<Back to Index>

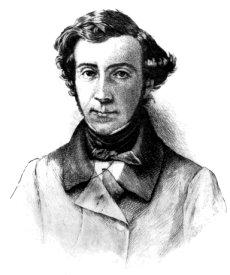

- Historian Alexis Charles Henri Clérel de Tocqueville, 1805

- Composer Mikis Theodorakis, 1925

- 2nd Secretary General of the United Nations Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld, 1905

Alexis-Charles-Henri Clérel de Tocqueville (29 July 1805, Paris – 16 April 1859, Cannes) was a French political thinker and historian best known for his Democracy in America (appearing in two volumes: 1835 and 1840) and The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856). In both of these works, he explored the effects of the rising equality of social conditions on the individual and the state in western societies. Democracy in America (1835), his major work, published after his travels in the United States, is today considered an early work of sociology and political science.

An eminent representative of the classical liberal political tradition, Tocqueville was an active participant in French politics, first under the July Monarchy (1830–1848) and then during the Second Republic (1849–1851) which succeeded the February 1848 Revolution. He retired from political life after Louis Napoléon Bonaparte's 2 December 1851 coup, and thereafter began work on The Old Regime and the Revolution, Volume I. Alexis de Tocqueville came from an old Norman aristocratic family with ancestors who participated in the Battle of Hastings in

1066. His parents, Hervé Louis François Jean Bonaventure

Clérel, Comte de Tocqueville, an officer of the Constitutional Guard of King Louis XVI, and Louise Madeleine Le Peletier de Rosanbo, narrowly avoided the guillotine due to the fall of Robespierre in 1794. After an exile in England, they returned to France during the reign of Napoleon. Under the Bourbon Restoration, his father became a noble peer and prefect. Tocqueville, who despised the July Monarchy (1830–1848), began his political career at the start of the same period, 1830. Thus, he became deputy of the Manche department (Valognes), a position which he maintained until 1851. In parliament, he defended abolitionist views and upheld free trade, while supporting the colonisation of Algeria carried on by Louis-Philippe's regime. Tocqueville was also elected general counsellor of the Manche in 1842, and became the president of the department's conseil général between 1849 and 1851. In

1831, he obtained from the July Monarchy a mission to examine prisons

and penitentiaries in America, and proceeded thither with his life-long

friend Gustave de Beaumont. He returned in less than two years, and published a report, but the real result of his tour was the famous De la Démocratie en Amerique, which appeared in 1835. Apart from America, Tocqueville also made an observational tour of England, producing Memoir on Pauperism. In 1841 and 1846, he traveled to Algeria. His first travel inspired his Travail sur l'Algérie, in which he criticized the French model of colonisation, which was based on an assimilationist view, preferring instead the British model of indirect rule, which avoided mixing different populations together. He went as far as openly advocating racial segregation between the European colonists and the "Arabs" through the implementation of two different legislative systems (a half century before implementation of the 1881 Indigenous code based on religion). After the fall of the July Monarchy during the February 1848 Revolution,

Tocqueville was elected a member of the Constituent Assembly of 1848,

where he became a member of the Commission charged with the drafting of

the new Constitution of the Second Republic (1848–1851). He defended bicameralism (the existence of two parliamentary chambers) and the election of the President of the Republic by universal suffrage.

As the countryside was thought to be more conservative than the

labouring population of Paris, universal suffrage was conceived as a

means to counteract the revolutionary spirit of Paris. During the Second Republic, Tocqueville sided with the parti de l'Ordre against

the socialists. A few days after the February insurrection, he believed

that a violent clash between the Parisian workers' population led by

socialists agitating in favor of a "Democratic and Social Republic" and

the conservatives, which included the aristocracy and the rural

population, was inescapable. As Tocqueville had foreseen, these social

tensions eventually exploded during the June Days Uprising of 1848. Led by General Cavaignac, the repression was supported by Tocqueville, who advocated the "regularization" of the state of siege declared by Cavaignac, and other measures promoting suspension of the constitutional order. Between

May and September, Tocqueville participated to the Constitutional

Commission which Wrote the new Constitution. His propositions

underlined the importance of his American experience as his amendment

about the President and his reelection. A supporter of Cavaignac and of the parti de l'Ordre, Tocqueville, however, accepted an invitation to enter Odilon Barrot's government as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 3 June to 31 October 1849. There, during the troubled days of June 1849, he pleaded with Jules Dufaure,

Interior Minister, for the reestablishment of the state of siege in the

capital and approved the arrest of demonstrators. Tocqueville, who

since February 1848 had supported laws restricting political freedoms,

approved the two laws voted immediately after the June 1849 days, which

restricted the liberty of clubs and freedom of the press. This active support in favor of laws restricting political freedoms stands in contrast of his defense of freedoms in Democracy in America. A closer analysis reveals, however, that Tocqueville favored order as

"the sine qua non for the conduct of serious politics. He [hoped] to

bring the kind of stability to French political life that would permit

the steady growth of liberty unimpeded by the regular rumblings of the

earthquakes of revolutionary change.″ Tocqueville then supported Cavaignac against Louis Napoléon Bonaparte for

the presidential election of 1851. Opposed to Louis Napoléon's 2

December 1851 coup which followed his election, Tocqueville was among

the deputies who gathered at the Xe arrondissement of

Paris in an attempt to resist the coup and have Napoleon III judged for

"high treason," as he had violated the constitutional limit on terms of

office. Detained at Vincennes and then released, Tocqueville, who supported the Restoration of the Bourbons against Bonaparte's Second Empire (1851–1871), quit political life and retreated to his castle (Château de Tocqueville).

Against this image of Tocqueville, biographer Joseph Epstein has

concluded: "Tocqueville could never bring himself to serve a man he

considered a usurper and despot. He fought as best he could for the

political liberty in which he so ardently believed — had given it, in

all, thirteen years of his life [....] He would spend the days

remaining to him fighting the same fight, but conducting it now from

libraries, archives, and his own desk." There, he began the draft of L' Ancien Régime et la Révolution, publishing the first tome in 1856, but leaving the second one unfinished. Tocqueville's professed religion was Roman Catholicism.