<Back to Index>

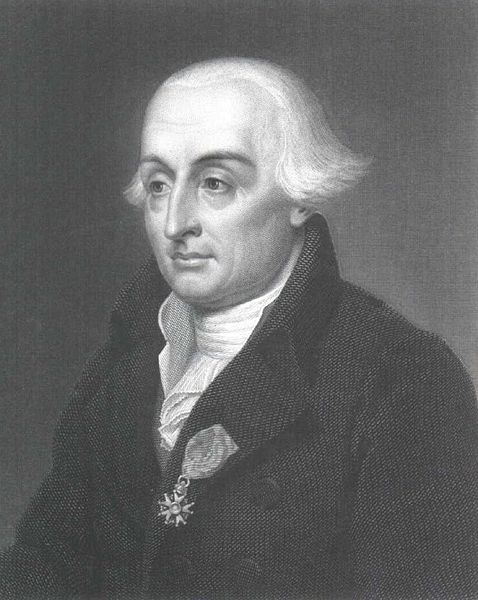

- Mathematician Joseph-Louis, Comte de Lagrange, 1736

- Painter Govert Flinck, 1615

- President of the Philippines Corazón Aquino, 1933

Joseph-Louis Lagrange (25 January 1736 – 10 April 1813), born Giuseppe Lodovico (Luigi) Lagrangia, was an Italian-born mathematician and astronomer, who lived part of his life in Prussia and part in France, making significant contributions to all fields of analysis, to number theory, and to classical and celestial mechanics. On the recommendation of Euler and D'Alembert, in 1766 Lagrange succeeded Euler as the director of mathematics at the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, where he stayed for over twenty years, producing a large body of work and winning several prizes of the French Academy of Sciences. Lagrange's treatise on analytical mechanics (Mécanique Analytique,

4. ed., 2 vols. Paris: Gauthier-Villars et fils, 1888-89), written in

Berlin and first published in 1788, offered the most comprehensive

treatment of classical mechanics since Newton and formed a basis for the development of mathematical physics in the nineteenth century. In 1787, at age 51, he moved

from Berlin to France and became a member of the French Academy, and he

remained in France until the end of his life. Therefore, Lagrange is

alternatively considered a French and an Italian scientist. Lagrange survived the French Revolution and became the first professor of analysis at the École Polytechnique upon its opening in 1794. Napoleon named Lagrange to the Legion of Honour and made him a Count of the Empire in 1808. He is buried in the Panthéon. Lagrange is one of the founders of calculus of variations. He wrote several letters

to Leonhard Euler between 1754 and 1756 describing his results. He outlined his "δ-algorithm", leading to the Euler–Lagrange equations of variational calculus and considerably simplifying Euler's earlier analysis. In 1758, with the aid of his pupils, Lagrange established a society, which was subsequently incorporated as the Turin Academy of Sciences, and most of his early writings are to be found in the five volumes of its transactions, usually known as the Miscellanea Taurinensia.

The next work he produced was in 1764 on the libration of the Moon, and an explanation as to why the same face was always turned to the earth, a problem which he treated by the aid of virtual work. Already in 1756 Euler, with support from Maupertuis, made an attempt to bring Lagrange to the Berlin Academy. Later, D'Alambert interfered on Lagrange's behalf withFrederick of Prussia and

wrote to Lagrange asking him to leave Turin for a considerably more

prestigious position in Berlin. Lagrange turned down both offers,

responding in 1765 that In 1766 Euler left Berlin for Saint Petersburg,

and Frederick wrote to Lagrange expressing the wish of "the greatest

king in Europe" to have "the greatest mathematician in Europe" resident

at his court. Lagrange was finally persuaded and he spent the next

twenty years in Prussia,

where he produced not only the long series of papers published in the

Berlin and Turin transactions, but his monumental work, the Mécanique analytique.

His residence at Berlin commenced with an unfortunate mistake. Finding

most of his colleagues married, and assured by their wives that it was

the only way to be happy, he married; his wife soon died, but the union

was not a happy one. In 1786, Frederick died, and Lagrange, who had found the climate of Berlin trying, gladly accepted the offer of Louis XVI to migrate to Paris. He received similar invitations from Spain and Naples. He became

a member of the French Academy of Sciences, which later became part of the National Institute. At the beginning of his residence in Paris he was seized with an attack of the melancholy. Curiosity as to the results of the French revolution first stirred him out of his lethargy, a curiosity which soon turned to alarm as the revolution developed. It

was about the same time, 1792, that the unaccountable sadness of his

life and his timidity moved the compassion of a young girl who insisted

on marrying him, and proved a devoted wife to whom he became warmly

attached. Although the decree of October 1793 that ordered all

foreigners to leave France specifically exempted him by name, he was

preparing to escape when he was offered the presidency of the

commission for the reform of weights and measures. The choice of the

units finally selected was largely due to him, and it was mainly owing

to his influence that the decimal subdivision was accepted by the

commission of 1799. In 1795, Lagrange was one of the founding members

of the Bureau des Longitudes. In 1795, Lagrange was appointed to a mathematical chair at the newly-established École normale,

which enjoyed only a brief existence of four months. Lagrange was appointed professor of the École Polytechnique in

1794; and his lectures there are described by mathematicians who had

the good fortune to be able to attend them, as almost perfect both in

form and matter. On the other hand, Fourier, who attended his lectures in 1795, wrote: In 1810, Lagrange commenced a thorough revision of the Mécanique analytique, but he was able to complete only about two-thirds of it before his death in 1813. He was buried that same year in the Panthéon in Paris. The French inscription on his tomb there reads: JOSEPH

LOUIS LAGRANGE. Senator. Count of the Empire. Grand Officer of the

Legion of Honour. Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Réunion.

Member of the Instit

ute and the Bureau of Longitude. Born in Turin on 25 January 1736. Died in Paris on 10 April 1813.