<Back to Index>

- Geographer Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d' Anville, 1697

- Poet Luis de Góngora y Argote, 1561

- 6th President of the United States John Quincy Adams, 1767

His passion for geographical research displayed itself from early years: at the age of twelve he was already amusing himself by drawing maps for Latin authors. Later, his friendship with the antiquarian, Abbé Longuerue, greatly aided his studies.

His first serious map, that of Ancient Greece, was published when he was fifteen. At the age of twenty-two, he was appointed one the king's geographers, and began to attract the attention of first authorities. D'Anville's studies embraced everything of geographical nature in the world's literature, as far as he could muster it: for this purpose, he not only searched ancient and modern historians, travelers and narrators of every description, but also poets, orators and philosophers. One of his cherished subjects was to reform geography by putting an end to the blind copying of older maps, by testing the commonly accepted positions of places through a rigorous examination of all the descriptive authority, and by excluding from cartography every name inadequately supported. Vast spaces, which had before been bordered with countries and cities, were thus suddenly reduced mostly to a blank.

D'Anville

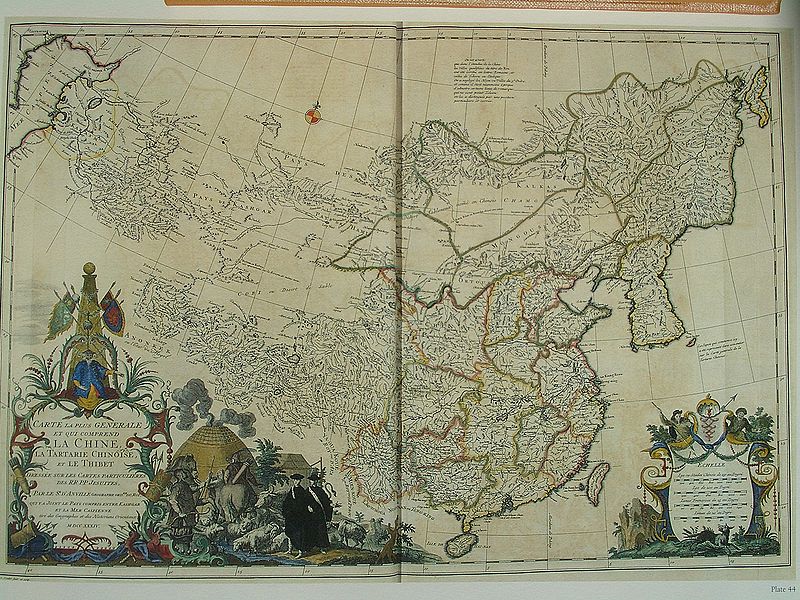

was at first employed in the humbler task of illustrating by maps the

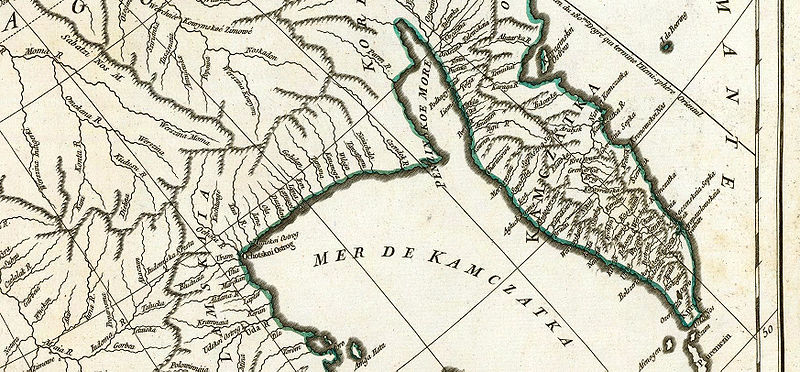

works of different travellers, such as Marchais, Charlevoix, Labat and du Halde. For the history of China by the last-named writer he was employed to make an atlas, which was published separately at the Hague in

1737. In 1735 and 1736 he published two treatises on the figure of the

earth; but these attempts to solve geometrical problems by literary

material were, to a great extent, refuted by Maupertuis' measurements of a degree within the polar circle. D'Anville's historical method was more successful in his 1743 map of Italy,

which first indicated numerous errors in the mapping of that country

and was accompanied by a valuable mémoir (a novelty in such

work), showing in full the sources of the design. A trigonometrical

survey which Benedict XIV soon

after had made in the papal states strikingly confirmed the French

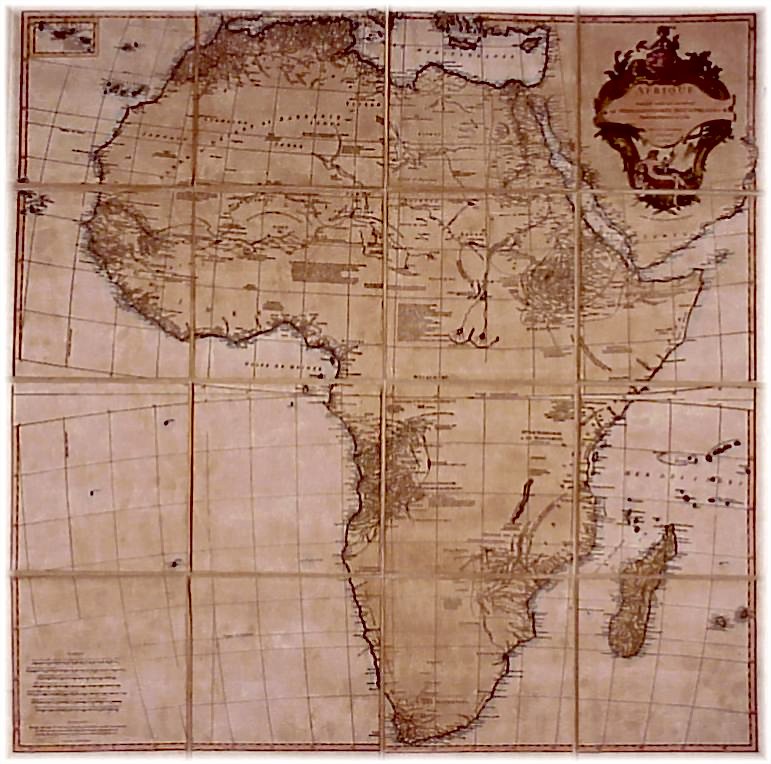

geographer's results. In his later years d'Anville did yeoman service

for ancient and medieval geography, accomplishing something like a

revolution in the former; mapping afresh all the chief countries of the

pre-Christian civilizations (especially Egypt), and by his Mémoire et abrégé de géographie ancienne et générale and his États formés en Europe après la chute de l'empire romain en occident (1771)

rendering his labours still more generally useful. His last employment

consisted in arranging his collection of maps, plans and geographical

materials. It was the most extensive in Europe, and had been purchased

by the king, who, however, allowed him the use of it during his life. This

task performed, he sank into a total imbecility both of mind and body,

which continued for two years, till his death in January 1782. In

1754, at the age of fifty-seven, he became a member of the

Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, whose transactions

he enriched with many papers. In 1775 he received the only place in the

Académie des Sciences which is allotted to geography; and in the

same year he was appointed, without solicitation, first geographer to

the king. The crater Anville on the Moon is named after him, as was the community of Danville, Vermont.