<Back to Index>

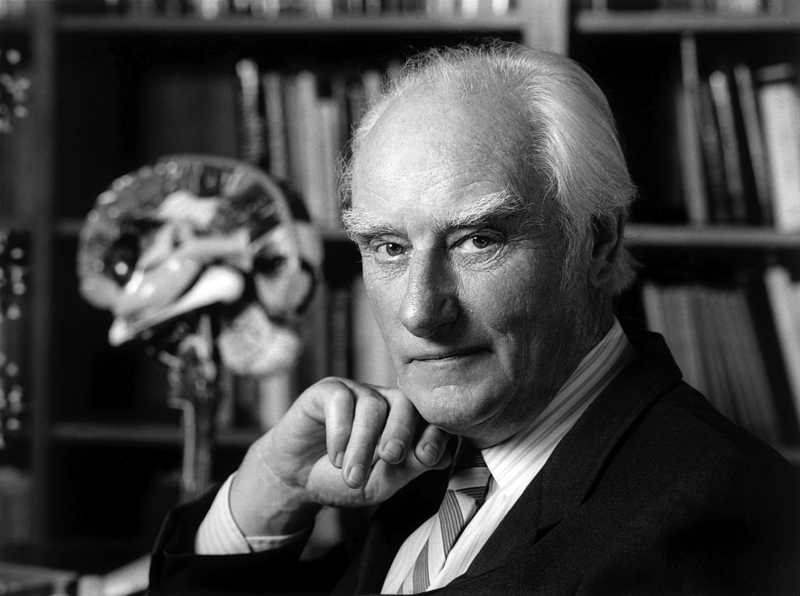

- Biologist Francis Harry Compton Crick, 1916

- Architect Frank Lloyd Wright, 1867

- Second President of Indonesia Suharto, 1921

Francis Harry Compton Crick OM FRS (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004), was a British molecular biologist, physicist, and neuroscientist, and most noted for being one of two co-discoverers of the structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, together with James D. Watson. He, James D. Watson and Maurice Wilkins were jointly awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material".

Crick is widely known for use of the term “central dogma” to summarise an idea that genetic information flow in cells is essentially one-way, from DNA to RNA to protein. Crick was an important theoretical molecular biologist and played a crucial role in research related to revealing the genetic code. During the remainder of his career, he held the post of J.W. Kieckhefer Distinguished Research Professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California. His later research centered on theoretical neurobiology and

attempts to advance the scientific study of human consciousness. He

remained in this post until his death; "he was editing a manuscript on

his death bed, a scientist until the bitter end" said Christof Koch. Francis Crick was the first son of Harry Crick (1887–1948) and Annie Elizabeth Crick, née Wilkins, (1879–1955). He was born and raised in Weston Favell, then a small village near the English town of Northampton in

which Crick’s father and uncle ran the family’s boot and shoe factory.

His grandfather, Walter Drawbridge Crick (1857–1903), an amateur naturalist, wrote a survey of local foraminifera (single-celled protists with shells), corresponded with Charles Darwin, and had two gastropods (snails

or slugs) named after him. At

an early age, Francis was attracted to science and what he could learn

about it from books. As a child, he was taken to church by his parents,

but by about age 12 he told his mother that he no longer wanted to

attend, preferring a scientific search for answers over religious

belief. He was educated at Northampton Grammar School and, after the age of 14, Mill Hill School in London (on scholarship), where he studied mathematics, physics, and chemistry with his best friend John Shilston. At the age of 21, Crick earned a B.Sc. degree in physics from University College of London (UCL) after

he had failed to gain his intended place at a Cambridge college,

probably through failing their requirement for Latin; his

contemporaries in British DNA research Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins both went up to Cambridge colleges, to Newnham and St. John's respectively. Crick later became a PhD student and Honorary Fellow of Caius College and mainly worked at the Cavendish Laboratory and the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. He was also an Honorary Fellow of Churchill College and of University College London. Crick began a Ph.D. research project on measuring viscosity of water at high temperatures (what he later described as "the dullest problem imaginable") in the laboratory of physicist Edward Neville da Costa Andrade, but with the outbreak of World War II (in particular, an incident during the Battle of Britain when a bomb fell through the roof of the laboratory and destroyed his experimental apparatus), Crick was deflected from a possible career in physics. During World War II, he worked for the Admiralty Research Laboratory, from which emerged a group of many notable scientists, including David Bates, Robert Boyd, George Deacon, John Gunn, Harrie Massey and Nevill Mott; he worked on the design of magnetic and acoustic mines and was instrumental in designing a new mine that was effective against German minesweepers. After

World War II, in 1947, Crick began studying biology and became part of

an important migration of physical scientists into biology research.

This migration was made possible by the newly won influence of

physicists such as Sir John Randall, who had helped win the war with inventions such as radar.

Crick had to adjust from the "elegance and deep simplicity" of physics

to the "elaborate chemical mechanisms that natural selection had

evolved over billions of years." He described this transition as,

"almost as if one had to be born again." According to Crick, the

experience of learning physics had taught him something

important — hubris — and the conviction that since physics was already a

success, great advances should also be possible in other sciences such

as biology. Crick felt that this attitude encouraged him to be more

daring than typical biologists who tended to concern themselves with

the daunting problems of biology and not the past successes of physics. For the better part of two years, Crick worked on the physical properties of cytoplasm at Cambridge's Strangeways Laboratory, headed by Honor Bridget Fell, with a Medical Research Council studentship, until he joined Max Perutz and John Kendrew at the Cavendish Laboratory. The Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge was under the general direction of Sir Lawrence Bragg, who won the Nobel Prize in 1915 at the age of 25. Bragg was influential in the effort to beat a leading American chemist, Linus Pauling, to the discovery of DNA's

structure (after having been 'pipped-at-the-post' by Pauling's success

in determining the alpha helix structure of proteins). At the same time

Bragg's Cavendish Laboratory was also effectively competing with King's College London, whose Biophysics department was under the direction of Sir John Randall. (Randall had turned down Francis Crick from working at King's College.) Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins of

King's College were personal friends, which influenced subsequent

scientific events as much as the close friendship between Crick and James Watson. He

married twice, was father to three children and grandfather to six

grandchildren; his brother Anthony (born in 1918) predeceased him in

1966. Crick died of colon cancer on 28 July 2004 at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) Thornton Hospital in La Jolla; he was cremated and his ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean. A public memorial was held on 27 September 2004 at The Salk Institute, La Jolla, near San Diego, California; guest speakers included James D. Watson, Sydney Brenner, Alex Rich, the late Seymour Benzer, Aaron Klug, Christof Koch, Pat Churchland, Vilayanur Ramachandran, Tomaso Poggio, the late Leslie Orgel, Terry Sejnowski, his son Michael Crick, and his youngest daughter Jacqueline Nichols. A more private memorial for his family and colleagues was also held on 3 August 2004.