bishop of Boulogne from 1613 to 1621 and was sent to Germany and Hungary during this time. He served the bishop as an astrologer and also visited mines and studied metals. He subsequently worked for the Duke of Luxembourg until 1629. Morin published a defense of Aristotle in 1624. He also worked in the field of optics, and continued to study in astrology. He worked with Pierre Gassendi on observational astronomy.

In 1630, Morin was appointed professor of mathematics at the Collège Royal, a post he held until his death.

A firm believer of the idea that the Earth remained fixed in space, Morin is best known for being opponent of Galileo and the latter's ideas. He continued his attacks after the Trial of Galileo. Morin seems to have been a rather contentious figure, as he also attacked Descartes' ideas after meeting the philosopher in 1638. These disputes isolated Morin from the scientific community at large. Morin believed that improved methods of solving spherical triangles had to be found and that better lunar tables were needed. Morin attempted to solve the longitude problem. In 1634, he proposed his solution, based on measuring absolute time by the position of the Moon relative to the stars. His method was a variation of the lunar distance method first put forward by Johann Werner in 1514. Morin added some improvements to this method, such as better scientific instruments and taking lunar parallax into account. Morin did not believe that Gemma Frisius' transporting

clock method for calculating out longitude would work. Morin,

unfailingly irascible, remarked, "I do not know if the Devil will

succeed in making a longitude timekeeper but it is folly for man to

try." A prize was to be awarded, so a committee was set up by Richelieu to evaluate Morin's proposal. Serving on this committee were Étienne Pascal, Claude Mydorge, and Pierre Hérigone.

The committee remained in dispute with Morin for the five years after

he made his proposal. Morin refused to listen to objections to his

proposal, which was considered impractical. In his attempts to convince

the committee members, Morin proposed that an observatory be set up in order to provide accurate lunar data. He wrangled with the committee for five years. In 1645, Cardinal Mazarin, Richelieu's successor, awarded Morin a pension of 2,000 livres for his work on the longitude problem. Perhaps most famous for his work as an astrologer, towards the end of his life Morin completed Astrologia Gallica ("French

Astrology"), a treatise which he did not live to see in print. The 26

books of intricate, complex, Latin text were published at the Hague in

1661 as one thick folio 850 pages long. The work covers natal, judicial, mundane, electional and meteorological astrology,

and parts that are most concerned with astrological techniques (as

compared to theological discussion on which they are based) have been

translated or paraphrased into French, Spanish, German, and English. At

least among English-speaking astrologers, Morin is known as having been

particularly concerned with prediction through methodical extrapolation

of what is promised in the natal chart. His techniques were directions, solar and lunar return, and he regarded transits a subsidiary technique though one key to accurate timing of events nonetheless. Morin challenged much of classical astrological theory, including the astrology of Ptolemy,

in an attempt to present a solid set of tools while rendering reasons

for and against particular techniques, some of which may be considered

crucial to many astrologers before and during Morin’s lifetime. At the

same time, Morin vested himself heavily in promoting in mundo directions, a technique largely based on the work of Regiomontanus that

became available thanks to then-recent advancement in mathematics. In

his work, Morin provides examples of successful delineation of events

that otherwise could not be delineated with the same relative degree of

certainty. Morin’s life has been that of trial and tribulation by his own testament. He died in Paris of natural causes at 73 years of age.