<Back to Index>

- Astronaut Charles "Pete" Conrad, Jr., 1930

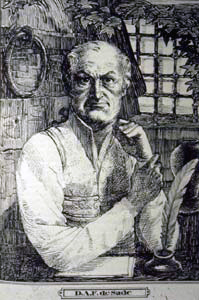

- Author Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade, 1740

- Prime Minister of Romania Ion C. Brătianu, 1821

Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade (2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814) was a French aristocrat and writer famous for his libertine sexuality and lifestyle. His works include novels, short stories, plays, and political tracts; in his lifetime some were published under his own name, while others appeared anonymously and Sade denied being their author. He is best known for his erotic novels, which combined philosophical discourse with pornography, depicting bizarre sexual fantasies with an emphasis on violence, criminality, and blasphemy against the Catholic Church. He was a proponent of extreme freedom (or at least licentiousness), unrestrained by morality, religion or law. Sade was incarcerated in various prisons and in an insane asylum for about 32 years of his life; eleven years in Paris (10 of which were spent in the Bastille) a month in Conciergerie, two years in a fortress, a year in Madelonnettes, three years in Bicêtre, a year in Sainte-Pélagie, and 13 years in the Charenton asylum. Many of his works were written in prison. The term "sadism" is derived from his name.

The Marquis de Sade was born in the Condé palace, Paris, to Comte Jean-Baptiste François Joseph de Sade and Marie-Eléonore de Maillé de Carman, cousin and Lady-in-waiting to the Princess of Condé. He was educated by an uncle, the abbé de Sade. Later, he attended Jesuit lycée, then pursued a military career, becoming Colonel of a Dragoon regiment, and fighting in the Seven Years' War.

In 1763, on returning from war, he courted a rich magistrate's

daughter, but her father rejected his suit, and, instead, arranged a

marriage to his elder daughter, Renée-Pélagie de

Montreuil; that marriage engendered two sons and a daughter. In 1766, he had a private theatre built in his castle at Lacoste in Provence. In January 1767, his father died. The Sade men alternated using the marquis and comte (count) titles. His grandfather, Gaspard François de Sade, was the first to use marquis; occasionally, he was the Marquis de Sade, but is documentarily identified as the Marquis de Mazan. The Sade family were Noblesse d'épée, claiming at the time the oldest, Frank-descended nobility, so, assuming a noble title without a King's grant, was customarily de rigueur. Alternating title usage indicates that titular hierarchy (below duc et pair) was notional; theoretically, the marquis title was granted to noblemen owning several countships,

but its use by men of dubious lineage caused its disrepute. Twentieth-century

descendant, the Comte Xavier de Sade, was the first to defend the

family name and be interested in the Marquis's controversial work.

Until 1948, Comte Xavier had known little of his ancestor because the

Marquis de Sade's works went unpublished and unread in France until the

1960s. Thus, when he found a trunk containing journals, letters,

manuscripts, and legal documents, he granted access to biographer

Gilbert Lêly; the works were published from 1948 to the 1960s.

The Comte Xavier and his descendants own the copyrights and the family

name, a peculiar legal manoeuvre because the Marquis de Sade died and

his copyrights expired two centuries earlier. To avoid association with the Marquis de Sade, descendants have refused the Marquis title.

Bibliographically, the Sade family have some original manuscripts,

others are in universities and libraries, or were destroyed in the

eighteenth century. Moreover, the Comte Xavier de Sade founded a

winery, honouring the Marquis de Sade, vinting champagne and claret,

introduced to market in the late 1980s. Before Comte Xavier, most

descendants were against using any of the Marquis's names, yet he named

a son Donatien. Sade lived a scandalous libertine existence and repeatedly procured young prostitutes as well as employees of both sexes in his castle in Lacoste. He was also accused of blasphemy,

a serious offense at that time. His behavior included an affair with

his wife's sister, Anne-Prospère, who had come to live at the

castle. Beginning

in 1763, Sade lived mainly in or near Paris. Several prostitutes there

complained about mistreatment by him and he was put under surveillance

by the police who made detailed reports of his escapades. After several

short imprisonments, which included a brief incarceration in the Château de Saumur (then a jail), he was exiled to his chateau at Lacoste in 1768. One

of Sade's first major scandals occurred on Easter Sunday in 1768, in

which he procured the sexual services of a woman, Rose Keller –

whether she was a prostitute or not is widely disputed. He was accused

of taking her to his chateau at Arcueil, imprisoning her there and

sexually and physically abusing her. She escaped by climbing out of a

second-floor window and running away. It was at this time that la

Présidente, Sade's mother-in-law, obtained a lettre de cachet from the king, excluding Sade from the jurisdiction of the courts. The lettre de cachet (a

royal order of arrest and imprisonment, without stated cause or access

to the courts) would later prove disastrous for the marquis. An episode in Marseille, in 1772, involved the non-lethal poisoning of prostitutes with the supposed aphrodisiac Spanish fly and sodomy with his manservant Latour. That year the two men were sentenced to death in absentia for

sodomy and said poisoning. They fled to Italy, and Sade took his wife's

sister with him. Sade and Latour were caught and imprisoned at the Fortress of Miolans, in late 1772, but escaped four months later. Sade

later hid at Lacoste where he rejoined his wife who became an

accomplice in his subsequent endeavors. He kept a group of young

employees at Lacoste, most of whom complained about sexual mistreatment

and quickly left his service. Sade was forced to flee to Italy once

again. It was during this time he wrote Voyage d'Italie,

which, along with his earlier travel writings, has never been

translated into English. In 1776 he returned to Lacoste, again hired

several servant girls, most of whom fled. In 1777 the father of one of

those employees came to Lacoste, to claim her, and attempted to shoot

the Marquis at point-blank range. Fortunately for Sade, the gun misfired. Later

that year, Sade was tricked into visiting his supposedly ill mother,

who in fact had recently died, in Paris. He was arrested there and

imprisoned in the Château de Vincennes. He successfully appealed his death sentence in 1778 but remained imprisoned under the lettre de cachet. He escaped but was soon recaptured. He resumed writing and met fellow prisoner Comte de Mirabeau who also wrote erotic works. Despite this common interest, the two came to dislike each other immensely. In 1784 Vincennes was closed and Sade was transferred to the Bastille.

On 2 July 1789 he reportedly shouted out from his cell, to the crowd

outside, "They are killing the prisoners here!" causing something of a

riot. Two days later he was transferred to the insane asylum at Charenton near Paris. (The storming of the Bastille, marking the start of the French Revolution, occurred on 14 July.) He had been working on his magnum opus Les 120 Journées de Sodome (The 120 Days of Sodom).

To his despair he believed that the manuscript was lost during his

transfer; but he continued to write. He was released from Charenton in

1790 after the new Constituent Assembly abolished the instrument of lettre de cachet. His wife obtained a divorce soon after. During

Sade's time of freedom, beginning in 1790, he published several of his

books anonymously. He met Marie-Constance Quesnet, a former actress,

and mother of a six-year-old son, who had been abandoned by her

husband. Constance and Sade would stay together for the rest of his

life. Sade was by this time extremely obese. He initially ingratiated

himself with the new political situation after the revolution,

supported the Republic, called himself "Citizen Sade" and managed to obtain several official positions despite his aristocratic background. Due

to the damage done to his estate in Lacoste which was sacked in 1789 by

an angry mob, he moved to Paris. In 1790 he was elected to the National Convention where he represented the far left.

He was a member of the Piques section, a section notorious for its

radical views. He wrote several political pamphlets, in which he called

for the implementation of direct vote.

However there is much to suggest that he suffered abuse from his fellow

revolutionaries due to his aristocratic background. Matters were not

helped by the desertion of his son, a second lieutenant and the aide-de-camp to an important colonel the Marquis de Toulengeon,

in May 1792. De Sade was forced to disavow his son's desertion in order

to save his neck. Later that year his name was entered - whether by

error or willful malice - on the list of émigrés of the Bouches-du-Rhône department. Appalled by the Reign of Terror in 1793, he wrote an admiring eulogy for Jean-Paul Marat to secure his position. Then he resigned his posts, was accused of "moderatism"

and imprisoned for over a year. This experience presumably confirmed

his life-long detestation of state tyranny and especially of the death penalty. He was released in 1794, after the overthrow and execution of Maximilien Robespierre had effectively ended the Reign of Terror. In

1796, now all but destitute, he had to sell his ruined castle in

Lacoste. The ruins of the castle were acquired in 2001 by fashion

designer Pierre Cardin who now holds music festivals there. In 1801 Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the arrest of the anonymous author of Justine and Juliette. Sade was arrested at his publisher's office and imprisoned without trial; first in the Sainte-Pélagie prison and, following allegations that he had tried to seduce young fellow prisoners there, in the harsh fortress of Bicêtre. After intervention by his family, he was declared insane in 1803 and transferred once more to the asylum at Charenton.

His ex-wife and children had agreed to pay his pension there. Constance

was allowed to live with him at Charenton. The benign director of the

institution, Abbé de Coulmier,

allowed and encouraged him to stage several of his plays, with the

inmates as actors, to be viewed by the Parisian public. Coulmier's

novel approaches to psychotherapy attracted much opposition. In 1809

new police orders put Sade into solitary confinement and deprived him

of pens and paper, though Coulmier succeeded in ameliorating this harsh

treatment. In 1813, the government ordered Coulmier to suspend all

theatrical performances. Sade began an affair with 13-year-old Madeleine Leclerc,

daughter of an employee at Charenton. This affair lasted some 4 years,

until Sade's death in 1814. He had left instructions in his will

forbidding that his body be opened upon any pretext whatsoever, and

that it remain untouched for 48 hours in the chamber in which he died,

and then placed in a coffin and buried on his property located in

Malmaison near Épernon. His skull was later removed from the grave for phrenological examination. His son had all his remaining unpublished manuscripts burned, including the immense multi-volume work Les Journées de Florbelle.