<Back to Index>

- Egyptologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, 1853

- Sculptor Thomas Ball, 1819

- President of the Confederate States of America Jefferson Finis Davis, 1808

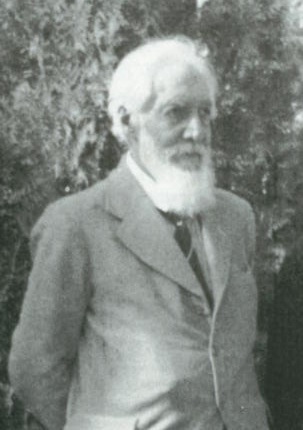

Professor Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie FRS (3 June 1853 – 28 July 1942), known as Flinders Petrie, was an English Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology. He held the first chair of Egyptology in the United Kingdom, and excavated at many of the most important archaeological sites in Egypt, such as Naukratis, Tanis, Abydos and Amarna. Some consider his most famous discovery to be that of the Merneptah Stele, an opinion with which Petrie himself concurred.

Born in Maryon Road, Charlton, Kent (now part of south-east London), England, Petrie was the grandson of Captain Matthew Flinders, surveyor of the Australian coastline. He was raised in a devout Christian household (his father being Plymouth Brethren),

and was educated at home. He had no formal education. His father taught

his son how to survey accurately, laying the foundation for a career

excavating and surveying ancient sites in Egypt and the Levant. Flinders

Petrie was encouraged from childhood in his archaeological interests.

At the age of eight he was being tutored in French, Latin, and Greek,

until he had a collapse and became self-taught. He also ventured his

first archaeological opinion aged eight, when friends visiting the

Petrie family were describing the unearthing of Brading Roman

villa in the Isle of Wight. The boy was horrified to hear the rough

shovelling out of the contents, and protested that the earth should be

pared away, inch by inch, to see all that was in it and how it lay. "All

that I have done since," he wrote when he was in his late seventies,"

was there to begin with, so true it is that we can only develop what is

born in the mind. I was already in archaeology by nature." After

surveying British prehistoric monuments in his teenage years

(commencing with the late Romano-British 'British Camp' that lay within

yards of his family home in Charlton) in attempts to understand their

geometry (at 19 tackling Stonehenge), Petrie travelled to Egypt early in 1880 to apply the same principles in a survey of the Great Pyramid at Giza,

making him the first to properly investigate how they were constructed

(many theories had been advanced on this, and Petrie read them all, but

none were based on first hand observation or logic). Petrie's

published report of this triangulation survey, and his analysis of the

architecture of Giza therein, was exemplary in its methodology and

accuracy, and still provides much of the basic data regarding the

pyramid plateau to this day. On

that visit he was appalled by the rate of destruction of monuments

(some listed in guidebooks had been worn away completely since then)

and mummies. He described Egypt as "a house on fire, so rapid was the

destruction" and felt his duty to be that of a "salvage man, to get all

I could, as quickly as possible and then, when I was 60, I would sit

and write it all down". Having returned to England at the end of 1880, Petrie wrote a number of articles and then met Amelia Edwards, journalist and patron of the Egypt Exploration Fund (now the Egypt Exploration Society), who became his strong supporter and later appointed him as Professor at her Egyptology chair at University College London. Impressed by his scientific approach, they offered him work as the successor to Édouard Naville.

Petrie accepted the position and was given the sum of £250 per

month to cover the excavation’s expenses. In November 1884, Petrie

arrived in Egypt to begin his excavations. He first went to a New Kingdom site at Tanis, with 170 workmen. He cut out the middle man role

of foreman on this and all subsequent excavations, taking complete

overall control himself and removing pressure on the workmen from the

foreman to find finds quickly but sloppily. Though he was regarded as

an amateur and dilettante by

more established Egyptologists, this made him popular with his workers,

who found several small but significant finds that would have been lost

under the old system. By the end of the Tanis dig he ran out of funding but, reluctant to leave

the country in case this was renewed, he spent 1887 cruising the Nile

taking photographs as a less subjective record than sketches. During

this time he also climbed rope ladders at Sehel Island near Aswan to draw and photograph thousands of early Egyptian inscriptions on a cliff face, recording embassies to Nubia, famines and wars. By the time he reached Aswan, a telegram had reached there to confirm the renewal of his funding. He then went straight to the burial site at Fayum,

particularly interested in post-30 BC burials, which had not previously

been fully studied. He found intact tombs and 60 of the famous

portraits, and discovered from inscriptions on the mummies that they

were kept with their living families for generations before burial.

Under Auguste Mariette's arrangements, he sent 50% of these portraits to the Egyptian department of antiquities. However, later finding that Gaston Maspero placed

little value on them and left them open to the elements in a yard

behind the museum to deteriorate, he angrily demanded that they all be

returned, forcing Maspero to pick the 12 best examples for the museum

to keep and then returning 48 to Petrie, which he sent to London for a

special showing at the British Museum. Resuming work, he discovered the village of the Pharaonic tomb-workers. In 1890, Petrie made the first of his many forays into Palestine, leading to much important archaeological work. His six-week excavation of Tell el-Hesi (which was mistakenly identified as Lachish) that year represents the first scientific excavation of an archaeological site in the Holy Land. At another point in the late nineteenth-century, Petrie surveyed a group of tombs in the Wadi al-Rababah (the biblical Hinnom) of Jerusalem,

largely dating to the Iron Age and early Roman periods. Here, in these

ancient monuments, Petrie discovered two different metrical systems. His involvement in Palestinian archaeology was examined in the exhibition "A Future for the Past: Petrie's Palestinian Collection".

The chair of Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology at University College, London was

set up and funded in 1892 by Amelia Edwards. Petrie's supporter since

1880, she made him its first holder. He continued to excavate in Egypt

after taking up the professorship, training many of the best

archaeologists of the day. In 1913 Petrie sold his large collection of

Egyptian antiquities to University College, London, where it is now housed in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. In

early 1896, Petrie and his archaeological team were conducting

excavations on a temple in Petrie's area of concession at Luxor. This

temple complex was located just north of the original funerary temple

of Amenhotep III which had been built on a flood plain. They were initially surprised that this building which they were excavating:

Next, from 1891, he worked on the temple of Aten at Tell-el-Amarna, discovering a 300 square foot New Kingdom painted

pavement of garden and animals and hunting scenes. This became a

tourist attraction but, as there was no direct access to the site,

tourists wrecked neighbouring fields on their way to it. This made

local farmers deface the paintings, and it is only thanks to Petrie's

paintings that their original state is known.

Upon his death in Jerusalem in 1942, influenced by his interest in science, races and different civilisations, Petrie donated his head to the Royal College of Surgeons of London, so that it could be studied for its high intellectual capacity. His body was interred separately in the Protestant Cemetery on Mt. Zion. However, due to the wartime conditions in the area (then still under threat from Rommel's attacks in the North African campaign, which were not repelled until the Second Battle of El Alamein later

that year), his head was delayed in transit from Jerusalem to London.

It was thought to have been lost, but according to the comprehensive

Biography of Petrie by Margaret Drower, it has now been located in

London.