<Back to Index>

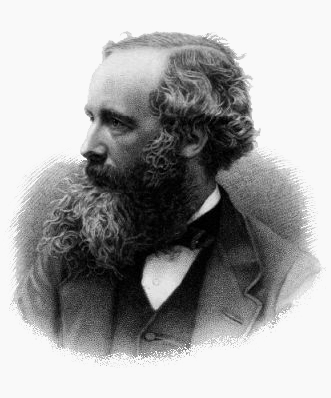

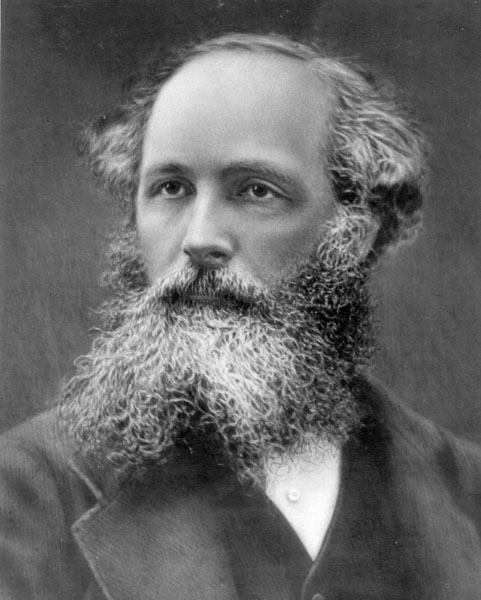

- Physicist James Clerk Maxwell, 1831

- Author William Butler Yeats, 1865

- Holy Roman Emperor Charles the Bald, 823

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish theoretical physicist and mathematician. His most important achievement was classical electromagnetic theory, synthesizing all previously unrelated observations, experiments and equations of electricity, magnetism and even optics into a consistent theory. His set of equations — Maxwell's equations — demonstrated that electricity, magnetism and even light are all manifestations of the same phenomenon: the electromagnetic field. From that moment on, all other classic laws or equations of these disciplines became simplified cases of Maxwell's equations. Maxwell's work in electromagnetism has been called the "second great unification in physics", after the first one carried out by Isaac Newton.

Maxwell demonstrated that electric and magnetic fields travel through space in the form of waves, and at the constant speed of light. Finally, in 1864 Maxwell wrote "A dynamical theory of the electromagnetic field", where he first proposed that light was in fact undulations in the same medium that is the cause of electric and magnetic phenomena. His work in producing a unified model of electromagnetism is considered to be one of the greatest advances in physics. Maxwell also developed the Maxwell distribution, a statistical means of describing aspects of the kinetic theory of gases. These two discoveries helped usher in the era of modern physics, laying the foundation for future work in such fields as special relativity and quantum mechanics. Maxwell is also known for creating the first true colour photograph in 1861 and for his foundational work on the rigidity of rod-and-joint frameworks like those in many bridges.

Maxwell

is considered by many physicists to be the 19th-century scientist with

the greatest influence on 20th-century physics. His contributions to

the science are considered by many to be of the same magnitude as those

of Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein. In

the end of millennium poll, a survey of the 100 most prominent

physicists saw Maxwell voted the third greatest physicist of all time,

behind only Newton and Einstein. On

the centennial of Maxwell's birthday, Einstein himself described

Maxwell's work as the "most profound and the most fruitful that physics

has experienced since the time of Newton." Einstein kept a photograph of Maxwell on his study wall, alongside pictures of Michael Faraday and Newton. James Clerk Maxwell was born on 13 June 1831 at 14 India Street, Edinburgh, to John Clerk Maxwell, an advocate, and Frances Maxwell (née Cay). Maxwell's father was a man of comfortable means, related to the Clerk family of Penicuik, Midlothian, holders of the baronetcy of Clerk of Penicuik; his brother being the 6th Baronet. He had been born John Clerk, adding the surname Maxwell to his own after he inherited a country estate in Middlebie, Kirkcudbrightshire from connections to the Maxwell family, themselves members of the peerage. Maxwell's parents did not meet and marry until they were well into their thirties, unusual

for the times, and Frances Maxwell was nearly 40 when James was born.

They had had one earlier child, a daughter, Elizabeth, who died in

infancy. They

named their only surviving child James, a name that had sufficed not

only for his grandfather, but also many of his other ancestors. The family moved when Maxwell was young to "Glenlair", a house his parents had built on the 1500 acre (6.1 km2) Middlebie estate. All indications suggest that Maxwell had maintained an unquenchable curiosity from an early age. By the age of three, everything that moved, shone, or made a noise drew the question: "what's the go o' that?". Recognizing the potential of the young boy, his mother Frances took responsibility for James' early education, which in Victorian era was largely the job of the woman of the house. She

was however taken ill with abdominal cancer, and after an unsuccessful

operation, died in December 1839 when Maxwell was only eight. James'

education was then overseen by John Maxwell and his sister-in-law Jane,

both of whom played pivotal roles in the life of Maxwell. His

formal schooling began unsuccessfully under the guidance of a

sixteen-year old hired tutor. Little is known about the young man John

Maxwell hired to instruct his son, except that he treated the younger boy harshly, chiding him for being slow and wayward. John Maxwell dismissed the tutor in November 1841, and after considerable thought, sent James to the prestigious Edinburgh Academy. He

lodged during term times at the house of his aunt Isabella; while there

his passion for drawing was encouraged by his older cousin Jemima, herself a talented artist. The ten-year old Maxwell, raised in isolation on his father's countryside estate, did not fit in well at school. The first year had been full, obliging him to join the second year with classmates a year his senior. His mannerisms and Galloway accent

struck the other boys as rustic, and arriving on his first day at

school wearing home-made shoes and tunic earned him the unkind nickname

of "Daftie". Maxwell, however, never seemed to have resented the epithet, bearing it without complaint for many years. Any social isolation at the Academy however ended when he met Lewis Campbell and Peter Guthrie Tait, two boys of a similar age, and themselves to become notable scholars. They would remain lifetime friends. Maxwell was fascinated by geometry at an early age, rediscovering the regular polyhedron before any formal instruction. Much

of his talent went unnoticed however, and, despite winning the school's

scripture biography prize in his second year, his academic work

remained unremarkable, until, at the age of 13, he won the school's mathematical medal, and first prizes for English and poetry. For his first scientific work, at the age of only 14, Maxwell wrote a paper describing a mechanical means of drawing mathematical curves with a piece of twine, and the properties of ellipses and curves with more than two foci. His work, "Oval Curves", was presented to the Royal Society of Edinburgh by James Forbes, professor of natural philosophy at Edinburgh University, Maxwell deemed too young for the task. The work was not entirely original, Descartes having

examined the properties of such multifocal curves in the seventeenth

century, though Maxwell had simplified their construction. Maxwell left the Academy in 1847 at the age of 16 and began attending classes at the University of Edinburgh. Having

the opportunity to attend Cambridge after his first term, Maxwell

decided instead to complete the full course of his undergraduate

studies at Edinburgh. The academic staff of Edinburgh University

included some highly regarded names, and Maxwell's first year tutors

included Sir William Hamilton, who lectured him on logic and metaphysics, Philip Kelland on mathematics, and James Forbes on natural philosophy. Maxwell did not however find his classes at Edinburgh very demanding, and

was able to immerse himself in private study during free time at the

university, and particularly when back home at Glenlair. There

he would experiment with improvised chemical and electromagnetic

apparatus, but his chief preoccupation was the properties of polarized light. He constructed shaped blocks of gelatine, subjecting them to various stresses, and with a pair of polarizing prisms gifted him by the famous scientist William Nicol, would view the coloured fringes developed within the jelly. Maxwell had discovered photoelasticity, a means of determining the stress distribution within physical structures. In his eighteenth year, Maxwell contributed two papers for the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh — one

of which, "On the equilibrium of elastic solids", laid the foundation

for an important discovery of his later life: the temporary double refraction produced in viscous liquids by shear stress. The

other was titled "Rolling curves". As with his schoolboy paper "Oval

Curves", Maxwell was considered too young to stand at the rostrum and

present it himself, and it was delivered to the Royal Society by his

tutor Kelland. In October 1850, already an accomplished mathematician, Maxwell left Scotland for Cambridge University. He initially attended Peterhouse, but before the end of his first term transferred to Trinity College, where he believed it would be easier to obtain a fellowship. At Trinity, he was elected to the elite secret society known as the Cambridge Apostles. In November 1851, Maxwell studied under William Hopkins, whose success in nurturing mathematical genius had earned him the nickname of "senior wrangler-maker". A considerable part of Maxwell's translation of his electromagnetism equations was accomplished during his time in Trinity. In

1854, Maxwell graduated from Trinity with a degree in mathematics. He

scored second highest in the final examination, coming behind Edward Routh, and thereby earning himself the title of Second Wrangler, but was declared equal with Routh in the more exacting ordeal of the Smith's Prize examination. Immediately

after taking his degree, Maxwell read to the Cambridge Philosophical

Society a novel memoir, "On the transformation of surfaces by bending". This

is one of the few purely mathematical papers he published, and it

demonstrated Maxwell's growing stature as a mathematician. Maxwell decided to remain at Trinity after graduating and applied for a fellowship, a process that he could expect to take a couple of years. Buoyed

by his success as a research student, he would be free, aside from some

tutoring and examining duties, to pursue scientific interests at his

own leisure. The nature and perception of colour was one such interest, and had begun at Edinburgh University while he was a student of Forbes. Maxwell took the coloured spinning tops invented by Forbes, and was able to demonstrate that white light would result from a mixture of red, green and blue light. His

paper, "Experiments on colour", laid out the principles of colour

combination, and was presented to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in

March 1855. This time, it would be Maxwell himself who delivered his lecture. Maxwell was made a fellow of Trinity on 10 October 1855, sooner than was the norm, and was asked to prepare lectures on hydrostatics and optics, and to set examination papers. However, the following February he was informed by Forbes that the Chair of Natural Philosophy at Marischal College, Aberdeen, had become vacant, and urged to apply. His

father assisted him in the task of preparing the necessary references,

but died on 2 April at Glenlair before either knew the result of

Maxwell's candidacy. Maxwell nevertheless accepted the professorship at Aberdeen, leaving Cambridge in November 1856. The

twenty-five year old Maxwell was a decade and a half younger than any

other professor at Marischal, but engaged himself with his new

responsibilities as head of department, devising the syllabus and

preparing the lectures. He committed himself to lecturing 15 hours a week, including a weekly pro bono lecture to the local working men's college. He

lived in Aberdeen during the six months of the academic year, and would

spend the summers at Glenlair, which he had inherited from his father. His mind was focused on a conundrum which had eluded scientists for two hundred years: the nature of Saturn's rings.

It was unknown how they could remain stable without breaking up,

drifting away or crashing into Saturn. The problem took on a particular

resonance at this time as St John's College, Cambridge had chosen it as the topic for the 1857 Adams Prize. Maxwell

devoted two years to studying the problem, proving that a regular solid

ring could not be stable, and a fluid ring would be forced by wave

action to break up into blobs. Neither met with observations, and

Maxwell was able to conclude that the rings must comprise numerous

small particles he called "brick-bats", each independently orbiting

Saturn. Maxwell

was awarded the £130 Adams Prize in 1859 for his essay "On the

stability of saturn's rings"; he was the only entrant to have made

enough headway to submit an entry. His work was so detailed and convincing that when George Biddell Airy read it he commented "It is one of the most remarkable applications of mathematics to physics that I have ever seen." It was considered the final word on the issue until direct observations by the Voyager flybys of the 1980s, which confirmed Maxwell's prediction. Maxwell

had in 1857 befriended the Principal of Marischal, the Reverend Daniel

Dewar, and through him he was to meet Dewar's daughter, Katherine Mary

Dewar. They were engaged in February 1858, marrying in Aberdeen on 2

June 1859. Comparatively little is known of Katherine, seven years

Maxwell's senior: Maxwell's biographer and friend Campbell adopted an

uncharacteristic reticence on the subject, though describing their

married life as "one of unexampled devotion". In 1860, Marischal College merged with the neighbouring King's College to form the University of Aberdeen.

There was no room for two professors of Natural Philosophy, and Maxwell

found himself in the extraordinary position for someone of his

scientific stature of being laid off. He was unsuccessful applying for

Forbes' recently vacated chair at Edinburgh, the post going to Tait,

but was granted instead the Chair of Natural Philosophy at King's College London. After recovering from a near-fatal bout of smallpox in the summer of 1860, Maxwell headed south to London with his wife Katherine. Maxwell's time at King's was probably the most productive of his career. He was awarded the Royal Society's Rumford Medal in 1860 for his work on colour, and elected to the Society itself in 1861. This period of his life would see him display the world's first colour photograph, develop further his ideas on the viscosity of gases, and proposed a system of defining physical quantities, now known as dimensional analysis. Maxwell would often attend lectures at the Royal Institution, where he came into regular contact with Michael Faraday.

The relationship between the two men could not be described as

close — Faraday was 40 years Maxwell's senior and showing signs of senility — but they maintained a strong respect for each other's talents. The

time is especially known for the advances Maxwell made in

electromagnetism. He had examined the nature of electromagnetic fields

in his two-part 1861 paper "On physical lines of force", in which he

had provided a conceptual model for electromagnetic induction, consisting of tiny spinning cells of magnetic flux. A further two parts to the paper were published early in 1862, in the first of which he discussed the nature of electrostatics and displacement current. The final part dealt with the rotation of the plane of polarization of light in a magnetic field, a phenomenon discovered by Faraday and now known as the Faraday effect. In 1865, Maxwell resigned the chair at King's College London and returned to Glenlair with Katherine. He wrote a textbook of the Theory of Heat (1871), and an elementary treatise on Matter and Motion (1876). Maxwell was also the first to make explicit use of dimensional analysis in 1871. In 1871, he became the first Cavendish Professor of Physics at Cambridge. Maxwell was put in charge of the development of the Cavendish Laboratory.

He supervised every step of the progress of the building and of the

purchase of the very valuable collection of apparatus paid for by its

generous founder, the 7th Duke of Devonshire (chancellor

of the university, and one of its most distinguished alumni). One of

Maxwell's last great contributions to science was the editing (with

copious original notes) of the electrical researches of Henry Cavendish, from which it appeared that Cavendish researched such questions as the mean density of the earth and the composition of water, among other things. He died in Cambridge of abdominal cancer on 5 November 1879 at the age of 48. Maxwell is buried at Parton Kirk, near Castle Douglas in Galloway, Scotland. The extended biography The Life of James Clerk Maxwell, by his former school fellow and lifelong friend Professor Lewis Campbell,

was published in 1882 and his collected works, including the series of

articles on the properties of matter, such as "Atom", "Attraction",

"Capillary action", "Diffusion", "Ether", etc., were issued in two

volumes by the Cambridge University Press in 1890. A collection of his poems was published by his friend Lewis Campbell in 1882.

Ivan Tolstoy, author of one of Maxwell's biographies, remarked at the frequency with which scientists writing short biographies on Maxwell often omit the subject of his Christianity. Maxwell's religious beliefs and related activities have been the focus of several peer-reviewed and well-referenced papers. Attending both Presbyterian and Episcopalian services as a child, Maxwell later underwent an evangelical conversion (April 1853), which committed him to an anti-positivist position. As a great lover of British poetry, Maxwell memorised poems and wrote his own. The best known is Rigid Body Sings, closely based on Comin' Through the Rye by Robert Burns, which he apparently used to sing while accompanying himself on a guitar. It has the immortal opening lines

Flyin' through the air.

Gin a body hit a body,

Will it fly? And where?