<Back to Index>

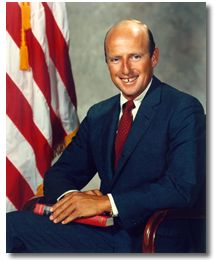

- Astronaut Charles "Pete" Conrad, Jr., 1930

- Author Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade, 1740

- Prime Minister of Romania Ion C. Brătianu, 1821

Charles "Pete" Conrad, Jr. (June 2, 1930 – July 8, 1999), was an American astronaut and engineer, and the third person to walk on the Moon. He also described himself as the first man to dance on the Moon. He flew on Gemini 5 and 11, Apollo 12, and Skylab 2 missions. On the launch of his Gemini 5 flight on August 21, 1965, Conrad became the 10th American and the 20th human to fly in space. Charles “Pete” Conrad, Jr. was born on June 2, 1930, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

the third child and first son of Charles Conrad Sr. and Frances De

Rappelage Conrad (née Vinson), a well-to-do real estate and

banking family. His mother wanted very much to name her newborn son

“Peter,” but Charles insisted that his first son bear his name. In a

compromise between two iron wills, the name on his birth certificate

would read “Charles Conrad, Jr.” but to his mother and virtually all

who knew him, he was “Peter.” When he was 21, his fiancée’s

father called him “Pete” and thereafter, Conrad adopted it. For the

rest of his life, to virtually everyone, he was “Pete.” The Great Depression wiped

out the Conrad family’s fortune, as it did so many others. In 1942,

they lost their Philadelphia manor home and moved into a small carriage

house, paid for by Frances’ brother, Egerton Vinson. Eventually,

Charles Sr., broken by financial failure, moved out. From

the beginning, Conrad was clearly a bright, intelligent child, but he

continually struggled with his schoolwork. He suffered from dyslexia, a condition which was little understood at the time. Conrad attended The Haverford School,

a private academy in Haverford, Pennsylvania, where previous generations

of Conrads had attended. Even after his family’s financial downturn,

his uncle Egerton supported his continued attendance at Haverford.

However, Conrad’s dyslexia continued to frustrate his academic efforts.

After he failed most of his 11th grade exams, Haverford expelled him. Conrad’s mother refused to believe her son was unintelligent, and set about finding him a suitable school. She found the Darrow School in

New Lebanon, New York. There, Conrad learned how to apply a “systems”

approach to learning, and thus, found a way to work around his

dyslexia. Despite having to repeat the 11th grade, Conrad so excelled

at Darrow that after his graduation in 1949, he not only was admitted to Princeton University, but he was also awarded a full Navy ROTC scholarship in the bargain. Starting

when he was fifteen, Conrad worked summers at Paoli Airfield in

Philadelphia, trading lawn mowing, sweeping, and other odd jobs for

airplane rides and occasional stick time. As he grew, and learned more

about the mechanics and workings of aircraft and their engines, he

graduated to minor repairs and maintenance. When he was 16, he drove

almost 100 miles (160 km) to assist a flight instructor whose

plane had been forced to make an emergency landing due to a throttle

malfunction. Conrad repaired the plane single-handedly. Thereafter, the

instructor gave Conrad the formal lessons he needed to earn his pilot’s

license even before he graduated from high school. Conrad

continued flying while in college, not only maintaining his pilot’s

license, but earning an instrument rating as well. He earned his bachelor's degree in Aeronautical Engineering from Princeton University in 1953, after which he entered the United States Navy. Conrad excelled in Navy flight school, and became a carrier pilot, known by the call sign “Squarewave.” Later, he became a flight instructor and a test pilot at Naval Air Station Patuxent River. Conrad was invited to participate in the selection process for what would become the first group of NASA astronauts (the “Mercury Seven”). Conrad, like his fellow candidates, underwent several days of what he

considered invasive, demeaning, and unnecessary medical and

psychological testing at the Lovelace Clinic in New Mexico. Unlike his fellow candidates, however, Conrad rebelled against the regimen. During a Rorschach inkblot test,

he dismissively told the psychiatrist that one blot card revealed a

sexual encounter, complete with lurid detail. When shown the next card,

he studied it for a moment then deadpanned, “It’s upside down.” And

when he was asked to deliver a stool sample to the on-site lab, he

placed it in a gift box and tied a red ribbon around it. Eventually, he

decided he'd had enough. After dropping his full enema bag on the desk

of the Clinic’s commanding officer he walked out. His initial NASA application was denied with the notation "not suitable for long-duration flight." Thereafter, when NASA announced its search for a second group of astronauts, Alan Shepard,

who knew Conrad from their time as Naval aviators and test pilots,

approached Conrad and persuaded him to re-apply. This time, the medical

tests were less offensive and Conrad was invited to join NASA. Conrad

joined NASA as part of the second group of astronauts, known as the New Nine,

on September 17, 1962. Regarded as one of the best pilots in the group,

he was among the first of his group to be assigned a Gemini mission. As

pilot of Gemini 5 (he referred to the capsule as a flying garbage can), along with commander Gordon Cooper,

set a new space endurance record of eight days. The duration of the

Gemini 5 flight was actually 7 days 22 hours and 55 minutes, surpassing

the then-current Russian record of five days. It would take fourteen

days to get to the moon and back and, with the success of Gemini 5, it

was determined that if man could sustain space flight for eight days

then he could surely sustain for fourteen days. Conrad tested many spacecraft systems essential to the Apollo program. Conrad was also one of the smallest of the astronauts in height (1.69 metres (5 feet 6½ inches))

and build so he found the confinement of the Gemini capsule less

onerous than his taller commander. He was then named commander of the Gemini 8 back-up crew, and later commander of Gemini 11 In the aftermath of the January 1967 Apollo 1 disaster, NASA’s plan to incrementally test Saturn V and Apollo spacecraft components leading to the lunar landing had to be significantly revised in order to meet John F. Kennedy’s

goal of reaching the Moon by the end of the decade. Initially, Conrad

was assigned to command the back-up crew for the first flight of the

Saturn V/Apollo spacecraft into high earth orbit, which was initially

scheduled to become Apollo 8. When a “lunar-orbit-without-lunar-module” mission (known in NASA parlance as the “C-prime” mission”) was later approved and inserted into the schedule, that mission became Apollo 8, and the mission backed by Conrad subsequently became Apollo 9. Deke Slayton’s

practice in assigning crews was to assign a back-up crew as prime crew

for the third mission after that crew’s back-up mission. Without the

“C-prime” mission, Conrad might have commanded Apollo 11, which became

the first mission to land on the Moon. On November 14, 1969, Apollo 12 launched with Conrad as commander, Dick Gordon as Command Module Pilot and Alan Bean as

Lunar Module Pilot. The launch was the most harrowing of the Apollo

program, as a series of lightning strikes just after liftoff

temporarily knocked out power and guidance in the command module. Five

days later, after stepping onto the lunar surface, Conrad joked about

his own small stature by remarking: "Whoopee! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that's a long one for me". He later revealed that he said this in order to win a bet he had made with the Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci for $500 to prove that NASA did not script astronaut comments. (In

actuality, Conrad's "long one" and Armstrong's "small step" refer to

two different actions: going from the ladder down to the landing pad,

then stepping horizontally off the pad onto the lunar surface. Conrad's

words for stepping onto the Moon were "Oooh, is that soft and queasy.") Conrad might have returned to the moon had Apollo 20 not been canceled. Conrad's last mission was commander of Skylab 2,

the first crew aboard the space station. This crew had to repair damage

caused by a mishap on launch of the station. On a spacewalk, Conrad

managed to pull free the stuck solar panel by sheer brute force, which

saved the rest of the mission, an action of which he was particularly

proud. Conrad retired from NASA and the Navy in 1973, and went to work for American Television and Communications Company. He worked for McDonnell Douglas from 1976 into the 1990s. After an engine fell off a McDonnell-Douglas DC-10 causing it to crash with the loss of all passengers and crew in

1979, Conrad spearheaded McDonnell-Douglas’s ultimately unsuccessful

efforts to allay the fears of the public and policymakers, and save the

plane’s reputation. During the 1990s he was the ground-based pilot for several test flights of the Delta Clipper experimental single stage to orbit launch vehicle. Conrad had a cameo role in the 1991 TV movie Plymouth. Conrad played himself in the 1975 TV movie Stowaway to the Moon. On February 14, 1996, Conrad was part of the crew on a record-breaking around-the-world flight in a Learjet owned by cable TV pioneer, Bill Daniels. The flight lasted 49 hours, 26 minutes and 8 seconds. Today the jet is on permanent static display at Denver International Airport's Terminal C. In 2006, NASA posthumously awarded him the Ambassador of Exploration Award for his work for the agency and science. While at Princeton, Conrad met Jane DuBose, a student at Bryn Mawr, whose family owned a 1,600-acre (6.5 km2) ranch near Uvalde, Texas.

Her father, Winn DuBose, was the first person to call Conrad “Pete”

rather than “Peter,” the name he had used since birth. Upon his

graduation from Princeton and acceptance of his Navy commission, Conrad

and Jane were married on June 16, 1953. They had four children, all

boys: Peter, born in 1954, Thomas, Andrew, and his youngest,

Christopher, born in 1961. Given

the demands of his career in the Navy and NASA, Pete and Jane spent a

great deal of time apart, and Pete saw less of his boys growing up than

he would have liked. Even after he retired from NASA and the Navy, he

kept himself busy. Soon, Jane had established a separate life for

herself. In 1988, with their sons all grown and moved out, Pete and

Jane divorced. Some years later, Jane remarried. In 1989, Conrad’s youngest son, Christopher, was stricken with a malignant lymphoma. He died in April 1990, at the age of 28. Conrad met Nancy Marjorie Crane, a Denver divorcee, through mutual friends. After a time, their friendship blossomed. Pete Conrad and Nancy Marjorie Crane were married in San Francisco in the spring of 1990. On

July 8, 1999, less than three weeks before the celebrations of the 30th

anniversary of the first moon landing, while motorcycling in Ojai, California, with friends, he ran off the road and crashed. His injuries were first thought to be minor, but he died from internal bleeding about six hours later. He was buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery, with many Apollo-era astronauts in attendance.

,

which docked with an Agena target immediately after achieving orbit: a

maneuver similar to that required for Apollo lunar landing missions.