<Back to Index>

- Psychologist Erik Erikson, 1902

- Painter Nicolas Poussin, 1594

- Prime Minister of Romania Ion Victor Antonescu, 1882

Ion Victor Antonescu (June 15, 1882 – June 1, 1946) was a Romanian soldier, authoritarian politician and convicted war criminal. The Prime Minister and Conducător during most of World War II, he presided over two successive wartime dictatorships. A Romanian Army career officer who made his name during the1907 peasants' revolt and the World War I Romanian Campaign, the antisemitic Antonescu sympathized with the far right and fascist National Christian and Iron Guard groups for much of the interwar period. He was a military attaché to France and later Chief of the General Staff, briefly serving as Defense Minister in the National Christian cabinet of Octavian Goga. During the late 1930s, his political stance brought him into conflict with King Carol II and led to his detainment. Antonescu nevertheless rose to political prominence during the political crisis of 1940, and established the National Legionary State, an uneasy partnership with the Iron Guard's leader Horia Sima. After entering Romania into an alliance with Nazi Germany and the Axis and ensuring Adolf Hitler's confidence, he eliminated the Guard during the Legionary Rebellion of 1941. In addition to leadership of the executive, he assumed the offices of Foreign Affairs and Defense Minister. Soon after Romania joined the Axis in Operation Barbarossa, recovering Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, Antonescu also became Marshal of Romania.

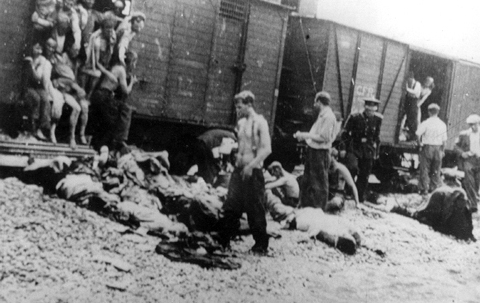

An atypical figure among Holocaust perpetrators, Antonescu enforced policies independently responsible for the deaths of as many as 400,000 people, most of them Bessarabian, Ukrainian and Romanian Jews, as well as Romani Romanians. The regime's complicity in the Holocaust combined pogroms and mass murders such as the Odessa massacre with ethnic cleansing, systematic deportations to occupied Transnistria and widespread criminal negligence. The system in place was nevertheless characterized by singular inconsistencies, prioritizing plunder over killing, showing leniency toward most Jews in the Old Kingdom, and ultimately refusing to adopt the Final Solution as applied throughout Nazi-occupied Europe.

Confronted with heavy losses on the Eastern Front, Antonescu embarked on inconclusive negotiations with the Allies, just before a political coalition, formed around the young monarch Michael I, toppled him during the August 23, 1944 Coup. After a brief detention in the Soviet Union, the deposed Conducător was handed back to Romania, where he was tried by a special People's Tribunal and executed. This was part of a series of trials that also passed sentences on his various associates, as well as his wife Maria. The judicial procedures earned much criticism for responding to the Romanian Communist Party's ideological priorities, a matter that fueled nationalist and

far right attempts to have Antonescu posthumously exonerated. While

these groups elevated Antonescu to the status of hero, his involvement

in the Holocaust was officially reasserted and condemned following the

2003 Wiesel Commission report. Born in Piteşti town, north-west of the capital Bucharest, Antonescu was the scion of an upper-middle class Romanian Orthodox family with some military tradition. He was especially close to his mother, Liţa Baranga, who survived his death. His

father, an army officer, wanted Ion to follow in his footsteps, and as

such, he sent him to attend the Infantry and Cavalry School in Craiova. According to one account, Ion Antonescu was briefly a classmate of Wilhelm Filderman, the future Romanian Jewish community activist whose interventions with Conducător Antonescu helped save a number of his coreligionists. After

graduation, in 1904, Antonescu joined the Romanian Army with the rank

of Second Lieutenant. He spent the following two years attending

courses at the Special Cavalry Section in Târgovişte. Reportedly,

he was a zealous and goal-setting student, upset by the slow pace of

promotions, and compensating for his diminutive stature through

toughness. In time, the reputation of being a tough and ruthless commander, together with his reddish hair earned him the nickname Câinele Roşu ("The Red Dog"). Antonescu

also developed a reputation for questioning his commanders, and for

appealing over their heads whenever he felt they were wrong. During the repression of the 1907 peasants' revolt, he was the head of a cavalry unit in Covurlui County. Opinions

on his role in the events diverge: while some historians believe

Antonescu was a particularly violent participant in quelling the revolt, others equate his participation with that of regular officers or view it as outstandingly tactful. In addition to restricting peasant protests, Antonescu's unit subdued socialist activities in Galaţi port. His handling of the situation earned him praise from King Carol I, who sent Crown Prince (future monarch) Ferdinand to congratulate him in front of the whole garrison. The following year, Antonescu was promoted to Lieutenant, and, between 1911 and 1913, he attended the Advanced War School, receiving the rank of Captain upon graduation. In 1913, during the Second Balkan War against Bulgaria, Antonescu served as a staff officer in the First Cavalry Division in Dobruja. After 1916, when the Kingdom of Romania entered World War I on the Entente side, Ion Antonescu acted as chief of staff for General Constantin Prezan. In August 1916, upon the start of the Romanian campaign, Romanian troops crossed the Carpathian Mountains, marching into the Austro-Hungarian-ruled region of Transylvania, but their effort was halted when the Central Powers opened new fronts. Bulgarian and Imperial German armies decisively defeated their ill-equipped and poorly-defended Romanian adversaries in the Battle of Turtucaia (August 24), and advanced into Dobruja. When enemy troops crossed the mountains from Transylvania into Wallachia, Antonescu was ordered to design a defense plan for Bucharest. The Romanian royal court, army and administration were subsequently forced to retreat into Moldavia,

the last portion of territory still under Romanian control. Henceforth,

Antonescu took part in any important decision involving defensive

efforts, an unusual promotion which probably stoked his ambitions. In December, as Prezan became the Chief of the General Staff,

Antonescu, who was by now a major, was named the head of operations,

being involved in the defense of Moldavia. He contributed to the

tactics used during the Battle of Mărăşeşti (July-August 1917), when Romanians under General Alexandru Averescu managed to stop the advance of German forces under the command of Field Marshal August von Mackensen. Antonescu lived in Prezan's proximity for the remainder of the war, and influenced his decisions. That autumn, the October Revolution in Russia removed Romania's main ally, the Russian Provisional Government, from the conflict. Its successor, Bolshevik Russia, made peace with the Central Powers under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, leaving Romania the only enemy of the Central Powers on the Eastern Front. In these conditions, the Romanian government signed, and the Parliament ratified, Romania's own peace treaty with the Central Powers.

Romania broke the treaty later in the year, on the grounds that King

Ferdinand I had not signed it. During the interval, Antonescu, who

viewed the separate peace as "the most rational solution", was assigned command over a cavalry regiment. The renewed offensive played a part in ensuring the union of Transylvania with Romania. After the war, Antonescu's merits as an operations officer were noticed by, among others, politician Ion G. Duca, who wrote that "his intelligence, skill and activity, brought credit on himself and invaluable service to the country". Another

event occurring late in the war is also credited with having played a

major part in Antonescu's life: in 1918, Crown Prince Carol (the future King Carol II) eloped and technically deserted his army posting, to marry the commoner Zizi Lambrino. This outraged Antonescu, who developed enduring contempt for the future king. Lieutenant Colonel Ion Antonescu retained his visibility in the public eye during the interwar period. He participated in the political campaign to earn recognition at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 for Romania's gains in Transylvania. His nationalist argument about a future state of the Romanians was published as the essay Românii. Origina, trecutul, sacrificiile şi drepturile lor ("The

Romanians. Their Origin, Their Past, Their Sacrifices and Their

Rights"). The booklet advocated extension of Romanian rule beyond the

confines of Greater Romania, and recommended, at the risk of war with the emerging Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the annexation of all Banat areas and the Timok Valley. In March 1920, Antonescu was one of three people nominated by the new Averescu executive to be a military attaché of Romania in France, but a report issued by the French military observer in Romania, General Victor Pétin,

was negative enough to make the French side choose a certain Colonel

Şuţu instead (the text referred to Antonescu as "extremely vain", "chauvinistic" and "xenophobic", while acknowledging his "great military worth"). Nevertheless, Şuţu had to leave Paris in

1922, and when the Romanian government nominated Antonescu again, the

French government felt obliged to accept his nomination, despite

renewed criticism from Pétin's part. At the moment of his reassignment, Antonescu was handling military instruction in the Transylvanian city of Sibiu, where his rebellious attitude was causing irritation among his commanders. From 1923, Antonescu was also the Romanian attaché in the United Kingdom and Belgium. After embarking on his mission, he negotiated a credit worth 100 million French francs for Romania to purchase French weaponry, and worked together with Romanian League of Nations diplomat Nicolae Titulescu; the two became personal friends. According to one account, he was also in contact with the Romanian-born conservative aristocrat and writer Marthe Bibesco, who is reported to have introduced Antonescu to the ideas of Gustave Le Bon, a researcher of crowd psychology who had an influence on fascist leaders. The same story has it that Bibesco saw the Romanian officer as a new version of 19th century nationalist rebel Georges Boulanger, introducing him as such to Le Bon. In 1923, he made the acquaintance of lawyer Mihai Antonescu, who was to become his close friend, legal representative and political associate. After

returning to Romania in 1926, Antonescu returned to his teaching

position in Sibiu, and, in autumn 1928, was Secretary-General of the Defense Ministry in the Vintilă Brătianu cabinet. He married Maria Niculescu, for long a resident of France, who had been married twice before: to a Romanian Police officer, with whom she had a son, Gheorghe (died 1944), and to a Frenchman of Jewish origin. After a period as Deputy Chief of the General Staff, he was appointed its Chief (1933–1934). These assignments coincided with the rule of Carol's underage son Michael I and his regents, and with Carol's seizure of power in 1930. During this period Antonescu first grew interested in the Iron Guard, an antisemitic and fascist-related movement headed by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu.

In his capacity as Deputy Chief of Staff, he ordered the Army's

intelligence unit to compile a report on the faction, and made a series

of critical notes on Codreanu's various statements. As

Chief of Staff, Antonescu reportedly had his first confrontation with

the political class and the monarch. His projects for weapon

modernization were questioned by Defense Minister Paul Angelescu, leading Antonescu to present his resignation. According to another account, he completed an official report on the embezzlement of Army funds, which indirectly implicated Carol and his camarilla (see Škoda Affair). The king consequently ordered him out of office, provoking indignation among sections of the political mainstream. On Carol's orders, Antonescu was placed under surveillance by the Siguranţa Statului intelligence service, and closely monitored by the Interior Ministry Undersecretary Armand Călinescu. The

officer's political credentials were on the rise, and he had contacts

with all sides of the political spectrum, while support for Carol

plummeted. Antonescu maintained contacts with the two main democratic

groups, the National Liberal and the National Peasants' parties (known respectively as PNL and PNŢ). He was also engaged in discussions with the rising far right, antisemitic and fascist movements: although in competition with each other, both the National Christian Party (PNC) of Octavian Goga and the Iron Guard sought to attract Antonescu to their side. In 1936, to the authorities' alarm, Army General and Iron Guard member Gheorghe Cantacuzino-Grănicerul arranged

a meeting between Ion Antonescu and the movement's leader: Antonescu is

reported to have found Codreanu arrogant, but to have welcomed his

revolutionizing approach to politics. In late 1937, after the December general election came to an inconclusive result, Carol appointed Goga Prime Minister over a far right cabinet that was the first executive to impose racial discrimination in its treatment of the Jewish community. Goga's appointment was meant to curb the rise of the more popular and even more radical Codreanu. Initially given the Communications portfolio by

his former rival, Interior Minister Armand Călinescu, Antonescu

repeatedly demanded the office of Defense Minister, which he was

eventually granted. His

mandate coincided with a troubled period, and saw Romania having to

chose between its traditional alliance with France, Britain, the

crumbling Little Entente and the League of Nations or moving closer to Nazi Germany and its Anti-Comintern Pact.

Antonescu's own contribution is disputed by historians, who variously

see him as either a supporter of the Anglo-French alliance or, like the

PNC itself, more favorable to cooperation with Adolf Hitler's Germany. At the time, Antonescu viewed Romania's alliance with the Entente as insurance against Hungarian and Soviet revanchism, but, as an anti-communist, he was suspicious of the Franco-Soviet rapprochement. Particularly concerned about Hungarian demands in Transylvania, he ordered the General Staff to prepare for a western attack. However,

his major contribution in office was in relation to an internal crisis:

as a response to violent clashes between the Iron Guard and the PNC's

own fascist militia, the Lăncieri, Antonescu extended the already imposed martial law. The Goga cabinet ended when the tentative rapprochement between Goga and Codreanu prompted

Carol to overthrow the democratic system and proclaim his own

authoritarian regime. The deposed Premier died in 1938, and Antonescu

remained close friend of his widow, Veturia Goga. By

that time, revising his earlier stance, Antonescu had also built a

close relationship with Codreanu, and was even said to have become his

confidant. On

Carol's request, he had earlier asked the Guard's leader to consider an

alliance with the king, which Codreanu promptly refused in favor of

negotiations with Goga, coupled with claims that he was not interested

in political battles (an attitude supposedly induced by Antonescu

himself).

Soon

afterward, Călinescu, acting on indications from the monarch, arrested

Codreanu and prosecuted him in two successive trials. Antonescu, whose

mandate of Defense Minister had been prolonged under the premiership of Miron Cristea, resigned in protest to Codreanu's arrest. He was a celebrity defense witness at the latter's first and second trials. During the latter, which saw Codreanu's conviction for treason, Antonescu vouched for his friend's honesty while shaking his hand in front of the jury. Upon the end of procedures, the king ordered his former minister interned at Predeal, before assigning him to command the Third Army in the remote eastern region of Bessarabia (and later removing him after Antonescu expressed sympathy for Guardists imprisoned in Chişinău). Attempting to discredit his rival, Carol also ordered Antonescu's wife to be tried for bigamy,

based on a false claim that her divorce had not been finalized.

Defended by Mihai Antonescu, the officer was able to prove his

detractors wrong. Codreanu himself was taken into custody and discreetly killed by the Gendarmes acting on Carol's orders (November 1938). Carol's regime slowly dissolved into crisis, the process being enhanced after the start of World War II, when the military success of the core Axis Powers and the non-aggression pact signed by Germany and the Soviet Union saw Romania isolated and threatened. In 1940, two of Romania's regions, Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, were lost to a Soviet occupation consented to by the king. This came as Romania, exposed by the Fall of France, was seeking to align its policies with those of Germany. Ion Antonescu himself had come to value a pro-Axis alternative after the 1938 Munich Agreement, when Germany imposed demands on Czechoslovakia with the acquiescence of France and the United Kingdom, leaving locals to fear that, unless reoriented, Romania would follow. Angered

by the territorial losses of 1940, General Antonescu sent Carol a

general note of protest, and, as a result, was arrested and interned at Bistriţa Monastery. While

there, he commissioned Mihai Antonescu to establish contacts with Nazi

German officials, promising to advance German economic interest,

particularly in respect to the local oil industry, in exchange for endorsement. Commenting on Ion Antonescu's ambivalent stance, Hitler's Ambassador to Romania, Wilhelm Fabricius, wrote to his superiors: "I am not convinced that he is a safe man." His internment ended in August, during which interval, under Axis pressure, Romania had ceded Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria (Treaty of Craiova) and Northern Transylvania to Hungary (Second Vienna Award).

The latter grant caused consternation among large sections of Romania's

population, causing Carol's popularity to fall to a record low and

provoking large-scale protests in Bucharest, the capital. These

movements were organized competitively by the pro-Allied PNŢ, headed by Iuliu Maniu, and the pro-Nazi Iron Guard. The latter group had been revived under the leadership of Horia Sima, and was organizing a coup d'état. In

this troubled context, Antonescu simply left his assigned residence. He

may have been secretly helped in this by German intercession, but was more directly aided to escape by socialite Alice Sturdza, who was acting on Maniu's request. Antonescu subsequently met with Maniu in Ploieşti, where they discussed how best to manage the political situation. While

these negotiations were carried out, the monarch himself was being

advised by his entourage to recover legitimacy by governing in tandem

with the increasingly popular Antonescu, while creating a new political

majority from the existing forces. Carol and Antonescu accepted the proposal, Antonescu being mandated to approach political party leaders Maniu of the PNŢ and Dinu Brătianu of the PNL. They all called for Carol's abdication as a preliminary measure, while Sima, another leader sought after for negotiations, could not be found in time to express his opinion. Antonescu partly complied with the request but also asked Carol to bestow upon him the reserve powers for Romanian heads of state. Carol yielded and, on September 5, 1940, the general became Prime Minister with full powers as head of state. The latter's first measure was to curtail potential resistance within the Army by relieving Bucharest Garrison chief Gheorghe Argeşanu of his position and replacing him with Dumitru Coroamă. Shortly afterward, Antonescu heard rumors that two of Carol's loyalist generals, Gheorghe Mihail and Paul Teodorescu, were planning to have him killed. In

reaction, he imposed formal abdication on the monarch, while General

Coroamă was refusing to carry out the royal order of shooting down Iron

Guardist protesters. The

king eventually left the throne and Michael I inaugurated his second

rule, while Antonescu's effective powers as dictatorial Premier were

confirmed and extended. He was formally declared Conducător of the state on September 6, by a royal decree which consecrated a ceremonial role for the monarch. Among his subsequent measures was ensuring the safe departure into self-exile of Carol and his mistress Elena Lupescu, granting protection to the royal train when it was attacked by armed members of the Iron Guard. Horia

Sima's subsequent cooperation with Antonescu was endorsed by

high-ranking Nazi German officials, many of whom feared the Iron Guard

was too weak to rule on its own. Antonescu therefore received the approval of Ambassador Fabricius. Despite early promises, Antonescu abandoned projects for the creation of a national government, and opted instead for a coalition between a military dictatorship lobby and the Iron Guard. He later justified his choice by stating that the Iron Guard "represented the political base of the country at the time." The resulting regime, deemed the National Legionary State and officially proclaimed on September 14, had Antonescu as Premier and Conducător, with Sima as Deputy Premier and leader of the Iron Guard, the latter being remodeled into a single official party. Antonescu subsequently ordered Carol's Iron Guardist prisoners to be set free. On

October 6, he presided over the Iron Guard's mass rally in Bucharest,

one in a series of major celebratory and commemorative events organized

by the movement during the late months of 1940. However, he tolerated the PNŢ and PNL's informal existence, allowing them to preserve much of their political support. There

followed a short-lived and always uneasy partnership between Antonescu

and Sima. In late September, the new regime denounced all pacts,

accords and diplomatic agreements signed under Carol, bringing the

country into Germany's orbit while subverting its relationship with a

former Balkan ally, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Germans troops entered the country in stages, in order to defend the local oil industry and help instruct their Romanian counterparts on Blitzkrieg tactics. On November 23, Antonescu was in Berlin, where his signature sealed Romania's commitment to the main Axis instrument, theTripartite Pact. Two days later, the country also adhered to the Nazi-led Anti-Comintern Pact. Other

than these generic commitments, Romania had no treaty binding it to

Germany, and the Romanian-German alliance functioned informally. Speaking

in 1946, Antonescu claimed to have followed the pro-German path in

continuation of earlier policies, and for fear of a Nazi protectorate in Romania. During the National Legionary State period, earlier antisemitic legislation was upheld and strengthened, while the "Romanianization" of Jewish-owned enterprises became standard official practice. Immediately after coming into office, Antonescu himself expanded the anti-Jewish and Nuremberg law-inspired legislation passed by his predecessors Goga and Ion Gigurtu, while tens of new anti-Jewish regulations were passed in 1941-1942. This was done despite his formal pledge to Wilhelm Filderman and the Jewish Communities Federation that, unless engaged in "sabotage", "the Jewish population will not suffer." Antonescu did not reject the application of Legionary policies, but was offended by Sima's advocacy of paramilitarism and the Guard's frequent recourse to street violence. He drew much hostility from his partners by extending some protection to former dignitaries whom the Iron Guard had arrested. One early incident opposed Antonescu to the Guard's magazine Buna Vestire, which accused him of leniency and was subsequently forced to change its editorial board. By

then, the Legionary press was routinely claiming that he was

obstructing revolution and aiming to take control of the Iron Guard,

and that he had been transformed into a tool of the Freemasonry. The

political conflict coincided with major social challenges, including

the influx of refugees from areas lost earlier in the year and a large-scale earthquake affecting Bucharest. Disorder

peaked in the last days of November 1940, when, after uncovering the

circumstances of Codreanu's death, the fascist movement ordered

retaliations against political figures previously associated with

Carol, carrying out the Jilava Massacre, the assassinations of Nicolae Iorga and Virgil Madgearu, and several other acts of violence. As retaliation for this insubordination, Antonescu ordered the Army to resume control of the streets, unsuccessfully pressured Sima to have the assassins detained, ousted the Iron Guardist prefect of Bucharest Police Ştefan Zăvoianu, and ordered Legionary ministers to swear an oath to the Conducător. His

condemnation of the killings was nevertheless limited and discreet,

and, the same month, he joined Sima at a burial ceremony for Codreanu's

newly-discovered remains. The widening gap between the dictator and Sima's party resonated in Berlin. When, in December, Legionary Foreign Minister Mihail R. Sturdza obtained the replacement of Fabricius with Manfred Freiherr von Killinger,

perceived as more sympathetic to the Iron Guard, Antonescu promptly

took over leadership of the ministry, with the compliant diplomat Constantin Greceanu as his right hand. In Germany, such leaders of the Nazi Party as Heinrich Himmler, Baldur von Schirach and Joseph Goebbels threw their support behind the Legionaries, whereas Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and the Wehrmacht stood by Antonescu. The latter group was concerned that any internal conflict would threaten Romania's oil industry, vital to the German war effort. The German leadership was by then secretly organizing Operation Barbarossa, the attack on the Soviet Union. Antonescu's plan to act against his coalition partners in the event of further disorder hinged on Hitler's approval, a vague signal of which had been given during ceremonies confirming Romania's adherence to the Tripartite Pact. A

decisive turn occurred when Hitler invited Antonescu and Sima both over

for discussions: whereas Antonescu agreed, Sima stayed behind in

Romania, probably plotting a coup d'état. While

Hitler did not produce a clear endorsement for clamping down on Sima's

party, he made remarks interpreted by their recipient as oblique

blessings. The

Antonescu-Sima dispute erupted into violence in January 1941, when the

Iron Guard instigated a series of attacks on public institutions and a pogrom, incidents collectively known as the "Legionary Rebellion". This

came after the mysterious assassination of Major Döring, a German

agent in Bucharest, which was used by the Iron Guard as a pretext to

accuse the Conducător of having a secret anti-German agenda, and made Antonescu oust the Legionary Interior Minister, Constantin Petrovicescu, while closing down all of the Legionary-controlled "Romanianization" offices. Various other clashes prompted him to demand the resignation of all Police commanders who sympathized with the movement. After two days of widespread violence, during which Guardists killed some 120 Bucharest Jews, Antonescu sent in the Army, under the command of General Constantin Sănătescu. German officials acting on Hitler's orders, including the new Ambassador Manfred Freiherr von Killinger,

helped Antonescu eliminate the Iron Guardists, but several of their

lower-level colleagues actively aided Sima's subordinates. Goebbels was especially upset by the decision to support Antonescu, believing it to have been advantageous to "the Freemasons". After the events, Hitler kept his options open by granting political asylum to Sima — whom Antonescu's courts sentenced to death — and to other Legionaries in similar situations. The Guardists were detained in special conditions at Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps. In parallel, Antonescu publicly obtained the cooperation of Codrenists, members of an Iron Guardist wing which had virulently opposed Sima, and whose leader was Codreanu's father Ion Zelea Codreanu. Antonescu again sought backing from the PNŢ and PNL to form a national cabinet, but his rejection of parliamentarism made the two groups refuse him. Antonescu traveled to Germany and met Hitler on eight more occasions between June 1941 and August 1944. Such

close contacts helped cement an enduring relationship between the two

dictators, and Hitler reportedly came to see Antonescu as the only

trustworthy person in Romania, and the only foreigner to consult on military matters. In later statements, he offered praise to Antonescu's "breadth of vision" and "real personality." The

German military presence increased significantly in early 1941, when,

using Romania as a base, Hitler invaded the rebellious Kingdom of

Yugoslavia and the Kingdom of Greece. In

parallel, Romania's relationship with the United Kingdom (at the time

the only major adversary of Nazi Germany) aggravated into conflict: on

February 10, 1941, British Premier Winston Churchill recalled His Majesty's Ambassador Reginald Hoare, and approved the blockade of Romanian ships in British-controlled ports. In June of that year, Romania joined the attack on the Soviet Union, led by Germany in coalition with Hungary, Finland, the State of Slovakia, the Kingdom of Italy and the Independent State of Croatia.

Antonescu had been made aware of the plan by German envoys, and

supported it enthusiastically even before Hitler extended Romania an

offer to participate. The Romanian force engaged formed a General Antonescu Army Group under the effective command of German general Eugen Ritter von Schobert. Romania's campaign on the Eastern Front began without a formal declaration of war, and was consecrated by Antonescu's statement: "Soldiers, I order you, cross the Prut River" (in reference to the Bessarabian border between Romania and post-1940 Soviet territory). A few days after this, a large-scale pogrom was carried out in Iaşi with Antonescu's agreement; thousands of Jews were killed. After becoming the first Romanian to be granted the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, which he received from Hitler at their August 6 meeting in the Ukrainian city of Berdychiv, Ion Antonescu was promoted to Marshal of Romania by royal decree on August 22, in recognition for his role in restoring the eastern frontiers of Greater Romania. He

took one of his most debated decisions when, with Bessarabia's conquest

almost complete, he committed Romania to Hitler's war effort beyond the Dniester —

that is, beyond territory that had been part of Romania between the

wars — and thrust deeper into Soviet territory, thus waging a war of aggression. On August 30, Romania occupied a territory it deemed "Transnistria", formerly a part of the Ukrainian SSR (including the entire Moldavian ASSR and further territories). Like

the decision to continue the war beyond Bessarabia, this earned

Antonescu much criticism from the semi-clandestine PNL and PNŢ. Soon after the takeover, the area was assigned to a civil administration apparatus headed by Gheorghe Alexianu and became the site for the main component of the Holocaust in Romania: a mass deportation of the Bessarabian and Ukrainian Jews, followed later by transports of Romani Romanians and

Jews from Moldavia proper (that is, the portions of Moldavia west of

the Prut). The accord over Transnistria's administration, signed in Tighina, also placed areas between the Dniester and the Dnieper under Romanian military occupation, while granting control over all resources to Germany. The

Romanian Army's inferior arms, insufficient armor and lack of training

had been major concerns for the German commanders since before the

start of the operation. One of the earliest major obstacles Antonescu encountered on the Eastern Front was the resistance of Odessa, a Soviet port on the Black Sea. Refusing any German assistance, he ordered the Romanian Army to maintain a two-month siege on heavily-fortified and well-defended positions. The ill-equipped 4th Army suffered losses of some 100,000 people. Antonescu's

popularity again rose in October, when the fall of Odessa was

celebrated triumphantly with a parade through Bucharest's Arcul de Triumf, and when many Romanians reportedly believed the war was as good as won. In Odessa itself, the aftermath included a large-scale massacre of

the Jewish population, ordered by the Marshal as retaliation for a

bombing which killed a number of Romanian officers and soldiers (General Ioan Glogojeanu among them). The city subsequently became the administrative capital of Transnistria. According to one account, the Romanian administration planned to change Odessa's name to Antonescu. As the Soviet Union recovered from the initial shock and slowed down the Axis offensive at the Battle of Moscow (October 1941-January 1942), Romania was asked by its allies to contribute a larger number of troops. A

decisive factor in Antonescu's compliance with the request appears to

have been a special visit to Bucharest by Wehrmacht commander Wilhelm Keitel, who introduced the Conducător to Hitler's plan for attacking the Caucasus. The Romanian force engaged in the war reportedly exceeded German demands. It came to around 500,000 people and thirty actively-involved divisions. As a sign of his satisfaction, Hitler presented his Romanian counterpart with a luxury car. On

December 7, 1941, after reflecting on the possibility for Romania,

Hungary and Finland to change their stance, the British government

responded to repeated Soviet requests and declared war on all three

countries. Following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and in compliance with its Axis commitment, Romania declared war on the United States within

five days. These developments contrasted with Antonescu's own statement

of December 7: "I am an ally of the [German] Reich against [the Soviet

Union], I am neutral in the conflict between Great Britain and Germany.

I am for America against the Japanese." A crucial change in the war came with the Battle of Stalingrad in June 1942-February 1943, a major defeat for the Axis. Romania's armies alone lost some 150,000 men (either dead, wounded or captured) and more than half of the country's divisions were wiped out. For

part of that interval, the Marshal had withdrawn from public life,

owing to an unknown affliction, which is variously rumored to have been

a mental breakdown, a foodborne illness or a symptom of the syphilis he had allegedly contracted earlier in life. He is known to have been suffering from digestive problems, treating himself with food prepared by Marlene von Exner, an Austrian-born dietitian who moved into Hitler's service after 1943. Upon his return, Antonescu blamed the Romanian losses on German overseer Arthur Hauffe, whom Hitler agreed to replace. In parallel with the military losses, Romania was confronted with large-scale economic problems. While Germany monopolized Romania's exports, it defaulted on most of its payments. Like to all countries whose exports to Germany, particularly in oil, exceeded imports from that country, Romania's economy suffered from Nazi control of the exchange rate. On the German side, those directly involved in harnessing Romania's economic output for German goals were economic planners Hermann Göring and Walther Funk, together with Hermann Neubacher, the Special Representative for Economic Problems. The situation was further aggravated in 1942, as USAAF and RAF were able to bomb the oil fields in Prahova County (Operation Tidal Wave). Official

sources from the following period amalgamate military and civilian

losses of all kinds, which produces a total of 554,000 victims of the

war. In

this context, the Romanian leader acknowledged that Germany was losing

the war, and he therefore authorized his Deputy Premier and new Foreign

Minister Mihai Antonescu to set up contacts with the Allies. In

parallel, he allowed the PNŢ and the PNL to engage in parallel talks

with the Allies at various locations in neutral countries. The discussions were strained by the Western Allies' call for an unconditional surrender, over which the Romanian envoys bargained with Allied diplomats in Sweden and Egypt (among them the Soviet representatives Nikolai Vasilevich Novikov and Alexandra Kollontai). Antonescu was also alarmed by the possibility of war being carried on Romanian territory, as had happened in Italy after Operation Avalanche. The

events also prompted hostile negotiations aimed at toppling Antonescu,

and involving the two political parties, the young monarch, diplomats

and soldiers. A

major clash between Michael and Antonescu took place during the first

days of 1943, when the 21-year old monarch used his New Year's address

on national radio to part with the Axis war effort. In March 1944, the Soviet Red Army broke the Southern Bug and Dniester fronts, advancing on Bessarabia. This came just as Henry Maitland Wilson, Allied commander of the Mediterranean theater, presented Antonescu with an ultimatum. After

a new visit to Germany and a meeting with Hitler, Antonescu opted to

continue fighting alongside the remaining Axis states, a decision which

he later claimed was motivated by Hitler's promise to allow Romania

possession of Northern Transylvania in the event of an Axis victory. Upon his return, the Conducător oversaw a counteroffensive which stabilized the front on a line between Iaşi and Chişinău to the north and the lower Dniester to the east. This normalized his relations with Nazi German officials, whose alarm over the possible loss of an ally had resulted in the Margarethe II plan, an adapted version of the Nazi takeover in Hungary. However,

Antonescu's non-compliance with the terms of Wilson's ultimatum also

had drastic effects on Romania's ability to exit the war. By then, Antonescu was conceiving of a separate peace with the Western Allies, while maintaining contacts with the Soviets. In parallel, the mainstream opposition movement came to establish contacts with the Romanian Communist Party (PCR), which, although minor numerically, gained importance for being the only political group to be favored by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. On the PCR side, the discussions involved Lucreţiu Pătrăşcanu and later Emil Bodnăraş. Another participating group at this stage was the old Romanian Social Democratic Party. Large-scale Allied bombings of Bucharest took place in spring 1944, while the Soviet Red Army approached Romanian borders. The Battle for Romania began in late summer: while German commanders Johannes Frießner and Otto Wöhler of the Army Group South Ukraine attempted to hold Bukovina, Soviet Steppe Front leader Rodion Malinovsky stormed into the areas of Moldavia defended by Petre Dumitrescu's troops. In reaction, Antonescu attempted to stabilize the front on a line between Focşani, Nămoloasa and Brăila, deep inside Romanian territory. On August 5, he visited Hitler one final time in Kętrzyn.

On this occasion, the German leader reportedly explained that his

people had betrayed the Nazi cause, and asked him if Romania would go

on fighting (to which Antonescu reportedly answered in vague terms). After Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov more than once stated that the Soviet Union was not going to require Romanian subservience, the factions opposing Antonescu agreed that the moment had come to overthrow him, by carrying out the Royal Coup of August 23. On that day, the sovereign asked Antonescu to meet him in the royal palace building, where he presented him with a request to take Romania out of its Axis alliance. The Conducător refused, and was promptly arrested by soldiers of the guard, being replaced as Premier with General Constantin Sănătescu, who presided over a national government. The new Romanian authorities declared peace with the Allies and advised the population to greet Soviet troops. On August 25, as Bucharest was successfully defending itself against German retaliations, Romania declared war on Nazi Germany. The events disrupted German domination in the Balkans, putting a stop to the Maibaum offensive against Yugoslav Partisans. The coup was nevertheless a unilateral move, and, until the signature of an armistice on September 12, the country was still perceived as an enemy by the Soviets, who continued to take Romanian soldiers as prisoners of war. In parallel, Hitler reactivated the Iron Guardist exile, creating a Sima-led government in exile that did not survive the war's end in Europe. Placed in the custody of PCR militants, Ion Antonescu spent the interval at a house in Bucharest's Vatra Luminoasă quarter. He was afterward handed to the Soviet occupation forces, who transported him to Moscow, together with his deputy Mihai Antonescu, Governor of Transnistria Gheorghe Alexianu, Defense Minister Constantin Pantazi, Gendarmerie commander Constantin Vasiliu and Bucharest Police chief Mircea Elefterescu. They were subsequently kept in luxurious detention at a mansion nearby the city, and guarded by SMERSH, a special counter-intelligence body answering directly to Stalin. Shortly after Germany surrendered in May 1945, the group was moved to Lubyanka prison. There, Antonescu was interrogated and reputedly pressured by SMERSH operatives, among them Viktor Semyonovich Abakumov, but transcripts of their conversations were never sent back to Romania by the Soviet authorities. Later

research noted that the main issues discussed were the German-Romanian

alliance, the war on the Soviet Union, the economic toll on both

countries, and Romania's participation in the Holocaust (defined specifically as crimes against "peaceful Soviet citizens"). At some point during this period, Antonescu attempted suicide in his quarters. He was returned to Bucharest in spring 1946 and held in Jilava prison. He was subsequently interrogated by prosecutor Avram Bunaciu,

to whom he complained about the conditions of his detainment,

contrasting them with those in Moscow, while explaining that he was a vegetarian and demanding a special diet. In May 1946, Ion Antonescu was prosecuted at the first in a series of People's Tribunals, on charges of war crimes, crimes against the peace and treason. The tribunals had first been proposed by the PNŢ, and was compatible with the Nuremberg Trials in Allied-occupied Germany. The

Romanian legislative framework was drafted by coup participant

Pătrăşcanu, a PCR member who had been granted leadership of the Justice Ministry. Despite

the idea having earned support from several sides of the political

spectrum, the procedures were politicized in a sense favorable to the

PCR and the Soviet Union, and posed a legal problem for being based on ex post facto decisions. The first such local trial took place in 1945, resulting in the sentencing of Iosif Iacobici, Nicolae Macici, Constantin Trestioreanu and other military commanders directly involved in planning or carrying out the Odessa massacre. Antonescu was represented by Constantin Paraschivescu-Bălăceanu and Titus Stoica, two public defenders whom he had first consulted with a day before the procedures were initiated. The prosecution team, led by Vasile Stoican, and the panel of judges, presided over by Alexandru Voitinovici, were infiltrated by PCR supporters. Both

consistently failed to admit that Antonescu's foreign policies were

overall dictated by Romania's positioning between Germany and the

Soviet Union. Nevertheless,

and although references to the mass murders formed just 23% of the

indictment and corpus of evidence (ranking below charges of anti-Soviet

aggression), the

procedures also included Antonescu's admission of and self-exculpating

take on war crimes, including the deportations to Transnistria. They

also evidence his awareness of the Odessa massacre, accompanied by his

claim that few of the deaths were his direct responsibility. One notable event at the trial was a testimony by PNŢ leader Iuliu Maniu.

Reacting against the aggressive tone of other accusers, Maniu went on

record saying: "We [Maniu and Antonescu] were political adversaries, not cannibals." Upon leaving the bench, Maniu walked toward Antonescu and shook his hand. Ion Antonescu was found guilty of the charges. This verdict was followed by two sets of appeals, which claimed that the restored and amended 1923 Constitution did not offer a framework for the People's Tribunals and prevented capital punishment during peacetime, while noting that, contrary to the armistice agreement, only one power represented within the Allied Commission had supervised the tribunal. They

were both rejected within six days, in compliance with a legal deadline

on the completion of trials by the People's Tribunals. King Michael subsequently received pleas for clemency from

Antonescu's lawyer and his mother, and reputedly considered asking the

Allies to reassess the case as part of the actual Nuremberg Trials,

taking Romanian war criminals into foreign custody. Subjected to pressures by the new Soviet-backed Petru Groza executive, he issued a decree in favor of execution. Together with his co-defendants Mihai Antonescu, Alexianu and Vasiliu, the former Conducător was executed by a military firing squad on

June 1, 1946. Ion Antonescu's supporters circulated false rumors that

regular soldiers had refused to fire at their commander, and that the

squad was mostly composed of Jewish policemen. Another apologetic claim insists that he himself ordered the squad to shoot, but footage of the event has proven it false. It is however attested that he refused a blindfold and raised his hat in salute once the order was given. The execution site, some distance away from the locality of Jilava and the prison fort, was known as Valea Piersicilor ("Valley of the Peach Trees"). His final written statement was a letter to his wife, urging her to withdraw into a convent, while stating the belief that posterity would reconsider his deeds and accusing Romanians of being "ungrateful".