<Back to Index>

- Inventor and Businessman Henry Ford, 1863

- Painter, Architect and Art Historian Giorgio Vasari, 1511

- Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando I de' Medici, 1549

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was the American founder of the Ford Motor Company and father of modern assembly lines used in mass production. His introduction of the Model T automobile revolutionized transportation and American industry. He was a prolific inventor and was awarded 161 U.S. patents. As owner of the Ford Motor Company he became one of the richest and best-known people in the world. He is credited with "Fordism", that is, the mass production of large numbers of inexpensive automobiles using the assembly line, coupled with high wages for his workers. Ford had a global vision, with consumerism as the key to peace. Ford did not believe in accountants; he amassed one of the world's largest fortunes without ever having his company audited under his administration. Henry Ford's intense commitment to lowering costs resulted in many technical and business innovations, including a franchise system that put a dealership in every city in North America, and in major cities on six continents. Ford left most of his vast wealth to the Ford Foundation but arranged for his family to control the company permanently.

Henry Ford was born July 30, 1863, on a farm in Greenfield Township (near Detroit, Michigan). His father, William Ford (1826–1905), was born in County Cork, Ireland. His mother, Mary Litogot Ford (1839–1876), was born in Michigan; she was the youngest child of Belgian immigrants; her parents died when Mary was a child and she was adopted by neighbors, the O'Herns. Henry Ford's siblings include Margaret Ford (1867–1938); Jane Ford (c. 1868–1945); William Ford (1871–1917) and Robert Ford (1873–1934). His father gave Henry a pocket watch in his early teens. At fifteen, Ford dismantled and reassembled the timepieces of friends and neighbors dozens of times, gaining the reputation of a watch repairman. At twenty, Ford walked four miles to their Episcopal church every Sunday. Ford was devastated when his mother died in 1876. His father expected him to eventually take over the family farm but Henry despised farm work. He told his father, "I never had any particular love for the farm — it was the mother on the farm I loved."

In 1879, he left home to work as an apprentice machinist in the city of Detroit,

first with James F. Flower & Bros., and later with the Detroit Dry

Dock Co. In 1882, he returned to Dearborn to work on the family farm

and became adept at operating the Westinghouse portable steam engine. He was later hired by Westinghouse company to service their steam engines. Ford married Clara Ala Bryant (c. 1865–1950) in the year 1888 and supported himself by farming and running a sawmill. They had a single child: Edsel Bryant Ford (1893-1943). In 1891, Ford became an engineer with the Edison Illuminating Company,

and after his promotion to Chief Engineer in 1893, he had enough time

and money to devote attention to his personal experiments on gasoline

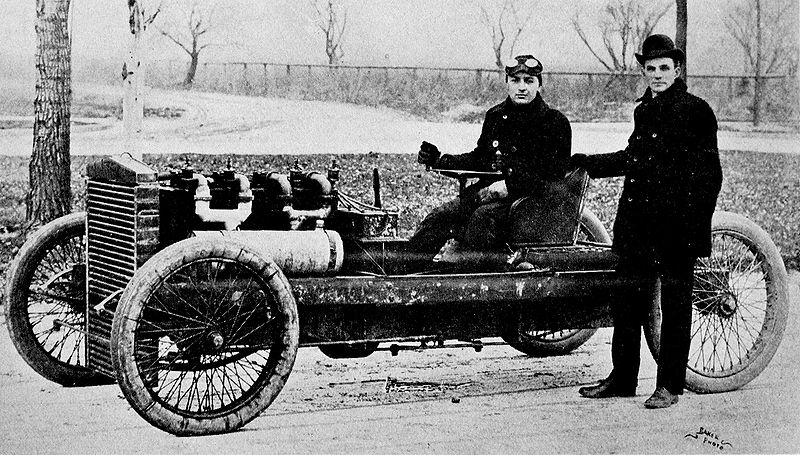

engines. These experiments culminated in 1896 with the completion of

his own self-propelled vehicle named the Ford Quadricycle, which he test-drove on June 4. After various test-drives, Ford brainstormed ways to improve the Quadricycle. Also in 1896, Ford attended a meeting of Edison executives, where he was introduced to Thomas Edison.

Edison approved of Ford's automobile experimentation; encouraged by

Edison's approval, Ford designed and built a second vehicle, which was

completed in 1898. Backed by the capital of Detroit lumber baron William H. Murphy, Ford resigned from Edison and founded the Detroit Automobile Company on August 5, 1899. However,

the automobiles produced were of a lower quality and higher price than

Ford liked. Ultimately, the company was not successful and was

dissolved in January 1901. With the help of C. Harold Wills,

Ford designed, built, and successfully raced a twenty six horsepower

automobile in October 1901. With this success, Murphy and other

stockholders in the Detroit Automobile Company formed the Henry Ford Company on November 30, 1901, with Ford as chief engineer. However, Murphy brought in Henry M. Leland as a consultant. As a result, Ford left the company bearing his name in 1902. With Ford gone, Murphy renamed the company the Cadillac Automobile Company. Ford also produced the 80+ horsepower racer "999", and getting Barney Oldfield to drive it to victory in October 1902. Ford received the backing of an old acquaintance, Alexander Y. Malcomson, a Detroit-area coal dealer. They

formed a partnership, "Ford & Malcomson, Ltd." to manufacture

automobiles. Ford went to work designing an inexpensive automobile, and

the duo leased a factory and contracted with a machine shop owned by John and Horace E. Dodge to supply over $160,000 in parts. Sales were slow, and a crisis arose when the Dodge brothers demanded payment for their first shipment. In

response, Malcomson brought in another group of investors and convinced

the Dodge Brothers to accept a portion of the new company. Ford & Malcomson was reincorporated as the Ford Motor Company on June 16, 1903, with $28,000 capital. The original investors included Ford and Malcomson, the Dodge brothers, Malcomson's uncle John S. Gray, Horace Rackham, and James Couzens. In a newly designed car, Ford gave an exhibition on the ice of Lake St. Clair, driving 1 mile (1.6 km) in 39.4 seconds, setting a new land speed record at 91.3 miles per hour (147.0 km/h). Convinced by this success, the race driver Barney Oldfield,

who named this new Ford model "999" in honor of a racing locomotive of

the day, took the car around the country, making the Ford brand known

throughout the United States. Ford also was one of the early backers of

the Indianapolis 500. Ford

astonished the world in 1914 by offering a $5 per day wage, which more

than doubled the rate of most of his workers. (Using the consumer price index,

this was equivalent to $111.10 per day in 2008 dollars.) The move

proved extremely profitable; instead of constant turnover of employees,

the best mechanics in Detroit flocked to Ford, bringing in their human

capital and expertise, raising productivity, and lowering training

costs. Ford called it "wage motive." The company's use of vertical integration also proved successful when Ford built a gigantic factory that shipped in raw materials and shipped out finished automobiles. The Model T was

introduced on October 1, 1908. It had the steering wheel on the left,

which every other company soon copied. The entire engine and

transmission were enclosed; the four cylinders were cast in a solid

block; the suspension used two semi-elliptic springs. The

car was very simple to drive, and easy and cheap to repair. It was so

cheap at $825 in 1908 (the price fell every year) that by the 1920s a

majority of American drivers learned to drive on the Model T. Ford

created a massive publicity machine in Detroit to ensure every

newspaper carried stories and ads about the new product. Ford's network

of local dealers made the car ubiquitous in virtually every city in

North America. As independent dealers, the franchises grew rich and

publicized not just the Ford but the very concept of automobiling;

local motor clubs sprang up to help new drivers and to explore the

countryside. Ford was always eager to sell to farmers, who looked on

the vehicle as a commercial device to help their business. Sales

skyrocketed — several years posted 100% gains on the previous year.

Always on the hunt for more efficiency and lower costs, in 1913 Ford

introduced the moving assembly belts into his plants, which enabled an

enormous increase in production. Although Henry Ford is often credited

with the idea, contemporary sources indicate that the concept and its

development came from employees Clarence Avery, Peter E. Martin, Charles E. Sorensen, and C. Harold Wills. (Piquette Plant) Sales passed 250,000 in 1914. By 1916, as the price dropped to $360 for the basic touring car, sales reached 472,000. (Using the consumer price index, this price was equivalent to $7,020 in 2008 dollars.) By

1918, half of all cars in America were Model T's. However, it was a

monolithic block; as Ford wrote in his autobiography, "Any customer can

have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black". Until

the development of the assembly line, which mandated black because of

its quicker drying time, Model T's were available in other colors

including red. The design was fervently promoted and defended by Ford,

and production continued as late as 1927; the final total production

was 15,007,034. This record stood for the next 45 years. This record

was achieved in just 19 years flat from the introduction of the first Model T (1908). President Woodrow Wilson asked Ford to run as a Democrat for the United States Senate from Michigan in 1918. Although the nation was at war, Ford ran as a peace candidate and a strong supporter of the proposed League of Nations. Henry Ford turned the presidency of Ford Motor Company over to his son Edsel Ford in

December 1918. Henry, however, retained final decision authority and

sometimes reversed his son. Henry started another company, Henry Ford

and Son, and made a show of taking himself and his best employees to

the new company; the goal was to scare the remaining holdout

stockholders of the Ford Motor Company to sell their stakes to him

before they lost most of their value. (He was determined to have full

control over strategic decisions). The ruse worked, and Henry and Edsel

purchased all remaining stock from the other investors, thus giving the

family sole ownership of the company. By

the mid-1920s, sales of the Model T began to decline due to rising

competition. Other auto makers offered payment plans through which

consumers could buy their cars, which usually included more modern

mechanical features and styling not available with the Model T. Despite

urgings from Edsel, Henry steadfastly refused to incorporate new

features into the Model T or to form a customer credit plan. By

1926, flagging sales of the Model T finally convinced Henry to make a

new model. Henry pursued the project with a great deal of technical

expertise in design of the engine, chassis, and other mechanical

necessities, while leaving the body design to his son. Edsel also

managed to prevail over his father's initial objections in the

inclusion of a sliding-shift transmission. The result was the successful Ford Model A,

introduced in December 1927 and produced through 1931, with a total

output of more than 4 million. Subsequently, the Ford company

adopted an annual model change system similar to that recently

pioneered by its competitor General Motors (and still in use by

automakers today). Not until the 1930s did Ford overcome his objection

to finance companies, and the Ford-owned Universal Credit Corporation became a major car-financing operation. Henry Ford was a pioneer of "welfare capitalism" designed to improve the lot of his workers and especially to reduce the

heavy turnover that had many departments hiring 300 men per year to

fill 100 slots. Efficiency meant hiring and keeping the best workers. Ford

announced his $5-per-day program on January 5, 1914. The revolutionary

program called for a raise in minimum daily pay from $2.34 to $5 for

qualifying workers. It also set a new, reduced workweek, although the

details vary in different accounts. Ford and Crowther in 1922 described

it as six 8-hour days, giving a 48-hour week, while in 1926 they described it as five 8-hour days, giving a 40-hour week. (Apparently

the program started with Saturdays as workdays and sometime later made

them days off.) Ford says that with this voluntary change, labor turnover in his plants went from huge to so small that he stopped bothering to measure it. When Ford started the 40-hour work week and a minimum wage he was criticized by other industrialists and by Wall Street.

He proved, however, that paying people more would enable Ford workers

to afford the cars they were producing and be good for the economy.

Ford explained the change in part of the "Wages" chapter of My Life and Work. He labeled the increased compensation as profit-sharing rather than wages. The

profit-sharing was offered to employees who had worked at the company

for six months or more, and, importantly, conducted their lives in a

manner of which Ford's "Social Department" approved. They frowned on

heavy drinking, gambling, and what might today be called "deadbeat dads".

The Social Department used 50 investigators, plus support staff, to

maintain employee standards; a large percentage of workers were able to

qualify for this "profit-sharing." Ford's

incursion into his employees' private lives was highly controversial,

and he soon backed off from the most intrusive aspects; by the time he

wrote his 1922 memoir, he spoke of the Social Department and of the

private conditions for profit-sharing in the past tense, and admitted

that "paternalism has no place in industry. Welfare work that consists

in prying into employees' private concerns is out of date. Men need

counsel and men need help, oftentimes special help; and all this ought

to be rendered for decency's sake. But the broad workable plan of

investment and participation will do more to solidify industry and

strengthen organization than will any social work on the outside.

Without changing the principle we have changed the method of payment." Ford, an Episcopalian himself, protested against him being called upon by Brazilian authorities and labor unions to build a Catholic parish church for employees near his inland Brazilian factory and its workers settlement Fordlandia. Ford was adamantly against labor unions. He explained his views on unions in Chapter 18 of My Life and Work. He

thought they were too heavily influenced by some leaders who, despite

their ostensible good motives, would end up doing more harm than good

for workers. Most wanted to restrict productivity as a means to foster

employment, but Ford saw this as self-defeating because, in his view,

productivity was necessary for any economic prosperity to exist. He

believed that productivity gains that obviated certain jobs would

nevertheless stimulate the larger economy and thus grow new jobs

elsewhere, whether within the same corporation or in others. Ford also

believed that union leaders (most particularly Leninist-leaning ones)

had a perverse incentive to foment perpetual socio-economic crisis as a

way to maintain their own power. Meanwhile, he believed that smart

managers had an incentive to do right by their workers, because doing

so would actually maximize their own profits. (Ford did acknowledge,

however, that many managers were basically too bad at managing to

understand this fact.) But Ford believed that eventually, if good

managers such as himself could successfully fend off the attacks of

misguided people from both left and right (i.e., both socialists and

bad-manager reactionaries), the good managers would create a

socio-economic system wherein neither bad management nor bad unions

could find enough support to continue existing. To forestall union activity Ford promoted Harry Bennett, a former Navy boxer, to head the Service Department. Bennett employed various intimidation tactics to squash union organizing. The most famous incident, in 1937, was a bloody brawl between company security men and organizers that became known as The Battle of the Overpass. In

the late 1930s and early 1940s, Edsel (who was president of the

company) thought it was necessary for Ford to come to some sort of collective bargaining agreement

with the unions, because the violence, work disruptions, and bitter

stalemates could not go on forever. But Henry (who still had the final

veto in the company on a de facto basis even if not an official one)

refused to cooperate. For several years, he kept Bennett in charge of

talking to the unions that were trying to organize the Ford company.

Sorensen's memoir makes clear that Henry's purpose in putting Bennett in charge was to make sure no agreements were ever reached. The Ford company was the last Detroit automaker to recognize the United Auto Workers union (UAW). A sit-down strike by the UAW union in April 1941 closed the River Rouge Plant. Sorensen said a

distraught Henry Ford was very close to following through with a threat

to break up the company rather than cooperate but that his wife, Clara,

told him she would leave him if he destroyed the family business that

she wanted to see her son and grandsons lead into the future. Henry

complied with his wife's ultimatum, and Ford went literally overnight

from the most stubborn holdout among automakers to the one with the

most favorable UAW contract terms. The contract was signed in June 1941.

Ford, like other automobile companies, entered the aviation business during World War I,

building Liberty engines. After the war, it returned to auto

manufacturing until 1925, when Henry Ford acquired the Stout Metal

Airplane Company. Ford's most successful aircraft was the Ford 4AT Trimotor — called the “Tin Goose” because of its corrugated metal construction. It used a new alloy called Alclad that combined the corrosion resistance of aluminum with the strength of duralumin. The plane was similar to Fokker's

V.VII-3m, and some say that Ford's engineers surreptitiously measured

the Fokker plane and then copied it. The Trimotor first flew on June

11, 1926, and was the first successful U.S. passenger airliner,

accommodating about 12 passengers in a rather uncomfortable fashion.

Several variants were also used by the U.S. Army. Henry Ford has been honored by the Smithsonian Institution for

changing the aviation industry. About 200 Trimotors were built before

it was discontinued in 1933, when the Ford Airplane Division shut down

because of poor sales during the Great Depression. President Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to Detroit as the "Arsenal of Democracy." The Ford Motor Company played a pivotal role in the Allied victory during World War I and World War II. With Europe under siege, the Ford company's genius turned to mass production for the war effort. Specifically, Ford examined the B-24 Liberator bomber, still the most-produced Allied bomber in history, which quickly shifted the balance of power. Before

Ford, and under optimal conditions, the aviation industry could produce

one Consolidated Aircraft B-24 Bomber a day at an aircraft plant. Ford

showed the world how to produce one B-24 an hour at a peak of 600 per

month in 24-hour shifts. Ford's Willow Run factory

broke ground in April 1941. At the time, it was the largest assembly

plant in the world, with over 3,500,000 square feet (330,000 m2). Mass

production of the B-24, led by Charles Sorensen and later Mead Bricker,

began by August 1943. Many pilots slept on cots waiting for takeoff as

the B-24 rolled off the assembly line at Ford's Willow Run facility. Henry Ford opposed war, which he thought was a waste of time. Ford

became highly critical of those who he felt financed war, and he seemed

to do whatever he could to stop them. He felt time was better spent

making things. In 1915, Jewish pacifist Rosika Schwimmer had

gained the favor of Henry Ford, who agreed to fund a peace ship to

Europe, where World War I was raging, for himself and about 170 other

prominent peace leaders. Ford's Episcopalian pastor, Reverend Samuel S.

Marquis, accompanied him on the mission. Marquis also headed Ford's

Sociology Department from 1913 to 1921. Ford talked to President Wilson

about the mission but had no government support. His group went to

neutral Sweden and the Netherlands to meet with peace activists there.

As a target of much ridicule, he left the ship as soon as it reached

Sweden. An article G. K. Chesterton wrote for the December 12, 1916, issue of Illustrated London News, shows

why Ford's effort was ridiculed. Referring to Ford as "the celebrated

American comedian," Chesterton noted that Ford had been quoted

claiming, "I believe that the sinking of the Lusitania was

deliberately planned to get this country [America] into war. It was

planned by the financiers of war." Chesterton expressed "difficulty in

believing that bankers swim under the sea to cut holes in the bottoms

of ships," and asked why, if what Ford said was true, Germany took

responsibility for the sinking and "defended what it did not do." Mr.

Ford's efforts, he concluded, "queer the pitch" of "more plausible and

presentable" pacifists. On the other hand H.G. Wells, in The Shape of Things to Come,

devoted an entire chapter to the Ford Peace Ship, stating that "despite

its failure, this effort to stop the war will be remembered when the

generals and their battles and senseless slaughter are forgotten."

Wells claimed that the American armaments industry and banks, who made

enormous profits from selling munitions to the warring European

nations, deliberately spread lies in order to cause the failure of

Ford's peace efforts. He noted, however, that when the U.S. entered the

war in 1917, Ford took part and made considerable profits from the sale

of munitions. The episode was fictionalized by the British novelist Douglas Galbraith in his novel King Henry. In 1918, with the war still raging and the League of Nations a growing issue in global politics, President Woodrow Wilson encouraged Ford to run for a Michigan seat in the U.S. Senate, believing he would tip the scales in favor of Wilson's proposed League. "You are the only man in Michigan who can be elected and help bring about the peace you so desire," the president wrote

Ford. Ford wrote back: "If they want to elect me let them do so, but I

won't make a penny's investment." Ford did run, however, and came

within 4,500 votes of winning, out of more than 400,000 cast statewide. Ford and Adolf Hitler admired each other's achievements. Adolf Hitler kept a life-size portrait of Ford next to his desk. "I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration," Hitler told a Detroit News reporter two years before becoming the Chancellor of Germany in 1933. In July 1938, four months after the German annexation of Austria, Ford was awarded the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest medal awarded by Nazi Germany to foreigners. Ford disliked the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and

did not approve of U.S. involvement in the war. Therefore, from 1939 to

1943, the War Production Board's dealings with the Ford Motor Company

were with others in the organization, such as Edsel Ford and Charles

Sorensen, much more than with Ford. After Pearl Harbor, Ford initially refused to convert his factories to war work. During

this time, Ford did not stop his executives from cooperating with

Washington, but he himself did not get deeply involved. He watched,

focusing on his own pet side projects, as the work progressed. After Edsel Ford's passing, Henry Ford resumed control of the company in 1943. After years of the Great Depression, labor strife, and New Deal, he suspected people in Washington were conspiring to wrest the company from his control. Ironically,

his paranoia was trending toward self-fulfilling prophesy, as his

attitude inspired background chatter in Washington about how to

undermine his control of the company, whether by wartime government fiat or by instigating some sort of coup among executives and directors. In 1945, "with the company teetering on the brink of bankruptcy," Edsel's widow led an ouster and installed her son, Henry Ford II, as president. In 1918, Ford's closest aide and private secretary, Ernest G. Liebold, purchased an obscure weekly newspaper, The Dearborn Independent for Ford. The Independent ran for eight years, from 1920 until 1927, during which Liebold was editor. The newspaper published "Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion," which was discredited by The Times of London as a forgery during the Independent's publishing run. The American Jewish Historical Society described the ideas presented in the magazine as "anti-immigrant, anti-labor, anti-liquor, and anti-Semitic." In February 1921, the New York World published

an interview with Ford, in which he said "The only statement I care to

make about the Protocols is that they fit in with what is going on."

During this period, Ford emerged as "a respected spokesman for

right-wing extremism and religious prejudice," reaching around 700,000

readers through his newspaper. Along with the Protocols, anti-Jewish articles published by The Dearborn Independent also were released in the early 1920s as a set of four bound volumes, in a non-Ford publication in Weimar Republic Germany cumulatively titled The International Jew, the World's Foremost Problem. Vincent Curcio wrote of these publications that "they were widely distributed and had great influence, particularly in Nazi Germany, where no less a personage than Adolf Hitler read

and admired them." Hitler, fascinated with automobiles, hung Ford's

picture on his wall; Ford is the only American mentioned in Mein Kampf. Steven

Watts wrote that Hitler "revered" Ford, proclaiming that "I shall do my

best to put his theories into practice in Germany, and modeling the Volkswagen, the people's car, on the model T." On February 1, 1924 Ford received a representative of Hitler, Kurt Ludecke, at his home. Ludecke was introduced to Ford by Siegfried Wagner (son of the famous composer Richard Wagner) and Siegfried's wife Winifred Wagner, both Nazi sympathizers and anti-Semites. Ludecke asked Ford for a contribution to the Nazi cause but was apparently refused. Denounced by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the articles nevertheless explicitly condemned pogroms and violence against Jews (Volume 4, Chapter 80), preferring to blame incidents of mass violence on the Jews themselves. None

of this work was actually written by Ford, who wrote almost nothing

according to trial testimony. Friends and business associates have said

they warned Ford about the contents of the Independent and that he probably never read them. (He claimed he only read the headlines.) However,

court testimony in a libel suit, brought by one of the targets of the

newspaper, alleged that Ford did know about the contents of the Independent in advance of publication. A libel lawsuit brought by San Francisco lawyer and Jewish farm cooperative organizer Aaron Sapiro in response to anti-Semitic remarks led Ford to close the Independent in

December 1927. News reports at the time quoted him as being shocked by

the content and having been unaware of its nature. During the trial,

the editor of Ford's "Own Page," William Cameron, testified that Ford

had nothing to do with the editorials even though they were under his

byline. Cameron testified at the libel trial that he never discussed

the content of the pages or sent them to Ford for his approval. Investigative journalist Max Wallace noted that "whatever credibility this absurd claim may have had was soon undermined when James M. Miller, a former Dearborn Independent employee, swore under oath that Ford had told him he intended to expose Sapiro." Michael

Barkun observed, "That Cameron would have continued to publish such

controversial material without Ford's explicit instructions seemed

unthinkable to those who knew both men. Mrs. Stanley Ruddiman, a Ford

family intimate, remarked that 'I don't think Mr. Cameron ever wrote

anything for publication without Mr. Ford's approval.'" Ford's

1927 apology had been well received, "Four-Fifths of the hundreds of

letters addressed to Ford in July of 1927 were from Jews, and almost

without exception they praised the Industrialist." In January 1937, a Ford statement to the Detroit Jewish Chronicle disavowed "any connection whatsoever with the publication in Germany of a book known as the International Jew." In July 1938, prior to the outbreak of war, the German consul at Cleveland gave Ford, on his 75th birthday, the award of the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest medal Nazi Germany could bestow on a foreigner, while James D. Mooney, vice-president of overseas operations for General Motors, received a similar medal, the Merit Cross of the German Eagle, First Class. Distribution of International Jew was halted in 1942 through legal action by Ford despite complications from a lack of copyright, but extremist groups often recycle the material; it still appears on antisemitic and neo-Nazi websites. One

Jewish personality who was said to have been friendly with Ford is

Detroit Judge Harry Keidan. When asked about this connection, Ford

replied that Keidan was only half-Jewish. A close collaborator of Henry

Ford during World War II reported that Ford, at the time being more

than 80 years old, was shown a movie of the Nazi concentration camps.

Ford's

philosophy was one of economic independence for the United States. His

River Rouge Plant became the world's largest industrial complex,

pursuing vertical integration to

such an extent that it could even produce its own steel. Ford's goal

was to produce a vehicle from scratch without reliance on foreign

trade. He believed in the global expansion of his company. He believed

that international trade and cooperation led to international peace,

and he used the assembly line process and production of the Model T to demonstrate it. He

opened Ford assembly plants in Britain and Canada in 1911, and soon

became the biggest automotive producer in those countries. In 1912,

Ford cooperated with Agnelli of Fiat to

launch the first Italian automotive assembly plants. The first plants

in Germany were built in the 1920s with the encouragement of Herbert Hoover and the Commerce Department, which agreed with Ford's theory that international trade was essential to world peace. In

the 1920s Ford also opened plants in Australia, India, and France, and

by 1929, he had successful dealerships on six continents. Ford

experimented with a commercial rubber plantation in the Amazon jungle called Fordlândia; it was one of the few failures. In 1929, Ford accepted Stalin's invitation to build a model plant (NNAZ, today GAZ) at Gorky, a city later renamed Nizhny Novgorod, and he sent American engineers and technicians to help set it up, including future labor leader Walter Reuther. The technical assistance agreement between Ford Motor Company, VSNH and the Soviet-controlled Amtorg Trading Corporation (as purchasing agent) was concluded for nine years and signed on May 31, 1929, by Ford, FMC vice-president Peter E. Martin, V. I. Mezhlauk, and the president of Amtorg,

Saul G. Bron. The Ford Motor Company worked to conduct business in any

nation where the United States had peaceful diplomatic relations. By 1932, Ford was manufacturing one third of all the world’s automobiles. Ford's

image transfixed Europeans, especially the Germans, arousing the "fear

of some, the infatuation of others, and the fascination among all". Germans

who discussed "Fordism" often believed that it represented something

quintessentially American. They saw the size, tempo, standardization,

and philosophy of production demonstrated at the Ford Works as a

national service — an "American thing" that represented the culture of United States.

Both supporters and critics insisted that Fordism epitomized American

capitalist development, and that the auto industry was the key to

understanding economic and social relations in the United States. As

one German explained, "Automobiles have so completely changed the

American's mode of life that today one can hardly imagine being without

a car. It is difficult to remember what life was like before Mr. Ford

began preaching his doctrine of salvation". For many Germans, Henry Ford embodied the essence of successful Americanism. In My Life and Work,

Ford predicted essentially that if greed, racism, and short-sightedness

could be overcome, then eventually economic and technologic development

throughout the world would progress to the point that international

trade would no longer be based on (what today would be called) colonial or neocolonial models and would truly benefit all peoples. His

ideas here were vague, but they were idealistic and they seemed to

indicate a belief in the inherent intelligence of all ethnicities

(which some may find somewhat suspect coming from Ford). Ford

maintained an interest in auto racing from 1901 to 1913 and began his

involvement in the sport as both a builder and a driver, later turning

the wheel over to hired drivers. He entered stripped-down Model Ts in

races, finishing first (although later disqualified) in an

"ocean-to-ocean" (across the United States) race in 1909, and setting a

one-mile (1.6 km) oval speed record at Detroit Fairgrounds in 1911

with driver Frank Kulick. In 1913, Ford attempted to enter a reworked

Model T in the Indianapolis 500 but

was told rules required the addition of another 1,000 pounds

(450 kg) to the car before it could qualify. Ford dropped out of

the race and soon thereafter dropped out of racing permanently, citing

dissatisfaction with the sport's rules, demands on his time by the

booming production of the Model Ts, and his low opinion of racing as a

worthwhile activity. In My Life and Work Ford

speaks (briefly) of racing in a rather dismissive tone, as something

that is not at all a good measure of automobiles in general. He

describes himself as someone who raced only because in the 1890s

through 1910s, one had to race because prevailing ignorance held that

racing was the way to prove the worth of an automobile. Ford did not

agree. But he was determined that as long as this was the definition of

success (flawed though the definition was), then his cars would be the

best that there were at racing. Throughout

the book he continually returns to ideals such as transportation,

production efficiency, affordability, reliability, fuel efficiency,

economic prosperity, and the automation of drudgery in farming and

industry, but rarely mentions, and rather belittles, the idea of merely

going fast from point A to point B. Nevertheless, Ford did make quite an impact on auto racing during his racing years, and he was inducted into the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America in 1996. When

Edsel, president of Ford Motor Company, died of cancer in May 1943, the

elderly and ailing Henry Ford decided to assume the presidency. By this

point in his life, he had had several cardiovascular events (variously

cited as heart attack or stroke) and was mentally inconsistent,

suspicious, and generally no longer fit for such a job. Most

of the directors did not want to see him as president. But for the

previous 20 years, though he had long been without any official

executive title, he had always had de facto control over the company;

the board and the management had never seriously defied him, and this

moment was not different. The directors elected him, and

he served until the end of the war. During this period the company

began to decline, losing more than $10 million a month. The

administration of President Franklin Roosevelt had been considering a government takeover of the company in order to ensure continued war production, but the idea never progressed.

In ill health, he ceded the presidency to his grandson Henry Ford II in September 1945 and went into retirement. He died in 1947 of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 83 in Fair Lane, his Dearborn estate, and he is buried in the Ford Cemetery in Detroit.